ABC's Summary Report 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Helping You Find the Right Community and Social Services. Joint Message from The

211 ANNUAL REPORT 2014 ANNUAL REPORT 2014 Helping you find the right community and social services. Joint Message from the Chair and Executive Director The 2014 calendar year was the first full year of Twitter have tripled. operation for 211, following launch of the service on February11, 2013, and it has been a year of Calendar 2014 has also been a year of strategic growth. Monthly average call volumes as well as partnerships. In late 2013, 211NS launched visits to the 211 website (www.ns.211.ca) have an awareness campaign directed at “caring increased by 30% over the previous year. This growth professionals” including clergy, social workers, is the result of expanding awareness throughout emergency responders, health care and educational Nova Scotia, which continues to be a priority for professionals. We are very pleased to report our team. This priority was reflected in the hiring of that several “caring professional” organizations a full time Community Relations Officer in January have joined the campaign. The College of Family 2014, dedicated to promotion of 211 through Physicians of Nova Scotia promoted 211 in April communications and outreach. through a directed mail out to more than 1,100 family physicians. Fire Officer and paramedic associations Organizations across Nova Scotia continue to included 211 on the agenda of annual conferences demonstrate strong support for 211. In 2014, our and in December, the Association of Chiefs of Police team responded to more than 100 requests for announced that 211 would be promoted as part of presentations. We are grateful to the many service the tool kit provided to all Police Officers in Nova providers who have helped spread the word about Scotia. -

Dartmouth Assessment of Street Involved Population Using an Evidence-Based Framework

Dartmouth Assessment of street involved population using an evidence-based framework October 2018 Objective What are the needs of the street involved population in Dartmouth? Does Dartmouth need a shelter/crisis centre? This research has been initiated to apply an evidence- based rationale for addressing the needs of street involved populations in the community of Dartmouth, Nova Scotia Produced by: Affordable Housing Association of Nova Scotia Claudia Jahn- Program Director David Harrison, MCIP-Researcher Charlene Gagnon- Researcher Methodology A framework for moving forward • Literature review • Statistical Data Scan • Stakeholder interviews • Homeless Surveys Literature Review Harm Reduction in Dartmouth North: The Highfield/Pinecrest Neighbourhood planning for addiction, April 2018 Housing Initiative: A Working Proposal, September 2016 Housing Trilogy, Dartmouth North Report, November 2017 Click here to access analysis and report including tables. “Report #3: Summary of Dartmouth North Studies” Statistics Data review and analysis A review and analysis of available, relevant data was conducted. Report #1 provides information on housing and income variables for the federal riding of Dartmouth-Cole Harbour. Statistics Canada 2016 census information was used to create a profile of housing and income factors for Dartmouth-Cole Harbour. Data sub-sets were generated to help highlight geographical areas and populations at- risk of homelessness; and other determinants, for example, housing and income factors that may have a bearing on affordable housing. Best efforts were made to compile data at the Provincial riding level. Click here to access analysis and report including tables. “Report #1: Housing and Income Indicators” All three levels of government are increasingly involved in addressing affordable housing and homelessness. -

Electoral District of Dartmouth North

Map 1 of 1 18 - Electoral District of Dartmouth North ank eaver B ver-B ll Ri -Fa ley er av - W 54 17 - Dartmouth East k n a B r e v a e -B r e iv Highway118 R ll a -F y le r 04 - Bedforde Basin n v te a x W - ls E 4 il 5 H t s e r o F h t t r s o a N E h t h t u u o o m t m r t r a a D - D - 8 1 7 1 lvd ey B Akerl Lake Charles C u tl er A ve d lv B y e rl e k A 1 7 44 - Preston - D W a G r lo i t ria l Mc k m c Juniper Lake i lu n o s s u k o t ey n h A A E a ve v e s t Colford Ave M e ng o n i A Simmonds Dr ve Jim C onnors Ave e St v e A rn s y Crt G e uil n g i d Payzant Ave f H o r d A v e Topple Dr Frazee Ave Jennett Ave 8 Akerley Blvd 1 1 W y e a s e t v w o h n g C e A i Vidito Dr g rt H d i Dorey Ave r b Williams Ave r u Burnside Dr B J o Troop Ave s e p h Pettipas Dr Z a tz m r e a r D v n e A Ca D n 038 r bela r e r l R u t d T Gurholt Dr u C rt g C s Mosher Dr in re J C o tt er o rid Dartmouth h T r F N n yne L t Wright Ave D n r S C a y Mellor Ave e v a rf a l a n g i c W Countryview Dr e r S F ig Isnor Dr ht A Ave v e Kiltearn Row Shubie Dr M or ri entu w s V re o D Gloster Crt Ave r R land R u ar s G i n Moore Rd ul Fielding Ave o FerindonaldF Close d lv B y le r e L k og A Borden Ave ie al mo Raddall Ave nd Cl Wright Ave ose Mc Windmill Rd Clu th re Clo or se N r h t D 04 - Bedfordo uBasin tm w B r e u i Spectacle Da Dawn Dr rle - v rt Lake 18 y C Cromarty Dr n M i C c o Hector Gate s c m a u r m B dy o d 1 A S o 1 pec r 7 v B ta Ralston Ave e cle e 8 L D - u a D r k r - n e a D Ilsley Ave s D r a i t d r Cuddy Ln r m e -

October 8, 2013 Nova Scotia Provincial General

47.1° N 59.2° W Cape Dauphin Point Aconi Sackville-Beaver Bank Middle Sackville Windsor μ Alder Junction Point Sackville-Cobequid Waverley Bay St. Lawrence Lower Meat Cove Capstick Sackville Florence Bras d'Or Waverley- North Preston New Waterford Hammonds Plains- Fall River- Lake Echo Aspy Bay Sydney Mines Dingwall Lucasville Beaver Bank Lingan Cape North Dartmouth White Point South Harbour Bedford East Cape Breton Centre Red River Big Intervale Hammonds Plains Cape North Preston-Dartmouth Pleasant Bay Bedford North Neils Harbour Sydney Preston Gardiner Mines Glace Bay Dartmouth North South Bar Glace Bay Burnside Donkin Ingonish Minesville Reserve Mines Ingonish Beach Petit Étang Ingonish Chéticamp Ferry Upper Marconi Lawrencetown La Pointe Northside- Towers Belle-Marche Clayton Cole Point Cross Victoria-The Lakes Westmount Whitney Pier Park Dartmouth Harbour- Halifax Sydney- Grand Lake Road Grand Étang Wreck Cove St. Joseph Leitches Creek du Moine West Portland Valley Eastern Shore Whitney Timberlea Needham Westmount French River Fairview- Port Morien Cap Le Moine Dartmouth Pier Cole Balls Creek Birch Grove Clayton Harbour Breton Cove South Sydney Belle Côte Kingross Park Halifax ^ Halifax Margaree Harbour North Shore Portree Chebucto Margaree Chimney Corner Beechville Halifax Citadel- Indian Brook Margaree Valley Tarbotvale Margaree Centre See CBRM Inset Halifax Armdale Cole Harbour-Eastern Passage St. Rose River Bennet Cape Dauphin Sable Island Point Aconi Cow Bay Sydney River Mira Road Sydney River-Mira-Louisbourg Margaree Forks Egypt Road North River BridgeJersey Cove Homeville Alder Point North East Margaree Dunvegan Englishtown Big Bras d'Or Florence Quarry St. Anns Eastern Passage South West Margaree Broad Cove Sydney New Waterford Bras d'Or Chapel MacLeods Point Mines Lingan Timberlea-Prospect Gold Brook St. -

Hansard 18-46 Debates And

HANSARD 18-46 DEBATES AND PROCEEDINGS Speaker: Honourable Kevin Murphy Published by Order of the Legislature by Hansard Reporting Services and printed by the Queen's Printer. Available on INTERNET at http://nslegislature.ca/index.php/proceedings/hansard/ First Session FRIDAY, APRIL 6, 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE GOVERNMENT NOTICES OF MOTION: Res. 1157, House of Assembly: Members’ Attendance and Leaves of Absence, Hon. K. Regan ...................................................................3705 Vote - Affirmative..................................................................................3706 Res. 1158, World Health Day: Com. Health - Advance, Hon. R. Delorey .................................................................................................3706 Vote - Affirmative..................................................................................3707 Res. 1159, NSISP: Providing Excellence, Hon. L. Diab ......................................................................................................3707 Vote - Affirmative..................................................................................3708 Res. 1160, Roy, Jane: Points of Light Award - Congrats., Hon. L. Glavine..................................................................................................3708 Vote - Affirmative..................................................................................3709 Res. 1161, Tartan Day: Scottish Gaelic Heritage - Recognize, Hon. R. Delorey .................................................................................................3709 -

Capital Plan 2022 TABLE of CONTENTS

2021 Capital Plan 2022 TABLE OF CONTENTS CAPITAL PROJECT INDEX CAPITAL PLAN OVERVIEW……………………………………………….. A 2021/22 CAPITAL PLAN - PROJECT DETAIL SHEETS: BUILDINGS/FACILITIES……………………………………………… B BUSINESS SYSTEMS…………………………………………………. C OUTDOOR RECREATION…………………………………………….. D Outdoor Sports Facilities Parks ROADS, ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION & BRIDGES………………… E Bridges Roads & Active Transportation TRAFFIC & STREETLIGHTS…………………………………………. F Streetlights Traffic Signs/ Signalization/ Equipment VEHICLES, VESSELS & EQUIPMENT………………………………. G Equipment & Machinery Vehicles Vessels OTHER ASSETS………………………………………………………. H Art & Cultural Assets Landfill Assets Natural Assets Varied Assets Stormwater / Wastewater Assets Capital Project Index Project Name Budget Category Page # Access & Privacy Project Business Systems C1 Access-A-Bus Fueling Solution - BTC Buildings/Facilities B1 Access-A-Bus Replacement Vehicles, Vessels & Equipment G10 Accessibility - HRM Facilities Buildings/Facilities B2 Active Transportation - Strategic Projects Roads, Active Transportation & Bridges E3 Alderney Gate Library Renos Buildings/Facilities B3 Alderney Gate Recapitalization Buildings/Facilities B4 Application Recapitalization Business Systems C2 Bedford Library Replacement Buildings/Facilities B5 Bedford Outdoor Pool Outdoor Recreation D1 Bedford West Road Oversizing Roads, Active Transportation & Bridges E6 Beechville Lakeside Timberlea Recreation Centre Recap Buildings/Facilities B6 BMO Centre Buildings/Facilities B7 Bridges Roads, Active Transportation & Bridges E1 Building -

Seniors', Councils, Clubs, Centres and Other Seniors' Organizations

Provincial Directory of Seniors’, Councils, Clubs, Centres and Other Seniors’ Organizations 2010 EDITION Produced by the Nova Scotia Department of Seniors Directory of Senior Citizens’ Councils, Clubs, Centres, and Organizations 2010 Edition The Nova Scotia Department of Seniors publishes this directory to promote networking among seniors’ organizations in Nova Scotia and to help seniors find local recreational and community service opportunities of interest to them. We thank the many senior volunteers from across the province who kindly provided their information to us this year. Thank you also for your active participation in seniors-related organizations that enrich your community and promote Positive Aging among your fellow seniors. For more information on programs and services for seniors, contact the Nova Scotia Department of Seniors. Phone: (902) 424-0065 (HRM) 1-800-670-0065 (Toll-Free) Fax: (902) 424-0561 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.gov.ns.ca/seniors Attention: SENIORS’ CLUBS AND COUNCILS New members and ideas are vital to maintaining an active organization. Help us help new members find you by updating your contact information each year! Please send any changes to this information to the President of your local Seniors Council by August 1, 2010 for the Winter 2011 edition. Thank you! Please check the county/city where you would like to have your club/council listed in this directory: Annapolis Hants Antigonish & Guysborough Inverness & Victoria Cape Breton Kings Colchester/East Hants Lunenburg Cumberland Pictou Dartmouth Queens Digby Richmond Halifax City Shelburne Halifax County Yarmouth Club/Council: Name: Mailing Address: President: Name: Mailing Address: Phone: Secretary: Name: Phone Number: Treasurer: Name: Phone Number: RETURN TO: The President of your local Seniors’ Council NS Department of Seniors: Directory of Senior Citizens’ Councils, Clubs, Centres, and Organizations 2010 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS SENIORS’ COUNCILS AND CLUBS ANNAPOLIS COUNTY .................................................. -

Report #3 Factors Influencing Poverty and Homelessness in Dartmouth

Report #3 Factors Influencing Poverty and Homelessness in Dartmouth-Cole Harbour Summary of Dartmouth North Studies (Attached Tables for Dartmouth South and Dartmouth East) 1. Harm Reduction in Dartmouth North: planning for addiction 2. Housing Trilogy, Dartmouth North Report, November 2017 3. The Highfield/Pinecrest Neighbourhood Housing Initiative: A Working Proposal, September 2016 • PDF attachment, Dartmouth South and Dartmouth East 1. Harm Reduction in Dartmouth North: planning for addiction Juniper Littlefield Undergraduate Honours Thesis Proposal Advised by Ren Thomas April 9th, 2018 Bachelors of Community Design, Honours Urban Design Dalhousie University School of Planning Halifax, NS Dartmouth North stands out as having no focused mental health or addictions supports available to everyone. There are no public health locations in the area, and only one private practitioner—resulting in poor health care access. Drug-related charges (accessed through police records) and community consultation (Between the Bridges, 2015), indicate that alcohol, cocaine, and opiate dependencies are likely major concerns for the Dartmouth North community. Cannabis related charges are also frequent through each of these neighbourhoods, which based on literature, may indicate the presence of other mental health and addiction issues (Rhodes et al., 2006). Dartmouth North, located just inside the circumferential highway (Figure 1), has some of the lowest incomes and shelter costs in the Halifax Regional Municipality (HRM). 43% of households spend 30% or more of their income on shelter, signaling income-induced housing poverty (Statistics Canada, 2011). At 33.6%, this area has the highest neighbourhood rate of individual poverty in HRM, according to 2015 data included in United Way’s Poverty Solutions report (2018). -

Electoral History for Dartmouth North Electoral History for Dartmouth North

Electoral History for Dartmouth North Electoral History for Dartmouth North Including Former Electoral District Names Report Created for Nova Scotia Legislature Website by the Nova Scotia Legislative Library The returns as presented here are not official. Every effort has been made to make these results as accurate as possible. Return information was compiled from official electoral return reports and from newspapers of the day. The number of votes is listed as 0 if there is no information or the candidate won by acclamation. September 1, 2021 Page 1 of 31 Electoral History for Dartmouth North Dartmouth North In 1966, Halifax County-Dartmouth was divided into ten electoral districts including Dartmouth City North and Dartmouth City South. The "City" was removed from the district names in 1967 (SNS 1967, c. 46, s. 2). In 2003, minor changes were made to Dartmouth North's northern boundary and it gained the area on its southern boundary along Lake Banook from Dartmouth South (SNS 2002, c. 34). Member Elected Election Date Party Elected Leblanc, Susan 17-Aug-2021 New Democratic Party Majority: (1370) Candidate Party Votes Leblanc, Susan New Democratic Party 3731 Cooley, Pam Liberal 2361 Coates, Lisa Progressive Conservative 1278 Marshall, Carolyn Green Party 129 Leblanc, Susan 30-May-2017 New Democratic Party Majority: (329) Candidate Party Votes Leblanc, Susan New Democratic Party 2771 Bernard, Joanne Liberal 2442 Russell, Melanie L. Progressive Conservative 1384 Colbourne, Tyler J. Green Party 318 Boyd, David F. Atlantica 126 Bernard, Joanne 08-Oct-2013 Liberal Majority: (933) Candidate Party Votes Bernard, Joanne Liberal 2953 Estey, Steve New Democratic Party 2020 Brownlow, Séan G. -

Community Health Teams Provides Space Free of Charge to Community Groups to Offer Their Programs and Services for the Public

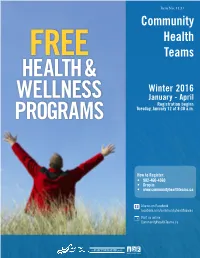

Item No. 11.3.1 Community Health FREE Teams HEALTH & Winter 2016 WELLNESS January - April Registration begins PROGRAMS Tuesday, January 12 at 8:30 a.m. HowTo Registercall to Register: 902-460-4560 • 902-460-4560 • Drop in • www.communityhealthteams.ca Like us on Facebook facebook.com/communityhealthteams Visit us online CommunityHealthTeams.ca WHAT IS A COMMUNITY HEALTH TEAM? A Community Health Team offers free wellness programs and services in your community. The range of programs and services offered by each Community Health Team are shaped by what we have heard citizens needed to best support their health. Your local Community Health Team: • Offers free group wellness programs at different times and community locations to make it easier for you to access sessions close to home. • Offers free wellness navigation to help you prioritize health goals and connect to the resources that you need. • Works closely together with community organizations toward building a stronger and healthier community. Meet friendly people and get healthier together at your Community Health Team! Bedford/Sackville Dartmouth Community Health Team (CHT) Community Health Team (CHT) 833 Sackville Drive (upper level), Lower Sackville 58 Tacoma Drive, Dartmouth Serving the Communities of Beaver Bank, Fall River, Serving the Communities of Dartmouth, Cole Hammonds Plains, Sackville, and Waverley. Harbour, Eastern Passage, Lawrencetown, Mineville, North and East Preston. Chebucto Halifax Peninsula Community Health Team (CHT) Community Health Team (CHT) 16 Dentith Road, Halifax Suite 105 6080 Young Street, Halifax Serving the Communities of Spryfield, Fairview, Serving the Communities of Downtown, North End, Clayton Park, Herring Cove, Armdale, Sambro Loop, South End, and West End Halifax. -

A Federal Brief on Dartmouth North

A Federal Brief on Dartmouth North A Community of Neighbourhoods Prepared for Human Resources and Skills Development Canada By United Way of Halifax Region March 28th, 2008 Compiled by Paul Shakotko, United Way of Halifax Region and Dennis Pilkey of Pilkey Consulting Table of Contents Introduction......................................................................................................................... 1 Statistical Profile................................................................................................................. 2 Demographics ................................................................................................................. 2 Employment.................................................................................................................... 3 Income............................................................................................................................. 3 Ownership.......................................................................................................................4 Education ........................................................................................................................ 4 Crime............................................................................................................................... 5 Voter Participation.......................................................................................................... 6 Community Facilities..................................................................................................... -

Community Health Teams

Community Health Teams FREE HEALTH & WELLNESS PROGRAMS 902-460-4560 How to Register: • 902-460-4560 September 2017- • Drop in • www.communityhealthteams.ca February 2018 VisitTo usRegistercall online 902-460-4560 CommunityHealthTeams.ca Register now facebook.com/communityhealthteams @CHTs_NSHA WHAT IS A COMMUNITY HEALTH TEAM? A Community Health Team offers free wellness programs and services in your community. The range of programs and services offered by each Community Health Team are shaped by what we have heard citizens need to best support their health. Your local Community Health Team: • Offers free group wellness programs at different times and community locations to make it easier for you to access sessions close to home. • Offers free wellness navigation to help you prioritize health goals and connect to the resources that you need. • Works closely together with community organizations toward building a stronger and healthier community. Meet friendly people and get healthier together at your local Community Health Team Bedford / Sackville Chebucto (Halifax Mainland) Community Health Team (CHT) Community Health Team (CHT) 833 Sackville Drive (upper level), Lower Sackville 16 Dentith Road, Halifax Until December 5, 2017 Serving the communities of Spryfield, Fairview, Clayton Park, Bedfiord Place Mall, 1658 Bedford Highway, Herring Cove, Armdale, Sambro Loop, the Pennants, Purcell’s Bedford - Effective December 8, 2017 Cove, Tantallon, Hubbards, St.Margaret’s Bay, Beechville, Serving the communities of Beaver Bank, Bedford, Fall River, Lakeside, Timberlea, Prospect, Hatchet Lake, and Hubley. Hammonds Plains, Sackville, and Waverley. Dartmouth Halifax Peninsula Community Health Team (CHT) Community Health Team (CHT) 58 Tacoma Drive, Dartmouth Suite 105 6080 Young Street, Halifax Serving the communities of Dartmouth, Cole Harbour, Eastern Serving the communities of downtown, north end, south end, Passage, Lawrencetown, Mineville, North and East Preston.