Ginger Baker's Jazz Confusion Hits Right Note at Cathedral Quarter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tenor Saxophone Mouthpiece When

MAY 2014 U.K. £3.50 DOWNBEAT.COM MAY 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 5 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editors Ed Enright Kathleen Costanza Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Ara Tirado Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, -

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers NMAH.AC.0584 Reuben Jackson and Wendy Shay 2015 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Music Manuscripts and Sheet Music, 1919 - 1973................................... 5 Series 2: Photographs, 1939-1990........................................................................ 21 Series 3: Scripts, 1957-1981.................................................................................. 64 Series 4: Correspondence, 1960-1996................................................................. -

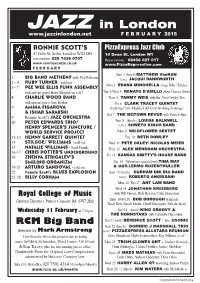

JAZZ in London F E B R U a R Y 2015

JAZZ in London www.jazzinlondon.net F E B R U A R Y 2015 RONNIE SCOTT’S PizzaExpress Jazz Club 47 Frith St. Soho, London W1D 4HT 10 Dean St. London W1 reservations: 020 7439 0747 Reservations: 08456 027 017 www.ronniescotts.co.uk www.PizzaExpresslive.com F E B R U A R Y Sun 1 (lunch) MATTHEW VanKAN with Phil Robson 1 BIG BAND METHENY (eve) JACQUI DANKWORTH 2 - 4 RUBY TURNER - sold out Mon 2 sings Billie Holiday 5 - 7 PEE WEE ELLIS FUNK ASSEMBLY EDANA MINGHELLA with special guest Huey Morgan on 6 & 7 Tue 3/Wed 4 RENATO D’AIELLO plays Horace Silver 8 CHARLIE WOOD BAND Thur 5 TAMMY WEIS with the Tom Cawley Trio with special guest Guy Barker Fri 6 CLARK TRACEY QUINTET 9 AMINA FIGAROVA featuring Chris Maddock & Henry Armburg-Jennings & ISHAR SARABSKI Sat 7 THE MOTOWN REVUE with Patrick Alan 9 Ronnie Scott’s JAZZ ORCHESTRA 10 PETER EDWARDS TRIO/ Sun 8 (lunch) LOUISE BALKWILL (eve) HENRY SPENCER’S JUNCTURE / SOWETO KINCH BAND WORLD SERVICE PROJECT Mon 9 WILDFLOWER SEXTET 11- 13 KENNY GARRETT QUINTET Tue 10 BETH ROWLEY 14 STILGOE/ WILLIAMS - sold out Wed 11 PETE OXLEY/ NICOLAS MEIER 15 - Soul Family NATALIE WILLIAMS Thur 12 ALEX MENDHAM ORCHESTRA 16-17 CHRIS POTTER’S UNDERGROUND Fri 13 18 ZHENYA STRIGALEV’S KANSAS SMITTY’S HOUSE BAND SMILING ORGANIZM Sat 14 Valentine’s special with TINA MAY 19-21 ARTURO SANDOVAL - sold out & GUILLERMO ROZENTHULLER 22 Ronnie Scott’s BLUES EXPLOSION Sun 15 (lunch) DURHAM UNI BIG BAND 23-28 BILLY COBHAM (eve) ROBERTO ANGRISANI Mon 16/ Tue17 ANT LAW BAND Wed 18 JONATHAN KREISBERG Royal College of Music with Will Vinson, Rick Rosato, Colin Stranahan (Britten Theatre) Prince Consort Rd. -

Music Outside? the Making of the British Jazz Avant-Garde 1968-1973

Banks, M. and Toynbee, J. (2014) Race, consecration and the music outside? The making of the British jazz avant-garde 1968-1973. In: Toynbee, J., Tackley, C. and Doffman, M. (eds.) Black British Jazz. Ashgate: Farnham, pp. 91-110. ISBN 9781472417565 There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/222646/ Deposited on 28 August 2020 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Race, Consecration and the ‘Music Outside’? The making of the British Jazz Avant-Garde: 1968-1973 Introduction: Making British Jazz ... and Race In 1968 the Arts Council of Great Britain (ACGB), the quasi-governmental agency responsible for providing public support for the arts, formed its first ‘Jazz Sub-Committee’. Its main business was to allocate bursaries usually consisting of no more than a few hundred pounds to jazz composers and musicians. The principal stipulation was that awards be used to develop creative activity that might not otherwise attract commercial support. Bassist, composer and bandleader Graham Collier was the first recipient – he received £500 to support his work on what became the Workpoints composition. In the early years of the scheme, further beneficiaries included Ian Carr, Mike Gibbs, Tony Oxley, Keith Tippett, Mike Taylor, Evan Parker and Mike Westbrook – all prominent members of what was seen as a new, emergent and distinctively British avant-garde jazz scene. Our point of departure in this chapter is that what might otherwise be regarded as a bureaucratic footnote in the annals of the ACGB was actually a crucial moment in the history of British jazz. -

Bourdieu and the Music Field

Bourdieu and the Music Field Professor Michael Grenfell This work as an example of the: Problem of Aesthetics A Reflective and Relational Methodology ‘to construct systems of intelligible relations capable of making sense of sentient data’. Rules of Art: p.xvi A reflexive understanding of the expressive impulse in trans-historical fields and the necessity of human creativity immanent in them. (ibid). A Bourdieusian Methodology for the Sub-Field of Musical Production • The process is always iterative … so this paper presents a ‘work in progress’ … • The presentation represents the state of play in a third cycle through data collection and analysis …so findings are contingent and diagrams used are the current working diagrams! • The process begins with the most prominent agents in the field since these are the ones with the most capital and the best configuration. A Bourdieusian Approach to the Music Field ……..involves……… Structure Structuring and Structured Structures Externalisation of Internality and the Internalisation of Externality => ‘A science of dialectical relations between objective structures…and the subjective dispositions within which these structures are actualised and which tend to reproduce them’. Bourdieu’s Thinking Tools “Habitus and Field designate bundles of relations. A field consists of a set of objective, historical relations between positions anchored in certain forms of power (or capital); habitus consists of a set of historical relations ‘deposited’ within individual bodies in the forms of mental and corporeal -

Varsity Jazz

Varsity Jazz Jazz at Reading University 1951 - 1984 By Trevor Bannister 1 VARSITY JAZZ Jazz at Reading University 1951 represented an important year for Reading University and for Reading’s local jazz scene. The appearance of Humphrey Lyttelton’s Band at the University Rag Ball, held at the Town Hall on 28th February, marked the first time a true product of the Revivalist jazz movement had played in the town. That it should be the Lyttelton band, Britain’s pre-eminent group of the time, led by the ex-Etonian and Grenadier Guardsman, Humphrey Lyttelton, made the event doubly important. Barely three days later, on 3rd March, the University Rag Committee presented a second event at the Town Hall. The Jazz Jamboree featured the Magnolia Jazz Band led by another trumpeter fast making a name for himself, the colourful Mick Mulligan. It would be the first of his many visits to Reading. Denny Dyson provided the vocals and the Yew Tree Jazz Band were on hand for interval support. There is no further mention of jazz activity at the university in the pages of the Reading Standard until 1956, when the clarinettist Sid Phillips led his acclaimed touring and broadcasting band on stage at the Town Hall for the Rag Ball on 25th February, supported by Len Lacy and His Sweet Band. Considering the intense animosity between the respective followers of traditional and modern jazz, which sometimes reached venomous extremes, the Rag Committee took a brave decision in 1958 to book exponents of the opposing schools. The Rag Ball at the Olympia Ballroom on 20th February, saw Ken Colyer’s Jazz Band, which followed the zealous path of its leader in keeping rigidly to the disciplines of New Orleans jazz, sharing the stage with the much cooler and sophisticated sounds of a quartet led by Tommy Whittle, a tenor saxophonist noted for his work with the Ted Heath Orchestra. -

Ebook Download Ginger Baker: Hellraiser

GINGER BAKER: HELLRAISER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Ginger Baker | 291 pages | 14 Mar 2012 | John Blake Publishing Ltd | 9781844549665 | English | London, United Kingdom Ginger Baker: Hellraiser PDF Book The price of the artwork will be in force from the date of publication on the website. Eventually, Liz had enough of her cheating husband Want to Read Currently Reading Read. His post-Cream catalogue includes about 25 titles. John Blake Publishing Ltd. Two years later they teamed with Mr. The Smiths. Even if it wasn't that great of a book Apparently, when he saw a fan being roughly manhandled off stage, Baker got up from his drums and assaulted a police officer. Little Richard. Well, Ginger Baker. Duke University Press. Louis Armstrong. Peter "Ginger" Baker is a legend. He used Ludwig Drums until the late s. Dan Baldwin. Retrieved 18 August I have always said, much to the amusement of some of my musically inclined friends, that Ginger Baker is the greatest rock drummer ever. Baker joined Blues Incorporated , one of the earliest British rhythm-and-blues bands, beginning his contentious but musically rewarding association with Mr. There are no discussion topics on this book yet. I've been a big fan of Ginger Baker's for years. All were born in the s during Mr. In the s, he came up with a trans-Saharan trucking scheme, was a successful rally driver, built an ill-fated recording studio, and discovered a consuming passion for playing polo. This review has been hidden because it contains spoilers. Suddenly it came to an abrupt halt which was met with a barely contained resignation from the mixing desk. -

January 1988

VOLUME 12, NUMBER 1, ISSUE 99 Cover Photo by Lissa Wales Wales PHIL GOULD Lissa In addition to drumming with Level 42, Phil Gould also is a by songwriter and lyricist for the group, which helps him fit his drums into the total picture. Photo by Simon Goodwin 16 RICHIE MORALES After paying years of dues with such artists as Herbie Mann, Ray Barretto, Gato Barbieri, and the Brecker Bros., Richie Morales is getting wide exposure with Spyro Gyra. by Jeff Potter 22 CHICK WEBB Although he died at the age of 33, Chick Webb had a lasting impact on jazz drumming, and was idolized by such notables as Gene Krupa and Buddy Rich. by Burt Korall 26 PERSONAL RELATIONSHIPS The many demands of a music career can interfere with a marriage or relationship. We spoke to several couples, including Steve and Susan Smith, Rod and Michele Morgenstein, and Tris and Celia Imboden, to find out what makes their relationships work. by Robyn Flans 30 MD TRIVIA CONTEST Win a Yamaha drumkit. 36 EDUCATION DRIVER'S SEAT by Rick Mattingly, Bob Saydlowski, Jr., and Rick Van Horn IN THE STUDIO Matching Drum Sounds To Big Band 122 Studio-Ready Drums Figures by Ed Shaughnessy 100 ELECTRONIC REVIEW by Craig Krampf 38 Dynacord P-20 Digital MIDI Drumkit TRACKING ROCK CHARTS by Bob Saydlowski, Jr. 126 Beware Of The Simple Drum Chart Steve Smith: "Lovin", Touchin', by Hank Jaramillo 42 Squeezin' " NEW AND NOTABLE 132 JAZZ DRUMMERS' WORKSHOP by Michael Lawson 102 PROFILES Meeting A Piece Of Music For The TIMP TALK First Time Dialogue For Timpani And Drumset FROM THE PAST by Peter Erskine 60 by Vic Firth 104 England's Phil Seamen THE MACHINE SHOP by Simon Goodwin 44 The Funk Machine SOUTH OF THE BORDER by Clive Brooks 66 The Merengue PORTRAITS 108 ROCK 'N' JAZZ CLINIC by John Santos Portinho A Little Can Go Long Way CONCEPTS by Carl Stormer 68 by Rod Morgenstein 80 Confidence 116 NEWS by Roy Burns LISTENER'S GUIDE UPDATE 6 Buddy Rich CLUB SCENE INDUSTRY HAPPENINGS 128 by Mark Gauthier 82 Periodic Checkups 118 MASTER CLASS by Rick Van Horn REVIEWS Portraits In Rhythm: Etude #10 ON TAPE 62 by Anthony J. -

Cream Cream Mp3, Flac, Wma

Cream Cream mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Cream Country: Europe Released: 2014 Style: Blues Rock, Psychedelic Rock, Hard Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1263 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1766 mb WMA version RAR size: 1937 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 189 Other Formats: TTA AHX MOD APE VOC MP3 MIDI Tracklist Hide Credits Fresh Cream N.S.U. A1 Written-By – Bruce* Sleepy Time Time A2 Written-By – Bruce*, Godfrey* Dreaming A3 Written-By – Bruce* Sweet Wine A4 Written-By – Baker*, Godfrey* Spoonful A5 Written-By – Willie Dixon Cat's Squirrel B1 Arranged By – S. SplurgeWritten-By – Trad.* Four Until Late B2 Written-By – Robert Johnson Rollin' And Tumblin' B3 Written-By – Muddy Waters I'm So Glad B4 Written-By – Skip James Toad B5 Written-By – Baker* Disraeli Gears Strange Brew C1 Written-By – Clapton*, Pappalardi*, Collins* Sunshine Of Your Love C2 Written-By – Clapton*, Bruce*, Brown* World Of Pain C3 Written-By – Pappalardi*, Collins* Dance The Night Away C4 Written-By – Bruce*, Brown* Blue Condition C5 Written-By – Baker* Tales Of Brave Ulysses D1 Written-By – Clapton*, Sharp* Swlabr D2 Written-By – Bruce*, Brown* We're Going Wrong D3 Written-By – Bruce* Outside Woman Blues D4 Written-By – Clapton* Take It Back D5 Written-By – Bruce*, Brown* Mother's Lament D6 Arranged By – Clapton*, Baker*, Bruce*Written-By – Trad.* Wheels Of Fire Disc 1 In The Studio White Room E1 Timpani [Tympani] – Ginger BakerViola – Felix PappalardiWritten-By – Jack 4:56 Bruce, Pete Brown Sitting On Top Of The World E2 4:56 Written-By – Chester Burnett -

HR: in His Recent Interview with Blackmoon Magazine, Jack Bruce Told Us That One of His Favourite Performances Had Been at Rockpalast with Rory Gallagher

HR: In his recent interview with Blackmoon Magazine, Jack Bruce told us that one of his favourite performances had been at RockPalast with Rory Gallagher. What are your own memories of sharing the stage with Rory? Gerry McAvoy : I remember the night Jack Bruce got up and jammed with Rory at Rockpalast. Jack had done his own show before us (solo on piano). It was fantastic, just to listen to that voice was amazing. I don't know if it was pre-planned, but when we finished our performance and as we were about to go back on stage for an encore, Rory asked Jack (who was standing side stage) would he like to get up for a jam. Jack said yes, and asked me if I would mind if he used my bass rig. Here's Jack Bruce, my idol since I was a teenager asking to use my amp. I mean, what do you say? So they jammed "Politician" a Cream number, It was fantastic! As for my own memories of sharing the stage with Rory. It was fantastic 90% of the time. Like any band you do have off nights. But they were few and far between. It was a pleasure to work with a man with so much talent. Ted McKenna : Always on the edge. Never sure of what might happen next. Always pushing to give 150% for the whole 2hr - 2.30min show. That's the way Rory played. It was real and raw with all the rough edges. I'd call it Rock'n'Roll! Hearing from Gerry there about Jack Bruce, it reminded me that I'd had the great pleasure of working with Jack some years ago myself. -

Concerts Thursday 17Th November

C0NCERTS Thursday 17th November Royal Conservatoire of Scotland (RCS) Glasgow Friday 18th November The Blue Lamp, Aberdeen Concerts Thursday 17th November, Royal Conservatoire of Scotland (RCS) Glasgow Friday 18th November, The Blue Lamp, Aberdeen WELCOME TO TONIGHT’S CONCERT BY THE 2016 EURORADIO JAZZ ORCHESTRA It is a great honour to be hosting the 2016 Euroradio Jazz Orchestra. We are particularly thrilled that Tommy Smith, Scotland’s most prominent jazz artist and a leading and prolific educator is such an integral part of this project. The Euroradio Jazz Orchestra is a unique initiative which supports jazz at the highest level. Each player here tonight has been nominated to represent their country by their national broadcaster. We hope that they will enjoy both a profound musical experience and also make lasting friendships as they build on their professional careers. The concert at RCS Glasgow on 17th November will be recorded, and made available for broadcast by EBU radio organizations from 25th November onwards. It will be broadcast on Radio 3’s Jazz Line Up on the10th December 2016. Highlights will also feature on Radio Scotland’s Jazz House. And finally, we are delighted to introduce Alexandra Ridout, the reigning BBC Young Musician of the Year - Jazz Award to our colleagues in Europe to perform Kenny Wheeler’s solo part in the Sweet Sister Suite. Enjoy a unique moment in jazz history tonight! Lindsay Pell Senior Producer, Music BBC Scotland | BBC Radio 3 BBC Broadcasting House 40 Pacific Quay Glasgow G51 1DA Email: [email protected] -

Music Newsletter

St. Faith’s Church Choir NEWSLETTER FRIDAY 3RD JULY 2020 Welcome to another edition of ramblings from the organist! Congratulations on making it through June… and welcome to July! Here is this week’s newsletter… as ever, comments, feedback, suggestions welcome! All about Hymns Live streamed services Richard McVeigh continues his (some personal recommendations) live request show of hymns and Last Sunday, quite a few places celebrated organ music every Sunday the feast of St. Peter and St. Paul evening starting at 5pm via his “Beauty in (transferred from Monday 29th). Sound” YouTube channel. Members of the choir of https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCkdRX Chingford Parish Church (NE ZZXDmLJM6XBnUpIoog/videos London) recorded a hymn with You might be interested to see and hear words about St. Peter: how far Richard gets playing “For all the https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iVlZYSwoUEI saints” using just one hand and one foot: Winchester Cathedral enjoyed https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lKrJjOZHaPY getting the thurible out for the The RSCM are continuing occasion and they dared to use a to offer a “hymn for the recording of the choir singing “For all the day” via their YouTube channel: saints” to a different tune. I have to say that the tune they used is an excellent one https://www.youtube.com/user/RSCMCentre/videos by Stanford and, I think, fits the text New for this week, but better than the tune by Vaughan Williams. probably has been going for See what you think! some time, I found a really https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mq7GiwoHLIQ good “hymn of the week” resource on the website of Chelmsford Cathedral.