Postcolonial Automobility: West Africa and the Road to Globalization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No. 14 LAGOS- 7Thmarch,1963 Vol. 50

Ed mG i fe a Giooh te No. 14 LAGOS- 7th March,1963 Vol. 50 ‘CONTENTS we. / Page . Page Movethents of Officers - 270-7 Disposal of Unclaimed Firearms i .. 283 Appointment of Acting Chief Justice of the : 3 " Treasury Statements Nos..3-5 . 284-8 : Federation of Nigeria .. 277- List of Registered Contractors—Building, Probate Notice : 278 CivilEngineering and Electrical * 289-319 Delegation of Powers Notice, 1963 .. .. 279 List of Registered Chemists and Druggists 320-29 Grantof PioneerCertificate .. | 279 Paim Oil and Palm Kernels Purchasesiin the Federation of Nigeria 329 Appointment of Parliamentary Secretary 279 Awards for Undergraduate Studies and . Ministry of Communications Notices +279 Technical Training, 1963 .. .. 329-31 Loss ofLocal Purchase Orders,etc. 279-81 University of Nigeria—Applications for ss Admission 1963-4 . 331 Cancellation of Certificate of Registration of Trade Unions. 281 Tenders . tees . «. 332-3 Licensed Commercial Banks’ Analysisof . “Vacancies «» 333-9 Loans and Advances . 281 UNESCO Vacancies .. oe «awe 83339 Lagos Consumer Price Index—Lower Income Group - -. 281 -3 Board of Customs and Excise Sales Notices 339-40 Lagos Consumer Price Index—Middle . ' Application to operate ScheduledAir Services Income Group* . 282 340 ~ ‘Training of Nigerians as Commercial Pilots 282 Inpex To Lecan Notices n SUPPLEMENT ‘Teachers’ Grade III Certificate Examination, . 1956—-Supplementary Pass List -. 283 LN. No. Short Title Page Teachers’ Grade .II Certificate Examination, 983 - 27 Tin (Research tevy) Regulations, -1956—Supplementary Pass List — , : 1963 . os -- B73 270 (OFFICIAL ‘GAZETTE No. 14, Vol. 50 Guzernment Notice No, 429 + ~ NEW APPOINTMENTS AND OTHER STAFF CHANGES The following are notified for general information :— NEWAPPOINTMENTS Tv Depariment Name Appointment Date of Date of, Appointment Arrival Administration Adelaja, A. -

The Impact of Transportation Infrastructure on Nigeria's Economic Developmeny

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2016 The mpI act of Transportation Infrastructure on Nigeria's Economic Developmeny William A. Agbigbe Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons, Databases and Information Systems Commons, and the Management Sciences and Quantitative Methods Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Management and Technology This is to certify that the doctoral dissertation by William A. Agbigbe Sr. has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Robert DeYoung, Committee Chairperson, Management Faculty Dr. Godwin Igein, Committee Member, Management Faculty Dr. Salvatore Sinatra, University Reviewer, Management Faculty Chief Academic Officer Eric Riedel, Ph.D. Walden University 2016 Abstract The Impact of Transportation Infrastructure on Nigeria’s Economic Development by William A. Agbigbe, Sr. MA, Southern Illinois University, 1981 BSBA, University of Missouri, 1976 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Management Walden University August 2016 Abstract The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) described Nigeria’s road networks as one of the poorest and deadliest transportation infrastructural systems in the world. -

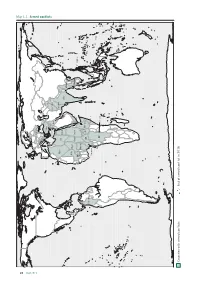

Armed Conflicts

Map 22 1 . 1. Armed conicts Ukraine Turkey Syria Palestine Afghanistan Iraq Israel Algeria Pakistan Libya Egypt India Myanmar Mali Niger Chad Sudan Thailand Yemen Burkina Philippines Faso Nigeria South Ethiopia CAR Sudan Colombia Somalia Cameroon DRC Burundi Countries with armed conflicts End2018 of armed conflict in Alert 2019 1. Armed conflicts • 34 armed conflicts were reported in 2018, 33 of them remained active at end of the year. Most of the conflicts occurred in Africa (16), followed by Asia (nine), the Middle East (six), Europe (two) and America (one). • The violence affecting Cameroon’s English-speaking majority regions since 2016 escalated during the year, becoming a war scenario with serious consequences for the civilian population. • In an atmosphere characterised by systematic ceasefire violations and the imposition of international sanctions, South Sudan reached a new peace agreement, though there was scepticism about its viability. • The increase and spread of violence in the CAR plunged it into the third most serious humanitarian crisis in the world, according to the United Nations. • The situation in Colombia deteriorated as a result of the fragility of the peace process and the finalisation of the ceasefire agreement between the government and the ELN guerrilla group. • High-intensity violence persisted in Afghanistan, but significant progress was made in the exploratory peace process. • The levels of violence in southern Thailand were the lowest since the conflict began in 2004. • There were less deaths linked to the conflict with the PKK in Turkey, but repression continued against Kurdish civilians and the risk of destabilisation grew due to the repercussions of the conflict in Syria. -

Role of Transportation and Marketing in Enhancing Agricultural Production in Ikwo Local Government Area of Ebonyi State, Nigeria

Sustainability, Agri, Food and Environmental Research, (ISSN: 0719-3726), 6(4), 2018: 22-39 22 http://dx.doi.org/10.7770/safer-V0N0-art1353 ROLE OF TRANSPORTATION AND MARKETING IN ENHANCING AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTION IN IKWO LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA OF EBONYI STATE, NIGERIA. ROL DEL TRANSPORTE Y MERCADO EN ESTIMULACIÓN DE LA PRODUCCIÓN AGRICOLA EN EL GOBIERNO LOCAL DEL AREA DEL ESTADO DE EBONYI, NIGERIA. Ume Smiles Ifeanyichukwu*, K.O. knadosie, C Kadurumba Agricultural Extension and Management.Federal College of Agriculture Ishiagu, Ebonyi State, Nigeria. Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Anambra State, Nigeria. * Corresponding Author; [email protected] ABSTRACT Role of transport and marketing in enhancing agricultural production in Ikwo Local Government Area of Ebonyi State, Nigeria was studied. A multi stage sampling procedure was used to select 300 respondents for the detailed study. A structured questionnaire was used to elicit information from the respondents. Data collected were analyzed using of chi-square. The results show that head carrying, use of wheel barrows, bicycles, motor van, keke, donkeys, and motor cycles were various traditional modes of transportation for inter local transport of agricultural products. Furthermore, the result reveals that producers, retailers, consumers, wholesalers and processors were the marketing channels in the study area. Additionally, transportation and marketing have greatly enhanced the growth of agricultural production in the study area, despite existing problems such as bad roads, high cost of transport, few vehicles, poor drainage channels, culverts, few bridges and poverty. Also, the solutions to the identified problems were giving out loans to farmers, construction and repairs of roads, use of rail, mass transit, encouraging farmers’ cooperative societies and processing centres. -

Dumb-Belling Her Way to Fame

Paje TWIG Dumb-belling Her Way to Fame The layingl of Suzanne, merry, ing.nuoUi and abounding in whimlical error, have become the talk of the Itudio, Experts in movie behaviorism and worldly willdom haven't been able to de- termine whether her malapropisms are genuine or feigned. She has "a lin.:' but whether it is native clevemell or congenital "dumbne.s" is an unsolved problem. ,......•••...... She couldn't make any sense out of (l dictionary because it wasn't written in complete sentences. way's mental capacity. For ex- Movie Veteran at 19 Years of Age ample, she was handed a dte- tionary and asked if she knew how to use it. She said: By GEORGE SHAFFER Bovard family, founders of th University of Southern Calif 01 "The book I've got at home Hollywood, Cal. nia here. makes sense, but this one isn't ALTHOUGH but 19, .Mary The actress's mother, Mr: even written in complete sen- Belch, former Blooming- I"l.. Hulda Belch, and her brothel tences." ton, Ill., girl, is already a Albert, 18, now make their hom She informed Director Prinz HoI Lyw 0 0 d "trouper." Her with Mary in Hollywood. He that she wanted to be an act- screen career began on a daring father resides in Chicago. Th ress instead of a dancer "be- chance When, three years ago, mother and brother moved rror cause actresses get to sit down the high school sophomore long their Bloomington home whe oftener." distanced Bob Palmer, RKO· Mary came west to take up he Radio studios' casting director, • • • movie career. -

The Third Wave of Historical Scholarship on Nigeria

CHAPTER ONE THE THIRD WAVE OF HISTORICAL SCHOLARSHIP ON NIGERIA SAHEED ADERINTO AND PAUL OSIFODUNRIN The significant place of Nigeria in Africanist studies is indisputable— it is one of the birthplaces of academic historical research on Africa. Nigeria is also one of the most studied countries in Africa.1 Academic writings on the country date back to the 1950s when scholars at the University College Ibadan (later the University of Ibadan) launched serious investigations into the nation’s precolonial and colonial past. The ideology of this first wave of academic history was well laid out—guarded and propagated from the 1950s through the 1970s. Scholars were convinced that research into the precolonial histories of state and empire formation and the sophistication of political structures before the advent of imperialism would supply the evidence needed to counteract the notion— obnoxious to Africans—that they needed external political overlords because of their inability to govern themselves. Historical research was therefore pivoted toward restoring Nigerian peoples into history. This brand of academic tradition, widely called “nationalist historiography,” supplied the much needed ideological tools for decolonization through its deployment of oral history, archaeology, and linguistic evidence. But like any school of thought, nationalist historiography had to adapt to new ideas and respond to changing events; unfortunately its failure to reshape its research agenda and inability to reinvent itself, coupled with several developments outside academia, made it an anachronism and set in motion its demise from the 1980s or earlier.2 However, the story of nationalist historiography transcends its “rise” and “fall.” Indeed, without nationalist historiography, historical research Copyright © 2012. -

The Impact of Transportation on Economic Development in Nigeria

International Journal of Contemporary Applied Researches Vol. 5, No. 8, August 2018 (ISSN: 2308-1365) www.ijcar.net THE IMPACT OF TRANSPORTATION ON ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN NIGERIA ADEYI EMMANUEL OLA (PhD) Department of Economics, Gombe State University, Gombe State, Nigeria Abstract The link between transport and economic development has been debated over many years, but we still lack a generally applicable and clear relationship which can be use universally. Despite this, there is a popular view that transport is not only necessary for economic growth and development to take place; it is the major instigator of such growth and development. Since the desire of every nation including Nigeria is the attainment of economic growth and development. This paper examines the linkage between transportation and economic development. It also examined the supply and demand for transport and then described the foundations of the possible linkage between transport and economic development from historical and contemporary perspectives. The study used both theoretical models as econometrics model as the data were soured from secondary sources to examine the impact of transportation on economic development. The paper observes that there is positive relationship between transportation and economic development. The study thereby recommends that there should be positive necessary market conditions as well as complementing and supportive policies well designed and enforced by the transport policymakers and government in addition to provision of necessary infrastructure facilities Keywords: Transportation, Economic Development, Labour productivity. Ordinary Least Square’ Transport supply and demand 140 International Journal of Contemporary Applied Researches Vol. 5, No. 8, August 2018 (ISSN: 2308-1365) www.ijcar.net 1.0 INTRODUCTION It is widely acknowledged that transport has crucial roles to play in economic development. -

Analysis of the Contributions of Transport Sectortoeconomic Growth in Nigeria

IOSR Journal of Economics and Finance (IOSR-JEF) e-ISSN: 2321-5933, p-ISSN: 2321-5925.Volume 11, Issue 6 Ser. III (Nov. –Dec. 2020), PP 18- 35www.iosrjournals.org ANALYSIS OF THE CONTRIBUTIONS OF TRANSPORT SECTORTOECONOMIC GROWTH IN NIGERIA *OCHEI, Monday Chi, **MAMUDU, Zebedee Udo *Department of Economics, Faculty of Social Sciences, Ambrose Alli University, Ekpoma, Edo State, Nigeria. **Department of Economics, Faculty of Social Sciences, Ambrose Alli University, Ekpoma, Edo State, Nigeria. Abstract This paper empirically examined the contributions of transport sectorto Economic Growth in Nigeriawith the application of the Phillips-Perron test statistics, Johansen Cointegration techniques, Pairwise Granger Causality techniques and the error correction mechanism on a multiple log linear regression framework.The annual time series data from 1981 to 2019 on economic growth(Real gross domestic product (RGDP) and transportation variables (Road transport (RDTP), Rail transport and pipelines (RLTP), Water transport (WRTP), Air transport (ARTP), Transport services (TPSS) and Post and courier services (PTCS)were sourced from Central Bank of Nigeria Statistical Bulletin (2019).The results of the Phillips-Perron test statistics showed that all the variables (RGDP, RDTP, RLTP, ARTP and PTCS) were stationary at first difference I(1) except WRTP and TPSS which were stationary at level I(0), while the Johansen unrestricted cointegration rank test results showed the existence of a unique long run relationship between RDTP, RLTP, WRTP, ARTP, TPSS and PTCS, as both Trace and Max-Eigen statistics revealed twocointegrating equations respectively. The short run error correction mechanism results showed that the entire explanatory economic and transportation variables in the estimation met their expected signs except WRTPand TPSS. -

(Railway) in Nigeria: Frameworks, Indicators, Method and Tools

Nigerian Journal of Technology (NIJOTECH) Vol. 39, No. 3, July 2020, pp. 665 – 679 Copyright© Faculty of Engineering, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Print ISSN: 0331-8443, Electronic ISSN: 2467-8821 www.nijotech.com http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/njt.v39i3.4 DELIVERING SUSTAINABLE TRANSPORT INFRASTRUCTURE PROJECTS (RAILWAY) IN NIGERIA: FRAMEWORKS, INDICATORS, METHOD AND TOOLS O. M. Oraegbune1,* and O. O. Ugwu2 1, DEPT OF CIVIL ENGINEERING, MODIBBO ADAMA UNIV. OF TECHNOLOGY, YOLA, ADAMAWA STATE, NIGERIA 2, DEPARTMENT OF CIVIL ENGINEERING, FEDERAL UNIVERSITY NDUFU-ALIKE IKWO, EBONYI STATE, NIGERIA Email addresses: 1 [email protected], 2 [email protected] ABSTRACT This study presented the issue of railway transportation infrastructure sustainability which involves multi-dimensional view of sustainability criteria such as economy, environment and society with the problem of non-systematic method of assessment in Nigeria. The aim of this study is to ascertain the extent of practice of sustainability in railway transportation infrastructure projects through the frame work, methods, tools and identify infrastructure sustainability priority indicators amongst stakeholders. In this research, weighted sum model technique in multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA), was used. This section formulates the mathematical model for computing the sustainability index (SI) using the Weighted Sum Model (WSM) which is structured in three steps. Also employed in the assessment is cognitive/reasoning map decision aid for infrastructure sustainability appraisal. This study also discussed the issue of key performance project indicators for transport infrastructure using sustainability appraisal in infrastructure projects (SUSAIP). Sustainability indicators are discoursed base on regional level(s), for example All-region represents cumulative results from the four regions. -

An Analysis of the Issues and Challenges of Transportation in Nigeria and Egypt

The Business and Management Review Volume 7 Number 2 February 2016 An analysis of the issues and challenges of transportation in Nigeria and Egypt Avanenge Faajir Department of Business Management, Faculty of Management Sciences Benue State University, Makurdi, Nigeria Zizi Hassan Zidan College of International Transport and Logistics Arab Academy for Science, Technologies and Maintenance Transport, Alexandria, Egypt Key Words Air, Transportation, Road Transportation, Rail Transportation, Water Transportation, Economy Abstract Understanding the development of transportation management in Nigeria and Egypt is crucial to the understanding of the challenges facing the industry. In Africa, the potentials for growth and development is quite promising. The expansion in external trade among most African countries such as Nigeria, Benin, Togo and Ghana including Egypt has resulted in increased demand for more effective transportation. The expansion of international trade in these regions has placed a lot of demand on the importance of the transportation industry. This paper attempts to analyze issues and challenges in the transportation industry in Nigeria and Egypt. This was achieved by the use of secondary data sources. Major issues analyzed were, lack of coherent air transportation, policy, weak management, obsolete facilities, insecurity, air crashes, bad roads due to lack of maintenance, non-functioning of railway systems, bad water transportation among others. The study recommended that drastic measures will be to employ a total approach to air, road, rail and water transportation planning and management if the desired objective of economic recovery is to be achieved. 1. Introduction Understanding the development of transportation management in Nigeria and Egypt is concise to the understanding of the challenges facing the transportation industry. -

Road Haulage Constraints in the Transportation of Petroleum Products in Northern Nigeria

IOSR Journal of Environmental Science, Toxicology and Food Technology (IOSR-JESTFT) e-ISSN: 2319-2402,p- ISSN: 2319-2399.Volume 8, Issue 3 Ver. 1 (April 2014), PP 01-08 www.iosrjournals.org Road Haulage Constraints in the Transportation of Petroleum Products in Northern Nigeria Thompson O. Obasanjo; Martina Francis; James J. Williams Department of Geography, Adamawa State University, Mubi, Adamawa State, Nigeria Department of Geography, Adamawa State University, Mubi, Adamawa State, Nigeria Department of Geography, College of Education Hong, Adamawa State, Nigeria. Abstract: In Nigeria, about 80% of petroleum movements are done on the road and there has been a steady growth in number of road tanker vehicles. This study examines road haulage constraints in the transportation of petroleum products. The study relied on primary data obtained through systematic administration of questionnaire to truck drivers at the point of waiting to load petroleum products in Kaduna Refinery. In all, 182 respondents were sampled. These problems were rank-ordered, the result of the study reveals that the major constraint confronting tanker drivers in conveying petroleum products to the selected locations is delay at police and military check points (mean= 1.72), followed by mechanical problems (mean=2.17), using K-W non parametric test. Furthermore, the correlation matrix of the trucking problem result reveals that five pairs of the constraints were significant with the strongest positive correlation being that of bad roads and delay in off- loading, r=0.81, p< 0.001. These results are fundamental for the prioritization of palliative measures to improve the constraints of road haulage of petroleum products in northern Nigeria. -

Week Commencing Mon 5Th June 2017

Week commencing Mon 5th June 2017 MONDAY 5 JUNE 2017 06:00 Death on the Set (1935) Henry Kendall drama. 07:20 The Rogues (S1, Ep4) 08:20 Orders Are Orders (1954) Tony Hancock comedy. 09:55 Accident (1967) drama Dirk Bogarde. 12:00 Whats Good For The Goose (1969) Norman Wisdom comedy. 14:00 All OverThe Town (1949) drama Norman Wooland. 15:45 Glimpses: War & Order (1940) factual. 16:00 Sea of Sand (1958) war John Gregson. 18:00 Freewheelers (S6, Ep10) 18:30 Patricia Dainton presents. 18:35 Tread Softly (1952) crime John Bentley. 20:05 A Place To Go (1964) Rita Tushingham. 21:50 Glimpses: Concord in Flight (1969) factual. 22:00 Double X (1992) crime Norman Wisdom. 00:00 Kansas City Confidential (1952) thriller Lee Van Cleef. 02:00 The Ring (1953) drama Rita Moreno. 03:40 The Big Game (1995) drama Gary Webster. 05:45 Glimpses: Furniture Craftsmen (1940) factual short. FRIDAY 9 JUNE 2017 06:00 Say It With Flowers (1934) musical drama Mary Clare. TUESDAY 6 JUNE 2017 07:20 The Rogues (S1, Ep8) 08:20 Somewhere On Leave (1943) 06:00 Flood Tide (1934) drama George Carney. 07:15 The Rogues comedy Frank Randle. 10:10 The Cowboy & the Lady (1938) drama (S1, Ep5) 08:15 Love In Pawn (1953) comedy Barbara Kelly. 09:50 Gary Cooper. 12:00 A Kid For Two Farthings (1955) fantasy Diana Glimpses: War & Order (1940) factual. 10:05 Velvet Touch (1948) thriller Dors. 13:45 Glimpses: War & Order (1940) factual. 14:00 I’ve Gotta Rosalind Russell.