The Riddles of the Rooms of 221B Baker Street an Exhibition of Materials from the Sherlock Holmes Collections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buses from Knightsbridge

Buses from Knightsbridge 23 414 24 Buses towardsfrom Westbourne Park BusKnightsbridge Garage towards Maida Hill towards Hampstead Heath Shirland Road/Chippenham Road from stops KH, KP From 15 June 2019 route 14 will be re-routed to run from stops KB, KD, KW between Putney Heath and Russell Square. For stops Warren towards Warren Street please change at Charing Cross Street 52 Warwick Avenue Road to route 24 towards Hampstead Heath. 14 towards Willesden Bus Garage for Little Venice from stop KB, KD, KW 24 from stops KE, KF Maida Vale 23 414 Clifton Gardens Russell 24 Square Goodge towards Westbourne Park Bus Garage towards Maida Hill 74 towards Hampstead HeathStreet 19 452 Shirland Road/Chippenham Road towards fromtowards stops Kensal KH, KPRise 414From 15 June 2019 route 14from will be stops re-routed KB, KD to, KW run from stops KB, KD, KW between Putney Heath and Russell Square. For stops Finsbury Park 22 TottenhamWarren Ladbroke Grove from stops KE, KF, KJ, KM towards Warren Street please change atBaker Charing Street Cross Street 52 Warwick Avenue Road to route 24 towards Hampsteadfor Madame Heath. Tussauds from 14 stops KJ, KM Court from stops for Little Venice Road towards Willesden Bus Garage fromRegent stop Street KB, KD, KW KJ, KM Maida Vale 14 24 from stops KE, KF Edgware Road MargaretRussell Street/ Square Goodge 19 23 52 452 Clifton Gardens Oxford Circus Westbourne Bishop’s 74 Street Tottenham 19 Portobello and 452 Grove Bridge Road Paddington Oxford British Court Roadtowards Golborne Market towards Kensal Rise 414 fromGloucester stops KB, KD Place, KW Circus Museum Finsbury Park Ladbroke Grove from stops KE23, KF, KJ, KM St. -

His Last Bow an Epilogue of Sherlock Holmes

His Last Bow An Epilogue of Sherlock Holmes Arthur Conan Doyle This text is provided to you “as-is” without any warranty. No warranties of any kind, expressed or implied, are made to you as to the text or any medium it may be on, including but not limited to warranties of merchantablity or fitness for a particular purpose. This text was formatted from various free ASCII and HTML variants. See http://sherlock-holm.esfor an electronic form of this text and additional information about it. This text comes from the collection’s version 3.1. t was nine o’clock at night upon the sec- Then one comes suddenly upon something very ond of August—the most terrible August hard, and you know that you have reached the in the history of the world. One might limit and must adapt yourself to the fact. They I have thought already that God’s curse have, for example, their insular conventions which hung heavy over a degenerate world, for there was simply must be observed.” an awesome hush and a feeling of vague expectancy “Meaning ‘good form’ and that sort of thing?” in the sultry and stagnant air. The sun had long Von Bork sighed as one who had suffered much. set, but one blood-red gash like an open wound lay low in the distant west. Above, the stars were shin- “Meaning British prejudice in all its queer man- ing brightly, and below, the lights of the shipping ifestations. As an example I may quote one of my glimmered in the bay. -

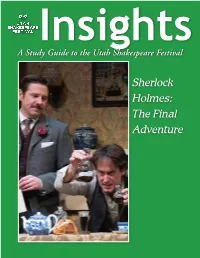

Sherlock Holmes: the Final Adventure the Articles in This Study Guide Are Not Meant to Mirror Or Interpret Any Productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival

Insights A Study Guide to the Utah Shakespeare Festival Sherlock Holmes: The Final Adventure The articles in this study guide are not meant to mirror or interpret any productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival. They are meant, instead, to be an educational jumping-off point to understanding and enjoying the plays (in any production at any theatre) a bit more thoroughly. Therefore the stories of the plays and the interpretative articles (and even characters, at times) may differ dramatically from what is ultimately produced on the Festival’s stages. The Study Guide is published by the Utah Shakespeare Festival, 351 West Center Street; Cedar City, UT 84720. Bruce C. Lee, communications director and editor; Phil Hermansen, art director. Copyright © 2014, Utah Shakespeare Festival. Please feel free to download and print The Study Guide, as long as you do not remove any identifying mark of the Utah Shakespeare Festival. For more information about Festival education programs: Utah Shakespeare Festival 351 West Center Street Cedar City, Utah 84720 435-586-7880 www.bard.org. Cover photo: Brian Vaughn (left) and J. Todd Adams in Sherlock Holmes: The Final Adventure, 2015. Contents Sherlock InformationHolmes: on the PlayThe Final Synopsis 4 Characters 5 About the AdventurePlaywright 6 Scholarly Articles on the Play The Final Adventures of Sherlock Holmes? 8 Utah Shakespeare Festival 3 351 West Center Street • Cedar City, Utah 84720 • 435-586-7880 Synopsis: Sherlock Holmes: The Final Adventure The play begins with the announcement of the death of Sherlock Holmes. It is 1891 London; and Dr. Watson, Holmes’s trusty colleague and loyal friend, tells the story of the famous detective’s last adventure. -

Star Wars at MT

NEW STAR WARS AT MADAME TUSSAUDS UNIQUE INTERACTIVE STAR WARS EXPERIENCE OPENS MAY 2015 A NEW multi-million pound experience opens at Madame Tussauds London in May, with a major new interactive Star Wars attraction. Created in close collaboration with Disney and Lucasfilm, the unique, immersive experience brings to life some of film’s most powerful moments featuring extraordinarily life- like wax figures in authentic walk-in sets. Fans can star alongside their favourite heroes and villains of Star Wars Episodes I-VI, with dynamic special effects and dramatic theming adding to the immersion as they encounter 16 characters in 11 separate sets. The attraction takes the Madame Tussauds experience to a whole new level with an experience that is about much more than the wax figures. Guests will become truly immersed in the films as they step right into Yoda's swamp as Luke Skywalker did in Star Wars: Episode V The Empire Strikes Back or feel the fiery lava of Mustafar as Anakin turns to the dark side in Star Wars: Episode III Revenge of the Sith. Spanning two floors, the experience covers a galaxy of locations from the swamps of Dagobah and Jabba’s Throne Room to the flight deck of the Millennium Falcon. Fans can come face-to-face with sinister Stormtroopers; witness Luke Skywalker as he battles Darth Vader on the Death Star; feel the Force alongside Obi-Wan Kenobi and Qui-Gon Jinn when they take on Darth Maul on Naboo; join the captive Princess Leia and the evil Jabba the Hutt in his Throne Room; and hang out with Han Solo in the cantina before stepping onto the Millennium Falcon with the legendary Wookiee warrior, Chewbacca. -

Mystery on Baker Street

MYSTERY ON BAKER STREET BRUTAL KAZAKH OFFICIAL LINKED TO £147M LONDON PROPERTY EMPIRE Big chunks of Baker Street are owned by a mysterious figure with close ties to a former Kazakh secret police chief accused of murder and money-laundering. JULY 2015 1 MYSTERY ON BAKER STREET Brutal Kazakh official linked to £147m London property empire EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The ability to hide and spend suspect cash overseas is a large part of what makes serious corruption and organised crime attractive. After all, it is difficult to stuff millions under a mattress. You need to be able to squirrel the money away in the international financial system, and then find somewhere nice to spend it. Increasingly, London’s high-end property market seems to be one of the go-to destinations to give questionable funds a veneer of respectability. It offers lawyers who sell secrecy for a living, banks who ask few questions, top private schools for your children and a glamorous lifestyle on your doorstep. Throw in easy access to anonymously-owned offshore companies to hide your identity and the source of your funds and it is easy to see why Rakhat Aliyev. (Credit: SHAMIL ZHUMATOV/X00499/Reuters/Corbis) London’s financial system is so attractive to those with something to hide. Global Witness’ investigations reveal numerous links This briefing uncovers a troubling example of how between Rakhat Aliyev, Nurali Aliyev, and high-end London can be used by anyone wanting to hide London property. The majority of this property their identity behind complex networks of companies surrounds one of the city’s most famous addresses, and properties. -

Case File #3: the BAKER STREET BUILDING

The Game is On! The Adventure of the Girl with the Light Blue Hair Deazley, R. (Author), Meletti, B. (Author), Bagni, M. (Designer), Bonazzi, D. (Author), ., S. (Composer), & McHugh, A. (Developer). (2015). The Game is On! The Adventure of the Girl with the Light Blue Hair. Digital or Visual Products, Coyright User. http://copyrightuser.org/the-game-is-on/episode-1/ Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2015 The Author This is an open access article published under a Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the author and source are cited. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:02. Oct. 2021 Case File #3: THE BAKER STREET BUILDING Sherlock Holmes and John Watson discuss Joseph’s case at 221B Baker Street. -

A Thematic Reading of Sherlock Holmes and His Adaptations

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2016 Crime and culture : a thematic reading of Sherlock Holmes and his adaptations. Britney Broyles University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Asian American Studies Commons, Chinese Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Television Commons Recommended Citation Broyles, Britney, "Crime and culture : a thematic reading of Sherlock Holmes and his adaptations." (2016). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2584. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2584 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CRIME AND CULTURE: A THEMATIC READING OF SHERLOCK HOLMES AND HIS ADAPTATIONS By Britney Broyles B.A., University of Louisville, 2008 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Comparative Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, KY December 2016 Copyright 2016 by Britney Broyles All rights reserved CRIME AND CULTURE: A THEMATIC READING OF SHERLOCK HOLMES AND HIS ADAPTATIONS By Britney Broyles B.A., University of Louisville, 2008 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 Dissertation Approved on November 22, 2016 by the following Dissertation Committee: Dr. -

His Last Bow Online

NPa3J (Mobile pdf) His Last Bow Online [NPa3J.ebook] His Last Bow Pdf Free Arthur Conan Doyle ebooks | Download PDF | *ePub | DOC | audiobook 2016-04-11 2016-04-11File Name: B01E4S1688 | File size: 33.Mb Arthur Conan Doyle : His Last Bow before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised His Last Bow: His Last Bow: Some Reminiscences of Sherlock Holmes is a collection of seven previously-published Sherlock Holmes stories by Arthur Conan Doyle. Five of the stories were published in The Strand Magazine between September 1908 and December 1913. The final story, an epilogue about Holmes' war service, was first published in Collier's on 22 September 1917mdash;one month before the book's premier on 22 October. Some later editions of the collection include "The Adventure of the Cardboard Box", which was also collected in The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes (1894). The Strand published "The Adventure of Wistaria Lodge" as "A Reminiscence of Sherlock Holmes", and divided it into two parts, called "The Singular Experience of Mr. John Scott Eccles" and "The Tiger of San Pedro". Later printings of His Last Bow correct Wistaria to Wisteria. Also, the first US edition adjusts the subtitle to Some Later Reminiscences of Sherlock Holmes. All editions contain a brief preface, by "John H. Watson, M.D.". The preface assures readers that as of the date of publication (1917), Holmes is long retired from his profession of detectivemdash;but is still alive and well, albeit suffering from a touch of rheumatism. -

His Last Bow

His Last Bow Arthur Conan Doyle Published: 1917 Categorie(s): Fiction, Mystery & Detective, Short Stories Source: Wikisource About Doyle: Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle, DL (22 May 1859 – 7 July 1930) was a Scottish author most noted for his stories about the detective Sherlock Holmes, which are generally considered a major innovation in the field of crime fiction, and the adventures of Professor Challenger. He was a prolific writer whose other works include science fiction stories, historical novels, plays and romances, poetry, and non-fiction. Conan was originally a given name, but Doyle used it as part of his surname in his later years. Source: Wikipedia Also available on Feedbooks Doyle: The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1892) The Casebook of Sherlock Holmes (1923) The Return of Sherlock Holmes (1905) The Hound of the Baskervilles (1902) The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes (1893) A Study in Scarlet (1887) The Sign of the Four (1890) The Lost World (1912) The Valley of Fear (1915) The Disintegration Machine (1928) Copyright: This work is available for countries where copyright is Life+70 and in the USA. Note: This book is brought to you by Feedbooks http://www.feedbooks.com Strictly for personal use, do not use this file for commercial purposes. Chapter 1 The Adventure of Wisteria Lodge 1. The Singular Experience of Mr. John Scott Eccles I find it recorded in my notebook that it was a bleak and windy day towards the end of March in the year 1892. Holmes had received a telegram while we sat at our lunch, and he had scribbled a reply. -

My Own 221B Baker Street ”To a Great Mind Nothing Is Little” (STUD)

My Own 221B Baker Street ”To a great mind nothing is little” (STUD) PLANNING AND BUILDING For forty years I had toyed with the idea of making myself a full-scale replica of the most famous room in the world literature, the legendary snug , unconventional sitting room at 221B Baker Street in London where most of the wonderful Sherlock Holmes adventures begin and where the reader, embedded in safe fellowship, listens to the detective revealing his remarkable clues to his dedicated friend Dr Watson while the eternal smoke from his pipe curles against the ceiling. However, on my own retirement we moved to a rather small terrace house and I had to drop the idea. I then suddenly remembered a fine letter from my friend John Bennett Shaw 1 where he temptingly describes the 221B miniature that his wife Dorothy had made for him, and realized that I could build my own scale model. Now, twelve years later, I can hardly think of anything more pleasant than a hobby including cultural and literary research, miniature handicraft and collecting. After having read the Holmes stories once again -- this time taking careful notes -- I started with a design draft. My proper scale would be the English 1:12, one inch to one foot. And my model should at least exibit the ground floor and the second floor of the famous three-storied Baker Street house. When musing about the dimensions of the house I decided on two criteria: The stairs leading up to the second floor must consist of seventeen steps2 and the sitting room had to be large enough to hold all the furniture that is mentioned in the stories3. -

Issue #53 Spring 2006

T HE NORWEGIAN EXPLORERS OF MINNESOTA, INC. ©2006 Winter, 2006 EXPLORATIONS Issue #53 EXPLORATIONSEXPLORATIONS From the (Outgoing) President . Julie McKuras, ASH, BSI Inside this issue: Internet Explorations 2 Annual Meeting & Dinner 3 Explorer Travels 4 A New Take on Mrs. Hudson 5 Holmes and Plastic Man? 6 The English 8 A Toast to Mycroft 9 Sherlock’s Last Case 9 From the Editor’s Desk Study Group 10 n this last issue of Explorations for 2006 delivered at our annual dinner, joining I we recap our recent annual meeting and frequent contributors Mike Eckman and dinner, notable for a changing of the guard Bob Brusic as well as Study Group reviewer as Julie McKuras stepped down after an Charles Clifford. Phil Bergem continues his energetic nine years as president of the Nor- Internet Explorations, and we look forward wegian Explorers. We are sure that our new to an upcoming performance of a Sher- president, Gary Thaden, will ably carry on lockian play. in the tradition of Julie and all our past Letters to the editor or other submis- leaders, including our founder and Siger- sions for Explorations are always welcome. son, the late E.W. “Mac” McDiarmid. We Please email items in Word or plain text also note travels by Explorers to two recent format to [email protected] conferences, both of which featured speak- ers from the ranks of the Explorers. We John Bergquist, BSI welcome Ray Riethmeier as a contributor to Editor, Explorations the newsletter by printing his fine toast Page 2 EXPLORATIONS Issue #53 From the (Incoming) President Internet Explorations . -

Elementary, My Dear Readers

NEW ORLEANS NOSTALGIA Remembering New Orleans History, Culture and Traditions By Ned Hémard Elementary, My Dear Readers NCIS (which stands for Naval Criminal Investigative Service) is an extremely popular “police procedural” television drama that has spun off as a New Orleans series. NCIS: New Orleans, which airs Tuesday nights on CBS, is set in the Crescent City and it would be highly unusual if you haven’t seen the show filming around town. It premiered on September 23, 2014. The episodes revolve around a fictional team of agents led by Special Agent Dwayne Cassius “King” Pride, Special Agent Christopher LaSalle, and Special Agent Meredith Brody. They handle criminal investigations involving the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps. If the NCIS team seems to be everywhere you look these days, allow yourself to travel back in literary time and imagine another famous detective team present all around you. Even if their bailiwick was late Victorian England, I seem to feel their presence all around this historic city. Perhaps you will, too. Arthur Conan Doyle penned his first Sherlock Holmes story, A Study in Scarlet, in novel form in 1886 at the age of 27. In it Holmes expounded: “Criminal cases are continually hinging upon that one point. A man is suspected of a crime months perhaps after it has been committed. His linen or clothes are examined and brownish stains discovered upon them. Are they blood stains, or mud stains, or rust stains, or fruit stains, or what are they? That is a question which has puzzled many an expert, and why? Because there was no reliable test.