From Parson to Professional: the Changing Ministry of the Anglican Clergy in Staffordshire, 1830-1960

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

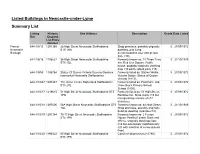

Listed Buildings in Newcastle-Under-Lyme Summary List

Listed Buildings in Newcastle-under-Lyme Summary List Listing Historic Site Address Description Grade Date Listed Ref. England List Entry Number Former 644-1/8/15 1291369 28 High Street Newcastle Staffordshire Shop premises, possibly originally II 27/09/1972 Newcastle ST5 1RA dwelling, with living Borough accommodation over and at rear (late c18). 644-1/8/16 1196521 36 High Street Newcastle Staffordshire Formerly known as: 14 Three Tuns II 21/10/1949 ST5 1QL Inn, Red Lion Square. Public house, probably originally dwelling (late c16 partly rebuilt early c19). 644-1/9/55 1196764 Statue Of Queen Victoria Queens Gardens Formerly listed as: Station Walks, II 27/09/1972 Ironmarket Newcastle Staffordshire Victoria Statue. Statue of Queen Victoria (1913). 644-1/10/47 1297487 The Orme Centre Higherland Staffordshire Formerly listed as: Pool Dam, Old II 27/09/1972 ST5 2TE Orme Boy's Primary School. School (1850). 644-1/10/17 1219615 51 High Street Newcastle Staffordshire ST5 Formerly listed as: 51 High Street, II 27/09/1972 1PN Rainbow Inn. Shop (early c19 but incorporating remains of c17 structure). 644-1/10/18 1297606 56A High Street Newcastle Staffordshire ST5 Formerly known as: 44 High Street. II 21/10/1949 1QL Shop premises, possibly originally build as dwelling (mid-late c18). 644-1/10/19 1291384 75-77 High Street Newcastle Staffordshire Formerly known as: 2 Fenton II 27/09/1972 ST5 1PN House, Penkhull street. Bank and offices, originally dwellings (late c18 but extensively modified early c20 with insertion of a new ground floor). 644-1/10/20 1196522 85 High Street Newcastle Staffordshire Commercial premises (c1790). -

The History of Blithfield Reservoir the History of Blithfield Reservoir

The History of Blithfield Reservoir The History of Blithfield Reservoir The land before Blithfield Reservoir Prior to the development of Blithfield Reservoir, the landscape consisted largely of fields with small areas of woodland, and was formed in the shape of a wide flat valley with a floor of alluvial sand and gravel; the land was used mainly by farmers for growing crops and grazing their animals. The River Blithe meandered for three miles through these woods and fields, with the small Kitty Fisher Brook winding alongside. The Tad Brook, slightly larger than the Kitty Fisher Brook, flowed into the north eastern part of the area. There were two buildings within the area that would eventually be flooded. In Yeatsall Hollow, at the foot of the valley, there was a small thatched cottage called Blithmoor Lodge. This was demolished to make way for the causeway that now allows vehicles to cross the Reservoir. The second building was an old mill called Blithfield Mill, positioned on the western bank of the River Blithe, and having an adjacent millpond; the mill’s water wheel was driven by the flowing water of the River Blithe. Although some maps show the mill as having been demolished, the foundation stones and the brick wall around the millpond remain. At times when the level of the Reservoir becomes low enough these remains become visible. During the 1930s and 1940s, The South Staffordshire Waterworks Company, as it was then known, purchased 952 hectares, (2,350 acres) of land, of which 642 hectares, (1,585 acres) was purchased from Lord Bagot. -

MAY 2014 Parish Assembly Minutes

BLYMHILL AND WESTON-UNDER-LIZARD ANNUAL PARISH ASSEMBLY MINUTES AT 7.30 PM ON MONDAY 12 MAY 2013. THE ANNUAL PARISH ASSEMBLY OF BLYMHILL AND WESTON-UNDER-LIZARD TOOK PLACE IN THE BLYMHILL AND WESTON-UNDER-LIZARD VILLAGE HALL. AGENDA 1 MINUTES OF PREVIOUS MEETING – Were read and approved at the September 2013 Paris Council meeting. MATTERS ARISING FROM THE MINUTES – None. 2 REPORT ON THE BUSINESS OF THE PARISH COUNCIL SINCE THE PREVIOUS MEETING – the report for the year was read out by the Chairman of the Parish Council – attached to this document. MATTERS ARISING FROM THE REPORT None 3 MATTERS RAISED BY MEMBERS OF THE PARISH PRESENT AT THE MEETING – Mr M Tebbett said that the path by the old car Park by the Old School in Weston under Lizard was more mud than path. It was arranged for Cllr D Maddocks with another councillor would meet Mr Tebbett and look at the area and then decide what was to be done. 4 VISITORS Carla Whelton of the Bradford Estate was welcomed by Cllr D Maddocks. She said that she was there as a contact for now andf in the future to enable the Estate to help and assist with the Community. The Clerk asked if the Estate would look at re-dressing the path in the Weston under Lizard play area as it had been taken over by mud. She said that she would look into that. Cllr D Maddocks lton that the Parish Council was planning to put in a new Play area in Blymhill nad that they were going to be informing the Bradford Estate of that in the near future as it was there land. -

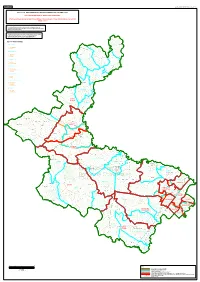

B H I J Q L K M O N a E C D G

SHEET 1, MAP 1 East_Staffordshire:Sheet 1 :Map 1: iteration 1_D THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND ELECTORAL REVIEW OF EAST STAFFORDSHIRE Draft recommendations for ward boundaries in the borough of East Staffordshire June 2020 Sheet 1 of 1 Boundary alignment and names shown on the mapping background may not be up to date. They may differ from the latest boundary information applied as part of this review. This map is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Keeper of Public Records © Crown copyright and database right. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and database right. The Local Government Boundary Commission for England GD100049926 2020. KEY TO PARISH WARDS BURTON CP A ST PETER'S OKEOVER CP B TOWN OUTWOODS CP C CENTRAL D NORTH E SOUTH STANTON CP SHOBNALL CP WOOTTON CP F CANAL G OAKS WOOD MAYFIELD CP STAPENHILL CP RAMSHORN CP H ST PETER'S I STANTON ROAD J VILLAGE UTTOXETER CP ELLASTONE CP K HEATH L TOWN UTTOXETER RURAL CP M BRAMSHALL N LOXLEY O STRAMSHALL WINSHILL CP DENSTONE CP P VILLAGE Q WATERLOO ABBEY & WEAVER CROXDEN CP ROCESTER CP O UTTOXETER NORTH LEIGH CP K M UTTOXETER RURAL CP UTTOXETER CP L UTTOXETER SOUTH N MARCHINGTON CP KINGSTONE CP DRAYCOTT IN THE CLAY CP CROWN TUTBURY CP ROLLESTON ON DOVE CP HANBURY CP DOVE STRETTON CP NEWBOROUGH CP STRETTON C D BAGOTS OUTWOODS CP ABBOTS ANSLOW CP HORNINGLOW BROMLEY CP & OUTWOODS BLITHFIELD CP HORNINGLOW B AND ETON CP E BURTON & ETON G F BURTON CP P SHOBNALL WINSHILL WINSHILL CP SHOBNALL CP HOAR CROSS CP TATENHILL CP Q A BRIZLINCOTE BRANSTON CP ANGLESEY BRIZLINCOTE CP CP BRANSTON & ANGLESEY NEEDWOOD H STAPENHILL I STAPENHILL CP J DUNSTALL CP YOXALL CP BARTON & YOXALL BARTON-UNDER-NEEDWOOD CP WYCHNOR CP 01 2 4 KEY BOROUGH COUNCIL BOUNDARY Kilometres PROPOSED WARD BOUNDARY 1 cm = 0.3819 km PARISH BOUNDARY PROPOSED PARISH WARD BOUNDARY PROPOSED WARD BOUNDARY COINCIDENT WITH PARISH BOUNDARY PROPOSED WARD BOUNDARY COINCIDENT WITH PROPOSED PARISH WARD BOUNDARY BAGOTS PROPOSED WARD NAME WINSHILL CP PARISH NAME. -

STAFFORD BOROUGH COUNCIL - ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT and PLANNING Page 1 of 5

STAFFORD BOROUGH COUNCIL - ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND PLANNING Page 1 of 5 LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS – WEEK ENDING 22 December 2017 APPLICANT/AGENT PROPOSAL & LOCATION TYPE OF APPLICATION APP NO 17/27453/FUL Mr T Warren Proposed extension to Full Application C/O A P Architecture Ltd existing palliative care unit Ms S Brown VALID 13 December 2017 FAO Mr Paul Burton to provide 12 additional E-Innovation Centre Bedrooms, in place of Map Reference: PARISH Barlaston Suite SE 219 existing vacant Barn and E:387807 Telford Campus stables N:337772 WARD Barlaston Priorslee Telford Heyfields Residential UPRN 200001334219 TF2 9FT Home Tittensor Road Tittensor APP NO 17/27599/COU Eccleshall Brewing Change of use from A1 Change of Use Company Ltd (shop) to A4 (drinking Mr E Handley VALID 19 December 2017 C/O Lufton And establishment) - small craft Associates beer bar with an outside Map Reference: PARISH FAO Mr Hugh Lufton (enclosed) areas to the E:392135 4 Beechcroft Avenue front and rear of the N:323459 WARD Forebridge Stafford premises for eating and Staffs drinking UPRN 100032202032 ST16 1BJ 28 Gaolgate Street Stafford ST16 2NT APP NO 17/27623/HOU Mr Andrew Douglas Single storey side Householder C/O Mr Raymond Ward extension to form new Mr G Shilton VALID 18 December 2017 20 Station Road utility Codsall Map Reference: PARISH Wolverhampton 17 Castle House Drive E:390784 WV8 1BY Stafford N:322019 WARD Highfield And Western Staffordshire Downs UPRN 10002090217 APP NO 17/27646/HOU Dr Jon Bingham Proposed single storey Householder C/O Wood Goldstraw -

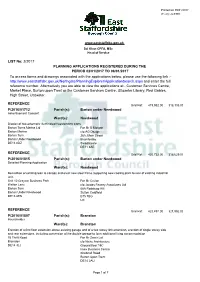

To Access Forms and Drawings Associated with the Applications

Printed On 09/01/2017 Weekly List ESBC www.eaststaffsbc.gov.uk Sal Khan CPFA, MSc Head of Service LIST No: 2/2017 PLANNING APPLICATIONS REGISTERED DURING THE PERIOD 02/01/2017 TO 06/01/2017 To access forms and drawings associated with the applications below, please use the following link :- http://www.eaststaffsbc.gov.uk/Northgate/PlanningExplorer/ApplicationSearch.aspx and enter the full reference number. Alternatively you are able to view the applications at:- Customer Services Centre, Market Place, Burton upon Trent or the Customer Services Centre, Uttoxeter Library, Red Gables, High Street, Uttoxeter. REFERENCE Grid Ref: 419,932.00 : 318,133.00 P/2016/01712 Parish(s): Barton under Needwood Advertisement Consent Ward(s): Needwood Display of two externally illuminated freestanding signs Barton Turns Marina Ltd For Mr B Morgan Barton Marina c/o AG Dezign Barton Turn 26A, Main Street Barton Under Needwood Blackfordby DE13 8DZ Swadlincote DE11 8AE REFERENCE Grid Ref: 420,732.00 : 318,629.00 P/2016/01815 Parish(s): Barton under Needwood Detailed Planning Application Ward(s): Needwood Demolition of existing lean to canopy and erect new steel frame supporting new cooling plant to rear of existing industrial unit. Unit 10 Graycar Business Park For Mr Cruise Walton Lane c/o Jacobs Feasey Associates Ltd Barton Turn 68A Reddicap Hill Barton Under Needwood Sutton Coldfield DE13 8EN B75 7BG UK REFERENCE Grid Ref: 423,497.00 : 321,992.00 P/2016/01807 Parish(s): Branston Householder Ward(s): Branston Erection of a first floor extension above existing -

11Th JANUARY 2016 Meeting

83/92 MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF BLYMHILL AND WESTON-UNDER-LIZARD PARISH COUNCIL HELD AT THE BLYMHILL HILL AND WESTON UNDER LIZARD VILLAGE HALL AT 7.30 PM ON MONDAY 11 JANUARY 2016 PRESENT: Cllr D L Maddocks (Chairman) Cllr A J T Lowe Cllr B Cambidge Cllr G Carter Cllr P D Maddocks Cllr M Stokes (Deputy Chairman) Cllr N Parton IN ATTENDANCE: Mr P Delaloye – Parish Clerk Cllr B J W Cox – South Staffordshire District Council Cllr R A Wright – South Staffordshire District Council (SSDC) Cllr M Sutton – Staffordshire County Council APOLOGIES: Nil 1842 DECLARATIONS OF PECUNIARY INTEREST None 1843 MINUTES OF PREVIOUS MEETINGS RESOLVED: That the minutes of the meeting held on Monday’s 09.11.15 and 07.12.15 be approved as a correct record. 1844 MATTERS ARISING FROM THE PREVIOUS MEETING The On-going Highways issues would be dealt with at the Highways Agenda item. Cllr G Carter reported that he had met the South Staffordshire District Council’s Village Agent, Jan Wright who had attended the November meeting and it had been decided not to do monthly surgeries but would set up some Health and Well-being sessions in the Village Hall. 1845 REPORT OF THE COUNTY COUNCILLOR Cllr M Sutton Reported: o That the Council Tax in Staffordshire would rise, but as yet a decision as to by what amount has not been made. This is to cover Social Care as over a 5 year period the Governments grant for this will be reduced to zero with 50% of that already lost. -

Great Cloud of Witnesses.Indd

A Great Cloud of Witnesses i ii A Great Cloud of Witnesses A Calendar of Commemorations iii Copyright © 2016 by The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of The Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America Portions of this book may be reproduced by a congregation for its own use. Commercial or large-scale reproduction for sale of any portion of this book or of the book as a whole, without the written permission of Church Publishing Incorporated, is prohibited. Cover design and typesetting by Linda Brooks ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-962-3 (binder) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-966-1 (pbk.) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-963-0 (ebook) Church Publishing, Incorporated. 19 East 34th Street New York, New York 10016 www.churchpublishing.org iv Contents Introduction vii On Commemorations and the Book of Common Prayer viii On the Making of Saints x How to Use These Materials xiii Commemorations Calendar of Commemorations Commemorations Appendix a1 Commons of Saints and Propers for Various Occasions a5 Commons of Saints a7 Various Occasions from the Book of Common Prayer a37 New Propers for Various Occasions a63 Guidelines for Continuing Alteration of the Calendar a71 Criteria for Additions to A Great Cloud of Witnesses a73 Procedures for Local Calendars and Memorials a75 Procedures for Churchwide Recognition a76 Procedures to Remove Commemorations a77 v vi Introduction This volume, A Great Cloud of Witnesses, is a further step in the development of liturgical commemorations within the life of The Episcopal Church. These developments fall under three categories. First, this volume presents a wide array of possible commemorations for individuals and congregations to observe. -

1 Christ Episcopal Church Adult Formation 2020 Summer

Christ Episcopal Church Adult Formation 2020 Summer Foundations Course 2020 Guidance from Christians in the midst of Pandemic July 6, 2020 The poet who launched a reform On Sunday, July 14, 1833, the Rev. John Keble (image below), Anglican priest and Professor of Poetry at Oxford University, preached a sermon that accused Parliament of interfering in the internal life of the Church of Ireland (the Anglican Church in Ireland) by reducing its dioceses from 22 to 12 with no consultation of church leaders. Keble’s sermon ignited a storm of controversy for he claimed that the life of the church was not to be determined by the ignorance of public opinion or the whims of Parliament but rather by the gospel of Jesus Christ and the teaching and practices of early Christians – what he called “the apostolic faith.” For English Anglicans who viewed the church as one more agency of the Crown and its government, Keble’s sermon – widely published the moment it ended – gained him violent criticism from many and robust affirmation from others. It was his sermon that led to the emergence of the Oxford Movement – a reform movement in Anglican faith and life. This movement sought to recover “the apostolic faith” by restoring the teaching and practices of early and medieval English Christianity. They viewed the 16th c. reformation as but one moment of reform in the long history of Anglican spirituality: not a tragic break. They criticized the Rationalism that had left Christian faith and life bereft of the mystery of God and God’s presence in the creation and the sacramental life of Christians. -

The Plan for Stafford Borough Part 2 Proposals

The Plan for Stafford Borough: Part 2 Proposals Consultation Stage 2015 The Plan for Stafford Borough Part 2 Proposals Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Settlement Proposals 5 3 Retail Boundaries 49 4 Recognised Industrial Estate Boundaries 55 5 Gypsies, Travellers & Travelling Show People 58 6 Monitoring & Review 59 7 Appendix 60 2 The Plan for Stafford Borough Part 2 Proposals 1 Introduction 1 Introduction What is the Plan for Stafford Borough Part 2? 1.1 The Plan for Stafford Borough Part 2 is the second part of the new Local Plan for Stafford Borough (2011 - 2031). The Local Plan will guide where new development will take place across the Borough area, and identify how places will be shaped in the future. The purpose of the Local Plan is to set out a vision for the development of the Borough, objectives to guide growth, and policies to make sure that new development meets local needs in line with national policy. 1.2 The Local Plan for Stafford Borough consists of three documents: The Plan for Stafford Borough which sets out the strategic policies for the Borough. It contains the development strategy, including identifying the sustainable settlement hierarchy, allocates significant development for Stafford and Stone through Strategic Development Locations and details topic specific policies. The Plan for Stafford Borough was adopted on the 19th June 2014. The Plan for Stafford Borough: Part 2 (formerly known as the Site Allocations document(1)) sets out an approach to development in the sustainable settlement hierarchy, establishes boundaries for the Recognised Industrial Estates, considers retail frontages, and gypsy and traveller allocations. -

General Synod

GENERAL SYNOD FEBRUARY 2017 GROUP OF SESSIONS BUSINESS DONE AT 7 P.M. ON MONDAY 13TH FEBRUARY 2017 WORSHIP The Revd Michael Gisbourne led the Synod in an act of worship. WELCOME 1 The following introductions were made: New members The Rt Revd Michael Ipgrave, the Bishop of Lichfield (who had replaced the Rt Revd Jonathan Gledhill) The Revd James Hollingsworth replacing the Revd John Chitham (Chichester) The Revd Dr Mark Bratton replacing the Revd Ruth Walker (Coventry) The Revd Bill Braviner replacing the Revd Dr John Bellamy (Durham) The Revd Catherine Blair replacing the Revd Canon Karen Hutchinson (Guildford) The Revd Canon James Allison replacing the Revd Canon Jonathan Clark (Leeds) The Revd Duncan Dormor replacing the Revd Canon Mark Tanner (Universities and TEIs) Sarah Maxfield-Phillips replacing Alexandra Podd (Church of England Youth Council) Edward Cox replacing Elliot Swattridge (Church of England Youth Council) REPORT BY THE BUSINESS COMMITTEE (GS 2043) 2 The motion ‘That the Synod do take note of this Report.’ 1 was carried. REVISED DATES OF GROUPS OF SESSIONS IN 2018 3 The motion ‘That this Synod meet on the following dates in 2018: Monday-Saturday 5-10 February Friday-Tuesday 6-10 July Monday-Wednesday 19-21 November (contingency dates).’ was carried. DATES OF GROUPS OF SESSION IN 2019-2020 4 The motion ‘That this Synod meet on the following dates in 2019-2020: 2019 Monday-Saturday 18-23 February Friday-Tuesday 5-9 July Monday-Wednesday 25-27 November (contingency dates) 2020 Monday-Saturday 10-15 February Friday-Tuesday 10-14 July Monday-Wednesday 23-25 November (Inauguration).’ was carried. -

Forms of Address for Clergy the Correct Forms of Address for All Orders of the Anglican Ministry Are As Follows

Forms of Address for Clergy The correct forms of address for all Orders of the Anglican Ministry are as follows: Archbishops In the Canadian Anglican Church there are 4 Ecclesiastical Provinces each headed by an Archbishop. All Archbishops are Metropolitans of an Ecclesiastical Province, but Archbishops of their own Diocese. Use "Metropolitan of Ontario" if your business concerns the Ecclesiastical Province, or "Archbishop of [Diocese]" if your business concerns the Diocese. The Primate of the Anglican Church of Canada is also an Archbishop. The Primate is addressed as The Most Reverend Linda Nicholls, Primate, Anglican Church of Canada. 1. Verbal: "Your Grace" or "Archbishop Germond" 2. Letter: Your Grace or Dear Archbishop Germond 3. Envelope: The Most Reverend Anne Germond, Metropolitan of Ontario Archbishop of Algoma Bishops 1. Verbal: "Bishop Asbil" 2. Letter: Dear Bishop Asbil 3. Envelope: The Right Reverend Andrew J. Asbil Bishop of Toronto In the Diocese of Toronto there are Area Bishops (four other than the Diocesan); envelopes should be addressed: The Rt. Rev. Riscylla Shaw [for example] Area Bishop of Trent Durham [Area] in the Diocese of Toronto Deans In each Diocese in the Anglican Church of Canada there is one Cathedral and one Dean. 1. Verbal: "Dean Vail" or “Mr. Dean” 2. Letter: Dear Dean Vail or Dear Mr. Dean 3. Envelope: The Very Reverend Stephen Vail, Dean of Toronto In the Diocese of Toronto the Dean is also the Rector of the Cathedral. Envelope: The Very Reverend Stephen Vail, Dean and Rector St. James Cathedral Archdeacons Canons 1. Verbal: "Archdeacon Smith" 1. Verbal: "Canon Smith" 2.