Kashmir from Mirpur

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

India-Pakistan: Trade Perception Survey About the Authors

India-Pakistan: Trade Perception Survey ABOUT THE AUTHORS Nisha Taneja, Professor, ICRIER, leads the project on “Strengthening Research and Promoting Multi-level Dialogue for Trade Normalization between India and Pakistan”. She has been engaged in several research projects sponsored by the Ministry of Commerce, Ministry of Textiles and Ministry of Finance, Government of India, as well as the Asian Development Bank (ADB), UNIDO, London School of Economics and the South Asia Network of Economic Research Institutes (SANEI). Her most recent work is on informal trade in South Asia, trade facilitation, non-tariff barriers and various aspects of India-Pakistan trade. She has served on committees set up by the Government of India on Informal Trade, Rules of Origin and Non-tariff Barriers. Dr Taneja holds a PhD in Economics from Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Sanjib Pohit, Professor AcSIR, is presently working as a Senior Principal Scientist at CSIR-National Institute of Science, Technology & Development Studies (NISTADS). Prior to this, he has held research position at National Council for Applied Economic Research, New Delhi (Senior Fellow/Chief Economist), Indian Statistical Institute (Research Fellow), and was a visiting scholar to University of Michigan (Ann Arbor, USA) and Conference Board of Canada. He has been member of several committees of Government of India and has provided Advisory Services to various national and international bodies, including The World Bank, ADB, The Energy & Resource Institute, OECD, CUTS, Price Waterhouse Coopers, Ernst & Young, ICRIER and RIS. Dr Pohit holds a PhD is Economics from the Indian Statistical Institute (ISI), New Delhi. Mishita Mehra was a Research Assistant at ICRIER, associated with the ADB project on “Strengthening the Textiles Sector in South Asia” and the project on “Strengthening Research and Promoting Multi-level Dialogue for Trade Normalization between India and Pakistan”. -

Indigenous Medicinal Knowledge of Common Plants from District Kotli Azad Jammu and Kashmir Pakistan

Journal of Medicinal Plants Research Vol. 6(35), pp. 4961-4967, 12 September, 2012 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/JMPR DOI: 10.5897/JMPR12.703 ISSN 1996-0875 ©2012 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Indigenous medicinal knowledge of common plants from district Kotli Azad Jammu and Kashmir Pakistan Adeel Mahmood1*, Aqeel Mahmood2, Ghulam Mujtaba3, M. Saqlain Mumtaz4, Waqas Khan Kayani4 and Muhammad Azam Khan5 1Department of Plant Sciences, Quaid-I-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan. 2Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Sargodha, Sargodha, Pakistan. 3Department of Microbiology, Quaid-I-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan. 4Department of Biochemistry, Quaid-I-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan. 5Government Post Graduate College (Boys) Hajira, Poonch Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan. Accepted 17 May, 2012 From ancient times, plants are being used in treatment of various diseases. Many of today’s drugs have been derived from plant sources. This research work reveals the indigenous medicinal knowledge of important medicinal plants from district Kotli Azad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK), Pakistan. A total 25 common medicinal plants belonging to the 14 families were reported. Their medicinal and other botanically important uses are described by conducting a meeting and interviews from a total of 137 local inhabitants including 73 males, 47 females and 17 Hakims (herbal specialists). Primary source of indigenous medicines were herbs (56%), shrubs (28%) and trees (16%). Herbal preparations were made by the different plant parts. Most common plant part used to make the herbal preparation was leaf (39%) followed by the root (19%), whole plant (12%), seed (9%), bark (7%), fruit (7%), flower (5%) and tuber (2%). -

Consanguinity and Its Sociodemographic Differentials in Bhimber District, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan

J HEALTH POPUL NUTR 2014 Jun;32(2):301-313 ©INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR DIARRHOEAL ISSN 1606-0997 | $ 5.00+0.20 DISEASE RESEARCH, BANGLADESH Consanguinity and Its Sociodemographic Differentials in Bhimber District, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan Nazish Jabeen, Sajid Malik Human Genetics Program, Department of Animal Sciences, Quaid-i-Azam University, 45320 Islamabad, Pakistan ABSTRACT Kashmiri population in the northeast of Pakistan has strong historical, cultural and linguistic affini- ties with the neighbouring populations of upper Punjab and Potohar region of Pakistan. However, the study of consanguineous unions, which are customarily practised in many populations of Pakistan, revealed marked differences between the Kashmiris and other populations of northern Pakistan with respect to the distribution of marriage types and inbreeding coefficient (F). The current descriptive epidemiological study carried out in Bhimber district of Mirpur division, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan, demonstrated that consanguineous marriages were 62% of the total marriages (F=0.0348). First-cousin unions were the predominant type of marriages and constituted 50.13% of total marital unions. The estimates of inbreeding coefficient were higher in the literate subjects, and consanguinity was witnessed to be rising with increasing literacy level. Additionally, consanguinity was observed to be associated with ethnicity, family structure, language, and marriage arrangements. Based upon these data, a distinct sociobiological structure, with increased stratification and higher genomic homozygos- ity, is expected for this Kashmiri population. In this communication, we present detailed distribution of the types of marital unions and the incidences of consanguinity and inbreeding coefficient (F) across various sociodemographic strata of Bhimber/Mirpuri population. The results of this study would have implication not only for other endogamous populations of Pakistan but also for the sizeable Kashmiri community immigrated to Europe. -

Khalistan & Kashmir: a Tale of Two Conflicts

123 Matthew Webb: Khalistan & Kashmir Khalistan & Kashmir: A Tale of Two Conflicts Matthew J. Webb Petroleum Institute _______________________________________________________________ While sharing many similarities in origin and tactics, separatist insurgencies in the Indian states of Punjab and Jammu and Kashmir have followed remarkably different trajectories. Whereas Punjab has largely returned to normalcy and been successfully re-integrated into India’s political and economic framework, in Kashmir diminished levels of violence mask a deep-seated antipathy to Indian rule. Through a comparison of the socio- economic and political realities that have shaped the both regions, this paper attempts to identify the primary reasons behind the very different paths that politics has taken in each state. Employing a distinction from the normative literature, the paper argues that mobilization behind a separatist agenda can be attributed to a range of factors broadly categorized as either ‘push’ or ‘pull’. Whereas Sikh separatism is best attributed to factors that mostly fall into the latter category in the form of economic self-interest, the Kashmiri independence movement is more motivated by ‘push’ factors centered on considerations of remedial justice. This difference, in addition to the ethnic distance between Kashmiri Muslims and mainstream Indian (Hindu) society, explains why the politics of separatism continues in Kashmir, but not Punjab. ________________________________________________________________ Introduction Of the many separatist insurgencies India has faced since independence, those in the states of Punjab and Jammu and Kashmir have proven the most destructive and potent threats to the country’s territorial integrity. Ostensibly separate movements, the campaigns for Khalistan and an independent Kashmir nonetheless shared numerous similarities in origin and tactics, and for a brief time were contemporaneous. -

AJK at a Glance 2009

1 2 3 DEVELOPMENT SCENARIO General Azad Jammu and Kashmir lies between longitude 730 - 750 and latitude of 33o - 36o and comprises of an area of 5134 Square Miles (13297 Square Kilometers). The topography of the area is mainly hilly and mountainous with valleys and stretches of plains. Azad Kashmir is bestowed with natural beauty having thick forests, fast flowing rivers and winding streams, main rivers are Jehlum, Neelum and Poonch. The climate is sub-tropical highland type with an average yearly rainfall of 1300 mm. The elevation from sea level ranges from 360 meters in the south to 6325 meters in the north. The snow line in winter is around 1200 meters above sea level while in summer, it rises to 3300 meters. According to the 1998 population census the state of Azad Jammu & Kashmir had a population of 2.973 million, which is estimated to have grown to 3.868 million in 2009. Almost 100% population comprises of Muslims. The Rural: urban population ratio is 88:12. The population density is 291 persons per Sq. Km. Literacy rate which was 55% in 1998 census has now raised to 64%. Approximately the infant mortality rate is 56 per 1000 live births, whereas the immunization rate for the children under 5 years of age is more than 95%. The majority of the rural population depends on forestry, livestock, agriculture and non- formal employment to eke out its subsistence. Average per capita income has been estimated to be 1042 US$*. Unemployment ranges from 6.0 to 6.5%. In line with the National trends, indicators of social sector particularly health and population have not shown much proficiency. -

Processing Peace: to Speak in a Different Voice Peace Prints: South Asian Journal of Peacebuilding, Vol

Meenakshi Gopinath: Processing Peace: To Speak in a Different Voice Peace Prints: South Asian Journal of Peacebuilding, Vol. 4, No. 2: Winter 2012 Processing Peace: To Speak in a Different Voice Meenakshi Gopinath Abstract This paper investigates India’s approach to working around the ‘Kashmir’ factor to improve its relationship with Pakistan. The author argues that the Composite Dialogue (CD) framework marked a decisive shift in India’s approach to negotiations from a short term tactical militarist approach to a problem solving orientation in keeping with its self- image of a rising power seeking a place in the sun, through a normative positioning that simultaneously protected its strategic interests. This in the author’s view is an indication that a “peace process” is underway and is likely to yield positive outcomes for not only India but also Pakistan. Author Profile Meenakshi Gopinath is the Founder and Honorary Director of WISCOMP and Principal, Lady Shri Ram College, New Delhi. She was the first woman to serve as member of the National Security Advisory Board of India. Dr. Gopinath is a member of multi-track peace initiatives in Kashmir and between India and Pakistan. She has authored among others Pakistan in Transition, and co-authored Conflict Resolution – Trends and Prospects, Transcending Conflict: A Resource book on Conflict Transformation and Dialogic Engagement and has contributed chapters and articles in several books and journals. Available from http://www.wiscomp.org/peaceprints.htm 1 Meenakshi Gopinath: Processing Peace: To Speak in a Different Voice Peace Prints: South Asian Journal of Peacebuilding, Vol. 4, No. 2: Winter 2012 Processing Peace: To Speak in a Different Voice Meenakshi Gopinath India’s real challenge in balancing its potential ‘big role’ with ‘smart power’ comes from its immediate South Asian neighbourhood. -

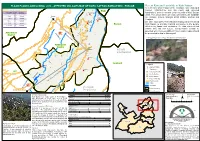

Recent Rain and Landslide in Kotli Sattian

FLASH FLOOD/LANDSLIDING 2016 - AFFECTED VILLAGES MAP OF KOTLI SATTIAN,RAWALPINDI - PUNJAB Recent Rain and Landslide in Kotli Sattian Recent rains which triggered the Landslide have damaged List of Affected Village !> houses, infrastructure and link roads and uprooted !> Bagh !> SN Villages Tehsil District !> Chhajana!> hundreds of trees in several union councils of Kotli Sattian 1 Chaniot Kotli Rawalpindi !> ! Sattian !> !> !> !> !> !> tehsil. The areas which are most affected by the landslide 2 Kamra Kotli Rawalpindi Murree !> !> Sattian !> are Chaniot, Kamra, Wahgal, Malot Sattian, Burhad and 3 Wahgal Kotli Rawalpindi _ !> Malot "' Sattian !> Sattian !> !> Chajana. 4 Malot Kotli Rawalpindi !> !> !> ! Sattian Sattian !> Wahgal ! On 26th April 2016 Prime Minister Nawaz Shareef visited !>!> 5 Burhad Kotli Rawalpindi !> ! Sattian !> !> Poonch !> !> !> Kotli Sattian to provide financial assistance to the people 6 Chhajana Kotli Rawalpindi ! !> Sattian ! affected by floods and landslides. He also directed that Kotli Chijan Road Kotli Chijan Road Patriata Road Patriata Road !> victims who did not receive compensation should be "'!> !> !> !> provided with cheques within 24 hours and a report should Á !> !> !> Abbottabad !> !> Kotli Sattain To Mureee 40 KM !> be presented to him in this regard. District !> !> !>!> ! !> To Murree To A Damaged House View in Village Malot Sattian,Tehsil Kotli Sattain Islamabad-MureeIslamabad-Muree ExpresswayExpressway !> !> !> !> !> 4ö !> !>!> Rawalpindi ! District Kotli ! "' "'Sattian "'! A Z A D "'_ A Z A D !> -

PAKISTAN: REGIONAL RIVALRIES, LOCAL IMPACTS Edited by Mona Kanwal Sheikh, Farzana Shaikh and Gareth Price DIIS REPORT 2012:12 DIIS REPORT

DIIS REPORT 2012:12 DIIS REPORT PAKISTAN: REGIONAL RIVALRIES, LOCAL IMPACTS Edited by Mona Kanwal Sheikh, Farzana Shaikh and Gareth Price DIIS REPORT 2012:12 DIIS REPORT This report is published in collaboration with DIIS . DANISH INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES 1 DIIS REPORT 2012:12 © Copenhagen 2012, the author and DIIS Danish Institute for International Studies, DIIS Strandgade 56, DK-1401 Copenhagen, Denmark Ph: +45 32 69 87 87 Fax: +45 32 69 87 00 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.diis.dk Cover photo: Protesting Hazara Killings, Press Club, Islamabad, Pakistan, April 2012 © Mahvish Ahmad Layout and maps: Allan Lind Jørgensen, ALJ Design Printed in Denmark by Vesterkopi AS ISBN 978-87-7605-517-2 (pdf ) ISBN 978-87-7605-518-9 (print) Price: DKK 50.00 (VAT included) DIIS publications can be downloaded free of charge from www.diis.dk Hardcopies can be ordered at www.diis.dk Mona Kanwal Sheikh, ph.d., postdoc [email protected] 2 DIIS REPORT 2012:12 Contents Abstract 4 Acknowledgements 5 Pakistan – a stage for regional rivalry 7 The Baloch insurgency and geopolitics 25 Militant groups in FATA and regional rivalries 31 Domestic politics and regional tensions in Pakistan-administered Kashmir 39 Gilgit–Baltistan: sovereignty and territory 47 Punjab and Sindh: expanding frontiers of Jihadism 53 Urban Sindh: region, state and locality 61 3 DIIS REPORT 2012:12 Abstract What connects China to the challenges of separatism in Balochistan? Why is India important when it comes to water shortages in Pakistan? How does jihadism in Punjab and Sindh differ from religious militancy in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA)? Why do Iran and Saudi Arabia matter for the challenges faced by Pakistan in Gilgit–Baltistan? These are some of the questions that are raised and discussed in the analytical contributions of this report. -

Pakistan Connection Diasporas @ BBC World Service Audience

Pakistan Connection Diasporas @ BBC World Service Audience Research Report Authors: Marie Gillespie, Sadaf Rivzi, Matilda Andersson, Pippa Virdee, Lucy Michael, Sophie West A BBC World Service / Open University Research Partnership 1 Foreword What does a shop owner in Bradford have in common with a graduate from Princeton USA, a construction worker in Bahrain and a banker in the City of London? All are users of the bbcurdu.com website, and all are part of the global Pakistani diaspora. The term diaspora is used to describe the global dispersion of migrant groups of various kinds. Diasporas are of growing economic, political and cultural significance. In a world where migration, geopolitical dynamics, communication technologies and transport links are continually changing, it is clear that culture and geography no longer map neatly onto one another. Understanding diaspora groups inside and outside its base at Bush House, London, is ever more important for the BBC World Service, too. Diaspora audiences are increasingly influencing the way the BBC conceives and delivers output. For example, over 60% of the weekly users of bbcurdu.com are accessing the site from outside the subcontinent, and this proportion is rising. The same trend has been observed for other BBC language websites. (See BBC World Agenda, September 2008.) The research presented here is based on a unique partnership between BBC World Service Marketing Communication and Audiences (MC&A) and The Open University. It was funded primarily by MC&A but it was also generously supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) though the Diasporas, Migration and Identities Research Programme, which funded a project entitled ‘Tuning In: Diasporic Contact Zones at BBC World Service’ (Grant Award reference AH/ES58693/1). -

Making Borders Irrelevant in Kashmir Will Be Swift and That India-Pakistan Relations Will Rapidly Improve Could Lead to Frustrations

UNiteD StateS iNStitUte of peaCe www.usip.org SpeCial REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPO R T P. R. Chari and Hasan Askari Rizvi This report analyzes the possibilities and practicalities of managing the Kashmir conflict by “making borders irrelevant”—softening the Line of Control to allow the easy movement of people, goods, and services across it. The report draws on the results of a survey of stakeholders and Making Borders public opinion on both sides of the Line of Control. The results of that survey, together with an initial draft of this report, were shown to a group of opinion makers in both countries (former bureaucrats and diplomats, members of the irrelevant in Kashmir armed forces, academics, and members of the media), whose comments were valuable in refining the report’s conclusions. P. R. Chari is a research professor at the Institute Summary for Peace and Conflict Studies in New Delhi and a former member of the Indian Administrative Service. Hasan Askari • Neither India nor Pakistan has been able to impose its preferred solution on the Rizvi is an independent political and defense consultant long-standing Kashmir conflict, and both sides have gradually shown more flexibility in Pakistan and is currently a visiting professor with the in their traditional positions on Kashmir, without officially abandoning them. This South Asia Program of the School of Advanced International development has encouraged the consideration of new, creative approaches to the Studies, Johns Hopkins University. management of the conflict. This report was commissioned by the Center • The approach holding the most promise is a pragmatic one that would “make for Conflict Mediation and Resolution at the United States borders irrelevant”—softening borders to allow movement of people, goods, and Institute of Peace. -

Birth of a Tragedy Kashmir 1947

A TRAGEDY MIR BIRTH OF A TRAGEDY KASHMIR 1947 Alastair Lamb Roxford Books Hertingfordbury 1994 O Alastair Lamb, 1994 The right of Alastair Lamb to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published in 1994 by Roxford Books, Hertingfordbury, Hertfordshire, U.K. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of the publishers. ISBN 0 907129 07 2 Printed in England by Redwood Books, Trowbridge, Wiltshire Typeset by Create Publishing Services Ltd, Bath, Avon Contents Acknowledgements vii I Paramountcy and Partition, March to August 1947 1 1. Introductory 1 2. Paramountcy 4 3. Partition: its origins 13 4. Partition: the Radcliffe Commission 24 5. Jammu & Kashmir and the lapse of Paramountcy 42 I1 The Poonch Revolt, origins to 24 October 1947 54 I11 The Accession Crisis, 24-27 October 1947 81 IV The War in Kashmir, October to December 1947 104 V To the United Nations, October 1947 to 1 January 1948 1 26 VI The Birth of a Tragedy 165 Maps 1. The State of Jammu & Kashmir in relation to its neighbours. ix 2. The State ofJammu & Kashmir. x 3. Stages in the creation of the State ofJammu and Kashmir. xi 4. The Vale of Kashmir. xii ... 5. Partition boundaries in the Punjab, 1947. xlll Acknowledgements ince the publication of my Karhmir. A Disputed Legmy 1846-1990 in S199 1, I have been able to carry out further research into the minutiae of those events of 1947 which resulted in the end ofthe British Indian Empire, the Partition of the Punjab and Bengal and the creation of Pakistan, and the opening stages of the Kashmir dispute the consequences of which are with us still. -

Prevalence of Diabetes Mellitus in Mirpur and Kotli Districts of Azad Jammu & Kashmir (Aj&K)

Sarhad J. Agric. Vol. 23, No. 4, 2007 PREVALENCE OF DIABETES MELLITUS IN MIRPUR AND KOTLI DISTRICTS OF AZAD JAMMU & KASHMIR (AJ&K) Saleem Khan *, M. Abbas *, Fozia Habib ** , Iftikhar H. Khattak *, and N. Iqbal * ABSTRACT Prevalence of Diabetes Mellitus was investigated in the two districts of AJ&K, Mirpur and Kotli. A total of 600 families were randomly selected from both districts for the study. A questionnaire, containing information about diabetes and diet, was filled from a responsible individual of above 30 years of each family. The mean prevalence of diabetes mellitus was 1.77% in the target area. The prevalence was higher in male (1.01%) than female (0.76%). The consumption of milk and meat of people in the area was lower than the recommended amount. The findings indicated that at present, the prevalence of diabetes is not of great concern in AJ&K. However, preventive measure should be taken to avoid the serious consequences of this killer disease. Keywords: Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Diabetes mellitus, Nutrition, Pakistan, Prevalence INTRODUCTION Diabetes mellitus is a major health problem around MATERIALS AND METHODS the globe (King and Rewers, 1993). According to The survey was conducted in the districts Kotli and WHO, prevalence of diabetes mellitus in Pakistan Mirpur of Azad Jammu & Kashmir (AJ&K) from ranked 8 in the world and with present lifestyle this April 20 to September 23, 2005. One city, one ratio will increase (King and Rewers, 1993; King town and one village were selected from each et al., 1995). The prevalence of diabetes in the district as shown in Table I.