A Framework for the Analysis of Visual Representation in Video Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Balance Sheet Also Improves the Company’S Already Strong Position When Negotiating Publishing Contracts

Remedy Entertainment Extensive report 4/2021 Atte Riikola +358 44 593 4500 [email protected] Inderes Corporate customer This report is a summary translation of the report “Kasvupelissä on vielä monta tasoa pelattavana” published on 04/08/2021 at 07:42 Remedy Extensive report 04/08/2021 at 07:40 Recommendation Several playable levels in the growth game R isk Accumulate Buy We reiterate our Accumulate recommendation and EUR 50.0 target price for Remedy. In 2019-2020, Remedy’s (previous Accumulate) strategy moved to a growth stage thanks to a successful ramp-up of a multi-project model and the Control game Accumulate launch, and in the new 2021-2025 strategy period the company plans to accelerate. Thanks to a multi-project model EUR 50.00 Reduce that has been built with controlled risks and is well-managed, as well as a strong financial position, Remedy’s (previous EUR 50.00) Sell preconditions for developing successful games are good. In addition, favorable market trends help the company grow Share price: Recommendation into a clearly larger game studio than currently over this decade. Due to the strongly progressing growth story we play 43.75 the long game when it comes to share valuation. High Low Video game company for a long-term portfolio Today, Remedy is a purebred profitable growth company. In 2017-2018, the company built the basis for its strategy and the successful ramp-up of the multi-project model has been visible in numbers since 2019 as strong earnings growth. In Key indicators 2020, Remedy’s revenue grew by 30% to EUR 41.1 million and the EBIT margin was 32%. -

Dead Space 2: the Sublime, Uncanny and Abject in Survival Horror Games

Dead Space 2: The Sublime, Uncanny and Abject in Survival Horror Games Garth Mc Intosh 404209 Master of Arts by Course Work in Digital Animation 18 February 2015 Supervisor: Hanli Geyser ` 1 Figure 1. Visceral Games, Dead Space II, game cover, 2011. Copyright U.S.A. Electronic Arts. ` 2 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................. 4 HORROR GENRE................................................................................................................................................ 5 ‘DEAD SPACE 2’ ................................................................................................................................................ 6 METHODOLOGY & STRUCTURE ...................................................................................................................... 8 CLARIFICATION OF TERMS .............................................................................................................................. 9 CHAPTER 1 SUBLIME WITHIN NARRATIVE AND MIS-EN-SCENE ....................................10 THE MARKER AND GOYA .............................................................................................................................. 11 AWAKING TO A NIGHTMARE ........................................................................................................................ 13 THE SUBLIME ................................................................................................................................................ -

Evaluating Dynamic Difficulty Adaptivity in Shoot'em up Games

SBC - Proceedings of SBGames 2013 Computing Track – Full Papers Evaluating dynamic difficulty adaptivity in shoot’em up games Bruno Baere` Pederassi Lomba de Araujo and Bruno Feijo´ VisionLab/ICAD Dept. of Informatics, PUC-Rio Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil [email protected], [email protected] Abstract—In shoot’em up games, the player engages in a up game called Zanac [12], [13]2. More recent games that solitary assault against a large number of enemies, which calls implement some kind of difficulty adaptivity are Mario Kart for a very fast adaptation of the player to a continuous evolution 64 [40], Max Payne [20], the Left 4 Dead series [53], [54], of the enemies attack patterns. This genre of video game is and the GundeadliGne series [2]. quite appropriate for studying and evaluating dynamic difficulty adaptivity in games that can adapt themselves to the player’s skill Charles et al. [9], [10] proposed a framework for creating level while keeping him/her constantly motivated. In this paper, dynamic adaptive systems for video games including the use of we evaluate the use of dynamic adaptivity for casual and hardcore player modeling for the assessment of the system’s response. players, from the perspectives of the flow theory and the model Hunicke et al. [27], [28] proposed and tested an adaptive of core elements of the game experience. Also we present an system for FPS games where the deployment of resources, adaptive model for shoot’em up games based on player modeling and online learning, which is both simple and effective. -

CTE: Get Real! Student Filmmaker Toolkit This Guide Will Teach You How to Create a Promotional Video for Your CTE Classes

CTE: Get Real! Student Filmmaker Toolkit This guide will teach you how to create a promotional video for your CTE classes. Here’s what’s included in this guide: ◦ A sample video to guide you. ◦ An overview of all the footage you will need to shoot. ◦ Best practices for setting up, interviewing, and how to get the footage you need. ◦ How to cut this footage down to your final video. 2 Career and Technical Education is hands-on learning that puts students at the center of the action! But not everyone knows how CTE: • Connects to career opportunities like employer internships and job shadows. • Puts students on a path that leads toward a career, college, and education after high school. • Delivers real world skills that make education come alive. 3 Table of Contents 1. Video Basics 6 2. How to tell your CTE story 9 3. Preparing for an interview 13 4. How to interview students, teachers, and employers 24 5. How to capture B-Roll action shots 39 6. How to edit your footage 43 7. Wrap it up! 57 5 We’ve included a sample video to help you create your own video. Click here to view it now. We will refer to specific times in this sample video. Quick Checklist ◦ Pick a CTE class or two to focus on. ◦ Interview students and teachers. ◦ Interview local employers with careers that connect to the CTE class. ◦ Shoot action shots of general classroom activity. ◦ Shoot action shots of employer, or of their employees doing work. ◦ Use a music track. Let’s get started! 4 1 Video Basics 6 Video Basics Six Basic Tips 1. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2000 SEGA CORPORATION Year Ended March 31, 2000 CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS SEGA Enterprises, Ltd

ANNUAL REPORT 2000 SEGA CORPORATION Year ended March 31, 2000 CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS SEGA Enterprises, Ltd. and Consolidated Subsidiaries Years ended March 31, 1998, 1999 and 2000 Thousands of Millions of yen U.S. dollars 1998 1999 2000 2000 For the year: Net sales: Consumer products ........................................................................................................ ¥114,457 ¥084,694 ¥186,189 $1,754,018 Amusement center operations ...................................................................................... 94,521 93,128 79,212 746,227 Amusement machine sales............................................................................................ 122,627 88,372 73,654 693,867 Total ........................................................................................................................... ¥331,605 ¥266,194 ¥339,055 $3,194,112 Cost of sales ...................................................................................................................... ¥270,710 ¥201,819 ¥290,492 $2,736,618 Gross profit ........................................................................................................................ 60,895 64,375 48,563 457,494 Selling, general and administrative expenses .................................................................. 74,862 62,287 88,917 837,654 Operating (loss) income ..................................................................................................... (13,967) 2,088 (40,354) (380,160) Net loss............................................................................................................................. -

October 24, 2019

APT41 10/24/2019 Report #: 201910241000 Agenda • APT41 • Overview • Industry targeting timeline and geographic targeting • A very brief (recent) history of China • China’s economic goals matter to APT41 because… • Why does APT41 matter to healthcare? • Attribution and linkages Image courtesy of PCMag.com • Weapons • Indicators of Compromise (IOCs) • References • Questions Slides Key: Non-Technical: managerial, strategic and high-level (general audience) Technical: Tactical / IOCs; requiring in-depth knowledge (sysadmins, IRT) TLP: WHITE, ID# 201910241000 2 Overview • APT41 • Active since at least 2012 • Assessed by FireEye to be: • Chinese state-sponsored espionage group • Cybercrime actors conducts financial theft for personal gain • Targeted industries: • Healthcare • High-tech • Telecommunications • Higher education • Goals: • Theft of intellectual property • Surveillance • Theft of money • Described by FireEye as… • “highly-sophisticated” • “innovative” and “creative” TLP: WHITE, ID# 201910241000 3 Industry targeting timeline and geographic targeting Image courtesy of FireEye.com • Targeted industries: • Gaming • Healthcare • Pharmaceuticals • High tech • Software • Education • Telecommunications • Travel • Media • Automotive • Geographic targeting: • France, India, Italy, Japan, Myanmar, the Netherlands, Singapore, South Korea, South Africa, Switzerland, Thailand, Turkey, the United Kingdom, the United States and Hong Kong TLP: WHITE, ID# 201910241000 4 A very brief (recent) history of China • First half of 20th century, Chinese -

EA Delivers the First Big Blockbuster Game of 2011 with Dead Space 2

EA Delivers the First Big Blockbuster Game of 2011 With Dead Space 2 The Most Unrelentingly Intense Action Horror Game Hits Retail Shelves; Downloadable Campaigns Revealed with Dead Space 2: Severed Distinctive Dead Space Experience Available for iPhone, iPad and iPod touch REDWOOD CITY, Calif.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- The psychological thrill of deep space rises to an electrifying new level as Visceral Games™, a studio ofElectronic Arts Inc. (NASDAQ:ERTS), today announced the internationally-acclaimed action horror game Dead Space™ is2 now available at retail stores in North America and on January 28 in Europe. This highly- anticipated sequel has been heralded as one of the top games of 2011 by New York Times' Seth Schiesel and has received 25 scores of 90+ from top gaming outlets such as Official Xbox Magazine, Playstation: The Official Magazine and Game Informer. PlayStation: The Official Magazine said that "'Dead Space 2' surpasses the original in every capacity," while IGN calls it "a new gold standard" and Game Informer declares the game "a monster of a sequel, offering bigger scares and more excitement." Visceral Games also announced today Dead Space 2: Severed, an all-new digital download pack that extends the Dead Space 2 story with the addition of two standalone chapters in the single-player game. Dead Space 2: Severed will see the return of Gabe Weller and Lexine Murdock, the two main characters from the award-winning 2009 game, Dead Space Extraction. In Dead Space 2: Severed, the story of Weller and Lexine runs parallel to Isaac's blood-curdling adventure in Dead Space 2, but this time players will take on the role of Gabe Weller. -

Graphic Design and the Cinema: an Application of Graphic Design to the Art of Filmmaking

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Honors Theses Honors College Spring 5-2016 Graphic Design and the Cinema: An Application of Graphic Design to the Art of Filmmaking Kacey B. Holifield University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/honors_theses Part of the Graphic Design Commons Recommended Citation Holifield, Kacey B., "Graphic Design and the Cinema: An Application of Graphic Design to the Art of Filmmaking" (2016). Honors Theses. 403. https://aquila.usm.edu/honors_theses/403 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi Graphic Design and the Cinema: An Application of Graphic Design to the Art of Filmmaking by Kacey Brenn Holifield A Thesis Submitted to the Honors College of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Fine Arts of Graphic Design in the Department of Art and Design May 2016 ii Approved by _______________________________ Jennifer Courts, Ph.D., Thesis Adviser Assistant Professor of Art History _______________________________ Howard M. Paine, Ph.D., Chair Department of Art and Design _______________________________ Ellen Weinauer, Ph.D., Dean Honors College iii Abstract When the public considers different art forms such as painting, drawing and sculpture, it is easy to understand the common elements that unite them. Each is a non- moving art form that begins at the drawing board. -

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

Links to the Past User Research Rage 2

ALL FORMATS LIFTING THE LID ON VIDEO GAMES User Research Links to Game design’s the past best-kept secret? The art of making great Zelda-likes Issue 9 £3 wfmag.cc 09 Rage 2 72000 Playtesting the 16 neon apocalypse 7263 97 Sea Change Rhianna Pratchett rewrites the adventure game in Lost Words Subscribe today 12 weeks for £12* Visit: wfmag.cc/12weeks to order UK Price. 6 issue introductory offer The future of games: subscription-based? ow many subscription services are you upfront, would be devastating for video games. Triple-A shelling out for each month? Spotify and titles still dominate the market in terms of raw sales and Apple Music provide the tunes while we player numbers, so while the largest publishers may H work; perhaps a bit of TV drama on the prosper in a Spotify world, all your favourite indie and lunch break via Now TV or ITV Player; then back home mid-tier developers would no doubt ounder. to watch a movie in the evening, courtesy of etix, MIKE ROSE Put it this way: if Spotify is currently paying artists 1 Amazon Video, Hulu… per 20,000 listens, what sort of terrible deal are game Mike Rose is the The way we consume entertainment has shifted developers working from their bedroom going to get? founder of No More dramatically in the last several years, and it’s becoming Robots, the publishing And before you think to yourself, “This would never increasingly the case that the average person doesn’t label behind titles happen – it already is. -

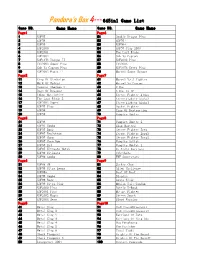

Pandora's Box 4--- 645In1 Game List Game NO

Pandora's Box 4--- 645in1 Game List Game NO. Game Name Game NO. Game Name Page1 Page6 1 KOF97 51 Double Dragon Plus 2 KOF98 52 KOF95+ 3 KOF99 53 KOF96+ 4 KOF2000 54 KOF97 Plus 2003 5 KOF2001 55 The Last Blade 6 KOF2002 56 Snk Vs Capcom 7 KOF10Th Unique II 57 KOF2002 Plus 8 Cth2003 Super Plus 58 Cth2003 9 Snk Vs Capcom Plus 59 KOF10Th Extra Plus 10 KOF2002 Magic II 60 Marvel Super Heroes Page2 Page7 11 King Of Gladiator 61 Marvel Vs S_Fighter 12 Mark Of Wolves 62 Marvel Vs Capcom 13 Samurai Shodown 5 63 X-Men 14 Rage Of Dragons 64 X-Men Vs SF 15 Tokon Matrimelee 65 Street Fighter Alpha 16 The Last Blade 2 66 Streetfighter Alpha2 17 KOF2002 Super 67 Streetfighter Alpha3 18 KOF97 Plus 68 Pocket Fighter 19 KOF94 69 Ring Of Destruction 20 KOF95 70 Vampire Hunter Page3 Page8 21 KOF96 71 Vampire Hunter 2 22 KOF97 Combo 72 Slam Masters 23 KOF97 Boss 73 Street Fighter Zero 24 KOF97 Evolution 74 Street Fighter Zero2 25 KOF97 Chen 75 Street Fighter Zero3 26 KOF97 Chen Bom 76 Vampire Savior 27 KOF97 Lb3 77 Vampire Hunter 2 28 KOF97 Ultimate Match 78 Va Night Warriors 29 KOF98 Ultimate 79 Cyberbots 30 KOF98 Combo 80 WWF Superstars Page4 Page9 31 KOF98 SR 81 Jackie Chan 32 KOF98 Ultra Leona 82 Alien Challenge 33 KOF99+ 83 Best Of Best 34 KOF99 Combo 84 Blandia 35 KOF99 Boss 85 Asura Blade 36 KOF99 Ultra Plus 86 Mobile Suit Gundam 37 KOF2000 Plus 87 Battle K-Road 38 KOF2001 Plus 88 Mutant Fighter 39 KOF2002 Magic 89 Street Smart 40 KOF2004 Hero 90 Blood Warrior Page5 Page10 41 Metal Slug 91 Cadillacs&Dinosaurs 42 Metal Slug 2 92 Cadillacs&Dinosaurs2 -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th.