Observations Upon the Stratigraphical Relations of the Skiddaw Slates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My 214 Story Name: Christopher Taylor Membership Number: 3812 First Fell Climbed

My 214 Story Name: Christopher Taylor Membership number: 3812 First fell climbed: Coniston Old Man, 6 April 2003 Last fell climbed: Great End, 14 October 2019 I was a bit of a late-comer to the Lakes. My first visit was with my family when I was 15. We rented a cottage in Grange for a week at Easter. Despite my parents’ ambitious attempts to cajole my sister Cath and me up Scafell Pike and Helvellyn, the weather turned us back each time. I remember reaching Sty Head and the wind being so strong my Mum was blown over. My sister, 18 at the time, eventually just sat down in the middle of marshy ground somewhere below the Langdale Pikes and refused to walk any further. I didn’t return then until I was 28. It was my Dad’s 60th and we took a cottage in Coniston in April 2003. The Old Man of Coniston became my first summit, and I also managed to get up Helvellyn via Striding Edge with Cath and my brother-in-law Dave. Clambering along the edge and up on to the still snow-capped summit was thrilling. A love of the Lakes, and in particular reaching and walking on high ground, was finally born. Visits to the Lakes became more regular after that, but often only for a week a year as work and other commitments limited opportunities. A number of favourites established themselves: the Langdale Pikes; Lingmoor Fell; Catbells and Wansfell among them. I gradually became more ambitious in the peaks I was willing to take on. -

Endurance Door Brochure

PROTECT YOUR HOME WITH A endurancedoors.co.uk SOLID AND SECURE DOOR INTRODUCTION 1 Safety, Security & Style. It starts with an CONTENTS Endurance door. Why Endurance? 4-5 Endurance Doors are renowned for their strength and security, without compromising on style. DNA of an Endurance Door 6 Secured by Design 7 At 48mm thick and with cross-bonded laminations, an Endurance door delivers unrivaled strength and Preferred Installer Network 8 dimensional stability. It’s the frst choice in delivering the Design Your Dream Door 9 highest level of security, providing home owners with peace of mind. Colours 10-11 Classic Collection 12-37 Made up of 17 laminations, Endurance Doors are almost 10% thicker than most composite doors, guaranteeing Country Collection 38-55 the safety and security of your family and your home. Urban Collection 56-69 With over 50 diferent door designs to choose from, Other Door Styles available in a wide selection of colours with an array & Accessories 70- 85 of diferent door furniture and glazing options, your Endurance Door can be as individual as you are. Glazing Styles 86-87 Glass Matrix 88-89 The Green Promise 90 Quality Standards 91 Classic Collection Country Collection Urban Collection Pages: 12-37 Pages: 38-55 Pages: 56-69 2 VISIT ENDURANCEDOORS.CO.UK TO DESIGN YOUR DOOR INTRODUCTION 3 WHY ENDURANCE? Endurance Doors are renowned for Detailed embossed wood grain texture door their strength and Secured by Design skins, traditional look security, without Secured By Design is the ofcial UK Police with modern technology fagship initiative supporting the principles of ‘designing out crime’. -

Landform Studies in Mosedale, Northeastern Lake District: Opportunities for Field Investigations

Field Studies, 10, (2002) 177 - 206 LANDFORM STUDIES IN MOSEDALE, NORTHEASTERN LAKE DISTRICT: OPPORTUNITIES FOR FIELD INVESTIGATIONS RICHARD CLARK Parcey House, Hartsop, Penrith, Cumbria CA11 0NZ AND PETER WILSON School of Environmental Studies, University of Ulster at Coleraine, Cromore Road, Coleraine, Co. Londonderry BT52 1SA, Northern Ireland (e-mail: [email protected]) ABSTRACT Mosedale is part of the valley of the River Caldew in the Skiddaw upland of the northeastern Lake District. It possesses a diverse, interesting and problematic assemblage of landforms and is convenient to Blencathra Field Centre. The landforms result from glacial, periglacial, fluvial and hillslopes processes and, although some of them have been described previously, others have not. Landforms of one time and environment occur adjacent to those of another. The area is a valuable locality for the field teaching and evaluation of upland geomorphology. In this paper, something of the variety of landforms, materials and processes is outlined for each district in turn. That is followed by suggestions for further enquiry about landform development in time and place. Some questions are posed. These should not be thought of as being the only relevant ones that might be asked about the area: they are intended to help set enquiry off. Mosedale offers a challenge to students at all levels and its landforms demonstrate a complexity that is rarely presented in the textbooks. INTRODUCTION Upland areas attract research and teaching in both earth and life sciences. In part, that is for the pleasure in being there and, substantially, for relative freedom of access to such features as landforms, outcrops and habitats, especially in comparison with intensively occupied lowland areas. -

Rucksack Club Completions Iss:25 22Jun2021

Rucksack Club Completions Iss:25 22Jun2021 Fore Name SMC List Date Final Hill Notes No ALPINE 4000m PEAKS 1 Eustace Thomas Alp4 1929 2 Brian Cosby Alp4 1978 MUNROS 277 Munros & 240 Tops &13 Furth 1 John Rooke Corbett 4 Munros 1930-Jun29 Buchaile Etive Mor - Stob Dearg possibly earlier MunroTops 1930-Jun29 2 John Hirst 9Munros 1947-May28 Ben More - Mull Paddy Hirst was #10 MunroTops 1947 3 Edmund A WtitattakerHodge 11Munros 1947 4 G Graham MacPhee 20Munros 1953-Jul18 Sail Chaorainn (Tigh Mor na Seilge)?1954 MuroTops 1955 5 Peter Roberts 112Munros 1973-Mar24 Seana Braigh MunroTops 1975-Oct Diollaid a'Chairn (544 tops in 1953 Edition) Munros2 1984-Jun Sgur A'Mhadaidh Munros3 1993-Jun9 Beinn Bheoil MunroFurth 2001 Brandon 6 John Mills 120Munros 1973 Ben Alligin: Sgurr Mhor 7 Don Smithies 121Munros 1973-Jul Ben Sgritheall MunroFurth 1998-May Galty Mor MunroTops 2001-Jun Glas Mheall Mor Muros2 2005-May Beinn na Lap 8 Carole Smithies 192Munros 1979-Jul23 Stuc a Chroin Joined 1990 9 Ivan Waller 207Munros 1980-Jun8 Bidean a'choire Sheasgaich MunroTops 1981-Sep13 Carn na Con Du MunroFurth 1982-Oct11 Brandom Mountain 10 Stan Bradshaw 229Munros 1980 MunroTops 1980 MunroFurth 1980 11 Neil Mather 325Munros 1980-Aug2 Gill Mather was #367 Munros2 1996 MunroFurth 1991 12 John Crummett 454Munros 1986-May22 Conival Joined 1986 after compln. MunroFurth 1981 MunroTops 1986 13 Roger Booth 462Munros 1986-Jul10 BeinnBreac MunroFurth 1993-May6 Galtymore MunroTops 1996-Jul18 Mullach Coire Mhic Fheachair Munros2 2000-Dec31 Beinn Sgulaird 14 Janet Sutcliffe 544Munros -

Is Wales' Highest Mountain the Perfect Starter Peak for Kids?

SNOWDON FOR ALL CHILD’S PLAY Is Wales’ highest mountain the perfect starter peak for kids? We sent a rock star to find out... WORDS & PHOTOGRAPHS PHOEBE SMITH ver half a million an ideal first mountain for kids visitors a year would to climb. Naturally, we wanted to suggest the cat is well put that theory to the test, so we and truly out of the went in search of an adventurous bag with Snowdon. family looking for their first taste Arguably, it’s the perfect of proper mountain walking. We mountain for walkers. weren’t expecting that search to Undeniably, it’s one of lead us to a BBC radio presenter OEurope’s most spectacular. This is who also happened to be the lead a peak of extraordinary, unrivalled singer of a multi-million-selling versatility, one that’s historically 1990s rock band. But that’s been used as a training ground exactly what happened. for Everest-bound mountaineers, The message arrived quite but also one where you could unexpectedly one Wednesday achievably stroll with your afternoon. Scanning through my children to the summit. emails, it was a pretty normal day. Then I saw it, the There are no fewer than 10 recognised ways one that stood out above the rest. The subject line to walk or scramble to Snowdon’s pyramidal read: ‘SNOWDONIA – February half-term?’ 1085m top. The beginner-friendly Llanberis Path The message was from Cerys Matthews, the offers the most pedestrian ascent; the South Ridge former frontwoman of rock band Catatonia and holds the key to the mountain’s secret back door; a current BBC Radio 6 Music presenter, who I’d while the notoriously nerve-zapping and razor-sharp accompanied on a wild camping trip a few months ridgeline of Crib Goch is reserved for those with a earlier. -

NLCA06 Snowdonia - Page 1 of 12

National Landscape Character 31/03/2014 NLCA06 Snowdonia Eryri – Disgrifiad cryno Dyma fro eang, wledig, uchel, sy’n cyd-ffinio’n fras â Pharc Cenedlaethol Eryri. Ei nodwedd bennaf yw ei mynyddoedd, o ba rai yr Wyddfa yw mynydd uchaf Cymru a Lloegr, yn 3560’ (1085m) o uchder. Mae’r mynyddoedd eraill yn cynnwys y Carneddau a’r Glyderau yn y gogledd, a’r Rhinogydd a Chadair Idris yn y de. Yma ceir llawer o fryndir mwyaf trawiadol y wlad, gan gynnwys pob un o gopaon Cymru sy’n uwch na 3,000 o droedfeddi. Mae llawer o nodweddion rhewlifol, gan gynnwys cribau llymion, cymoedd, clogwyni, llynnoedd (gan gynnwys Llyn Tegid, llyn mwyaf Cymru), corsydd, afonydd a rhaeadrau. Mae natur serth y tir yn gwneud teithio’n anodd, a chyfyngir mwyafrif y prif ffyrdd i waelodion dyffrynnoedd a thros fylchau uchel. Yn ddaearegol, mae’n ardal amrywiol, a fu â rhan bwysig yn natblygiad cynnar gwyddor daeareg. Denodd sylw rhai o sylfaenwyr yr wyddor, gan gynnwys Charles Darwin, a archwiliodd yr ardal ym 1831. Y mae ymhell, fodd bynnag, o fod yn ddim ond anialdir uchel. Am ganrifoedd, bu’r ardal yn arwydd ysbryd a rhyddid y wlad a’i phobl. Sefydlwyd bwrdeistrefi Dolgellau a’r Bala yng nghyfnod annibyniaeth Cymru cyn y goresgyniad Eingl-normanaidd. Felly, hefyd, llawer o aneddiadau llai ond hynafol fel Dinas Mawddwy. O’i ganolfan yn y Bala, dechreuodd y diwygiad Methodistaidd ar waith trawsffurfio Cymru a’r ffordd Gymreig o fyw yn y 18fed ganrif a’r 19eg. Y Gymraeg yw iaith mwyafrif y trigolion heddiw. -

A Skiddaw Walk Is a Popular Excursion in the Lake Dist

This walk description is from happyhiker.co.uk Skiddaw Walk Starting point and OS Grid reference Ormathwaite free car park (NY 281253) Ordnance Survey map OL4 – The English Lakes, North Western Area. Distance 6.9 miles Traffic light rating Introduction: A Skiddaw walk is a popular excursion in the Lake District as for the thousands of walkers who stay in Keswick, as it is almost the first mountain you see as you step out of the door. It towers above the town. It is also popular because it is one of the few mountains in England over 3,000 feet high, at 3054 ft. (931m) and therefore on many mountaineers’ “must do” lists. A consequence of its popularity is that you are bound to have company on the way but they will be fellow walkers, so decent folk! A plus is that the routes are so well trodden that it is almost impossible to get lost, even in poor visibility. I say “almost” because the route I describe off the summit can be a little tricky to spot if the cloud descends – a not infrequent occurrence over 3000 feet! More about this below. If in doubt, you can always come back the same way but I prefer circular routes. It is a hard walk, very steep ascent almost from the word go and an equally steep descent which can be hard on the knees. There is no scrambling however. The last section is a 1.8 mile walk along the lane behind Applethwaite but do not let that put you off as the views along here, across to the Derwent Fells, are truly fine. -

Snpa-Llanberis-Path-Map.Pdf

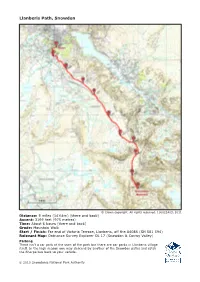

Llanberis Path, Snowdon © Crown copyright. All rights reserved. 100022403, 2011 Distance: 9 miles (14½km) (there and back) Ascent: 3199 feet (975 metres) Time: About 6 hours (there and back) Grade: Mountain Walk Start / Finish: Far end of Victoria Terrace, Llanberis, off the A4086 (SH 581 594) Relevant Map: Ordnance Survey Explorer OL 17 (Snowdon & Conwy Valley) Parking There isn’t a car park at the start of the path but there are car parks in Llanberis village itself. In the high season you may descend by another of the Snowdon paths and catch the Sherpa bus back to your vehicle. © 2010 Snowdonia National Park Authority Llanberis Path, Snowdon Llanberis Path is the longest and most gradual of the six main paths to the summit of Snowdon, and offers fantastic views of Cwm Brwynog, Llanberis and over the Menai straights towards Anglesey. This is the most popular path amongst leisurely walkers as it is thought to be the easiest to walk in mild weather, but in winter, the highest slopes of the path can become very dangerous. The path mainly follows the Snowdon Mountain Railway track, and goes by Hebron, Halfway and Clogwyn stations. Before the railway was opened in 1896, visitors employed guides to lead them to the summit along this path on mule-back. A remarkable geological feature can be seen from the Llanberis path, the Clogwyn Du’r Arddu syncline. The syncline was formed over thousands of years, as the earth moved and transformed horizontal depos- its into vertical layers of rock. Safety Note The Llanberis Path and Snowdon Mountain Railway cross above Clogwyn Coch. -

Welsh 3 Peaks Challenge

WELSH 3 PEAKS CHALLENGE Highlights • 3 peaks! 2334 metres of ascent! 17 miles trekked! In 1-day! Tick! • One of the classic walking challenges in Wales with summiting the three highest peaks • Conquer Snowdon, Cader Idris and Pen-y-Fan • Ascend ridges, cross linked peaks and experience the stellar views and natural beauty of Snowdonia, home to the highest peak in Wales • Trek with pride knowing you are helping support the work of the Snowdonia Society and Cool Earth • Accompanied by local Adventurous Ewe Mountain Leaders • New safety and wellbeing guidelines are in place for this adventure • We look forward to welcoming you to our beautiful homeland of Wales. • #ewecandoit www.yourcompany.com 1 WELCOME Overview Are you ready for an epic mountain adventure embracing the rugged mountains of Wales? Conquering the three highest peaks in Wales, this journey will take you through spectacular landscapes and test your mettle on a tough 1-day adventure. The Welsh 3 Peaks Challenge is made up of three of the highest and most iconic mountains in Wales: Snowdon, Wales’ tallest peak and the highest point in Britain outside the Scottish highlands; Cader Idris, a spectacular peak at the southerly edge of Snowdonia National Park; and Pen y Fan, the highest peak in the Brecon Beacons National Park in South Wales. There’s plenty of mythical legends surrounding these mountains and your local leaders will keep you entertained (or pre-occupied) with stories of giants, villians and poets or explain some of the spectacular geology before you’re greeted with 360 views from each mountain summit, weather permitting of course. -

Required Equipment - Kit Checklist

Required Equipment - Kit Checklist The following items must be carried on all mountains by each team. Each team will be checked for all these items during registration. Subsequent checks will be made before each mountain stage of the event. Team equipment: ¨ First-aid kit (remember special needs of team members i.e. asthmatic etc.) ¨ Compass ¨ Maps (Snowdon, Cadair Idris, Pen-y-Fan) The maps you will require for each mountain are: Snowdon: Ordnance Survey Explorer OL No 17 (1 to 25,000) “Snowdon and Conwy Valley” Cadair Idris: Ordnance Survey Explorer OL No 23 (1 to 25,000) “Cadair Idris and Bala Lake” Pen y Fan: Ordnance Survey Explorer OL No 12 (1 to 25,000) “Brecon Beacons National Park – Western and Central areas” (see maps section of fundraising pack for helpful information) ¨ Note pad and pencil ¨ Mobile phone þ Bothie (will be issued at team briefing) þ Mountain Passport (will be issued at team briefing) Individual requirements: ¨ Rucksack (approx. 30-40 litres) ¨ Waterproof liner ¨ Appropriate footwear (see details below) ¨ Survival bag A survival bag is a person-sized waterproof bag, typically orange in colour, designed to avert the threat of hypothermia from exposure. It is reasonably light, made from strong, waterproof and tear-proof plastic, and provides some amount of thermal insulation and can be purchased at most outdoor stores and online for less than £5. ¨ Set of waterproofs (jacket & trousers) ¨ Hat and gloves ¨ Whistle ¨ Emergency rations (chocolate, dried fruit, nuts, cereal bars etc.) ¨ Torch ¨ Money (in case of emergency) ¨ Drink The amount of fluid required per person will change depending on the weather conditions. -

Roamers' Walks from 9Th March 2017

Roamers’ walks from 9th March 2017 Convenor: Anna Nolan [email protected]; tel: 017687 71197 On 20/12/2018 – Average no of Roamers per walk: 10.66 (512:48) 2017 No Date Walk: Led Walkers: Day 2017 (name, length, duration, drive) by no/ names 1 9/03 Broughton-in-Furness round; Anna 10 Sunny undulating; approx. 14 kilometres = Lyn & John, Sandra but very & Alistair, Liz, Jacqui, windy 8.7 miles (5 hours); 36 miles’ drive Cathy, Barry, Vinnie (a.m.) each way = 1 hour 5 mins 2 23/03 Carron Crag (Grizedale Forest); Anna 7 Sunny start/ end point: High Cross; Jacqui, Alison L, but Dorothy, Bill, Barry, windy undulating; 15.6 kilometres = 9.7 Vinnie miles (5 hours); 24 miles’ drive each way = 50 mins 3 6/04 Stickle Pike; start/ end point: Anna 13 Dry but Broughton Moor; undulating with Jacqui, Margaret T., cold and Helen, Liz, Lyn, windy two separate climbs; 8.5-ish miles; Maureen, Sandra & 1,873 feet ascent for The Knott, a Alistair, Jim, Bill, bit more for the Pike; (5.5 hours); John, Vinnie 27 miles’ drive each way 4 20/04 Alcock Tarn & Nab Scar: start/ Anna 9 Dry but end point: Grasmere; 5.5 miles; Jacqui, Helen, Lyn, cold and Gaynor & David, windy easy climb; roughly 1,400 feet of Pam & Mike, Vinnie ascent; return via Rydal and the coffin route (by bus) 5 4/05 Harrop Tarn – Blea Tarn – Anna 14 Sunny Watendlath – Keswick; Pam & Mike, Sandra & but very Alistair, Lyn, Margaret windy undulating with a climb;10 miles T., Margaret H., Jacqui, (just over 6 hours, including a stop Gaynor, Lesley, at Watendlath) (bus – 555 – to Christine -

Hill Walking & Mountaineering

Hill Walking & Mountaineering in Snowdonia Introduction The craggy heights of Snowdonia are justly regarded as the finest mountain range south of the Scottish Highlands. There is a different appeal to Snowdonia than, within the picturesque hills of, say, Cumbria, where cosy woodland seems to nestle in every valley and each hillside seems neatly manicured. Snowdonia’s hillsides are often rock strewn with deep rugged cwms biting into the flank of virtually every mountainside, sometimes converging from two directions to form soaring ridges which lead to lofty peaks. The proximity of the sea ensures that a fine day affords wonderful views, equally divided between the ever- changing seas and the serried ranks of mountains fading away into the distance. Eryri is the correct Welsh version of the area the English call Snowdonia; Yr Wyddfa is similarly the correct name for the summit of Snowdon, although Snowdon is often used to demarcate the whole massif around the summit. The mountains of Snowdonia stretch nearly fifty miles from the northern heights of the Carneddau, looming darkly over Conwy Bay, to the southern fringes of the Cadair Idris massif, overlooking the tranquil estuary of the Afon Dyfi and Cardigan Bay. From the western end of the Nantlle Ridge to the eastern borders of the Aran range is around twenty- five miles. Within this area lie nine distinct mountain groups containing a wealth of mountain walking possibilities, while just outside the National Park, the Rivals sit astride the Lleyn Peninsula and the Berwyns roll upwards to the east of Bala. The traditional bases of Llanberis, Bethesda, Capel Curig, Betws y Coed and Beddgelert serve the northern hills and in the south Barmouth, Dinas Mawddwy, Dolgellau, Tywyn, Machynlleth and Bala provide good locations for accessing the mountains.