Cryptology: Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Simple Substitution and Caesar Ciphers

Spring 2015 Chris Christensen MAT/CSC 483 Simple Substitution Ciphers The art of writing secret messages – intelligible to those who are in possession of the key and unintelligible to all others – has been studied for centuries. The usefulness of such messages, especially in time of war, is obvious; on the other hand, their solution may be a matter of great importance to those from whom the key is concealed. But the romance connected with the subject, the not uncommon desire to discover a secret, and the implied challenge to the ingenuity of all from who it is hidden have attracted to the subject the attention of many to whom its utility is a matter of indifference. Abraham Sinkov In Mathematical Recreations & Essays By W.W. Rouse Ball and H.S.M. Coxeter, c. 1938 We begin our study of cryptology from the romantic point of view – the point of view of someone who has the “not uncommon desire to discover a secret” and someone who takes up the “implied challenged to the ingenuity” that is tossed down by secret writing. We begin with one of the most common classical ciphers: simple substitution. A simple substitution cipher is a method of concealment that replaces each letter of a plaintext message with another letter. Here is the key to a simple substitution cipher: Plaintext letters: abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz Ciphertext letters: EKMFLGDQVZNTOWYHXUSPAIBRCJ The key gives the correspondence between a plaintext letter and its replacement ciphertext letter. (It is traditional to use small letters for plaintext and capital letters, or small capital letters, for ciphertext. We will not use small capital letters for ciphertext so that plaintext and ciphertext letters will line up vertically.) Using this key, every plaintext letter a would be replaced by ciphertext E, every plaintext letter e by L, etc. -

IMPLEMENTASI ALGORITMA CAESAR, CIPHER DISK, DAN SCYTALE PADA APLIKASI ENKRIPSI DAN DEKRIPSI PESAN SINGKAT, Lumasms

Prosiding Seminar Ilmiah Nasional Komputer dan Sistem Intelijen (KOMMIT 2014) Vol. 8 Oktober 2014 Universitas Gunadarma – Depok – 14 – 15 Oktober 2014 ISSN : 2302-3740 IMPLEMENTASI ALGORITMA CAESAR, CIPHER DISK, DAN SCYTALE PADA APLIKASI ENKRIPSI DAN DEKRIPSI PESAN SINGKAT, LumaSMS Yusuf Triyuswoyo ST. 1 Ferina Ferdianti ST. 2 Donny Ajie Baskoro ST. 3 Lia Ambarwati ST. 4 Septiawan ST. 5 1,2,3,4,5Jurusan Manajemen Sistem Informasi, Universitas Gunadarma [email protected] Abstrak Short Message Service (SMS) merupakan salah satu cara berkomunikasi yang banyak digunakan oleh pengguna telepon seluler. Namun banyaknya pengguna telepon seluler yang menggunakan layanan SMS, tidak diimbangi dengan faktor keamanan yang ada pada layanan tersebut. Banyak pengguna telepon seluler yang belum menyadari bahwa SMS tidak menjamin integritas dan keamanan pesan yang disampaikan. Ada beberapa risiko yang dapat mengancam keamanan pesan pada layanan SMS, diantaranya: SMS spoofing, SMS snooping, dan SMS interception. Untuk mengurangi risiko tersebut, maka dibutuhkan sebuah sistem keamanan pada layanan SMS yang mampu menjaga integritas dan keamanan isi pesan. Dimana tujuannya ialah untuk menutupi celah pada tingkat keamanan SMS. Salah satu penanggulangannya ialah dengan menerapkan algoritma kriptografi, yaitu kombinasi atas algoritma Cipher Disk, Caesar, dan Scytale pada pesan yang akan dikirim. Tujuan dari penulisan ini adalah membangun aplikasi LumaSMS, dengan menggunakan kombinasi ketiga algoritma kriptografi tersebut. Dengan adanya aplikasi ini diharapkan mampu mengurangi masalah keamanan dan integritas SMS. Kata Kunci: caesar, cipher disk, kriptografi, scytale, SMS. PENDAHULUAN dibutuhkan dikarenakan SMS mudah digunakan dan biaya yang dikeluarkan Telepon seluler merupakan salah untuk mengirim SMS relatif murah. satu hasil dari perkembangan teknologi Namun banyaknya pengguna komunikasi. -

Cryptanalysis of Mono-Alphabetic Substitution Ciphers Using Genetic Algorithms and Simulated Annealing Shalini Jain Marathwada Institute of Technology, Dr

Vol. 08 No. 01 2018 p-ISSN 2202-2821 e-ISSN 1839-6518 (Australian ISSN Agency) 82800801201801 Cryptanalysis of Mono-Alphabetic Substitution Ciphers using Genetic Algorithms and Simulated Annealing Shalini Jain Marathwada Institute of Technology, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Marathwada University, India Nalin Chhibber University of Waterloo, Ontario, Canada Sweta Kandi Marathwada Institute of Technology, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Marathwada University, India ABSTRACT – In this paper, we intend to apply the principles of genetic algorithms along with simulated annealing to cryptanalyze a mono-alphabetic substitution cipher. The type of attack used for cryptanalysis is a ciphertext-only attack in which we don’t know any plaintext. In genetic algorithms and simulated annealing, for ciphertext-only attack, we need to have the solution space or any method to match the decrypted text to the language text. However, the challenge is to implement the project while maintaining computational efficiency and a high degree of security. We carry out three attacks, the first of which uses genetic algorithms alone, the second which uses simulated annealing alone and the third which uses a combination of genetic algorithms and simulated annealing. Key words: Cryptanalysis, mono-alphabetic substitution cipher, genetic algorithms, simulated annealing, fitness I. Introduction II. Mono-alphabetic substitution cipher Cryptanalysis involves the dissection of computer systems by A mono-alphabetic substitution cipher is a class of substitution unauthorized persons in order to gain knowledge about the ciphers in which the same letters of the plaintext are replaced unknown aspects of the system. It can be used to gain control by the same letters of the ciphertext. -

Assignment 4 Task 1: Frequency Analysis (100 Points)

Assignment 4 Task 1: Frequency Analysis (100 points) The cryptanalyst can benefit from some inherent characteristics of the plaintext language to launch a statistical attack. For example, we know that the letter E is the most frequently used letter in English text. The cryptanalyst finds the mostly-used character in the ciphertext and assumes that the corresponding plaintext character is E. After finding a few pairs, the analyst can find the key and use it to decrypt the message. To prevent this type of attack, the cipher should hide the characteristics of the language. Table 1 contains frequency of characters in English. Table 1 Frequency of characters in English Cryptogram puzzles are solved for enjoyment and the method used against them is usually some form of frequency analysis. This is the act of using known statistical information and patterns about the plaintext to determine it. In cryptograms, each letter of the alphabet is encrypted to another letter. This table of letter-letter translations is what makes up the key. Because the letters are simply converted and nothing is scrambled, the cipher is left open to this sort of analysis; all we need is that ciphertext. If the attacker knows that the language used is English, for example, there are a great many patterns that can be searched for. Classic frequency analysis involves tallying up each letter in the collected ciphertext and comparing the percentages against the English language averages. If the letter "M" is most common then it is reasonable to guess that "E"-->"M" in the cipher because E is the most common letter in the English language. -

John F. Byrne's Chaocipher Revealed

John F. Byrne’s Chaocipher Revealed John F. Byrne’s Chaocipher Revealed: An Historical and Technical Appraisal MOSHE RUBIN1 Abstract Chaocipher is a method of encryption invented by John F. Byrne in 1918, who tried unsuccessfully to interest the US Signal Corp and Navy in his system. In 1953, Byrne presented Chaocipher-encrypted messages as a challenge in his autobiography Silent Years. Although numerous students of cryptanalysis attempted to solve the challenge messages over the years, none succeeded. For ninety years the Chaocipher algorithm was a closely guarded secret known only to a handful of persons. Following fruitful negotiations with the Byrne family during the period 2009-2010, the Chaocipher papers and materials have been donated to the National Cryptologic Museum in Ft. Meade, MD. This paper presents a comprehensive historical and technical evaluation of John F. Byrne and his Chaocipher system. Keywords ACA, American Cryptogram Association, block cipher encryption modes, Chaocipher, dynamic substitution, Greg Mellen, Herbert O. Yardley, John F. Byrne, National Cryptologic Museum, Parker Hitt, Silent Years, William F. Friedman 1 Introduction John Francis Byrne was born on 11 February 1880 in Dublin, Ireland. He was an intimate friend of James Joyce, the famous Irish writer and poet, studying together in Belvedere College and University College in Dublin. Joyce based the character named Cranly in Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man on Byrne, used Byrne’s Dublin residence of 7 Eccles Street as the home of Leopold and Molly Bloom, the main characters in Joyce’s Ulysses, and made use of real-life anecdotes of himself and Byrne as the basis of stories in Ulysses. -

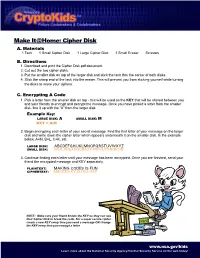

Cipher Disk A

Make It@Home: Cipher Disk A. Materials 1 Tack 1 Small Cipher Disk 1 Large Cipher Disk 1 Small Eraser Scissors B. Directions 1. Download and print the Cipher Disk.pdf document. 2. Cut out the two cipher disks. 3. Put the smaller disk on top of the larger disk and stick the tack thru the center of both disks. 4. Stick the sharp end of the tack into the eraser. This will prevent you from sticking yourself while turning the disks to make your ciphers. C. Encrypting A Code 1. Pick a letter from the smaller disk on top - this will be used as the KEY that will be shared between you and your friends to encrypt and decrypt the message. Once you have picked a letter from the smaller disk, line it up with the “A” from the larger disk. Example Key: LARGE DISK: A SMALL DISK: M KEY = A:M 2. Begin encrypting each letter of your secret message. Find the first letter of your message on the larger disk and write down the cipher letter which appears underneath it on the smaller disk. In the example below, A=M, B=L, C=K, etc. LARGE DISK: ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ SMALL DISK: MLKJIHGFEDCBAZYXWVUTSRQPON 3. Continue finding each letter until your message has been encrypted. Once you are finished, send your friend the encrypted message and KEY seperately. PLAINTEXT: MAKING CODES IS FUN CIPHERTEXT: AMCEZG KYJIU EU HSZ NOTE: Make sure your friend knows the KEY so they can use their Cipher Disk to break the code. For a super secure cipher, create a new KEY every time you send a message OR change the KEY every time you encrypt a letter. -

Shift Cipher Substitution Cipher Vigenère Cipher Hill Cipher

Lecture 2 Classical Cryptosystems Shift cipher Substitution cipher Vigenère cipher Hill cipher 1 Shift Cipher • A Substitution Cipher • The Key Space: – [0 … 25] • Encryption given a key K: – each letter in the plaintext P is replaced with the K’th letter following the corresponding number ( shift right ) • Decryption given K: – shift left • History: K = 3, Caesar’s cipher 2 Shift Cipher • Formally: • Let P=C= K=Z 26 For 0≤K≤25 ek(x) = x+K mod 26 and dk(y) = y-K mod 26 ʚͬ, ͭ ∈ ͔ͦͪ ʛ 3 Shift Cipher: An Example ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 • P = CRYPTOGRAPHYISFUN Note that punctuation is often • K = 11 eliminated • C = NCJAVZRCLASJTDQFY • C → 2; 2+11 mod 26 = 13 → N • R → 17; 17+11 mod 26 = 2 → C • … • N → 13; 13+11 mod 26 = 24 → Y 4 Shift Cipher: Cryptanalysis • Can an attacker find K? – YES: exhaustive search, key space is small (<= 26 possible keys). – Once K is found, very easy to decrypt Exercise 1: decrypt the following ciphertext hphtwwxppelextoytrse Exercise 2: decrypt the following ciphertext jbcrclqrwcrvnbjenbwrwn VERY useful MATLAB functions can be found here: http://www2.math.umd.edu/~lcw/MatlabCode/ 5 General Mono-alphabetical Substitution Cipher • The key space: all possible permutations of Σ = {A, B, C, …, Z} • Encryption, given a key (permutation) π: – each letter X in the plaintext P is replaced with π(X) • Decryption, given a key π: – each letter Y in the ciphertext C is replaced with π-1(Y) • Example ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ πBADCZHWYGOQXSVTRNMSKJI PEFU • BECAUSE AZDBJSZ 6 Strength of the General Substitution Cipher • Exhaustive search is now infeasible – key space size is 26! ≈ 4*10 26 • Dominates the art of secret writing throughout the first millennium A.D. -

Network Security

Cristina Nita-Rotaru CS6740: Network security Additional material: Cryptography 1: Terminology and classic ciphers Readings for this lecture Required readings: } Cryptography on Wikipedia Interesting reading } The Code Book by Simon Singh 3 Cryptography The science of secrets… } Cryptography: the study of mathematical techniques related to aspects of providing information security services (create) } Cryptanalysis: the study of mathematical techniques for attempting to defeat information security services (break) } Cryptology: the study of cryptography and cryptanalysis (both) 4 Cryptography Basic terminology in cryptography } cryptography } plaintexts } cryptanalysis } ciphertexts } cryptology } keys } encryption } decryption plaintext ciphertext plaintext Encryption Decryption Key_Encryption Key_Decryption 5 Cryptography Cryptographic protocols } Protocols that } Enable parties } Achieve objectives (goals) } Overcome adversaries (attacks) } Need to understand } Who are the parties and the context in which they act } What are the goals of the protocols } What are the capabilities of adversaries 6 Cryptography Cryptographic protocols: Parties } The good guys } The bad guys Alice Carl Bob Eve Introduction of Alice and Bob Check out wikipedia for a longer attributed to the original RSA paper. list of malicious crypto players. 7 Cryptography Cryptographic protocols: Objectives/Goals } Most basic problem: } Ensure security of communication over an insecure medium } Basic security goals: } Confidentiality (secrecy, confidentiality) } Only the -

Algorithms and Mechanisms Historical Ciphers

Algorithms and Mechanisms Cryptography is nothing more than a mathematical framework for discussing the implications of various paranoid delusions — Don Alvarez Historical Ciphers Non-standard hieroglyphics, 1900BC Atbash cipher (Old Testament, reversed Hebrew alphabet, 600BC) Caesar cipher: letter = letter + 3 ‘fish’ ‘ilvk’ rot13: Add 13/swap alphabet halves •Usenet convention used to hide possibly offensive jokes •Applying it twice restores the original text Substitution Ciphers Simple substitution cipher: a=p,b=m,c=f,... •Break via letter frequency analysis Polyalphabetic substitution cipher 1. a = p, b = m, c = f, ... 2. a = l, b = t, c = a, ... 3. a = f, b = x, c = p, ... •Break by decomposing into individual alphabets, then solve as simple substitution One-time Pad (1917) Message s e c r e t 18 5 3 17 5 19 OTP +15 8 1 12 19 5 7 13 4 3 24 24 g m d c x x OTP is unbreakable provided •Pad is never reused (VENONA) •Unpredictable random numbers are used (physical sources, e.g. radioactive decay) One-time Pad (ctd) Used by •Russian spies •The Washington-Moscow “hot line” •CIA covert operations Many snake oil algorithms claim unbreakability by claiming to be a OTP •Pseudo-OTPs give pseudo-security Cipher machines attempted to create approximations to OTPs, first mechanically, then electronically Cipher Machines (~1920) 1. Basic component = wired rotor •Simple substitution 2. Step the rotor after each letter •Polyalphabetic substitution, period = 26 Cipher Machines (ctd) 3. Chain multiple rotors Each rotor steps the next one when a full -

Lecture 3: Classical Cryptosystems (Vigenère Cipher)

CS408 Cryptography & Internet Security Lecture 3: Classical cryptosystems (Vigenère cipher) Reza Curtmola Department of Computer Science / NJIT Towards Poly-alphabetic Substitution Ciphers l Main weaknesses of mono-alphabetic substitution ciphers § each letter in the ciphertext corresponds to only one letter in the plaintext letter l Idea for a stronger cipher (1460’s by Alberti) § use more than one cipher alphabet, and switch between them when encrypting different letters l Developed into a practical cipher by Blaise de Vigenère (published in 1586) § Was known at the time as the “indecipherable cipher” CS 408 Lecture 3 / Spring 2015 2 1 The Vigenère Cipher Definition: n Given m (a positive integer), P = C = (Z26) , and K = (k1, k2, … , km) a key, we define: Encryption: ek(p1, p2…, pm) = (p1+k1, p2+k2…, pm+km) (mod 26) Decryption: dk(c1, c2…, cm) = (c1-k1, c2-k2 …, cm- km) (mod 26) Example: key = LUCK (m = 4) plaintext: C R Y P T O G R A P H Y key: L U C K L U C K L U C K ciphertext: N L A Z E I I B L J J I CS 408 Lecture 3 / Spring 2015 3 Security of Vigenère Cipher l Vigenère masks the frequency with which a character appears in a language: one letter in the ciphertext corresponds to multiple letters in the plaintext. Makes the use of frequency analysis more difficult. l Any message encrypted by a Vigenère cipher is a collection of as many shift ciphers as there are letters in the key. CS 408 Lecture 3 / Spring 2015 4 2 Vigenère Cipher: Cryptanalysis l Find the length of the key. -

Report Eric Camellini 4494164 [email protected]

1 IN4191 SECURITY AND CRYPTOGRAPHY 2015-2016 Assignment 1 - Report Eric Camellini 4494164 [email protected] Abstract—In this report, I explain how I deciphered a message library: this function finds existing words in the text using a encrypted with a simple substitution cipher. I focus on how I used dictionary of the selected language. frequency analysis to understand the substitution pattern and I With this approach I observed that after the frequency-based also give a brief explanation of the cipher used. letter replacement the language with more word matches (with a minimum word length of 3 characters) was Dutch, so I focused on it trying to compare its letter frequency with the I. INTRODUCTION one of the ciphertext. The letters in order of frequency were The objective of this work was to decipher an encrypted the following: message using frequency analysis or brute forcing, knowing that: Ciphertext: ”ranevzbgqhoutwyfsxjipcm” • It seemed to be encrypted using a simple cipher; Dutch language: ”enatirodslghvkmubpwjczfxyq” • It was probably written without spaces or punctuation; Looking at the two lists I observed the following pattern: • The language used could be English, Dutch, German or Turkish. • The first 3 most frequent letters in the text have (r, a, The ciphertext was the following: n) a 13 letters distance in the alphabet from the 3 most frequent ones in the Dutch language (e, n, a). VaqrprzoreoeratraWhyvhfraJnygreUbyynaqreqrgjrroebrefi • Other frequent letters preserve this 13 letters distance naRqvguZnetbganneNzfgreqnzNaarjvytenntzrrxbzraznnezbrga pattern: for example the letters ’e’ and ’v’ are in the 6 btrrarragvwqwrovwbznoyvwiraBznmnyurgzbrvyvwxuroorabz most frequent letters in the ciphertex, and they are 13 NaarabtrracnnejrxraqnnegrubhqrafpuevwsgRqvguSenaxvarra letters distant from ’r’ and ’i’ respectively, that are in oevrsnnaTregehqAnhznaauhaiebrtrerohhezrvfwrvaSenaxshegn the 6 most frequent ones in the Dutch language. -

Cryptology: an Historical Introduction DRAFT

Cryptology: An Historical Introduction DRAFT Jim Sauerberg February 5, 2013 2 Copyright 2013 All rights reserved Jim Sauerberg Saint Mary's College Contents List of Figures 8 1 Caesar Ciphers 9 1.1 Saint Cyr Slide . 12 1.2 Running Down the Alphabet . 14 1.3 Frequency Analysis . 15 1.4 Linquist's Method . 20 1.5 Summary . 22 1.6 Topics and Techniques . 22 1.7 Exercises . 23 2 Cryptologic Terms 29 3 The Introduction of Numbers 31 3.1 The Remainder Operator . 33 3.2 Modular Arithmetic . 38 3.3 Decimation Ciphers . 40 3.4 Deciphering Decimation Ciphers . 42 3.5 Multiplication vs. Addition . 44 3.6 Koblitz's Kid-RSA and Public Key Codes . 44 3.7 Summary . 48 3.8 Topics and Techniques . 48 3.9 Exercises . 49 4 The Euclidean Algorithm 55 4.1 Linear Ciphers . 55 4.2 GCD's and the Euclidean Algorithm . 56 4.3 Multiplicative Inverses . 59 4.4 Deciphering Decimation and Linear Ciphers . 63 4.5 Breaking Decimation and Linear Ciphers . 65 4.6 Summary . 67 4.7 Topics and Techniques . 67 4.8 Exercises . 68 3 4 CONTENTS 5 Monoalphabetic Ciphers 71 5.1 Keyword Ciphers . 72 5.2 Keyword Mixed Ciphers . 73 5.3 Keyword Transposed Ciphers . 74 5.4 Interrupted Keyword Ciphers . 75 5.5 Frequency Counts and Exhaustion . 76 5.6 Basic Letter Characteristics . 77 5.7 Aristocrats . 78 5.8 Summary . 80 5.9 Topics and Techniques . 81 5.10 Exercises . 81 6 Decrypting Monoalphabetic Ciphers 89 6.1 Letter Interactions . 90 6.2 Decrypting Monoalphabetic Ciphers .