A Hip-Hop Hamilton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hamilton at the Paramount Seattle

SPECIAL EDITION • FEBRUARY 2018 ENCORE ARTS PROGRAMS • SPECIAL EDITION HAMILTON FEBRUARY 2018 FEBRUARY PROGRAMS • SPECIAL EDITION HAMILTON ARTS ENCORE HAMILTON February 6 – March 18, 2018 Cyan Magenta Yellow Black Inks Used: 1/10/18 12:56 PM 1/11/18 11:27 AM Changes Prev AS-IS Changes See OK OK with Needs INITIALS None Carole Guizetti — Joi Catlett Joi None Kristine/Ethan June Ashley Nelu Wijesinghe Nelu Vivian Che Barbara Longo Barbara Proofreader: Regulatory: CBM Lead: Prepress: Print Buyer: Copywriter: CBM: · · · · Visual Pres: Producer: Creative Mgr Promo: Designer: Creative Mgr Lobby: None None 100% A N N U A L UPC: Dieline: RD Print Scale: 1-9-2018 12:44 PM 12:44 1-9-2018 D e si gn Galle r PD y F Date: None © 2018 Starbucks Co ee Company. All rights reserved. All rights reserved. ee Company. SBX18-332343 © 2018 Starbucks Co x 11.125" 8.625" Tickets at stgpresents.org SKU #: Bleed: SBUX FTP Email 12/15/2017 STARBUCKS 23 None 100% OF TICKET SALES GOOF TOTHE THE PARTICIPATING MUSIC PROGRAMS HIGH SCHOOL BANDS — FRIDAY, MARCH 30 AT 7PM SBX18-332343 HJCJ Encore Ad Encore HJCJ blongo014900 SBX18-332343 HotJavaCoolJazz EncoreAd.indd HotJavaCoolJazz SBX18-332343 None RELEASED 1-9-2018 Hot Java Cool Jazz None None None x 10.875" 8.375" D i sk SCI File Cabinet O t h e r LIVE AT THE PARAMOUNT IMPORTANT NOTES: IMPORTANT Vendor: Part #: Trim: Job Number: Layout: Job Name: Promo: File Name: Proj Spec: Printed by: Project: RELEASE BEFORE: BALLARD | GARFIELD | MOUNTLAKE TERRACE | MOUNT SI | ROOSEVELT COMPANY Seattle, 98134 WA 2401 Utah Avenue South2401 -

ACRONYM 13 - Round 6 Written by Danny Vopava, Erik Nelson, Blake Andert, Rahul Rao-Potharaju, William Golden, and Auroni Gupta

ACRONYM 13 - Round 6 Written by Danny Vopava, Erik Nelson, Blake Andert, Rahul Rao-Potharaju, William Golden, and Auroni Gupta 1. This album was conceived after the master tapes to the album Cigarettes and Valentines were stolen. A letter reading "I got a rock and roll girlfriend" is described in a multi-part song at the end of this album. A teenager described in this albumis called the "son of rage and love" and can't fully remember a figure he only calls (*) "Whatsername." A "redneck agenda" is decried in the title song of this album, which inspired a musical centered onthe "Jesus of Suburbia." "Boulevard of Broken Dreams" appears on, for 10 points, what 2004 album by Green Day? ANSWER: American Idiot <Nelson> 2. In 1958, Donald Duck became the first non-human to appear in this TV role, which was originated by Douglas Fairbanks and William C. DeMille. James Franco appeared in drag while serving in this role, which went unfilled in 2019 after (*) Kevin Hart backed out. The most-retweeted tweet ever was initiated by a woman occupying this role, which was done nine other times by Billy Crystal. While holding this role in 2017, Jimmy Kimmel shouted "Warren, what did you do?!" upon the discovery of an envelope mix-up. For 10 points, name this role whose holder cracks jokes between film awards. ANSWER: hosting the Oscars [accept similar answers describing being the host of the Academy Awards; prompt on less specific answers like award show host or TV show host] <Nelson> 3. As of December 2019, players of this game can nowmake Dinosaur Mayonnaise thanks to its far-reaching 1.4 version update, nicknamed the "Everything Update." Every single NPC in this game hates being given the Mermaid's Pendant at the Festival of the Winter Star because it's only meant to be used for this game's (*) marriage proposals. -

Mixed Folios

mixed folios 447 The Anthology Series – 581 Folk 489 Piano Chord Gold Editions 473 40 Sheet Music Songbooks 757 Ashley Publications Bestsellers 514 Piano Play-Along Series 510 Audition Song Series 444 Freddie the Frog 660 Pop/Rock 540 Beginning Piano Series 544 Gold Series 501 Pro Vocal® Series 448 The Best Ever Series 474 Grammy Awards 490 Reader’s Digest Piano 756 Big Band/Swing Songbooks 446 Recorder Fun! 453 The Big Books of Music 475 Great Songs Series 698 Rhythm & Blues/Soul 526 Blues 445 Halloween 491 Rock Band Camp 528 Blues Play-Along 446 Harmonica Fun! 701 Sacred, Christian & 385 Broadway Mixed Folios 547 I Can Play That! Inspirational 380 Broadway Vocal 586 International/ 534 Schirmer Performance Selections Multicultural Editions 383 Broadway Vocal Scores 477 It’s Easy to Play 569 Score & Sound Masterworks 457 Budget Books 598 Jazz 744 Seasons of Praise 569 CD Sheet Music 609 Jazz Piano Solos Series ® 745 Singalong & Novelty 460 Cheat Sheets 613 Jazz Play-Along Series 513 Sing in the Barbershop 432 Children’s Publications 623 Jewish Quartet 478 The Joy of Series 703 Christian Musician ® 512 Sing with the Choir 530 Classical Collections 521 Keyboard Play-Along Series 352 Songwriter Collections 548 Classical Play-Along 432 Kidsongs Sing-Alongs 746 Standards 541 Classics to Moderns 639 Latin 492 10 For $10 Sheet Music 542 Concert Performer 482 Legendary Series 493 The Ultimate Series 570 Country 483 The Library of… 495 The Ultimate Song 577 Country Music Pages Hall of Fame 643 Love & Wedding 496 Value Songbooks 579 Cowboy Songs -

OFFICIAL PROGRAM for BROADWAY in DETROIT at the Detroit Opera House MADE IN

OFFICIAL PROGRAM FOR BROADWAY IN DETROIT AT THE Detroit Opera HOUSE MADE IN PEOPLE MAGNET. REALIZES EVERY DAY IS A BLESSING. ENJOYS WORKING AT COSTCO. APPRECIATES HIS SECOND CHANCE IN LIFE. 100 % SAM ZIEMAN XL CHARACTER We have character. Thousands of them, actually. Like Sam, our residents won’t just steal the show... they’ll steal your heart. Visit americanhouse.com/testimonials to watch videos and learn more about our incredible cast of characters. For information on our communities visit americanhouse.com or call (800) 351-5224. Residences • Dining • Activities • Education • Wellness • Transportation • Support Services* TDD (800) 649-3777 *Support Services provided by third party not affiliated with American House. job number: 50679_B24_C1-1 date: 10/07/11 client: RLX advertiser: RLX dtp: color: cs: acct: client: please contact thelab at 212-209-1333 with any questions or concerns regarding these materials. Proof: 12/23/11; 8:30PM Million Dollar Quartet JERRY LEE JOHNNY Tom Hulce & Ira Pittelman Work Light Productions Publication: ELVIS CARL Vivek J. Tiwary Latitude Link Scott M. Delman Broadway in Detroit programAllan for S. Gordon MagicSpace Entertainment PRESLEY PERKINS “Wicked” LEWIS CASH In Association with Run dates: 12/7/11 tpAbbie 12/31/11 M. Strassler John Domo Lorenzo Thione & Jay Kuo Size: full page full bleed Present trim size: 5-3/8” x 8-3/8” THE BROADWAY MUSICAL bleed: 1/8” inside margin: 1/4” For: Nederlander Detroit (Fisher Theatre & others) Music by Lyrics by Design: Frank Bach, Green Day Billie Joe Armstrong INSPIRED BY THE ELECTRIFYING TRUE STORY Bach & Associates; Book by Phone 313-822-43038;Billie Joe Armstrong and Michael Mayer [email protected] Van Hughes Scott J. -

HAMILTON Project Profile 6 8 20

“HAMILTON” ONE-LINER: An unforgettable cinematic stage performance, the filmed version of the original Broadway production of “Hamilton” combines the best elements of live theater, film and streaming to bring the cultural phenomenon to homes around the world for a thrilling, once-in-a-lifetime experience. OFFICIAL BOILERPLATE: An unforgettable cinematic stage performance, the filmed version of the original Broadway production of “Hamilton” combines the best elements of live theater, film and streaming to bring the cultural phenomenon to homes around the world for a thrilling, once-in-a-lifetime experience. “Hamilton” is the story of America then, told by America now. Featuring a score that blends hip-hop, jazz, R&B and Broadway, “Hamilton” has taken the story of American founding father Alexander Hamilton and created a revolutionary moment in theatre—a musical that has had a profound impact on culture, politics, and education. Filmed at The Richard Rodgers Theatre on Broadway in June of 2016, the film transports its audience into the world of the Broadway show in a uniquely intimate way. With book, music, and lyrics by Lin-Manuel Miranda and direction by Thomas Kail, “Hamilton” is inspired by the book “Alexander Hamilton” by Ron Chernow and produced by Thomas Kail, Lin-Manuel Miranda and Jeffrey Seller, with Sander Jacobs and Jill Furman serving as executive producers. The 11-time-Tony Award®-, GRAMMY Award®-, Olivier Award- and Pulitzer Prize-winning stage musical stars: Daveed Diggs as Marquis de Lafayette/Thomas Jefferson; Renée Elise Goldsberry as Angelica Schuyler; Jonathan Groff as King George; Christopher Jackson as George Washington; Jasmine Cephas Jones as Peggy Schuyler/Maria Reynolds; Lin-Manuel Miranda as Alexander Hamilton; Leslie Odom, Jr. -

Bullseye with Jesse Thorn Is a Production of Maximumfun.Org and Is Distributed by NPR

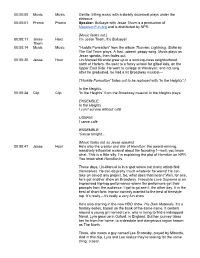

00:00:00 Music Music Gentle, trilling music with a steady drumbeat plays under the dialogue. 00:00:01 Promo Promo Speaker: Bullseye with Jesse Thorn is a production of MaximumFun.org and is distributed by NPR. [Music fades out.] 00:00:11 Jesse Host I’m Jesse Thorn. It’s Bullseye! Thorn 00:00:14 Music Music “Huddle Formation” from the album Thunder, Lightning, Strike by The Go! Team plays. A fast, upbeat, peppy song. Music plays as Jesse speaks, then fades out. 00:00:20 Jesse Host Lin-Manuel Miranda grew up in a working-class neighborhood, north of Harlem. He went to a fancy school for gifted kids, on the Upper East Side. He went to college at Wesleyan, and not long after he graduated, he had a hit Broadway musical— [“Huddle Formation” fades out to be replaced with “In the Heights”.] In the Heights. 00:00:34 Clip Clip “In the Heights” from the Broadway musical In the Heights plays. ENSEMBLE: In the Heights I can’t survive without café USNAVI: I serve café ENSEMBLE: 'Cause tonight... [Music fades out as Jesse speaks] 00:00:41 Jesse Host He’s also the creator and star of Hamilton: the award-winning, massively influential musical about the founding f—well, you know what. This is a little silly. I’m explaining the plot of Hamilton on NPR. You know what Hamilton is. These days, Lin-Manuel is in a spot where not many artists find themselves. He can do pretty much whatever he wants! He can take on almost any project. -

Edition 2 | 2019-2020

WELCOME FROM THE OFFICE OF THE DIRECTORS elcome to Paper Mill Playhouse and to Rodgers + Hammerstein’s Cinderella. We’ve worked magic to bring you this delightful musical fairy tale complete Wwith dance, romance, laughs, and timeless tunes. Our fabulously talented cast features favorite Paper Mill alumni alongside some of the brightest newcomers; the design team is first-class; and Mark S. Hoebee is back in the director’s chair, thrilled as always to collaborate with choreographer JoAnn M. Hunter and music director Michael Borth. It’s not too late to secure your seats for the rest of our exciting 2019–2020 season by becoming a subscriber. Up next, we are proud to produce the world premiere of Unmasked: The Music of Andrew Lloyd Webber, celebrating the most prolific Broadway composer of our day. Then, the “divine” comedy smash Sister Act ushers in the spring and is guaranteed to make you sing praises. We close with The Wanderer, another world premiere, based on the life and music of rock and roll sensation Dion. It’s already selling like gangbusters, so don’t miss out. Subscribers should have received our “State of the Theater” newsletter, which highlights many of the accomplishments of the past year and demonstrates Paper Mill’s far-reaching impact across the state of New Jersey and around the world. You may also view it online at PaperMill.org/stateofthetheater. Paper Mill is stronger than ever, with great thanks to you, our audience, donors, and funders. And before the clock ticks down on another year, we hope you will renew your support or consider becoming a Member with a tax-deductible contribution (read more below). -

Rap in the Context of African-American Cultural Memory Levern G

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 Empowerment and Enslavement: Rap in the Context of African-American Cultural Memory Levern G. Rollins-Haynes Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES EMPOWERMENT AND ENSLAVEMENT: RAP IN THE CONTEXT OF AFRICAN-AMERICAN CULTURAL MEMORY By LEVERN G. ROLLINS-HAYNES A Dissertation submitted to the Interdisciplinary Program in the Humanities (IPH) in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Levern G. Rollins- Haynes defended on June 16, 2006 _____________________________________ Charles Brewer Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________________________ Xiuwen Liu Outside Committee Member _____________________________________ Maricarmen Martinez Committee Member _____________________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member Approved: __________________________________________ David Johnson, Chair, Humanities Department __________________________________________ Joseph Travis, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii This dissertation is dedicated to my husband, Keith; my mother, Richardine; and my belated sister, Deloris. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Very special thanks and love to -

Groundhog Day

GROUNDHOG DAY TEACHING RESOURCES JUL—S E P 2 016 CONTENTS Company 3 Old Vic New Voices Education The Old Vic The Cut Creative team 7 London SE1 8NB Character breakdown 10 E [email protected] @oldvicnewvoices Synopsis 12 © The Old Vic, 2016. All information is correct at the Themes 15 time of going to press, but may be subject to change Timeline – Musicals adapted from American and 16 Teaching resources European films Compiled by Anne Langford Design Matt Lane-Dixon Rehearsal and production Interview with illusionist and Old Vic Associate, Paul Kieve 18 photography Manuel Harlan Interview with David Birch and Carolyn Maitland, 24 Old Vic New Voices Alexander Ferris Director Groundhog Day cast members Sharon Kanolik Head of Education & Community From Screen to Stage: Considerations when adapting films to 28 Ross Crosby Community Co-ordinator stage musicals Richard Knowles Stage Business Co-ordinator A conversation with Harry Blake about songs for musicals and 30 Tom Wright Old Vic New Voices Intern plays with songs and the differences between them. Further details of this production oldvictheatre.com Practical exercises – Screen to stage 33 A day in the life of Danny Krohm, Front of House Manager 37 Bibliography and further reading 39 The Old Vic Groundhog Day teaching resource 2 COMPANY Leo Andrew David Birch Ste Clough Roger Dipper Georgina Hagen Kieran Jae Julie Jupp Andy Karl Ensemble Ensemble Ensemble Ensemble Ensemble Ensemble Ensemble Phil Connors (Jenson) (Chubby Man) (Jeff) (Deputy) (Nancy) (Fred) (Mrs Lancaster) AndrewLangtree -

Mild Weather Aids Work

THE VOLUME 128,COSMOS ISSUE 12 FRIDAY, DECEMBER 2, 2016 CEDAR RAPIDS, IOWA MILD WEATHER AIDS WORK Construction continues on Eby Fieldhouse Dec. 1. Executive Vice President Michael White said College Drive will not close until the week of Dec. 19. Continued on pg. 2. INSIDE THE COSMOS NEWS 2 FEATURES 5 DIVERSIONS 6 THE WINTER READ THEATER DIVERSITY VOLLEYBALL FINALS P. 3 P. 4 P. 6 INDEX 2News Friday, December 2, 2016 Construction continues on Eby THE COSMOS into the current weight Eby, White said, Hickok Lisa McDonald room and Clark Racquet 2016-2017 STAFF Editor-in-chief renovations are almost Center. However, White fully complete. The last Thanks to build- said, further relocation major planned addition EDITOR-IN-CHIEF ing-friendly weather, of the equipment will be Lisa McDonald to Hickok is the elevator, a lot of headway has necessary since the cur- and delays with the ele- been made on the Eby rent weight room is also vator firm currently have COPY EDITORS slotted to be turned into Lisa McDonald Fieldhouse construction, the installation occurring additional locker room Rachel Deyoe Executive Vice President in January 2017. Michael White said. space. "You'll still be able "The floors are almost "There is going to be to get to the new class- ASSISTANT LAYOUT probably a stretch here EDITORS all in," White said, "with rooms and everything," Allison Bartnick the exception of the area where the weight room White said, since virtu- Rachel Deyoe to the south, where the will be relocated and ally all the work will be Mai Fukuhara new strength and condi- they'll have some weights contained in the elevator tioning room will be." in various areas," White shaft and in the elevator PHOTOGRAPHERS White said once the said. -

Policeman Files Suit Against Westfield and Former Chief by PAUL J

Ad Populos, Non Aditus, Pervenimus Published Every Thursday Since September 3, 1890 (908) 232-4407 USPS 680020 Thursday, December 1, 2005 OUR 115th YEAR – ISSUE NO. 48-2005 Periodical – Postage Paid at Westfield, N.J. www.goleader.com [email protected] SIXTY CENTS Policeman Files Suit Against Westfield and Former Chief By PAUL J. PEYTON department computers to conduct ille- contacted Officer Kasko about the Specially Written for The Westfield Leader gal background checks in 2004 on alleged illegal background checks. WESTFIELD – A Westfield police several town residents and alleged re- Officer Kasko questioned officers on officer has filed a lawsuit against the taliation the officer faced when he whether they knew of inappropriate town on allegations that he was ha- attempted to look into the validity of use of the police computer systems to rassed and retaliated against after he the illegal background checks. run criminal histories of any town reported information to town offi- “During a telephone conversation residents. cials per the town’s “whistle blower” with the editor of a local Westfield Upon learning of Officer Kasko’s policy. newspaper (The Westfield Leader), inquiries, Chief Tracy ordered a de- Officer Gregory Kasko filed a law- Chief Tracy advised the editor that he tailed report from Officer Kasko ex- suit on November 14 in U.S. District maintained files on certain Westfield plaining “why (the) plaintiff had not Court in Newark, a suit assigned to residents, which contained illegal personally advised him (Chief Tracy) Judge William Martini. The three- criminal background checks that he of the matter,” the suit charges. -

Lin-Manuel Miranda Quiara Alegría Hudes

Artistic Director Nathaniel Shaw Managing Director Phil Whiteway PREMIER SPONSOR PRODUCTION SPONSOR MUSIC AND LYRICS BY BOOK BY LIN-MANUEL QUIARA MIRANDA ALEGRÍA HUDES CONCEIVED BY SEASON SPONSORS LIN-MANUEL MIRANDA Development of In The Heights was supported by the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center during a residency at the Music Theater Conference of 2005. Initially developed by Back House Productions. Originally Produced on Broadway by Kevin McCollum, Jeffrey Seller, Jill Furman Willis,Sander Jacobs, Goodman/Grossman, Peter Fine, Everett/Skipper E. Rhodes and Leona B. IN THE HEIGHTS is presented through special arrangement Carpenter Foundation with R & H Theatricals: www.rnh.com STAGE MANAGEMENT SOUND DESIGN Christi B. Spann* Derek Dumais COSTUME DESIGN LIGHT DESIGN SET DESIGN Sarah Grady Joe Doran+ Anna Louizos+ MUSIC DIRECTION CHOREOGRAPHY Ben Miller Karla Garcia DIRECTION Nathaniel Shaw^ SARA BELLE AND NEIL NOVEMBER THEATRE | MARJORIE ARENSTEIN STAGE CAST MUSICAL NUMBERS AND SCENES Usnavi ...............................................................JJ Caruncho* ACT I Vanessa ............................................................ Arielle Jacobs* In The Heights ................................................... Usnavi, Company Nina ................................................................. Shea Gomez Breathe ........................................................... Nina, Company Benny ................................................................. Josh Marin* Benny’s Dispatch .....................................................