Billy Griffiths an Aboriginal History of the University Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Incubation at Saqqâra1 Gil H

Proceedings of the Twenty-Fifth International Congress of Papyrology, Ann Arbor 2007 American Studies in Papyrology (Ann Arbor 2010) 649–662 Incubation at Saqqâra1 Gil H. Renberg Few sites in the Greco-Roman world provide a more richly varied set of documents attesting to the importance of dreams in personal religion than the cluster of religious complexes situated on the Saqqâra bluff west of Memphis.2 The area consists primarily of temples and sacred animal necropoleis linked to several cults, most notably the famous Sarapeum complex,3 and has produced inscriptions, papyri and ostraka that cite or even recount dreams received by various individuals, while literary sources preserved on papyrus likewise contain descriptions of god-sent dreams received there.4 The abundant evidence for dreams and dreamers at Saqqâra, as well as the evidence for at least one conventional oracle at the site,5 has led to the understandable assumption that incubation was commonly practiced there.6 However, 1 Acknowledgements: In addition to those who attended the presentation of this paper at the Congress of Papyrology, I would like to thank Dorothy J. Thompson and Richard Jasnow for sharing their insights on this subject. 2 The subject discussed in this article will be dealt with more fully in a book now in preparation, tentatively entitled Where Dreams May Come: Incubation Sanctuaries in the Greco-Roman World. 3 On Saqqâra and its religious life, see especially UPZ I, pp. 7–95 and Thompson 1988 (with references to earlier studies); cf. LexÄg V.3 (1983) 412–428. For the sacred animal necropoleis, see the various volumes of the Egyptian Exploration Society cited below, as well as Kessler 1989, 56–150 and Davies and Smith 1997. -

Eclectic Antiquity Catalog

Eclectic Antiquity the Classical Collection of the Snite Museum of Art Compiled and edited by Robin F. Rhodes Eclectic Antiquity the Classical Collection of the Snite Museum of Art Compiled and edited by Robin F. Rhodes © University of Notre Dame, 2010. All Rights Reserved ISBN 978-0-9753984-2-5 Table of Contents Introduction..................................................................................................................................... 1 Geometric Horse Figurine ............................................................................................................. 5 Horse Bit with Sphinx Cheek Plates.............................................................................................. 11 Cup-skyphos with Women Harvesting Fruit.................................................................................. 17 Terracotta Lekythos....................................................................................................................... 23 Marble Lekythos Gravemarker Depicting “Leave Taking” ......................................................... 29 South Daunian Funnel Krater....................................................................................................... 35 Female Figurines.......................................................................................................................... 41 Hooded Male Portrait................................................................................................................... 47 Small Female Head...................................................................................................................... -

Re-Awakening Languages: Theory and Practice in the Revitalisation Of

RE-AWAKENING LANGUAGES Theory and practice in the revitalisation of Australia’s Indigenous languages Edited by John Hobson, Kevin Lowe, Susan Poetsch and Michael Walsh Copyright Published 2010 by Sydney University Press SYDNEY UNIVERSITY PRESS University of Sydney Library sydney.edu.au/sup © John Hobson, Kevin Lowe, Susan Poetsch & Michael Walsh 2010 © Individual contributors 2010 © Sydney University Press 2010 Reproduction and Communication for other purposes Except as permitted under the Act, no part of this edition may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or communicated in any form or by any means without prior written permission. All requests for reproduction or communication should be made to Sydney University Press at the address below: Sydney University Press Fisher Library F03 University of Sydney NSW 2006 AUSTRALIA Email: [email protected] Readers are advised that protocols can exist in Indigenous Australian communities against speaking names and displaying images of the deceased. Please check with local Indigenous Elders before using this publication in their communities. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Re-awakening languages: theory and practice in the revitalisation of Australia’s Indigenous languages / edited by John Hobson … [et al.] ISBN: 9781920899554 (pbk.) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Aboriginal Australians--Languages--Revival. Australian languages--Social aspects. Language obsolescence--Australia. Language revival--Australia. iv Copyright Language planning--Australia. Other Authors/Contributors: Hobson, John Robert, 1958- Lowe, Kevin Connolly, 1952- Poetsch, Susan Patricia, 1966- Walsh, Michael James, 1948- Dewey Number: 499.15 Cover image: ‘Wiradjuri Water Symbols 1’, drawing by Lynette Riley. Water symbols represent a foundation requirement for all to be sustainable in their environment. -

2013 NSW Museum & Gallery Sector Census and Survey

2013 NSW Museum & Gallery Sector Census and Survey 43-51 Cowper Wharf Road September 2013 Woolloomooloo NSW 2011 w: www.mgnsw.org.au t: 61 2 9358 1760 Introduction • This report is presented in two parts: The 2013 NSW Museum & Gallery Sector Census and the 2013 NSW Small to Medium Museum & Gallery Survey. • The data for both studies was collected in the period February to May 2013. • This report presents the first comprehensive survey of the small to medium museum & gallery sector undertaken by Museums & Galleries NSW since 2008 • It is also the first comprehensive census of the museum & gallery sector undertaken since 1999. Images used by permission. Cover images L to R Glasshouse, Port Macquarie; Eden Killer Whale Museum , Eden; Australian Fossil and Mineral Museum, Bathurst; Lighting Ridge Museum Lightning Ridge; Hawkesbury Gallery, Windsor; Newcastle Museum , Newcastle; Bathurst Regional Gallery, Bathurst; Campbelltown arts Centre, Campbelltown, Armidale Aboriginal Keeping place and Cultural Centre, Armidale; Australian Centre for Photography, Paddington; Australian Country Music Hall of Fame, Tamworth; Powerhouse Museum, Tamworth 2 Table of contents Background 5 Objectives 6 Methodology 7 Definitions 9 2013 Museums and Gallery Sector Census Background 13 Results 15 Catergorisation by Practice 17 2013 Small to Medium Museums & Gallery Sector Survey Executive Summary 21 Results 27 Conclusions 75 Appendices 81 3 Acknowledgements Museums & Galleries NSW (M&G NSW) would like to acknowledge and thank: • The organisations and individuals -

Faculty of Law Handbook 1995 Faculty of Law Handbook 1995 ©The University of Sydney 1994 ISSN 1034-2656

The University of Sydney Faculty of Law Handbook 1995 Faculty of Law Handbook 1995 ©The University of Sydney 1994 ISSN 1034-2656 The address of the Law School is: The University of Sydney Law School 173-5 Phillip Street Sydney, N.S.W. 2000 Telephone (02) 232 5944 Document Exchange No: DX 983 Facsimile: (02) 221 5635 The address of the University is: The University of Sydney N.S.W. 2006 Telephone 351 2222 Setin 10 on 11.5 Palatino by the Publications Unit, The University of Sydney and printed in Australia by Printing Headquarters, Sydney. Text printed on 80gsm recycled bond, using recycled milk cartons. Welcome from the Dean iv Location of the Law School vi How to use the handbook vii 1. Staff 1 2. History of the Faculty of Law 3 3. Law courses 4 4. Undergraduate degree requirements 7 Resolutions of the Senate and the Faculty 7 5. Courses of study 12 6. Guide for law students and other Faculty information 24 The Law School Building 24 Guide for law students 24 Other Faculty information 29 Law Library 29 Sydney Law School Foundation 30 Sydney Law Review 30 Australian Centre for Environmental Law 30 Institute of Criminology 31 Centre for Plain Legal Language 31 Centre for Asian and Pacific Law 31 Faculty societies and student representation 32 Semester and vacation dates 33 The Allen Allen and Hemsley Visiting Fellowship 33 Undergraduate scholarships and prizes 34 7. Employment 36 Main Campus map 39 The legal profession in each jurisdiction was almost entirely self-regulating (and there was no doubt it was a profession, and not a mere 'occupation' or 'service industry'). -

A Life of Thinking the Andersonian Tradition in Australian Philosophy a Chronological Bibliography

own. One of these, of the University Archive collections of Anderson material (2006) owes to the unstinting co-operation of of Archives staff: Julia Mant, Nyree Morrison, Tim Robinson and Anne Picot. I have further added material from other sources: bibliographical A Life of Thinking notes (most especially, James Franklin’s 2003 Corrupting the The Andersonian Tradition in Australian Philosophy Youth), internet searches, and compilations of Andersonian material such as may be found in Heraclitus, the pre-Heraclitus a chronological bibliography Libertarian Broadsheet, the post-Heraclitus Sydney Realist, and Mark Weblin’s JA and The Northern Line. The attempt to chronologically line up Anderson’s own work against the work of James Packer others showing some greater or lesser interest in it, seems to me a necessary move to contextualise not only Anderson himself, but Australian philosophy and politics in the twentieth century and beyond—and perhaps, more broadly still, a realist tradition that Australia now exports to the world. Introductory Note What are the origins and substance of this “realist tradition”? Perhaps the best summary of it is to be found in Anderson’s own The first comprehensive Anderson bibliography was the one reading, currently represented in the books in Anderson’s library constructed for Studies in Empirical Philosophy (1962). It listed as bequeathed to the University of Sydney. I supply an edited but Anderson’s published philsophical work and a fair representation unabridged version of the list of these books that appears on the of his published social criticism. In 1984 Geraldine Suter published John Anderson SETIS website, to follow the bibliography proper. -

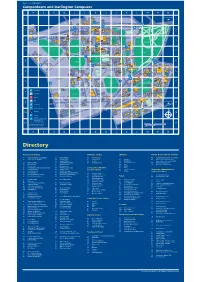

Camperdown and Darlington Campuses

Map Code: 0102_MAIN Camperdown and Darlington Campuses A BCDEFGHJKLMNO To Central Station Margaret 1 ARUNDEL STREETTelfer Laurel Tree 1 Building House ROSS STREETNo.1-3 KERRIDGE PLACE Ross Mackie ARUNDEL STREET WAY Street Selle Building BROAD House ROAD Footbridge UNIVERSITY PARRAMATTA AVENUE GATE LARKIN Theatre Edgeworth Botany LANE Baxter's 2 David Lawn Lodge 2 Medical Building Macleay Building Foundation J.R.A. McMillan STREET ROSS STREET Heydon-Laurence Holme Building Fisher Tennis Building Building GOSPER GATE AVENUE SPARKES Building Cottage Courts STREET R.D. Watt ROAD Great Hall Ross St. Building Building SCIENCE W Gate- LN AGRICULTURE EL Bank E O Information keepers S RUSSELL PLACE R McMaster Building P T Centre UNIVERSITY H Lodge Building J.D. E A R Wallace S Badham N I N Stewart AV Pharmacy E X S N Theatre Building E U ITI TUNN E Building V A Building S Round I E C R The H Evelyn D N 3 OO House ROAD 3 D L L O Quadrangle C A PLAC Williams Veterinary John Woolley S RE T King George VI GRAFF N EK N ERSITY Building Science E Building I LA ROA K TECHNOLOGY LANE N M Swimming Pool Conference I L E I Fisher G Brennan MacCallum F Griffith Taylor UNIV E Centre W Library R Building Building McMaster Annexe MacLaurin BARF University Oval MANNING ROAD Hall CITY R.M.C. Gunn No.2 Building Education St. John's Oval Old Building G ROAD Fisher Teachers' MANNIN Stack 4 College Manning 4 House Manning Education Squash Anderson Stuart Victoria Park H.K. -

ITER: the Way for Australian Energy Research?

The University of Sydney School of Physics 6 0 0 ITER: the Way for Australian 2 Energy Research? Physics Alumnus talks up the Future of Fusion November “World Energy demand will Amongst the many different energy sources double in the next 50 years on our planet, Dr Green calls nuclear fusion the – which is frightening,” ‘philosopher’s stone of energy’ – an energy source s a i d D r B a r r y G r e e n , that could potentially do everything we want. School of Physics alumnus Appropriate fuel is abundant, with the hydrogen and Research Program isotope deuterium and the element lithium able to Officer, Fusion Association be derived primarily from seawater (as an indication, Agreements, Directorate- the deuterium in 45 litres water and the lithium General for Research at the in one laptop battery would supply the fuel for European Commisison in one person’s personal electricity use for 30 years). Brussels, at a recent School Fusion has ‘little environmental impact or safety research seminar. concerns’: there are no greenhouse gas emissions, “The availability of and unlike nuclear fission there are no runaway cheap energy sources is a nuclear processes. The fusion reactions produce no thing of the past, and we radioactive ash waste, though a fusion energy plant’s Artists’s impression of the ITER fusion reactor have to be concerned about structure would become radioactive – Dr Green the environmental impacts reckoned that the material could be processed and of energy production.” recycled within around 100 years. Dr Green was speaking in Sydney during his nation-wide tour to promote ITER, the massive Despite all these benefits, international research collaboration to build a fusion-energy future is still a long an experimental device to demonstrate the way off. -

SYDNEY ALUMNI Magazine

SYDNEY ALUMNI Magazine 11 14 16 34 NEWS: Calling Dubai-based alumni FEATURE: Hazards for youth PROFILE: Jack Manning Bancroft SPORT: Rowing to Beijing features Spring 2007 4 EDITORIAL Goodbye Dominic, hello Diana 5 FOR THE RECORD What the Chancellor said 9 CELEBRATION AND INNOVATION Cutting edge science, technology, culture and entertainment combine for GerMANY Innovations 18 COVER STORY Editor Diana Simmonds Mural maker Pierre Mol explains the how and why The University of Sydney, Publications Office of his historic artwork Room K6.06, Quadrangle A14, NSW 2006 Telephone +61 2 9036 6372 Fax +61 2 9351 6868 36 TREASURE Email [email protected] The Macleays inspired artist Robyn Stacey and Sub-editor John Warburton writer Ashley Hay Design tania edwards design Contributors Professor John Bennett, Vice-Chancellor regulars Professor Gavin Brown, HE Professor Marie Bashir AC CVO, Graham Croker, Sarah Duke, Ashley Hay, Marie Jacobs, 2 LETTERS Helen Mackenzie, Fran Molloy, Heidi Mortlock, Maggie Astrology predictably on the nose Renvoize, Ted Sealy, Robyn Stacey, Melissa Sweet. Printed by PMP Limited 8 OPINION Excellence must be pursued, writes Vice-Chancellor Cover photo Pierre Mol with his mural at The Rocks, Sydney. Professor Gavin Brown Photograph by Fran Molloy. 28 DIARY Advertising Please direct all inquiries to the editor. So much to do, so little time Editorial Advisory Committee The Sydney Alumni Magazine is supported by an Editorial 30 GRAPEVINE Advisory Committee. Its members are: Kathy Bail, editor, From the 1940s to the present; who is doing what Australian Financial Review magazine; David Marr (LLB ’71), Sydney Morning Herald; William Fraser, editor ACP Magazines; Martin Hoffman (BEcon ’86), consultant, Andrew Potter, Media Manager, University of Sydney; Helen Trinca, editor, Weekend Australian magazine. -

5-7 December, Sydney, Australia

IRUG 13 5-7 December, Sydney, Australia 25 Years Supporting Cultural Heritage Science This conference is proudly funded by the NSW Government in association with ThermoFisher Scientific; Renishaw PLC; Sydney Analytical Vibrational Spectroscopy Core Research Facility, The University of Sydney; Agilent Technologies Australia Pty Ltd; Bruker Pty Ltd, Perkin Elmer Life and Analytical Sciences; and the John Morris Group. Conference Committee • Paula Dredge, Conference Convenor, Art Gallery of NSW • Suzanne Lomax, National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA • Boris Pretzel, (IRUG Chair for Europe & Africa), Victoria and Albert Museum, London • Beth Price, (IRUG Chair for North & South America), Philadelphia Museum of Art Scientific Review Committee • Marcello Picollo, (IRUG chair for Asia, Australia & Oceania) Institute of Applied Physics “Nello Carrara” Sesto Fiorentino, Italy • Danilo Bersani, University of Parma, Parma, Italy • Elizabeth Carter, Sydney Analytical, The University of Sydney, Australia • Silvia Centeno, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA • Wim Fremout, Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage, Brussels, Belgium • Suzanne de Grout, Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands, Amsterdam, The Netherlands • Kate Helwig, Canadian Conservation Institute, Ottawa, Canada • Suzanne Lomax, National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA • Richard Newman, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA • Gillian Osmond, Queensland Art Gallery|Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, Australia • Catherine Patterson, Getty Conservation Institute, Los Angeles, USA -

Disorder with Law: Determining the Geographical Indication for the Coonawarra Wine Region

Gary Edmond* DISORDER WITH LAW: DETERMINING THE GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATION FOR THE COONAWARRA WINE REGION Coonawarra, historic, if much-disputed, wine region in South Australia’s Limestone Coast Zone and the most popularly revered wine region in AUSTRALIA for Cabernet Sauvignon, grown on its famous strip of TERRA ROSSA soil. Jancis Robinson (ed), The Oxford Companion to Wine (2nd ed, 1999). I. INTRODUCTION his empirical study follows a protracted dispute over one of Australia’s premier wine regions. Surveying the introduction of a regulatory scheme in a small rural community it demonstrates the potentially disruptive impact of law and explores some of the limitations of legal and Tregulatory processes.1 In this instance, the domestic ramifications of an international trade agreement between Australia and Europe generated frustration, animosity and eventually litigation. Attempts to repair the situation through ordinary legal mechanisms seem to have merely superimposed considerable * BA(Hons) University of Wollongong, LLB(Hons) University of Sydney, PhD University of Cambridge. Faculty of Law, The University of New South Wales, Sydney 2052, [email protected]. This project was made possible by a Goldstar Award in conjunction with a Faculty Research Grant. The author would like to thank the many people who gave generously of their time, opinions and materials. I am particularly appreciative of contributions from: Doug Balnaves, Joy Bowen, Lita and Tony Brady, Johan Bruwer, Sue and W.G. Butler, Pat and Des Castine, Andrew Childs, Peter Copping, -

Dance of the Nomad: a Study of the Selected Notebooks of A.D.Hope

DANCE OF THE NOMAD DANCE OF THE NOMAD A Study of the Selected Notebooks of A. D. Hope ANN McCULLOCH Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/dance_nomad _citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Entry Author: McCulloch, A. M. (Ann Maree), 1949- Title: Dance of the nomad : a study of the selected notebooks of A.D. Hope / Ann McCulloch. ISBN: 9781921666902 (pbk.) 9781921666919 (eBook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Hope, A. D. (Alec Derwent), 1907-2000--Criticism and interpretation. Hope, A. D. (Alec Derwent), 1907-2000--Notebooks, sketchbooks, etc. Dewey Number: A828.3 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or trans- mitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Emily Brissenden Cover: Professor A. D. Hope. 1991. L. Seselja. NL36907. By permission of National Library of Australia. Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2010 ANU E Press First edition © 2005 Pandanus Books In memory of my parents Ann and Kevin McDermott and sister in law, Dina McDermott LETTER TO ANN McCULLOCH ‘This may well be rym doggerel’, dear Ann But the best I can manage in liquor so late At night. You asked me where I’d begin in your place. I can Not answer that. But as a general case I might. Drop the proviso, ‘Supposing That I were you’; I find it impossible to think myself in your place But in general almost any writer would do: The problem is much the same in every case.