Livelihoods in Crisis: a Longitudinal Study in Pader, Uganda Year Two Update

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mapping a Healthier Future

Health Planning Department, Ministry of Health, Uganda Directorate of Water Development, Ministry of Water and Environment, Uganda Uganda Bureau of Statistics International Livestock Research Institute World Resources Institute The Republic of Uganda Health Planning Department MINISTRY OF HEALTH, UGANDA Directorate of Water Development MINISTRY OF WATER AND ENVIRONMENT, UGANDA Uganda Bureau of Statistics Mapping a Healthier Future ISBN: 978-1-56973-728-6 How Spatial Analysis Can Guide Pro-Poor Water and Sanitation Planning in Uganda HEALTH PLANNING DEPARTMENT MINISTRY OF HEALTH, UGANDA Plot 6 Lourdel Road P.O. Box 7272 AUTHORS AND CONTRIBUTORS Kampala, Uganda http://www.health.go.ug/ This publication was prepared by a core team from fi ve institutions: The Health Planning Department at the Ministry of Health (MoH) leads eff orts to provide strategic support Health Planning Department, Ministry of Health, Uganda to the Health Sector in achieving sector goals and objectives. Specifi cally, the Planning Department guides Paul Luyima sector planning; appraises and monitors programmes and projects; formulates, appraises and monitors Edward Mukooyo national policies and plans; and appraises regional and international policies and plans to advise the sector Didacus Namanya Bambaiha accordingly. Francis Runumi Mwesigye Directorate of Water Development, Ministry of Water and Environment, Uganda DIRECTORATE OF WATER DEVELOPMENT Richard Cong MINISTRY OF WATER AND ENVIRONMENT, UGANDA Plot 21/28 Port Bell Road, Luzira Clara Rudholm P.O. Box 20026 Disan Ssozi Kampala, Uganda Wycliff e Tumwebaze http://www.mwe.go.ug/MoWE/13/Overview Uganda Bureau of Statistics The Directorate of Water Development (DWD) is the lead government agency for the water and sanitation Thomas Emwanu sector under the Ministry of Water and Environment (MWE) with the mandate to promote and ensure the rational and sustainable utilization, development and safeguard of water resources for social and economic Bernard Justus Muhwezi development, as well as for regional and international peace. -

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT AND MONITORING PLAN Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development Rural Electrification Agency ENERGY FOR RURAL TRANSFORMATION PHASE III GRID INTENSIFICATION SCHEMES PACKAGED UNDER WEST NILE, NORTH NORTH WEST, AND NORTHERN SERVICE TERRITORIES Public Disclosure Authorized JUNE, 2019 i LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS CDO Community Development Officer CFP Chance Finds Procedure DEO District Environment Officer ESMP Environmental and Social Management and Monitoring Plan ESMF Environmental Social Management Framework ERT III Energy for Rural Transformation (Phase 3) EHS Environmental Health and Safety EIA Environmental Impact Assessment ESMMP Environmental and Social Mitigation and Management Plan GPS Global Positioning System GRM Grievance Redress Mechanism MEMD Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development NEMA National Environment Management Authority OPD Out Patient Department OSH Occupational Safety and Health PCR Physical Cultural Resources PCU Project Coordination Unit PPE Personal Protective Equipment REA Rural Electrification Agency RoW Right of Way UEDCL Uganda Electricity Distribution Company Limited WENRECO West Nile Rural Electrification Company ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ......................................................... ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................ iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................... -

Uganda Humanitarian Update

UGANDA HUMANITARIAN UPDATE MAY – JUNE 2010 I. HIGHLIGHTS AMID HEAVY RAINS, HUMANITARIAN ACCESS IN PARTS OF KARAMOJA AND TESO HAMPERED BY DETERIORATING ROAD CONDITIONS OVER 1,000 CHOLERA CASES REGISTERED IN KARAMOJA SINCE APRIL 2010 90% OF IDPS IN NORTHERN UGANDA NO LONGER LIVING IN CAMPS, BUT LAND CONFLICTS AND LANDMINES IMPEDING RETURN IN SOME AREAS II. SECURITY AND ACCESS SECURITY The general situation in Karamoja remained fragile, according to the United Nations Department for Safety and Security (UNDSS). Cattle raids, including on protected kraals, particularly affected Moroto and Kotido, with some resulting in fierce clashes between the Uganda People’s Defence Forces and the raiders. In South Karamoja incidents associated with food distributions involved theft of food and non-food items (NFIs), and attacks on food distributors as well as on food recipients. Following three road ambushes in Alerek sub-county of Abim District during the month, UNDSS issued an advisory limiting UN movement along the Abim-Kotido road to between 09.00Hrs and 16.00Hrs with effect from 28 June 2010. Three civilians were killed in one of those ambushes. In northern Uganda, Amuru District officials and partners carried out a joint assessment in the wake of a violent land dispute that occurred in Koli village of Pabbo sub-county on 23 June. Preliminary findings indicated that one person was killed and several others injured in the dispute involving two clans. Some 40 huts were torched and many members of either clan had fled the village. Also of concern in the region during the reporting period were raids by illegally armed Karamojong, particularly in Pader District. -

Country Operations Plan

COUNTRY OPERATIONS PLAN Country: Uganda Planning Year: 2004 2004 Country Operations Plan – Uganda __________________________________________________________________________________________ Part I: Executive - Summary 1.1 Context and Beneficiary Populations UNHCR’s presence in Uganda dates back from the 1960s. Though the earlier arrivals of Rwandan refugees had returned in 1994, the country still hosts 18,500 Rwandans who are residual caseloads of the 1996 repatriation from Tanzania. There are some 5,000 Rwandans who entered Mbarara district of Uganda from Tanzania when the Rwandan refugees were being repatriated from there in 2002. The Government of Uganda has not yet decided their status. The majority of the refugees in the country today are Southern Sudanese hosted in northern Uganda and who number about 172,300 (86%) of the total refugee population of 200,800 as of 28 February 2003. About 8,500 Congolese refugees hosted in the Southwest are from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). There are other smaller groups from Somalia, Ethiopia and Kenya that are also being assisted. Sudanese and Congolese refugees are granted status on a prima facie basis, while the status of others is ascertained through individual refugee status determination. Almost all the refugees fled their respective countries of origin because of the civil war and fear of persecution caused by ethnic rivalries and political differences. The Government of Uganda, continues to host refugees from the neighbouring countries. Refugees who are in designated settlememnts are provided with agricultural lands, tools and seeds with the objective of making them self-sufficient. As a result, refugees in the northern settlements have managed to produce a certain percentage of their food requirements, thereby reducing dependence on the food assistance from WFP. -

Food Security and Livelihoods Assessment Lango Sub-Region

April 2011 Food Security and Livelihoods Assessment Lango Sub-region Uganda ACF USA, Food Security and Livelihoods Assessment, April 2011 Uganda TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive summary ........................................................................................................................................................ 5 1. Background ......................................................................................................................................................... 11 1.1. Purpose of the survey ................................................................................................................................ 11 1.2. Methods of the survey ............................................................................................................................... 12 2. Findings of the survey ......................................................................................................................................... 13 2.1. Demographic information .......................................................................................................................... 13 2.2. Household Dietary diversity and food sources .......................................................................................... 19 2.3. Household expenditures ............................................................................................................................ 25 2.4. Income sources and household assets ...................................................................................................... -

Otuke District Local Government

CALL TO ACTION THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA NUTRITION CHALLENGES/ GAPS CALL FOR ACTION RESPONSIBLE Otuke District Nutrition coordination committee Otuke was also supported to conduct a Food GOVERNANCE AREA OFFICE (DNCC), seven (7) Sub counties and One Security and Nutrition Assessments (FSNA). OTUKE DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT Coordination and Weak coordination mechanisms of Partner mapping required to know who DNFP, CAO Town council trained on multi sectoral nutrition FSNA data was not available previously partnerships: nutrition actions at all levels. is where and doing what. DNCC/SNCC ADVOCACY BRIEF ON STRENGTHENING NUTRITION GOVERNANCE FOR MULTI-SECTORAL RESPONSE implementation for improved nutrition unavailable therefore this first FSNA data will members need to be oriented on their outcomes. be used as a baseline to compare progress roles and responsibilities in achievement of health, nutrition and WASH The district conducted quarterly DNCC meetings Establish joint planning and strategic indicators in subsequent FSNAs. Annual FSNAs and support supervision activities aimed at coordination mechanisms amongst will be conducted to assess annual progress. strengthening the accountability framework for partners in the district to reduce on Multisectoral nutrition actions implemented in The Otuke DNCC has been trained on nutrition duplication of resources and achieve sustainable results Otuke district. governance and supported to use reporting templates and monitoring tools previously Systems capacity Lack of clarity on nutrition sensitive Orientation -

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 Ehealth MONTHLY BULLETIN

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 eHEALTH MONTHLY BULLETIN Welcome to this 1st issue of the eHealth Bulletin, a production 2015 of the WHO Country Office. Disease October November December This monthly bulletin is intended to bridge the gap between the Cholera existing weekly and quarterly bulletins; focus on a one or two disease/event that featured prominently in a given month; pro- Typhoid fever mote data utilization and information sharing. Malaria This issue focuses on cholera, typhoid and malaria during the Source: Health Facility Outpatient Monthly Reports, Month of December 2015. Completeness of monthly reporting DHIS2, MoH for December 2015 was above 90% across all the four regions. Typhoid fever Distribution of Typhoid Fever During the month of December 2015, typhoid cases were reported by nearly all districts. Central region reported the highest number, with Kampala, Wakiso, Mubende and Luweero contributing to the bulk of these numbers. In the north, high numbers were reported by Gulu, Arua and Koti- do. Cholera Outbreaks of cholera were also reported by several districts, across the country. 1 Visit our website www.whouganda.org and follow us on World Health Organization, Uganda @WHOUganda WHO UGANDA eHEALTH BULLETIN February 2016 Typhoid District Cholera Kisoro District 12 Fever Kitgum District 4 169 Abim District 43 Koboko District 26 Adjumani District 5 Kole District Agago District 26 85 Kotido District 347 Alebtong District 1 Kumi District 6 502 Amolatar District 58 Kween District 45 Amudat District 11 Kyankwanzi District -

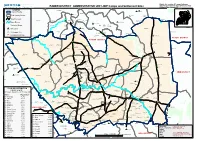

Arcview Print

District, Sub counties, IDP camps, Settlement Sites,Transport Network, Rivers & Protected Areas PADER DISTRICT ADMINISTRATIVE UNIT- IDP Camps and Settlement Sites Reference Date: January 2007 Ayuu Anak Labworoye à LEGENDà à LAYAMO Nam Okora $Z Moyo Koboko Kaabong District Border Yumbe Kitgum Maracha Paibony Adjumani Kotido AMIDA Arua PADER Gulu Abim Amuru Layamo Moroto $Z Nebbi à Oyam Lira Sub County Border Amuria Lapana Buliisa Guda Masindi Apac Dokolo à Kaberamaido Katakwi Nakapiripirit Amolatar à Soroti Kumi Hoima Kapchorwa Nakasonola Bukedea Pallisa Bukwa Nakaseke Kamuli BudakaSironko Kaliro Bududa Bundibugyo Kiboga Kibaale Kayunga ButaleMjabale Namutumba Manafwa Luwero Road Network OROM Kyenjojo Iganga Tororo Kabarole Mubende Jinja Busia Lukwor Bugiri Mityana Mayuge Pawena KITGUM TC Kamwenge Kampala Lumule Kasese Panykel Akwan$Zg à NAMOKORA Sembabule Mpigi Wakiso à Ibanda Mukono à à Lyantonde Bushenyi Kiruhura Major Rivers $ZOmiya-Anyima Masaka Mbarara Kalangala Rukungiri Rakai Kitgum Matidi Kanungu Isingiro Opette $Z Ntungamo Amid$Za à KisoKraobale Protected Areas Lamit tum Lamola àAlel Pàawidi à à à Teso Bar Aparo Hil $Z IDP Camp $ZOryang à PAIMOL Okidài KACHERI à Settlement Site Lagoro àDure Akuna Làab $Z OMIYA- ANYIMA AKWANG Degazzetted Camp Lakwor $ZOmia-Pacha c PALABEK GEM à Laber Bàul KOTIDO DISTRICT KITGUM DISTRICT $ZAcholibur $ZWol $ZPaimol Mutu LAGUTI àLajeng $ZLatanya àLamin Nyi àOkinga ALEREK PALARO ACHOLIBUR Toromàa WOL Lagu$Zti Amilobo Bur Lobo à $ZPorogali Kokil à Ku Ywee à àOtok P/S Amoko à AWACH Awal à à àApil $ZKalongo -

Lira District

National Population and Housing Census 2014 Area Specific Profiles Lira District April 2017 National Population and Housing Census 2014 Area Specific Profiles – Lira District This report presents findings of National Population and Housing Census (NPHC) 2014 undertaken by the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS). Additional information about the Census may be obtained from the UBOS Head Office, Statistics House. Plot 9 Colville Street, P. O. Box 7186, Kampala, Uganda; Telephone: +256-414 706000 Fax: +256-414 237553; E-mail: [email protected]; Website: www.ubos.org Cover Photos: Uganda Bureau of Statistics Recommended Citation Uganda Bureau of Statistics 2017, The National Population and Housing Census 2014 – Area Specific Profile Series, Kampala, Uganda. National Population and Housing Census 2014 Area Specific Profiles – Lira District FOREWORD Demographic and socio-economic data are useful for planning and evidence-based decision making in any country. Such data are collected through Population Censuses, Demographic and Socio-economic Surveys, Civil Registration Systems and other Administrative sources. In Uganda, however, the Population and Housing Census remains the main source of demographic data, especially at the sub-national level. Population Census taking in Uganda dates back to 1911 and since then, the country has undertaken five such Censuses. The most recent, the National Population and Housing Census 2014, was undertaken under the theme ‘Counting for Planning and Improved Service Delivery’. The enumeration for the 2014 Census was conducted in August/September 2014. The Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) worked closely with different Government Ministries, Departments and Agencies (MDAs) as well as Local Governments (LGs) to undertake the census exercise. -

Implementation Status & Results

The World Bank Report No: ISR13907 Implementation Status & Results Uganda Second Northern Uganda Social Action Fund Project (NUSAF2) (P111633) Operation Name: Second Northern Uganda Social Action Fund Project Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 8 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: 03-May-2014 (NUSAF2) (P111633) Public Disclosure Authorized Country: Uganda Approval FY: 2009 Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: AFRICA Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Implementing Agency(ies): Key Dates Public Disclosure Copy Board Approval Date 28-May-2009 Original Closing Date 31-Aug-2014 Planned Mid Term Review Date 30-Jan-2012 Last Archived ISR Date 19-Nov-2013 Effectiveness Date 25-Nov-2009 Revised Closing Date 31-Aug-2014 Actual Mid Term Review Date 14-Jun-2013 Project Development Objectives Project Development Objective (from Project Appraisal Document) To improve access of beneficiary households in Northern Uganda to income earning opportunities and better basic socio-economic services. Has the Project Development Objective been changed since Board Approval of the Project? Yes No Public Disclosure Authorized Component(s) Component Name Component Cost Livelihood Investment Support 60.00 Community Infrastructure Rehabilitation 30.00 Institutional Development 10.00 Overall Ratings Previous Rating Current Rating Progress towards achievement of PDO Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Implementation Progress (IP) Moderately Satisfactory Moderately Satisfactory Public Disclosure Authorized Overall Risk Rating Implementation Status Overview The NUSAF II project originally planned to finance 9750 (i.e. 8000 Household Income Support (HIS), 1000 Public Works (PW) and 750 Community Infrastructure Rehabilitation) sub projects in the five year of its implementation period. As of February 3, 2013 a total of 8,764 subprojects (i.e. -

Monthly Programme Update

EMERGENCY AND HUMANITARIAN ACTION, UGANDA APRIL 200 9 Monthly Programme Update Highlights ♦ Under surge capacity organised by IST/AFRO, supported cholera control in Zimbabwe and VHF training in Zambia. ♦ Continued supporting the second round of Polio supplemental immunization activities continued in northern Uganda, Karamoja and Kamapla with an achievement of over 100 % coverage ♦ Continued supporting Hepatitis E epidemic in Kitgum district ♦ Support to Dokolo district in sleeping sickness control 1. General Situation: Political, Social and Security ♦ Security situation in northern Ugandan districts continued being stable ♦ In Karamoja the security situation remained stable on the roads although raids and other criminal activities continue to be reported in many places of the region. ♦ Disarmament initiated by the government in Karamoja is ongoing 2. Programme Implementation a. Activities Emergency Health, Nutrition and HIV/AIDS Response Project (Sida) In Kitgum District the programme; ♦ Continued to provide technical support towards Hepatitis E interventions to support/ guide sub- county activities including supervision A who staff assists health workers arrange vaccines used for the 2nd round of mass Polio campaigns. of VHTs to enhance community mobilization and public health education. ♦ Finicailly supported VHTs and CBDs with incentives to enable them perform health education/promotion and inspection, establishing completed latrines and tracing for Hepatitis E patients. ♦ Techinically and logistically supported the Polio supplemental immunization. In Gulu and Amuru ♦ Technically and logistically supported Gulu and Amuru districts with the 2nd round of mass Polio campaigns In Pader District, WHO/HAC ♦ Continued to technically support the district health team to coordinate, supervise and monitor Hepatitis E epidemic control interventions by organizing weekly coordination meetings. -

Final Evaluation of the Opportunities for Reducing Adolescent and Child Labor Through Education (ORACLE) Project in Uganda

This page left intentionally blank. Independent Final Evaluation of the Opportunities for Reducing Adolescent and Child Labor Through Education (ORACLE) Project in Uganda International Rescue Committee Cooperative Agreement Number: E-9-K-3-0053 22000077 Funding for this evaluation was provided by the United States Department of Labor under Task Order number DOLQ059622437. Points of view or opinions in this evaluation report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the United States Department of Labor, nor does the mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the United States Government. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY vii I INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 1 II EVALUATION OF ORACLE 5 2.1 Final Evaluation Objectives 5 2.2 Methodology of Final Evaluation 6 2.3 Midterm Evaluation 8 III FINAL EVALUATION: FINDINGS 15 3.1 Program Design 15 3.2 Impact 17 3.3 Project Implementation and Performance 19 3.4 Project Monitoring and Measurement 25 3.5 Project Management 26 3.6 Partnership Coordination and Effectiveness 28 3.7 Sustainability and Replicability 30 IV CONCLUSIONS 35 4.1 Lessons Learned, Best Practices, and Innovations 35 4.2 Recommendations 37 ANNEXES Annex 1: Evaluation Terms of Reference Annex 2: Documents Review Annex 3: Cross Reference of USDOL Questions in TOR pages 5–6 and Answers in the Evaluation Report Annex 4: List of Most Individuals Interviewed and Sites Annex 5: List of Individual Interviews and Focus Group Meetings Conducted With ORACLE Beneficiaries and