Caruso and the Art of Singing, Including Caruso's Vocal Exercises

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

029I-HMVCX1924XXX-0000A0.Pdf

This Catalogue contains all Double-Sided Celebrity Records issued up to and including March 31st, 1924. The Single-Sided Celebrity Records are also included, and will be found under the records of the following artists :-CLARA Burr (all records), CARUSO and MELBA (Duet 054129), CARUSO,TETRAZZINI, AMATO, JOURNET, BADA, JACOBY (Sextet 2-054034), KUBELIK, one record only (3-7966), and TETRAZZINI, one record only (2-033027). International Celebrity Artists ALDA CORSI, A. P. GALLI-CURCI KURZ RUMFORD AMATO CORTOT GALVANY LUNN SAMMARCO ANSSEAU CULP GARRISON MARSH SCHIPA BAKLANOFF DALMORES GIGLI MARTINELLI SCHUMANN-HEINK BARTOLOMASI DE GOGORZA GILLY MCCORMACK Scorn BATTISTINI DE LUCA GLUCK MELBA SEMBRICH BONINSEGNA DE' MURO HEIFETZ MOSCISCA SMIRN6FF BORI DESTINN HEMPEL PADEREWSKI TAMAGNO BRASLAU DRAGONI HISLOP PAOLI TETRAZZINI BI1TT EAMES HOMER PARETO THIBAUD CALVE EDVINA HUGUET PATTt WERRENRATH CARUSO ELMAN JADLOWKER PLANCON WHITEHILL CASAZZA FARRAR JERITZA POLI-RANDACIO WILLIAMS CHALIAPINE FLETA JOHNSON POWELL ZANELLIi CHEMET FLONZALEY JOURNET RACHM.4NINOFF ZIMBALIST CICADA QUARTET KNIIPFER REIMERSROSINGRUFFO CLEMENT FRANZ KREISLER CORSI, E. GADSKI KUBELIK PRICES DOUBLE-SIDED RECORDS. LabelRed Price6!-867'-10-11.,613,616/- (D.A.) 10-inch - - Red (D.B.) 12-inch - - Buff (D.J.) 10-inch - - Buff (D.K.) 12-inch - - Pale Green (D.M.) 12-inch Pale Blue (D.O.) 12-inch White (D.Q.) 12-inch - SINGLE-SIDED RECORDS included in this Catalogue. Red Label 10-inch - - 5'676 12-inch - - Pale Green 12-inch - 10612,615j'- Dark Blue (C. Butt) 12-inch White (Sextet) 12-inch - ALDA, FRANCES, Soprano (Ahl'-dah) New Zealand. She Madame Frances Aida was born at Christchurch, was trained under Opera Comique Paris, Since Marcltesi, and made her debut at the in 1904. -

Time 1925 1930 1935 1940 1945 1950 1955 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010

Giulio Gatti Casazza 1926 Director, Metropolitan Opera Arturo Toscanini Leopold Stokowski 1926 1930 Conductor Conductor Pietro Mascagni Lucrezia Bori James Cæsar Petrillo 1926 1930 1948 Composer Singer Head, American Federation of Musicians Richard Strauss Alfred Hertz Sergei Koussevitsky Helen Traubel Charles Munch 1938 1927 1930 1946 1949 Composer and conductor Conductor Conductor Singer Conductor Ignace J Paderewski Geraldine Farrar Joseph Deems Taylor Marian Anderson Cole Porter 1939 1927 1931 1946 1949 Kirsten Flagstad Pianist, politician Singer Composer, critic Singer Composer 1935 Lauritz Melchior Giulio Gatti-Casazza Ignace Jan Paderewski Yehudi Menuhin Singer Artur Rodziński Gian Carlo Menotti Maria Callas 1940 1923 1928 1932 1947 1950 1956 Artur Rubinstein Edward Johnson Singer Director, Metropolitan Opera Pianist, politician Violinist; 16 years old Conductor Composer Singer 1966 1936 Leopold Stokowski Pianist Johann Sebastian Bach Nellie Melba Mary Garden Lawrence Tibbett Singer Arturo Toscanini Mario Lanza & Enrico Caruso Leonard Bernstein 1940 1968 1927 1930 1933 1948 1951 1957 Jean Sibelius Conductor Dmitri Shostakovich Composer (1685–1750) Singer Singer Singer Conductor Singers Composer, conductor 1937 1942 Beverly Sills Richard Strauss Rosa Ponselle Arturo Toscanini Composer Composer Benjamin Britten Patrice Munsel Renata Tebaldi Rudolf Bing Luciano Pavarotti 1971 1927 1931 1934 1948 1951 1958 1966 1979 Sergei Koussevitsky Sir Thomas Beecham Leontyne Price Singer Georg Solti Composer, conductor Singer Conductor Composer -

Enrico Caruso (1873-1921)

ENRICO CARUSO (1873-1921) Birth Name: Enrico Caruso Place of Birth: Naples, Italy Career Highlights: Enrico Caruso was widely considered the greatest international opera star of his day. He was not American – Caruso was born and died in Naples, Italy – but he spent many years living in New York as a leading star at the Metropolitan Opera, and was the United States’ first recording superstar, issuing almost 300 recordings with the Victor Talking Machine Company (later RCA). While much of his recording focused on operatic works, Caruso recorded many popular songs, including the Neapolitan (southern Italian) song “O Sole Mio,” in the language of his native Naples. (In 1960, Elvis Presley had a No. 1 hit with the song “It’s Now or Never,” sung to same tune as “O Sole Mio.”) In 1918, Caruso recorded the patriotic American World War I song “Over There.” Recording: “O Sole Mio” (traditional Italian song), 1916 Recording: “Over There” (patriotic World War I song), 1918 Questions to consider: What cities are the newspapers below from? What does the size and placement of the articles about Caruso’s death suggest about his popularity in the United States? What are some of the terms used to describe Caruso in the headlines to these articles? Why might American audiences have been interested in listening to recordings of popular Italian songs? What does Caruso’s recording of a song like “Over There” suggest about his attitude toward the United States? About Americans’ attitudes toward him? Why might it have been easier for an Italian to find success as an opera star in the United States during this period than in another field? How might Caruso’s success have helped paved the way for singers of Italian descent who came after him?. -

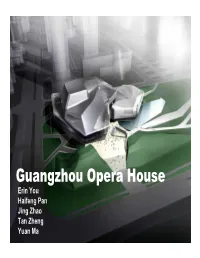

Guangzhou Opera House Erin You Haifeng Pan Jing Zhao Tan Zheng Yuan Ma Overview (Introduction)

Guangzhou Opera House Erin You Haifeng Pan Jing Zhao Tan Zheng Yuan Ma Overview (Introduction) Zaha Hadid’s design won the first prize and was confirmed as the practical one which will become an icon for the Guangzhou City and even accelerate the urbanization of new developing downtown. • Background Information • Design Review • Principle Structure System • Structure Area Division • Interior Space • Auditorium • The Envelope System • Underground Structure and Foundation • Detail • Conclusion Guangzhou Opera House (Background) • The third biggest opera architecture in China • One opera hall (includes main stage, side stage, and back stage) 1,800 seats • One multiple-purpose hall with 400 seats • Foyer, art gallery, restaurant, garage • 70,000 square meters (30,000 square meters underground) • Total construction investment of 200 million dollars The Architect —— Zaha Hadid (Background) • The first woman to win the Pritzker Prize for Architecture • ZAHA HADID has defined a radically new approach to architecture by creating buildings • Multiple perspective points and fragmented geometry to evoke the chaos of modern life. Design Review • Create a new focal point in Guangzhou city • Located downstream of Peal River • Its unique twin boulder design enhances urban function with open access to the riverside and dock areas • Create a new dialogue with the emerging new town • The sheltered area formed in its intersection has been designed to accommodate outdoor activities to complement its primary role as a world stage for the performing arts 0.00 -

Join the National Philharmonic in a Triumphant

West End Off-Broadway United States International Entertainment Log In Re Washington, DC Sections Shows Chat Boards Jobs Students Video Industry Insider Join the National Philharmonic In a Hot Stories BroadwayWorld TV Triumphant Celebration of Poland's 100th Anniversary of Independence Complete Casting Announced for HOW TO by BWW News Desk May. 23, 2018 Tweet Share SUCCEED at the Kennedy Center TV Exclusive: Florida State Universi The National Philharmonic ends its 2017-2018 Southern Heat to Broadway S season at The Music Center at Strathmore with a musical celebration, "100th Anniversary of Poland's Independence," on Saturday, June 2 at 8 p.m. at the Concert Hall at the Music Center at Parris, Breckenridge, & More Strathmore. Conducted by world-renowned Join Drew Gehling in DAVE at Arena Stage Polish Maestro Miroslaw Jacek Baszczyk, the 10 DAYS TO GO CLICK HERE TO V concert will feature music composed by LIVE UPDATE: Poland's greatest musicians, performed by SPONGEBOB SQUAREPANTS or ME some of today's leading vocalists and musicians. for Best Musical... The performance will commence with an introduction by the Ambassador of Poland, Mosaic's Third Season Concludes With Epic World Piotr Wilczek. The 100th anniversary of Poland has signicant meaning for The National Premiere Starring Hadi Philharmonic, which is led by Polish-born Music Director and Conductor Piotr Gajewski. Tabbal One of The National Philharmonic's veteran artists, Brian Ganz-who will perform at the Polish celebration concert-is also a frequent performer of Frédéric Chopin, beginning a quest in 2011 to perform all of the great Polish composer's works. -

The Voice and Singing Sample Pages.Pdf

2 THE VOICE AND SINGING FRANCIS KEEPING AND ROBERTA PRADA Originally LA VOIX ET LE CHANT TRAITÉ PRACTIQUE J. FAURE PARIS 1886 this book, translated and expanded contains Faure’s original exercises with all the transpositions as indicated by the author. 3 Copyright © 2005 Francis Keeping and Roberta Prada. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, except by a newspaper or magazine reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review. Published in 2005 by Vox Mentor LLC. For sales please contact: Vox Mentor LLC. 343 East 30th street, 12M. New York, NY. 10016 phone: 212-684-5485 Email: [email protected] Website: www.voxmentor.biz Printed in USA. Awaiting Library of congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data ISBN 10: 0-9777823-0-1 Originally La Voix et le Chant, J. Faure, Paris, 1886, AU Menestrel, 2 bis, Rue Vivienne, Henri Heugel. The present volume is set in Times New Roman 12 point, on 28 lb. bright white acid free paper and wire bound for easy opening on the music stand. Page turns have been avoided wherever possible in the exercises, meaning that there are intentional blank spaces throughout. The cover photo of J. Faure as a younger man is from the collection of Bill Ecker of Harmonie Autographs, New York City. The present authors have faithfully translated the words of Faure, taking care to preserve the original intent of the author making changes only where necessary to assist modern readers. The music was written using Sibelius 3 and 4™ software. -

Interpreting Tempo and Rubato in Chopin's Music

Interpreting tempo and rubato in Chopin’s music: A matter of tradition or individual style? Li-San Ting A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales School of the Arts and Media Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences June 2013 ABSTRACT The main goal of this thesis is to gain a greater understanding of Chopin performance and interpretation, particularly in relation to tempo and rubato. This thesis is a comparative study between pianists who are associated with the Chopin tradition, primarily the Polish pianists of the early twentieth century, along with French pianists who are connected to Chopin via pedagogical lineage, and several modern pianists playing on period instruments. Through a detailed analysis of tempo and rubato in selected recordings, this thesis will explore the notions of tradition and individuality in Chopin playing, based on principles of pianism and pedagogy that emerge in Chopin’s writings, his composition, and his students’ accounts. Many pianists and teachers assume that a tradition in playing Chopin exists but the basis for this notion is often not made clear. Certain pianists are considered part of the Chopin tradition because of their indirect pedagogical connection to Chopin. I will investigate claims about tradition in Chopin playing in relation to tempo and rubato and highlight similarities and differences in the playing of pianists of the same or different nationality, pedagogical line or era. I will reveal how the literature on Chopin’s principles regarding tempo and rubato relates to any common or unique traits found in selected recordings. -

French Secular Music in Saint-Domingue (1750-1795) Viewed As a Factor in America's Musical Growth. John G

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1971 French Secular Music in Saint-Domingue (1750-1795) Viewed as a Factor in America's Musical Growth. John G. Cale Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Cale, John G., "French Secular Music in Saint-Domingue (1750-1795) Viewed as a Factor in America's Musical Growth." (1971). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2112. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2112 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 72-17,750 CALE, John G., 1922- FRENCH SECULAR MUSIC IN SAINT-DOMINGUE (1750-1795) VIEWED AS A FACTOR IN AMERICA'S MUSICAL GROWTH. The Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College;, Ph.D., 1971 Music I University Microfilms, A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FRENCH SECULAR MUSIC IN SAINT-DOMINGUE (1750-1795) VIEWED AS A FACTOR IN AMERICA'S MUSICAL GROWTH A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The School of Music by John G. Cale B.M., Louisiana State University, 1943 M.A., University of Michigan, 1949 December, 1971 PLEASE NOTE: Some pages may have indistinct print. -

Hemsing Associates, Inc

Hemsing Associates, Inc. 401 East 80th Street, Suite 14H New York, NY 10075-0650 Tel.: 212/772-1132 Fax: 212/628-4255 HEMSING ASSOCIATES Public Relations for the Arts Josephine Hemsing Managing Director Dan Cameron Managing Director Vanessa Meiling Haynes Publicity Associate Ellen Churui Li Publicity Associate Joanna Malinowska Graphics Designer www.hemsingpr.com FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MUSICIANS FOUNDATION TO RECEIVE $25,000 GRANT FROM THE NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS Funds To Be Used To Organize NYC Conference Slated For Fall 2021 To Focus On Performing Artists’ Needs in Time of Crisis June 29, 2020, New York City—The Musicians Foundation is honored to announce that it has been granted a generous Art Works award of $25,000 from the National Endowment for the Arts. Funds are to be used to organize a national conference of organizations that assist professional performing artists in times of need and crisis. The conference, which gains urgency and a new significance in the COVID-19 pandemic, is currently slated to take place in New York City in the fall of 2021 and will address the situation in which performing artists have suffered extreme loss of income as current and future engagements have been cancelled. (Depending on COVID-19 government guidelines, the conference might be postponed till spring 2022.) The conference will be organized by the Musicians Foundation in tandem with a Steering Committee of national and regional organizations, including the Actors Fund, MusiCares, Jazz Foundation, and Episcopal Actors Guild. Founded in 1914 by the Bohemians, a group of musicians and music lovers, the Musicans Foundation was first led by such important figures as Frank Damrosch, Franz Kneisel, Rubin Goldmark (teacher to Aaron Copland and George Gershwin,) and Rudolf Schirmer. -

Lessons for the Vocal Cross-Training Singer and Teacher Lara C

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations Spring 2019 Bel Canto to Punk and Back: Lessons for the Vocal Cross-Training Singer and Teacher Lara C. Wilson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Wilson, L. C.(2019). Bel Canto to Punk and Back: Lessons for the Vocal Cross-Training Singer and Teacher. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5248 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bel Canto to Punk and Back: Lessons for the Vocal Cross-Training Singer and Teacher by Lara C. Wilson Bachelor of Music Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music, 1991 Master of Music Indiana University, 1997 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Performance School of Music University of South Carolina 2019 Accepted by: E. Jacob Will, Major Professor J. Daniel Jenkins, Committee Member Lynn Kompass, Committee Member Janet Hopkins, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Lara C. Wilson, 2019 All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION To my family, David, Dawn and Lennon Hunt, who have given their constant support and unconditional love. To my Mom, Frances Wilson, who has encouraged me through this challenge, among many, always believing in me. Lastly and most importantly, to my husband Andy Hunt, my greatest fan, who believes in me more sometimes than I believe in myself and whose backing has been unwavering. -

The University of Missouri/Columbia

BEAUTIFUL CHORAL TONE QUALITY REHEARSAL TECHNIQUES OF A SUCCESSFUL HIGH SCHOOL CHORAL DIRECTOR A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School University of Missouri-Columbia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by BONNIE L. JENKINS Dr. Wendy Sims, Dissertation Supervisor DECEMBER 2005 © Copyright by Bonnie L. Jenkins 2005 All Rights Reserved APPROVAL PAGE The undersigned, appointed by the Dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled BEAUTIFUL CHORAL TONE QUALITY: REHEARSAL TECHNIQUES OF A SUCCESSFUL HIGH SCHOOL CHORAL DIRECTOR Presented by Bonnie L. Jenkins A candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy And hereby certify that in their opinion it is worthy of acceptance. Dedication This project is dedicated to my loving mother, Charlotte L. Mitchell She passed away one year ago and had so wanted to see me reach this goal. My mother not only supported and encouraged me but she inspired me to work hard to see my goals fulfilled. Acknowledgements The author wishes to express deep appreciation to the following individuals: • To Dr. Wendy Sims for her support, encouragement, expert teaching, and guidance of my program and project. • To Dr. Martin Bergee, Prof. Anne Harrell, and Dr. Jay Scribner for their additional support, encouragement, and excellent teaching. • To my husband, Doug, who has not only encouraged and supported but has sacrificed and helped care for the family through this entire process. • To my two beautiful children, Deja and Mitchell, who have loved, supported, and also sacrificed to help me fulfill this goal. • To my father, Leon Mitchell, the rest of my family, and friends who have given love, encouragement, and support. -

Mascagni E Il Teatro Goldoni: Un Binomio Indissolubile

Mascagni e il Teatro Goldoni: un binomio indissolubile di Alberto Paloscia, Direttore artistico stagione lirica Fondazione Teatro della Città di Livorno “Carlo Goldoni” INTERVENTI Un’altra immagine positore, dopo gli anni di oscura gavetta del giovane Pietro Mascagni prima come direttore di una compagnia girovaga di operette e successivamente come animatore della vita musicale della provincia pugliese nelle veste di fonda- tore e responsabile della Filarmonica di Cerignola, abbatteva le quinte e i fondali del melodramma un po’ imbalsamato del XIX secolo e fondava, con il crudo ed ele- mentare realismo mediterraneo ereditato da Verga, un nuovo stile operistico: quello del verismo e della “Giovine Scuola Italia- na” a cui si sarebbero affiliati, di lì a poco, i nuovi ‘campioni’ del teatro musicale italia- Mascagni e il Teatro Goldoni Teatro il e Mascagni no: Leoncavallo, Puccini, Giordano, Cilèa. Dal 1890 al 1984: quasi un secolo di spettacoli storici Pietro Mascagni e la sua musica possono nel nome di Mascagni essere considerati a buon diritto i più au- Il 14 agosto 1890, infiammato dalla calura tentici protagonisti della gloriosa storia della riviera labronica, Cavalleria approda operistica del Teatro Goldoni di Livorno. nel maggiore teatro della città di Livorno, Il primo importante capitolo è la première appena tre mesi dopo il trionfo arriso nel- per Livorno dell’opera ‘prima’ del giovane la prestigiosa sede del Teatro Costanzi di astro nascente livornese, destinata a dare Roma all’atto unico vincitore del Concor- una svolta decisiva