1 Legal Critique

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animal Experimentation in India

Animal Defenders International ● National Anti-Vivisection Society Animal Experimentation in India Unfettered science: How lack of accountability and control has led to animal abuse and poor science “The greatness of a nation and its moral progress can be judged by the way its animals are treated. Vivisection is the blackest of all the black crimes that man is at present committing against God and His fair creation. It ill becomes us to invoke in our daily prayers the blessings of God, the Compassionate, if we in turn will not practise elementary compassion towards our fellow creatures.” And, “I abhor vivisection with my whole soul. All the scientific discoveries stained with the innocent blood I count as of no consequence.” Mahatma Gandhi Thanks With thanks to Maneka Gandhi and the Committee for the Purpose of Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals (CPCSEA) of India for their report on the use of animals in laboratories, which has been used for this critique of the state of scientific and medical research in India. Animal Defenders International and the National Anti-Vivisection Society UK fully support and encourage the efforts of the members of India’s CPCSEA to enforce standards and controls over the use of animals in laboratories in India, and their recommendation that facilities and practices in India’s research laboratories be brought up to international standards of good laboratory practice, good animal welfare, and good science. Contributors Jan Creamer Tim Phillips Chris Brock Robert Martin ©2003 Animal Defenders International & National Anti-Vivisection Society ISBN: Animal Defenders International 261 Goldhawk Road, London W12 9PE, UK tel. -

Laboratory Animals and the Art of Empathy D Thomas

197 RESEARCH ETHICS J Med Ethics: first published as 10.1136/jme.2003.006387 on 30 March 2005. Downloaded from Laboratory animals and the art of empathy D Thomas ............................................................................................................................... J Med Ethics 2005;31:197–204. doi: 10.1136/jme.2003.006387 Consistency is the hallmark of a coherent ethical take a big leap of imagination to empathise with the victims of animal experiments as well. In philosophy. When considering the morality of particular short: if we would not want done to ourselves behaviour, one should look to identify comparable what we do to laboratory animals, we should not situations and test one’s approach to the former against do it to them. one’s approach to the latter. The obvious comparator for Animals suffer animal experiments is non-consensual experiments on Crucially for the debate about the morality of people. In both cases, suffering and perhaps death is animal experiments, non-human animals suffer knowingly caused to the victim, the intended beneficiary is just as human ones do. Descartes may have described animals as ‘‘these mechanical robots someone else, and the victim does not consent. Animals [who] could give such a realistic illusion of suffer just as people do. As we condemn non-consensual agony’’ (my emphasis) but no serious scientist experiments on people, we should, if we are to be today doubts that the manifestation of agony is real, not illusory. Indeed, the whole pro-vivisec- consistent, condemn non-consensual experiments on tion case is based on the premise that animals animals. The alleged differences between the two practices are sufficiently similar to us physiologically, and often put forward do not stand up to scrutiny. -

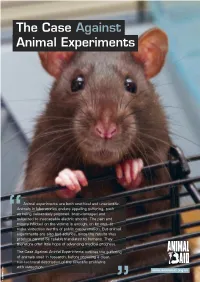

The Case Against Animal Experiments

The Case Against Animal Experiments Animal experiments are both unethical and unscientific. Animals in laboratories endure appalling suffering, such as being deliberately poisoned, brain-damaged and subjected to inescapable electric shocks. The pain and misery inflicted on the victims is enough, on its own, to make vivisection worthy of public condemnation. But animal “ “ experiments are also bad science, since the results they produce cannot be reliably translated to humans. They therefore offer little hope of advancing medical progress. The Case Against Animal Experiments outlines the suffering of animals used in research, before providing a clear, non-technical description of the scientific problems S E with vivisection. L I www.animalaid.org.uk C I N I M O D © How animals are used Contents Each year around four million How animals are used .......................... 1 animals are experimented on inside British laboratories. The suffering of animals in Dogs, cats, horses, monkeys, laboratories ........................................ 2 rats, rabbits and other animals Cruel experiments .................................... 2 are used, as well as hundreds A failing inspection regime ........................ 3 of thousands of genetically Secrecy and misinformation ...................... 4 modified mice. The most The GM mouse myth ................................ 4 common types of experiment The scientific case against either attempt to test how animal experiments .............................. 5 safe a substance is (toxicity Summary ............................................... -

Speciesism: a Form of Bigotry Or a Justified View? Evelyn Pluhar

-------~------------ - SPECIESISM: A FORM OF BIGOTRY OR A JUSTIFIED VIEW? EVELYN PLUHAR Pennsylvania State UniversityUniversity Fayette Campuscampus Editor's Note: An abridgedabridged version of this paper and thethe commentary on it by Prof.Prof. Sapontzis were delivered atat the December, 1987, meetingmeeting of the Society for the StudyStudy of Ethics and Animals held inin New York City.City. g~;~~~:Fr:iiil~~JmoDs. He ..... York: Dover, 1979 We humans tend to view ourselves as the paradigms of morally considerable beings. Humans, it is often claimed, are the most morally valuable (perhaps the ~ morally PHILOSOPHY valuable) beings on this planet. It is commonly assumed that "lesser" beings 83 BRIWEENBEIWEEN THE SPECIES should be sacrificed for our benefit. When For those who continue to think that it is not pressed to provide a rational defense for the wrong to eat and vivisect non humans, but belief in human pre-eminence, philosophers indefensible to do so to even less well have argued that our autonomous, richly mentally endowed humans, the issue should complex lives warrant our special status. be very pressing indeed. They stand accused Few, however, have argued that humans who of moral inconsistency by two very are incapable of autonomy may properly be different groups. Those who have become sacrificed to further the interests of normal convinced that moral considerability is not humans. restricted to humanity are urging that we cease even the painless exploitation of It was inevitable that this prima facie non humans. According to quite another, inconsistency would be challenged. Writers very disturbing view, we should consider like Peter Singer and Tom Regan advanced exploiting mentally defective humans in the argument from marginal cases to show addition to nonhumans. -

Action to End Animal Toxicity Testing

TH E WA Y FO R W A R D ACTION TO END ANIMAL TOXICITY TESTING REPORT COMPILED FOR THE BUAV BY The British Union for the European Coalition to DR GILL LANGLEY MA, PhD (CANTAB), MIBiol, CBiol Abolition of Vivisection End Animal Experiments Fo r e w o r d INTRODUCING THE EUROPEAN COALITION AND THE BUAV ACTION TO END ANIMAL TOXICITY TESTING The European Coalition to End Animal Experiments, (hereafter ‘the European Animal based toxicity tests cause massive suffering and are of dubious scientific Coalition’), is Europe’s leading alliance of animal protection organisations who have value; their credibility is based on established use rather than reliability or predictive come together to campaign for effective and long-lasting change for laboratory value.i animals. Formed in 1990 by animal groups across Europe, the Coalition now represents members across member states of the European Union plus a range of Testing programmes (such as the one proposed in the European Commission’s White international observer groups drawing together organisations with a range of Paper on a Future Chemicals Policy) could drastically increase the number of animals legislative, scientific and political expertise. Its membership base is currently used in toxicity experiments, or – with sufficient political will – can be used as an expanding to include those member groups in EU accession countries. Current opportunity to bring non-animal tests into use. Observer/Member groups of the European Coalition are as follows: This report demonstrates that animal tests can be replaced with modern, humane Members: ADDA (Spain); Animal Rights Sweden; Animalia (Finland); BUAV (UK); alternatives. -

Campaigns and Communications Assistant

Campaigns and Communications Assistant Job description and person specification Cruelty Free International is the leading organisation working to create a world where nobody wants or believes we need to experiment on animals. Our dedicated team are experts in their fields, combining award-winning campaigning, political lobbying, pioneering undercover investigations, scientific and legal expertise and corporate responsibility. Educating, challenging and inspiring others across the globe to respect and protect animals, we investigate and expose the reality of life for animals in laboratories, challenge decision-makers to make a positive difference for animals, and champion better science and cruelty free living. We are widely respected as an authority on animal testing issues and are frequently called on by governments, the media, corporations and official bodies for advice or expert opinion. We work professionally, building relationships with politicians, business leaders and officials, analysing legislation and challenging decision-making panels around the globe to act as the voice for animals in laboratories. With a history spanning over 100 years, Cruelty Free International has achieved so much for animals. Bringing the issue to public attention with our dynamic and determined approach, we have inspired generations of politicians, decision-makers and compassionate people to make a difference for animals used in experiments. As the problem has grown, we have stepped up to meet the challenge across the world, placing the issue on the global agenda for the first time. We have saved many thousands of animals from a life of suffering in laboratories, and together we can do so much more. Established in 1898, Cruelty Free International is firmly rooted in the early social justice movement. -

Creating a Better World for Rabbits

WINTER 2007 A P U B L I C AT I O N O F T H E A M E R I C A N A N T I -V I V I S E C T I O N SOCIETY Spring Ahead: Creating a Better World for Rabbits VOLUME CXV, NUMBER 1 ISSN 0274-7774 Contents FEATURES Managing Editor 2 A DAmAgeD RAbbit is still A RAbbit: 15 is the Domestic RAbbit the Right Crystal Schaeffer AnD otheR ReAsons why AnimAls compAnion foR you? Copy Editor shoulDn’t be pAtenteD By Caroline Gilbert, Founder/Director, Julie Cooper-Fratrik Rabbit Sanctuary, Inc. By Nina Mak, MS, AAVS Research Analyst Rabbits can be wonderful members of the family. AAVS launched the second phase of its Ban Are they the right companions for you? Animal Patents campaign in March. Our aim now is to stop a patent on rabbits who are subjected to STAFF painful eye experiments in order to develop eye 16 whAt RAbbits Can teAch us About Tracie Letterman, Esq., drop solutions. characteR-builDing Executive Director By Laura Ducceschi, MA, Jeanne Borden, Director of Animalearn Administration Assistant 6 blinDeD foR beAuty: Humane education can be used to help instill RAbbits useD in ProDuct testing Chris Derer, Membership Coordinator reverence and respect for animal life. Laura Ducceschi, Education Director By Vicki Katrinak, AAVS Policy Analyst Heather Gaghan, Director of Rabbits are the most recognized symbol associated Development & Member Services with compassionate shopping. This recognition is 17 DiD you Know? RAbbit Facts Nicole Green, Assistant Director of somewhat dubious, however, since rabbits are so Rabbits are fascinating animals. -

Moral Standing, the Value of Lives, and Speciesism

Moral StaDdlDg~ The Va,loe i I~ ~ -~ . ·ft: '_""l"~;'~~~" ~ :.Dl·i: ",_. ,8· .' "...... ll.S',liS·.>,<, - ,', ., -:iv',e'" a S'P::•• .<",' R.G. Frey Bowling Green State University The question of who or what has moral standing, of who or what is a member of the moral community, Editors~Note: has received wide exposure in recent years. Various answers have been extensively canvassed; and This essay by Professor Frey though controversy still envelops claims for the and the comments following it inclusion of the inanimate environment within the by Peter Singer were presented moral community, such claims on behalf of animals at the'Pacific Division Meeting (or, at least, the "higher" animals) are now widely of the Society for the Study of accepted. Morally, then, animals count. I do not Ethics and Animals, held in San myself think that we have needed a great deal of Francisco in March of 1987. argument to establish this point; but numerous writers, obviously, have thought otherwise. In any event, no work of mine has ever denied that animals count. In order to suffer, animals do not have to be self-conscious, to have interests or beliefs or language, to have desires and desires related to their own future, to exercise self-critical control of their behaviour, or to possess rights; and I, a utilitarian, take their sufferings into account, morally. Thus, the scope of the moral community, at least so far as but I have no quarrel with the general claim that ("higher") animals are concerned, is not something I they possess such standing. -

Red Cactus: the Life of Anna Kingsford

RED CACTUS: THE LIFE OF ANNA KINGSFORD Alan Pert Books & Writers Copyright © Alan Pert. All rights reserved. This book is copyright. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, (for example a fair dealing for the purposes of study, research, criticism or review) no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission. National Library of Australia CIP: Pert, Alan. Red cactus : the life of Anna Kingsford. Bibliography. Includes index. ISBN 9781740184052. 1. Kingsford, Anna Bonus, 1846-1888. 2. Theosophists - Great Britain - Biography. 3. Women physicians - Great Britain - Biography. I. Title. 299.934092 First published in Australia in 2006 Reprinted 2007 Books & Writers Network Pty Ltd P.O. Box W76, Watsons Bay NSW 2030 www.wildandwoolley.com.au Book design: Pat Woolley Set in Fournier In loving memory of my parents Ruby Adele Pert (1917-2004) Ronald Ernest Pert (1916-1994) Contents Chronology of the Life of Anna Kingsford - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -vii Introduction - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -1 1 Early Years - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -5 2 A Young Woman - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -17 3 Marriage - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -23 4 Anna’s Own Paper - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -35 5 Anna at Home - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Extrinsic and Intrinsic Arguments: Strategies for Promoting Animal Rights Katherine Perlo Ph.D.†

Extrinsic and Intrinsic Arguments: Strategies for Promoting Animal Rights Katherine Perlo Ph.D.† Introduction Animal rights campaigners disagree as to whether empirical arguments, based on facts such as those concerning nutrition, or ethical arguments, based on values such as the wrongness of hurting sentient beings, have greater validity and potential effectiveness. I want to address the issue in terms of “extrinsic” and “intrinsic” arguments – a distinction that corresponds only partly to the empirical and ethical couplet – and to make the case that animal rights campaigns are most effectively advanced through intrinsic appeals. “Extrinsic arguments” are those that seek to promote an aim and its underlying principle by appealing to considerations politically, historically, or logically separable from that aim and that principle. “Intrinsic arguments” appeal to considerations within and inseparable from the aim and principle. In this case, the aim is animal liberation and the principle is the moral equality of species. For example, the claim that vegetarianism (ideally, veganism) helps reduce animal suffering is an intrinsic argument, but it can also be justified on extrinsic grounds through appeal to its environmental benefits. You can separate vegetarianism from the benefit to the environment, since it is logically possible that the one might not lead to the other, and environmentalism is an independent political cause. But you cannot separate vegetarianism from the benefit to animals, since the word vegetarianism, whatever its etymology, is used to mean abstention from meat or from all animal products. You might say that “benefit to animals” is an independent issue in that there are other means of ameliorating animal suffering besides vegetarianism, or you might promote vegetarianism only for human health benefits. -

![Beyond Anthropocentrism: Critical Animal Studies and the Political Economy of Communication [1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7152/beyond-anthropocentrism-critical-animal-studies-and-the-political-economy-of-communication-1-2537152.webp)

Beyond Anthropocentrism: Critical Animal Studies and the Political Economy of Communication [1]

The Political Economy of Communication 4(2), 54–72 © The Author 2016 http://www.polecom.org Beyond Anthropocentrism: Critical Animal Studies and the Political Economy of Communication [1] Nuria Almiron, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona Keywords: anthropocentrism, speciesism, political economy of communication, ethics Abstract This article argues that the political economy of communication is ready and ethically obliged to expand its moral vision beyond human life, as other disciplines of the social sciences and humanities have already done. Such an expanded moral vision does not mean pushing human suffering to the background, but rather realizing that humans only form part of the planet, and are not above it. Not assigning individuals of other species the same moral consideration we do human beings has no ethical grounding and is actually deeply entangled with our own suffering within capitalist societies – it being particularly connected with human inequality, power relations, and economic interests. Decentering humanity to embrace a truly egalitarian view is the next natural step in a field driven by moral values and concerned with the inequality triggered by power relations. To make this step forward, this article considers the tenets of critical animal studies (CAS), an emerging interdisciplinary field which embraces traditional critical political economy concerns, including hegemonic power and oppression, from a non- anthropocentric moral stance. Critical media and communication scholars are concerned with what prevents human equality and social justice from blossoming. More particularly, they examine the fundamental role media and communication play in preventing or promoting social change. Those scholars devoted to the political economy of communication (PEC) focus upon the structural power relations involved in capitalism or, in Vincent Mosco’s words, in the “power relations that mutually constitute the production, distribution and consumption of resources, including communication resources” (2009: 2). -

“The Speciesism Gaze!?” an Ethical Discursive Analysis of Animal Right Posters from a Postcolonial, Eco- Critical and New Materialist Feminist Perspective

“The Speciesism Gaze!?” An ethical discursive analysis of animal right posters from a postcolonial, eco- critical and new materialist feminist perspective. ”Blicken av speciesism!?” En etisk diskursiv analys av djur rätts posters, utifrån postkolonial, eko-kritisk och new materialist feministiska perspektiv. Lena Johansson Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Gender Studies III Basic level, 15hp Supervisor: Wibke Straube Examiner: Ulf Mellström Date: June 7, 2017 Serial number Abstract Our western society and lifestyle is to a considerable extent depended on the way we perceive and treat our co-existing non-human species. Industrial farming, vivisection, sports, circuses etcetera are just a few examples of how human use and exploit animal bodies for own gain. A phenomenon that in many ways, is perceived, as natural and normal, and therefore seldom discussed. The thesis purpose is to problematize this phenomenon by examine, what I call “The Speciesism Gaze”, through analysis of posters that promote animal rights, selected online, through the search domain Google. The theoretical framework used, are theories focusing on intersectionality, derived within postcolonial-, eco-critical and new materialist feminism. A brief introduction of animal right movements, its linking to feminism activism and theories derived within affect theory is presented as background for the analysis. As method, I use critical discourse analysis, focusing on intertextuality of the posters context. Asking what discourses emerge, challenging the anthropocentric and androcentric western dualistic hierarchy, whilst displaying mutually reinforced structures of sexism, racism and speciesism? I discuss the western historical and cultural human idea that the human species is separated from nature and animal, and where the “right” human subject standard is perceived as male, white, heterosexual and western in the Anthropocene age.