All Closest Neighbors Are Proper Delaunay Edges Generalized, and Its Application to Parallel Algorithms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Computational Geometry • Lecture Delaunay Triangulation

Computational Geometry • Lecture Delaunay Triangulation INSTITUTE FOR THEORETICAL INFORMATICS · FACULTY OF INFORMATICS Tamara Mchedlidze · Darren Strash 7.12.2015 1 Tamara Mchedlidze · Darren Strash Delaunay-Triangulations Modelling a Terrain Sample points p = (xp; yp; zp) Projection π(p) = (px; py; 0) Interpolation 1: each point gets the height of the nearest sample point 3-4 Tamara Mchedlidze · Darren Strash Delaunay-Triangulations Modelling a Terrain Sample points p = (xp; yp; zp) Projection π(p) = (px; py; 0) Interpolation 2: triangulate the set of sample points and interpolate on the triangles 3-7 Tamara Mchedlidze · Darren Strash Delaunay-Triangulations Triangulation of a Point Set Def.: A triangulation of a point set P ⊂ R2 is a maximal planar subdivision with a vertex set P . CH(P ) Obs.: all internal faces are triangles outer face is the complement of the convex hull Theorem 1: Let P be a set of n points, not all collinear. Let h be the number of points in CH(P ). Then any triangulation of P has (2n − 2 − h) triangles and (3n − 3 − h) edges. 4 Tamara Mchedlidze · Darren Strash Delaunay-Triangulations Back to Height Interpolation 1240 1240 0 19 0 19 0 0 1000 20 1000 20 980 980 10 36 10 36 990 990 6 6 1008 28 1008 28 4 23 4 23 890 890 Height 985 Height 23 Intuition: Avoid narrow triangles! Or: maximize the smallest angle! 5 Tamara Mchedlidze · Darren Strash Delaunay-Triangulations Angle-optimal Triangulations Def.: Let P ⊂ R2 be a set of points, T be a triangulation of P and m be the number of the triangles. -

Constrained a Fast Algorithm for Generating Delaunay

004s7949/93 56.00 + 0.00 if) 1993 Pcrgamon Press Ltd A FAST ALGORITHM FOR GENERATING CONSTRAINED DELAUNAY TRIANGULATIONS S. W. SLOAN Department of Civil Engineering and Surveying, University of Newcastle, Shortland, NSW 2308, Australia {Received 4 March 1992) Abstract-A fast algorithm for generating constrained two-dimensional Delaunay triangulations is described. The scheme permits certain edges to be specified in the final t~an~ation, such as those that correspond to domain boundaries or natural interfaces, and is suitable for mesh generation and contour plotting applications. Detailed timing statistics indicate that its CPU time requhement is roughly proportional to the number of points in the data set. Subject to the conditions imposed by the edge constraints, the Delaunay scheme automatically avoids the formation of long thin triangles and thus gives high quality grids. A major advantage of the method is that it does not require extra points to be added to the data set in order to ensure that the specified edges are present. I~RODU~ON to be degenerate since two valid Delaunay triangu- lations are possible. Although it leads to a loss of Triangulation schemes are used in a variety of uniqueness, degeneracy is seldom a cause for concern scientific applications including contour plotting, since a triangulation may always be generated by volume estimation, and mesh generation for finite making an arbitrary, but consistent, choice between element analysis. Some of the most successful tech- two alternative patterns. niques are undoubtedly those that are based on the One major advantage of the Delaunay triangu- Delaunay triangulation. lation, as opposed to a triangulation constructed To describe the construction of a Delaunay triangu- heu~stically, is that it automati~ily avoids the lation, and hence explain some of its properties, it is creation of long thin triangles, with small included convenient to consider the corresponding Voronoi angles, wherever this is possible. -

Planar Delaunay Triangulations and Proximity Structures

Wolfgang Mulzer Institut für Informatik Planar Delaunay Triangulations and Proximity Structures Proximity Structures Given: a set P of n points in the plane proximity structure: a structure that “encodes useful information about the local relationships of the points in P” Planar Delaunay Triangulations and Proximity Structures 2 Proximity Structures Given: a set P of n points in the plane proximity structure: a structure that “encodes useful information about the local relationships of the points in P” Planar Delaunay Triangulations and Proximity Structures 3 Proximity Structures Given: a set P of n points in the plane proximity structure: a structure that “encodes useful information about the local relationships of the points in P” Planar Delaunay Triangulations and Proximity Structures 4 Proximity Structures Reduction from sorting → Ω usually need (n log n) to build a proximity structure Planar Delaunay Triangulations and Proximity Structures 5 Proximity Structures But: shouldn’t one proximity structure suffice to construct another proximity structure faster? Voronoi diagram → Quadtree s s s s s Planar Delaunay Triangulations and Proximity Structures 6 Proximity Structures Point sets may exhibit strange behaviors, so this is not always easy. Planar Delaunay Triangulations and Proximity Structures 7 Proximity Structures There might be clusters… Planar Delaunay Triangulations and Proximity Structures 8 Proximity Structures …high degrees… Planar Delaunay Triangulations and Proximity Structures 9 Proximity Structures or large spread. Planar -

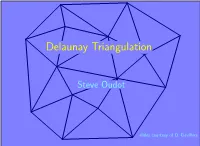

Delaunay Triangulation

Delaunay Triangulation Steve Oudot slides courtesy of O. Devillers Outline 1. Definition and Examples 2. Applications 3. Basic properties 4. Construction Definition Classical example looking for nearest neighbor Classical example looking for nearest neighbor Classical example looking for nearest neighbor Classical example looking for nearest neighbor Voronoi Classical example Georgy F. Voronoi (1868–1908) Vi = {q; ∀j =6 i|qpi| ≤ |qpj|} Voronoi Classical example Delaunay Boris N. Delaunay (1890–1980) Voronoi Classical example Delaunay Boris N. Delaunay (1890–1980) Voronoi ↔ geometry Delaunay ↔ topology Voronoi faces of the Voronoi diagram Voronoi faces of the Voronoi diagram Voronoi faces of the Voronoi diagram Voronoi faces of the Voronoi diagram Voronoi is everywhere THE Delaunay property Voronoi Voronoi Empty sphere Voronoi Delaunay Empty sphere Voronoi Delaunay Empty sphere Several applications nearest neighbor graph nearest neighbor graph p q q nearest neighbor of p ⇒ pq Delaunay edge nearest neighbor graph k nearest neighbors kth nearest neighbor k − 1 nearest neighbors query point k nearest neighbors kth nearest neighbor k − 1 nearest neighbors query point k nearest neighbors kth nearest neighbor k − 1 nearest neighbors query point Largest empty circle Largest empty circle MST MST Other applications Reconstruction Other applications Reconstruction Meshing Other applications Reconstruction Meshing / Remeshing Other applications Reconstruction Meshing / Remeshing Other applications Reconstruction Meshing / Remeshing Path planning Other -

Two Algorithms for Constructing a Delaunay Triangulation 1

International Journal of Computer and Information Sciences, Vol. 9, No. 3, 1980 Two Algorithms for Constructing a Delaunay Triangulation 1 D. T. Lee 2 and B. J. Schachter 3 Received July 1978; revised February 1980 This paper provides a unified discussion of the Delaunay triangulation. Its geometric properties are reviewed and several applications are discussed. Two algorithms are presented for constructing the triangulation over a planar set of Npoints. The first algorithm uses a divide-and-conquer approach. It runs in O(Nlog N) time, which is asymptotically optimal. The second algorithm is iterative and requires O(N 2) time in the worst case. However, its average case performance is comparable to that of the first algorithm. KEY WORDS: Delaunay triangulation; triangulation; divide-and-con- quer; Voronoi tessellation; computational geometry; analysis of algorithms. 1. INTRODUCTION In this paper we consider the problem of triangulating a set of points in the plane. Let V be a set of N ~> 3 distinct points in the Euclidean plane. We assume that these points are not all colinear. Let E be the set of (n) straight- line segments (edges) between vertices in V. Two edges el, e~ ~ E, el ~ e~, will be said to properly intersect if they intersect at a point other than their endpoints. A triangulation of V is a planar straight-line graph G(V, E') for which E' is a maximal subset of E such that no two edges of E' properly intersect.~16~ 1 This work was supported in part by the National Science Foundation under grant MCS-76-17321 and the Joint Services Electronics Program under contract DAAB-07- 72-0259. -

Background on Meshes

Background on Meshes Pierre Alliez Inria Sophia Antipolis - Mediterranee Definitions . Mesh: Cellular complex partitioning an input domain into elementary cells. Elementary cell: Admits a bounded description. Cellular complex: Two cells are disjoint or share a lower dimensional face. Variety . Domains: 2D, 3D, nD, surfaces, manifolds, periodic vs non-periodic, etc. Variety . Elements: simplices (triangles, tetrahedra), quadrangles, polygons, hexahedra, arbitrary cells. … Variety . Structured mesh: All interior nodes have an equal number of adjacent elements. Unstructured mesh: Any number of elements can meet at a single vertex. Variety . Anisotropic vs Isotropic Variety . Element distribution: Uniform vs adapted Variety . Grading: Smooth vs fast Required Properties . control/optimization over: . #elements . shape . orientation . size . grading . Boundary approximation error . … (application dependent) Mesh Generation . Input: . Domain boundary + internal constraints . Constraints . Sizing . Grading . Shape . Topology . … Voronoi Diagram and Delaunay triangulation Voronoi Diagram Voronoi Diagram . The collection of the non-empty Voronoi regions and their faces, together with their incidence relations, constitute a cell complex called the Voronoi diagram of E. The locus of points which are equidistant to two sites pi and pj is called a bisector, all bisectors being affine subspaces of IRd (lines in 2D). demo Voronoi Diagram . A Voronoi cell of a site pi defined as the intersection of closed half-spaces bounded by bisectors. Implies: All Voronoi cells are convex. demo Voronoi Diagram . Voronoi cells may be unbounded with unbounded bisectors. Happens when a site pi is on the boundary of the convex hull of E. demo Voronoi Diagram . Voronoi cells have faces of different dimensions. In 2D, a face of dimension k is the intersection of 3 - k Voronoi cells. -

Delaunay Triangulations in the Plane

DELAUNAY TRIANGULATIONS IN THE PLANE HANG SI Contents Introduction 1 1. Definitions and properties 1 1.1. Voronoi diagrams 2 1.2. The empty circumcircle property 4 1.3. The lifting transformation 7 2. Lawson's flip algorithm 10 2.1. The Delaunay lemma 10 2.2. Edge flips and Lawson's algorithm 12 2.3. Optimal properties of Delaunay triangulations 15 2.4. The (undirected) flip graph 17 3. Randomized incremental flip algorithm 18 3.1. Inserting a vertex 18 3.2. Description of the algorithm 18 3.3. Worst-case running time 19 3.4. The expected number of flips 20 3.5. Point location 21 Exercises 23 References 25 Introduction This chapter introduces the most fundamental geometric structures { Delaunay tri- angulation as well as its dual Voronoi diagram. We will start with their definitions and properties. Then we introduce simple and efficient algorithms to construct them in the plane. We first learn a useful and straightforward algorithm { Lawson's edge flip algo- rithm { which transforms any triangulation into the Delaunay triangulation. We will prove its termination and correctness. From this algorithm, we will show many optimal properties of Delaunay triangulations. We then introduce a randomized incremental flip algorithm to construct Delaunay triangulations and prove its expected runtime is optimal. 1. Definitions and properties This section introduces the Delaunay triangulation of a finite point set in the plane. It is introduced by the Russian mathematician Boris Nikolaevich Delone (1890{1980) 1 2 HANG SI in 1934 [4]. It is a triangulation with many optimal properties. There are many ways to define Delaunay triangulation, which also shows different properties of it. -

Delaunay Triangulation of Manifolds Jean-Daniel Boissonnat, Ramsay Dyer, Arijit Ghosh

Delaunay Triangulation of Manifolds Jean-Daniel Boissonnat, Ramsay Dyer, Arijit Ghosh To cite this version: Jean-Daniel Boissonnat, Ramsay Dyer, Arijit Ghosh. Delaunay Triangulation of Manifolds. Founda- tions of Computational Mathematics, Springer Verlag, 2017, 45, pp.38. 10.1007/s10208-017-9344-1. hal-01509888 HAL Id: hal-01509888 https://hal.inria.fr/hal-01509888 Submitted on 18 Apr 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Delaunay triangulation of manifolds Jean-Daniel Boissonnat ∗ Ramsay Dyer y Arijit Ghosh z April 18, 2017 Abstract We present an algorithm for producing Delaunay triangulations of manifolds. The algorithm can accommodate abstract manifolds that are not presented as submanifolds of Euclidean space. Given a set of sample points and an atlas on a compact manifold, a manifold Delaunay complex is produced for a perturbed point set provided the transition functions are bi-Lipschitz with a constant close to 1, and the original sample points meet a local density requirement; no smoothness assumptions are required. If the transition functions are smooth, the output is a triangulation of the manifold. The output complex is naturally endowed with a piecewise flat metric which, when the original manifold is Riemannian, is a close approximation of the original Riemannian metric. -

27 VORONOI DIAGRAMS and DELAUNAY TRIANGULATIONS Steven Fortune

27 VORONOI DIAGRAMS AND DELAUNAY TRIANGULATIONS Steven Fortune INTRODUCTION The Voronoi diagram of a set of sites partitions space into regions, one per site; the region for a site s consists of all points closer to s than to any other site. The dual of the Voronoi diagram, the Delaunay triangulation, is the unique triangulation such that the circumsphere of every simplex contains no sites in its interior. Voronoi dia- grams and Delaunay triangulations have been rediscovered or applied in many areas of mathematics and the natural sciences; they are central topics in computational geometry, with hundreds of papers discussing algorithms and extensions. Section 27.1 discusses the definition and basic properties in the usual case of point sites in Rd with the Euclidean metric, while Section 27.2 gives basic algo- rithms. Some of the many extensions obtained by varying metric, sites, environ- ment, and constraints are discussed in Section 27.3. Section 27.4 finishes with some interesting and nonobvious structural properties of Voronoi diagrams and Delaunay triangulations. GLOSSARY Site: A defining object for a Voronoi diagram or Delaunay triangulation. Also generator, source, Voronoi point. Voronoi face: The set of points for which a single site is closest (or more generally a set of sites is closest). Also Voronoi region, Voronoi cell. Voronoi diagram: The set of all Voronoi faces. Also Thiessen diagram, Wigner- Seitz diagram, Blum transform, Dirichlet tessellation. Delaunay triangulation: The unique triangulation of a set of sites such that the circumsphere of each full-dimensional simplex has no sites in its interior. 27.1 POINT SITES IN THE EUCLIDEAN METRIC See [Aur91, Ede87, For95] for more details and proofs of material in this section. -

Algorithmica (1999) 24: 243–269 Algorithmica © 1999 Springer-Verlag New York Inc

Algorithmica (1999) 24: 243–269 Algorithmica © 1999 Springer-Verlag New York Inc. Design and Implementation of a Practical Parallel Delaunay Algorithm1 G. E. Blelloch,2 J. C. Hardwick,3 G. L. Miller,2 and D. Talmor4 Abstract. This paper describes the design and implementation of a practical parallel algorithm for Delau- nay triangulation that works well on general distributions. Although there have been many theoretical parallel algorithms for the problem, and some implementations based on bucketing that work well for uniform distribu- tions, there has been little work on implementations for general distributions. We use the well known reduction of 2D Delaunay triangulation to find the 3D convex hull of points on a paraboloid. Based on this reduction we developed a variant of the Edelsbrunner and Shi 3D convex hull algorithm, specialized for the case when the point set lies on a paraboloid. This simplification reduces the work required by the algorithm (number of operations) from O(n log2 n) to O(n log n). The depth (parallel time) is O(log3 n) on a CREW PRAM. The algorithm is simpler than previous O(n log n) work parallel algorithms leading to smaller constants. Initial experiments using a variety of distributions showed that our parallel algorithm was within a factor of 2 in work from the best sequential algorithm. Based on these promising results, the algorithm was implemented using C and an MPI-based toolkit. Compared with previous work, the resulting implementation achieves significantly better speedups over good sequential code, does not assume a uniform distribution of points, and is widely portable due to its use of MPI as a communication mechanism. -

On Crossing Numbers of Geometric Proximity Graphs

On Crossing Numbers of Geometric Proximity Graphs Bernardo M. Abrego¶ ¤ Ruy Fabila-Monroyy Silvia Fern¶andez-Merchant¤ David Flores-Pe~nalozaz Ferran Hurtadox Vera Sacrist¶anx Maria Saumellx Abstract Let P be a set of n points in the plane. A geometric proximity graph on P is a graph where two points are connected by a straight-line segment if they satisfy some prescribed proximity rule. We consider four classes of higher order proximity graphs, namely, the k-nearest neighbor graph, the k-relative neighborhood graph, the k-Gabriel graph and the k-Delaunay graph. For k = 0 (k = 1 in the case of the k-nearest neighbor graph) these graphs are plane, but for higher values of k in general they contain crossings. In this paper we provide lower and upper bounds on their minimum and maximum number of crossings. We give general bounds and we also study particular cases that are especially interesting from the viewpoint of applications. These cases include the 1-Delaunay graph and the k-nearest neighbor graph for small values of k: Keywords Proximity graphs; geometric graphs; crossing number. 1 Introduction and basic notation A geometric graph on a point set P is a pair G = (P; E) in which the vertex set P is assumed to be in general position, i.e., no three points are collinear, and the set E of edges consists of straight-line segments with endpoints in P . Notice that the focus is more on the drawing rather than on the underlying graph, as carefully pointed out by Brass, Moser and Pach in their survey book ([6], page 373). -

Simple and Fast Nearest Neighbor Search

Birn et al.: Nearest Neighbors 1 Simple and Fast Nearest Neighbor Search Marcel Birn, Manuel Holtgrewe, Peter Sanders, Johannes Singler Birn et al.: Nearest Neighbors 2 2D Nearest Neighbor Search Preprocess S = {(x1,y1),..., (xn,yn)}. Query: q = (x,y) −→ closest point in S (Euclidean distance) Birn et al.: Nearest Neighbors 3 Application Example Geographic Information Systems, e.g., Route Planning Birn et al.: Nearest Neighbors 4 A Greedy Algorithm Preprocessing: Delaunay Triangulation (not Yao graph etc. !) Query: Start at any point in S. Follow any edge towards q. Iterate until no improvement possible. still linear time. Birn et al.: Nearest Neighbors 5 Multiple Levels Start with a sample of points from S. Closest point in sample → starting point in next level. How many levels? Complicated data structure? Birn et al.: Nearest Neighbors 6 n Levels? Randomly number points in S. Function nlevelNN(q) u:= s1 538 1 6 4 2 7 for i := 1 to n do u:= greedyNN(u, q, DT(s1..k)) return u Sounds like quadratic space and at least linear time??? Birn et al.: Nearest Neighbors 7 Full Delaunay Hierarchy (FDH) n G:= (1..n, [ Ek) i=1 where Gk =(1..k,Ek):= Delaunay triangulation of points 1..k. 538 1 6 4 2 7 538 1 6 4 2 7 G has a linear expected number of edges e.g., [Guibas et al. 92]. Birn et al.: Nearest Neighbors 8 FDH-Based n Level Search! Procedure nn(q, {s1,...,sn}) u:= s1 repeat foreach neighbor v of u in G with u > v in increasing order do invariant u is nearest neighbor of q wrt 1..v − 1 if ||q − sv||2 < ||q − su||2 then 538 1 6 4 2 7 u:= v break for loop until no improvement found return u Birn et al.: Nearest Neighbors 9 Analysis Theorem: Expected number of nodes visited ≤ ln n + 1 Proof Idea: si is visited ⇔si is closest to q wrt 1..i.