Chapter 13—Purchasing an Ax

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Essential Block Plane How to Choose and Use Woodworking’S Most Popular Trimmer

The Essential Block Plane How to choose and use woodworking’s most popular trimmer By Craig Bentzley It’s no secret that I love hand plane. Available in a variety of What to look for planes and own way too many in a block plane of them–about 250 at last it’s small, relatively inexpensive, As shown in Figure 1 and count. Many of them perform andconfigurations even kind of (as cute. shown But above),it’s Photo A, a block plane is a highly specialized tasks and fairly basic tool. That said, for don’t see use very often. But up and tuned, a good quality good performance, avoid cheap, there’s one type of plane that’s blockdefinitely plane not is aadept toy. Properly at handling set rudimentary hardware store a stand-out exception: the block all sorts of shop chores and is versions. The most important plane. In fact, when I’m asked likely to become one of your most features to look for in a good by beginning woodworkers used hand tools. I’ll discuss what what plane they should to look for in a good block plane, reliable and easy-to-use depth-of- start out with, that’s the one how to set one up, and how to cutblock adjustment, plane include and a an flat adjustable sole, a that always tops the list. use it to your best advantage. throat. You’ll also want the tool The ubiquitous block plane Once you make friends with to feel comfortable in your hand. is probably owned by more a block plane, you’ll wonder Unlike most bench planes, the people than any other hand how you did without one. -

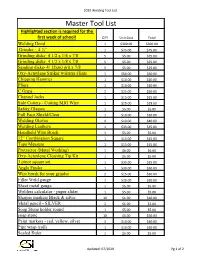

2020 Welding Tool List

2020 Welding Tool List Master Tool List Highlighted section is required for the first week of school! QTY Unit Cost Total Welding Hood 1 $300.00 $300.00 Grinder – 4 ½” 1 $75.00 $75.00 Grinding disks- 4 1/2 x 1/4 x 7/8 5 $5.00 $25.00 Grinding disks- 4 1/2 x 1/8 x 7/8 5 $5.00 $25.00 Sanding disks- 4/ 12x60 grit x 7/8 5 $5.00 $25.00 Oxy-Acteylene Striker w/Extra Flints 1 $50.00 $50.00 Chipping Hammer 1 $10.00 $10.00 Pliers 1 $10.00 $10.00 C Grips 2 $25.00 $50.00 Channel locks 1 $15.00 $15.00 Side Cutters - Cutting MIG Wire 1 $15.00 $15.00 Safety Glasses 1 $5.00 $5.00 Full Face Shield/Clear 1 $10.00 $10.00 Welding Gloves 4 $10.00 $40.00 Welding Leathers 1 $35.00 $35.00 Handheld Wire Brush 1 $5.00 $5.00 12” Combination Square 1 $15.00 $15.00 Tape Measure 1 $15.00 $15.00 Protractor (Metal Working) 1 $6.00 $6.00 Oxy-Acteylene Cleaning Tip Kit 1 $5.00 $5.00 3 piece square set 1 $35.00 $35.00 Angle Finder 1 $30.00 $30.00 Wire brush for your grinder 2 $15.00 $30.00 Fillet Weld gauge 1 $20.00 $20.00 Sheet metal gauge 1 $5.00 $5.00 Welders calculator - paper slider 1 $5.00 $5.00 Sharpie markers Black & silver 10 $1.00 $10.00 Metal pencil - SILVER 2 $1.00 $2.00 Soap Stone holder round 1 $5.00 $5.00 soap stone 10 $5.00 $50.00 Paint markers - red, yellow, silver 3 $10.00 $30.00 Pipe wrap (roll) 1 $10.00 $10.00 Scaled Ruler 1 $5.00 $5.00 Updated: 07/2020 Pg 1 of 2 2020 Welding Tool List Drafting pencil 1 $10.00 $10.00 Graphing Paper 1 $10.00 $10.00 Extra Large Compass (10"-15") 1 $20.00 $20.00 Scribe 1 $50.00 $50.00 Needle nose plyers/3 pc kit 1 $25.00 -

Power Brush Catalog.Pdf

POWER BRUSHES POWER BRUSHES CHOOSE QUALITY Superior construction, the highest quality materials, state of the art manufacturing, and exacting quality standards WHY WEILER deliver the most consistent brush performance. Each Weiler brush is designed to provide the best performance at the lowest cost-of-use. That's why we re-engineered our 4" stringer bead brush to deliver MAXimum impact, letting the wire do the work. Our beefed up Roughneck® Max brush delivers up to BONDED ABRASIVES twice the life. Combine that with the hardest, strongest wire and an improved knot design to MAXimize cleaning power and you have a brush that you can trust when your name is on the line. Technical Information .................................................... 48-56 Knot Wire Wheels ........................................................... 57-63 Weld Cleaning Brushes ................................................. 62-63 Crimped Wire Wheels .................................................... 64-71 COATED ABRASIVES Nylon & Tampico Wheels ...................................................72 Cup Brushes .................................................................... 73-75 Stem-Mounted End Brushes ......................................... 76-79 Crosshole Deburring Brushes ............................................80 Power & Hand Tube Brushes ....................................... 81-85 Crossflex Honing Brushes ............................................. 86-89 Miniature Brushes .......................................................... 90-91 Non-Sparking -

Finishing Sander

Finishing Sander I. Competencies Given a properly adjusted finishing sander, accessories, instruction and demonstration of use, each student will be able to: A. Identify the major parts of the finishing sander. B. Pass a written test on safety and operating procedures of the finishing sander with 100 percent accuracy. C. Demonstrate ability to use the finishing sander, following suggested safety rules and correct operation procedures. II. Instructional Materials and Procedures A. Identification of basic finishing sander parts. 1. Brush Holder 6. Paper Clamp 2. Switch Lock 7. Pad 3. Trigger Switch 8. Paper Clamp 4. Handle 9. Aluminum Housing 5. Cord Strain Reliever 10. Front Hand Knob B. Finishing Sander Safety 1. Wear safety glasses at all times when using the finishing sander. 2. Wear a dust mask or respirator to prevent breathing the fine saw dust particles that are generated by the finishing sander. 3. Keep the electrical and extension cords away from the work area. 4. Wear hearing protectors when using finishing sanders that are noisy. 5. Secure or clamp the stock before starting the sanding operation. 6. Watch out for slick walking suffices when using the finishing sander. Fine dust particles will settle on the floor making it slick. 7. Visually inspect the sander to make sure the electrical cord is not frayed or pulled out of the sander housing. If either condition exists repair the sander before using. 8. If the sander sparks excessively when being used check the brushes. Reseat or replace the brushes as necessary to reduce sparking. 9. Do not over-extend and get off balance when using the finishing sander. -

Technology at Rocky Flats, Contact David Maloney, Kaiser-Hill Company, (303) 966-7566, Or Gary Huffman, DOE, Rocky Flats Field Office, (303) 966-7490

Demonstration & Deployment Summary Ultra-high Pressure Water Jet Used to Remotely Cut B774 Tank Summary chanical cutting with Sawzalls or nibblers will break loose Liquids used for process- fixatives and cause re-suspension of contaminants. Workers ing plutonium at Rocky are also exposed to cutting hazards that have the potential to Flats required hundreds breach personal protective equipment (PPE). of tanks for storage and Thermal cutting using plasma-arc requires construction of treatment. Many of specialized containment and ventilation systems to protect these tanks are so large workers and control dust and fumes. Installation of these they had to be installed systems is engineering-intensive, time consuming and prior to the completion expensive. Thermal cutting also creates potential toxic and of the buildings that corrosive hazards when the tank contains organic or housed them. Some tanks halogenated organic residues. contain polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), oth- D&D managers envisioned alternative cutting methods that ers may contain beryl- would reduce work- lium, and nearly all of ers’ exposure to them are contaminated cutting hazards, er- with plutonium and am- gonomic challenges ericium. and the potential for airborne radioactiv- Large tanks, such as the 7,300- ity and beryllium gallon New Tank 40 in building contamination that 774, are far too large to be re- result from thermal moved from the building. To size- or mechanical size- reduce New Tank 40, workers reduction methods. would have used nibblers to com- plete three cuts around the tank’s 20-foot circumference. The ultra- The high pressure water-jet, manufac- Technology tured by Jet Edge, instead made Jet Edge of St. -

Water Jet Cutting a Technology on the Rise

Water Jet Cutting A Technology on the Rise Water Jet Cutting- A Technology on the Rise Foreword: Siberia to Iceland, from Norway to South The purpose of this brochure is to give the Africa. reader a rough overview of Waterjet Specially trained technicians are constantly Cutting. In addition to precise cutting of on duty and can help you immediately at various materials as presented, many any time. special applications i.e. medical and in the decommissioning and demolition field Service and wear parts are shipped within exist – these however being outside the 24 hours. scope of this text. For any additional Our contract-cutting department takes information, our KMT Waterjet team is care of our customers’ needs to the fullest, always available. Also, we would like to enabling us to perform test-cutting welcome you to visit our homepage procedures in order to optimize the www.kmt-waterjet.com, where you have cutting method, allowing you for the option of downloading useful files. economically and technically sound In order for you to get a better operation of your machines. understanding of KMT Waterjet Systems, The KMT Waterjet team in Bad Nauheim is we would also like to take this opportunity always available to answer your questions! to present our company. In the Autumn of 2003, KMT AB of Sweden purchased the Waterjet Cutting Division from Ingersoll-Rand. The KMT Corporation is an Internationally active corporation with over 700 employees worldwide. KMT Waterjet Systems employs 200 people. Further KMT brands include UVA, LIDKOPING, KMT Robotic Solutions, KMT Aqua-Dyne, KMT McCartney, and KMT H2O. -

The Original. Versatile and Powerful

iNTEriOr CONSTruCTiON The Original. Versatile and powerful. FEiN MultiMastEr – the universal system for interior construction and renovation NEW! Now available in a cordless version From the inventor of the power tool: FEIN MultiMaster. More than 40 year’s experience is built into this system. Original FEiN accessories – developed for the MultiMastEr. FEIN brought the first oscillating power tool to the market Original FEIN accessories guarantee outstanding results and an over 40 years ago. These decades of experience are built into unrivalled long service life. It handles all common renovation and the FEIN MultiMaster, making this universal system for interior interior construction work for professionals and also provides construction and renovation unique in its diversity of applications unique application solutions. Maximum performance, safety and and performance. In addition, the MultiMaster impresses with high reliability are guaranteed with the FEIN MultiMaster. quality components and is an indispensible companion for trade and industrial professionals. Technology / Quality The Original Page 4 The MultiMaster Page 6 The MultiMaster Cordless Page 7 Accessories know-how Page 10 2 FEiN MultiMastEr Cordless – mobile and powerful. Your benefits with FEiN oscillating power tools: The new battery version makes the FEIN MultiMaster more flexible and convenient than ever. Cordless, but with identical performance, ɰ More than 40 year’s experience with oscillation technology. so work can be done anywhere, even without a power supply. And ɰ The high “Made in Germany” quality you expect. all this in the durable quality that you expect from a real Original. ɰ Unrivalled performance and versatility. ɰ Original FEIN accessories for perfect results and maximum tool life. -

Cutting Tools Columbus Fleet Industrial Supply Canton Fleet Industrial Supply Canton First Aid & Safety

Cutting Tools Columbus Fleet Industrial Supply Canton Fleet Industrial Supply Canton First Aid & Safety www.cfisgroup.com Phone: 614-332-7464 1 Cutting Tools Full Sets Part # TYPE 330-040 29 PC Set Flip-Out (64th) 330-039 29 PC Set Orange Round 330-030 1-60 Set 330-032 A-Z Set 330-045 29 PC Reduced Shank 330-070 29 PC Cobalt Set Empty Drill Index Empty Index Part # TYPE 330-001 Drill Guage 330-002 15 PC Empty (32nd) 330-003 29 PC Empty (64th) 330-005 1-60 Empty 330-007 A-Z Empty www.cfisgroup.com Phone: 614-332-7464 2 Cutting Tools Drill Sets & Empty Index Full Sets Part # TYPE 330-048 S&D Drill Set 4-PC 330-050 S&D Drill Set 8-PC 9/16, 13/16, 5/8, 7/8, 11/16, 15/16, 3/4, 1” Empty Index Part # TYPE 330-015 S&D Drill Empty Drill Sets & Empty Index Full Sets Empty Index Part # TYPE Part # TYPE 330-042 56 Piece Drill Set 330-020 56 Piece Drill Empty 3 ea 1/16” – 1/4” 2 ea 17/64” – 3/8” 1 ea 11/16” – 1/2” Drill Sets & Empty Index Full Sets Part # TYPE 330-043 115 pc Drill Set www.cfisgroup.com Phone: 614-332-7464 3 Cutting Tools Accu-Lube Gold Cutting / Tapping UltraS-tCicukt Gold SLtuibcrikcants Part # QTY 252-000 Ea 2.2 oz Accu-Lube Gold Spray • High performance cutting tool lubricants in an easy to apply, easy to Part # QTY carry solid stick applicator or spray. -

Cutting & Welding Products

WELDING PLASMA OXYFUEL ACCESSORIES Cutting & Welding Products FirepowerOnline.com Advantage Firepower® Products Performance, Value and Ease of Use Firepower, a leader in metal cutting, gas control and specialty welding solutions, is meeting the needs of people who demand professional-quality results, through a refined portfolio of Firepower branded products. These products represent the leading edge in design, performance, quality and safety, backed by 100 years of proven innovation. The Firepower lineup offers superior performance, excellent value and ease-of-use that helps the craftsman to get the job done right the first time. Firepower OxyFuel, incorporating the authentic Victor® torch and regulator range, is the heart of the Firepower family, with system solutions and components designed for individual needs. The OxyFuel range will perform a wide spectrum of tasks, from brazing sheet metal to cutting up to six-inch thick steel. Firepower Plasma offers a broad range of Manual Plasma Cutters capable of slicing up to 1-1/2 inches in multiple metals. These machines are easy to use and can cut a variety of metals, including steel, aluminum, galvanized and more. Firepower MST, with its new line up, comprises the core of the Firepower Welding range. Its technology has changed the game, setting a new standard for portable welding equipment. The 3-in-1 power supplies provide MIG, Stick and TIG capabilities in one integrated system. Firepower Velocity™ consumables allow for easy tip changes (no tip threads, no tools) while delivering longer life. Our consumables are designed for total welding flexibility and optimized welding performance with each process. Firepower draws from the heritage and quality of Victor and Tweco equipment, with the added advantage of utilizing our excellence in product support, service and application know-how. -

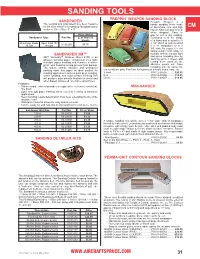

Sanding Tools

SANDING TOOLS PREPPIN’ WEAPON SANDING BLOCK SANDPAPER Preppin’ Weapon is a The weights and grits listed have been found to handy sanding block made be the most ef fec tive for sanding fiberglass/epoxy of Styrofoam core and high CM surfaces. Sheet Size: 9” x 11”. impact ABS that won’t break when dropped. Easy to Price /Sheet grip for wet or dry sanding. Sandpaper Type Part No. Less than 50 Contoured to fit the shape Sheets of a hand and is sized to fit a 1⁄4” sheet of plain backed WP Aluminum Oxide Open Coat “D” 01-26200 $1.75 36 Grit Weight 8 x 11 sandpaper or a 2 3⁄4” wide file paper. It’s coil spring design holds single or SANDPAPER 3M™ multiple sheets equally tight 3M™ Wetordry™ Abrasive Sheet 413Q is an and saves reloading time by ME abrasive sanding paper constructed on a light, stacking up to 4 sheets and A-weight paper backing and features a water- tearing them away as the proof resin bonding to help prevent heat buildup. abrasive wears out. Save The silicon carbide abrasive and waterproof reloading time by using col- backing make this paper an ideal product for ors to indicate grits. Excellent for builders of aircraft, boats, cars, etc. sanding applications such as paint prep, sanding, Yellow ..........................................................P/N 12-00505 ...........$20.50 HA sealer sanding, and solid surface finishing.This Red ..............................................................P/N 12-00506 ...........$19.85 will produce satin-smooth finishes on metal and Green...........................................................P/N 12-00507 ...........$19.95 other doped, lacquered, or enameled surfaces. -

Hand Saw Restoration

NUMBER 175 MARCH 2014 A Journal of Tool Collecting published by CRAFTS of New Jersey Hand Saw Restoration A Presentation by Bob Garay The November CRAFTS Written by Dave Nowicki dle doesn’t make the saw perfect, it can meeting featured a presentation on and does make the saw more comforta- saw restoration by CRAFTS Presi- ble to use. It’s the steel used in these dent Bob Garay. Following is most of the key elements in saws that makes them special. It was highly tempered, the presentation that collectors and woodworkers can use enabling it to hold an edge for a very long time before in the selection and restoration of quality hand saws. resharpening is required. Regardless of any other en- The first rule of thumb is to start with a good hancements it’s the steel that makes a saw. What’s a good saw? In this case we’re talking saw good. With regard to other enhance- about good usable saws. Many times just knowing the ments, just about any saw with a rose- maker of the saw will tell you whether you have a good wood handle is a good indicator of a high saw. According to Bob, when he sees a Disston, a Si- quality saw, where premium materials monds or an Atkins saw he knows it’s a good saw. were used to enhance the product. For When it comes to value, Disston‘s are the ones to look example the Atkins #400 and #401 saws for. They were all made to a consistent high quality had rosewood handles. -

Janitorial 326-348

BACK OF HOUSE Clean & Organize www.wincous.com/product-category/back-of-house JA CARPET ENTRYWAY FLOOR MATS ENTRYWAY FLoor MATS ♦♦Vinyl backing prevents curling/ripping and stays flat ♦♦Carts roll easily over the tapered rubber edge NIT ITEM DESCRIPTION COLOR UOM CASE FMC-310C 3' x 10' Charcoal Each 1 FMC-310U 3' x 10' Burgundy Each 1 FMC-35C 3' x 5' Charcoal Each 1 OR FMC-35U 3' x 5' Burgundy Each 1 BACK OF HOUSE FMC-46C 4' x 6' Charcoal Each 1 FMC-46U 4' x 6' Burgundy Each 1 fmC-310C I Clean & Organize A Tapered, fmC-310U weighted, durable L Lays flat & does not curl/rip Tapered, weighted, with constant foot traffic durable edge ANTI-FATIGUE RUBBERIZED GEL FOAM FLOOR MAT ANTI-SLIP & ANTI-FATIGUE ♦♦Ideal for standing-in-place jobs ♦♦Beveled edges reduce tripping FLoor MATS ♦♦Comfortable and supportive closed-cell foam ♦♦Grease-resistant and waterproof ♦♦1/2" thick ITEM DESCRIPTION COLOR UOM CASE FMG-23K 2' x 3' Black Each 24 Beveled edge FMG-23K 1/2" thick STRAIGHT EdGE NATURAL RUBBER FLOOR MATS ♦♦Anti-slip & anti-fatigue top-grade natural rubber ♦♦Excellent drainage in wet areas ♦♦All straight-edge mats are grease-resistant - use in grease-prone areas to prevent slipping ♦♦Trim to customize size for best fit 3/4" thick ♦♦3/4" thick ITEM DESCRIPTION COLOR UOM CASE Grease-resistant RBMH-35K 3' x 5' Black Each 1 RBMH-35R RBMH-35K RBMH-35R 3' x 5' Red Each 1 RBMH-35K-R 3' x 5', Rolled Black Each 1 RBMH-35R-R 3' x 5', Rolled Red Each 1 Available flat BEVELED EDGE FLOOR MATS or rolled ♦♦Anti-slip & anti-fatigue top-grade natural rubber Red