Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minority Views

MINORITY VIEWS The Minority Members of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence on March 26, 2018 submit the following Minority Views to the Majority-produced "Repo11 on Russian Active Measures, March 22, 2018." Devin Nunes, California, CMAtRMAN K. Mich.J OI Conaw ay, Toxas Pe1 or T. King. New York F,ank A. LoBiondo, N ew Jersey Thom.is J. Roonev. Florida UNCLASSIFIED Ileana ROS·l chtinon, Florida HVC- 304, THE CAPITOL Michnel R. Turner, Ohio Brad R. Wons1 rup. Ohio U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES WASHINGTON, DC 20515 Ou is S1cwart. U1ah (202) 225-4121 Rick Cr.,w ford, Arka nsas P ERMANENT SELECT C OMMITTEE Trey Gowdy, South Carolina 0A~lON NELSON Ellsr. M . S1nfn11ik, Nnw York ON INTELLIGENCE SrAFf. D IREC f()ti Wi ll Hurd, Tcxa~ T11\'10l !IV s. 8 £.R(.REE N At1am 8 . Schiff, Cohforn1a , M tNORllV STAFF OtR ECToq RANKIN G M EMtlER Jorncs A. Himes, Connec1icut Terri A. Sewell, AlabJma AndrC Carso n, lncli.1 na Jacki e Speier, Callfomia Mike Quigley, Il linois E,ic Swalwell, California Joilq u1 0 Castro, T exas De nny Huck, Wash ington P::iul D . Ry an, SPCAl([ R or TH( HOUSE Noncv r c1os1. DEMOC 11t.1 1c Lr:.11.orn March 26, 2018 MINORITY VIEWS On March I, 201 7, the House Permanent Select Commiltee on Intelligence (HPSCI) approved a bipartisan "'Scope of In vestigation" to guide the Committee's inquiry into Russia 's interference in the 201 6 U.S. e lection.1 In announc ing these paramete rs for the House of Representatives' onl y authorized investigation into Russia's meddling, the Committee' s leadership pl edged to unde1take a thorough, bipartisan, and independent probe. -

How Businesses Could Feel the Bern

HOW BUSINESSES COULD FEEL THE BERN A PRIMER ON THE DEMOCRATIC FRONT-RUNNER February 2020 www.monumentadvocacy.com/bizfeelthebern THE FRONT-RUNNER BERNIE 101 As of this week, Senator Bernie Sanders is leading national Democratic THE APPEAL: WHAT POLLING TELLS primary polls, in some cases by double-digit margins. After another early US ABOUT BERNIE’S MOVEMENT state victory in Nevada, he is the betting favorite to become the nominee. Regardless of what comes next in the primary, the grassroots fundraising prowess and early state successes Bernie has shown means he will remain a ANATOMY OF A STUMP SPEECH: formidable force until the Democratic Convention. Dismissed no more than THE CAMPAIGN PROMISES & POLICIES five years ago as a bombastic socialist from a state with fewer than 300,000 voters, Bernie is now leading a national movement that has raised more small dollar donations than any campaign in history, including $25 million in January alone. PROMISES & PAY-FORS: THE BIG- Not unlike President Trump, Bernie uses his massive and loyal following, as TICKET PROPOSALS & WHO WOULD well as his increasingly formidable digital bully pulpit, to target American PAY businesses and announce policies that could soon be the basis for a potential Democratic platform. As businesses work to adjust to the rapidly changing primary dynamics that TARGET PRACTICE: BERNIE’S TOP have catapulted Bernie to frontrunner status, we wanted to provide the basics CORPORATE TARGETS & ATTACKS - a Bernie 101 - to help guide business leaders in understanding the people, organizations and experiences that guide Bernie’s policies and politics. This basic primer also includes many of the Vermont Senator’s favorite targets, ALLIES & ADVISORS: THE ORGS, from companies to institutions to industries. -

September 28, 2017

1 UNCLASSIFIED, COMMITTEE SENSITIVE EXECUTIVE SESSION PERMANENT SELECT COMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE, U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, WASHINGTON, D.C. INTERVIEW OF: BORIS EPSHTEYN Thursday, September 28, 2017 Washington, D.C. The interview in the above matter was held in Room HVC-304, the Capitol, commencing at 11:44 a.m. Present: Representatives Rooney, Schiff, Himes, Speier, Swalwell, and UNCLASSIFIED, COMMITTEE SENSITIVE PROPERTY OF THE UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 2 UNCLASSIFIED, COMMITTEE SENSITIVE Castro. UNCLASSIFIED, COMMITTEE SENSITIVE PROPERTY OF THE UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 3 UNCLASSIFIED, COMMITTEE SENSITIVE Appearances: For the PERMANENT SELECT COMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE: For BORIS EPSHTEYN: CHRISTOPHER AMOLSCH UNCLASSIFIED, COMMITTEE SENSITIVE PROPERTY OF THE UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 4 UNCLASSIFIED, COMMITTEE SENSITIVE Good morning. This is an unclassified, committee sensitive, transcribed interview of Boris Epshteyn. Thank you for speaking to us today. For the record, I am a staff member of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence. Others present today will introduce themselves when they speak. Before we begin, I have a security reminder. If you haven't left your electronics outside, please do at this time. I'm sure you've all left your electronics outside. MR. EPSHTEYN: Yes. That includes BlackBerrys, iPhones, Androids, tablets, iPads, or e-readers, laptop, iPods, MP3 players, recording devices, cameras, wireless headsets, pagers, and any other type of Bluetooth wristbands or watches. I also want to state a few things for the record. The questioning will be conducted by members and staff during their allotted time period. Some questions may seem basic, but that is because we need to clearly establish facts and understand the situation. -

VOTING IS the ONE THING LEFT on MY BUCKET LIST.” –ACLU Activist Cat Castaneda

FOR PASSIONATE GUARDIANS OF INDIVIDUAL RIGHTS AND LIBERTIES SUMMER 2018 VOTING IS THE ONE THING LEFT ON MY BUCKET LIST.” –ACLU Activist Cat Castaneda ACLU.ORG LEAVE A GIFT of Hope for Today and Tomorrow. PHOTO: Getty Images PHOTO: The Crankstart Foundation has issued a challenge to all ACLU supporters: You can trigger an immediate cash donation, matching up to 10% of your future gift, by including the ACLU in your will. Your commitment will help us defend democracy today and protect civil liberties tomorrow. For more info, visit aclu.org/jointhechallenge or fill out the enclosed reply envelope. BULLHORN AFTER NEARLY TWO YEARS OF CHAOS in the Trump administration, all eyes are on this fall’s critical midterm elections, which have the potential to reshape the political landscape for the next decade. With all 435 seats in the House of Representatives, 35 in the Senate, and 36 governors’ chairs at stake, this next wave of lawmakers will have a say in longstanding legal and legislative battles over issues such as reproductive freedom, immigrants’ rights, criminal justice reform, and of course, voting rights. The ACLU has long been known for waging these battles in court and in legislatures. Now we’ve powered up a new, nonpartisan electoral operation aimed at educating voters about where candidates stand on defending crucial civil liberties. In this issue, I team up with ACLU Political Director Faiz Shakir to report on the ACLU’s $25 million investment in voter education and activation (“Vote for Your Rights,” p. 24). To be clear: We are staunchly nonpartisan, we don’t support or oppose any candidates for elected or appointed office, we’re not telling voters how to vote, and we’re not registering voters. -

The Growth of Sinclair's Conservative Media Empire – the New Yorker

1/15/2019 The Growth of Sinclair’s Conservative Media Empire | The New Yorker Annals of Media October 22, 2018 Issue The Growth of Sinclair’s Conservative Media Empire The company has achieved formidable reach by focussing on small markets where its TV stations can have a big inuence. By Sheelah Kolhatkar Sinclair has largely evaded the kind of public scrutiny given to its more famous competitor, Fox News. Illustration by Paul Sahre; photograph from Blend Images / ColorBlind Images / Getty https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/10/22/the-growth-of-sinclairs-conservative-media-empire 1/19 1/15/2019 The Growth of Sinclair’s Conservative Media Empire | The New Yorker 0:00 / 45:27 Audio: Listen to this article. To hear more, download the Audm iPhone app. auren Hills knew that she wanted to be a news broadcaster in the fourth grade, when a veteran television anchor L came to speak at her school’s career day. “Any broadcast journalist will tell you something very similar,” Hills said recently, when I met her. “For a majority of us, we knew at a very young age.” She became a sports editor at her high-school newspaper, in Wellington, Florida, near Palm Beach, and then attended the journalism program at the University of Florida, in Gainesville. Before graduation, she began sending résumé tapes to dozens of TV stations in small markets, hoping for an offer. Hills showed me the list she had used in her search. Written in pen in the margin was a note to herself: “You can do it!!!!” Hills was hired as a general-assignment reporter at a channel in West Virginia, in 2005, and began covering what she called “typical small-market news”—city-council meetings and local football games. -

Court Filing

Case 1:19-gj-00048-BAH Document 20 Filed 09/13/19 Page 1 of 46 THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ____________________________________ ) IN RE: ) ) APPLICATION OF THE COMMITTEE ) Civil Action No. 1:19-gj-00048-BAH ON THE JUDICIARY, U.S. HOUSE OF ) REPRESENTATIVES, FOR AN ORDER ) AUTHORIZING THE RELEASE OF ) CERTAIN GRAND JURY MATERIALS ) DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE’S RESPONSE TO THE APPLICATION OF THE HOUSE JUDICIARY COMMITTEE FOR AN ORDER AUTHORIZING RELEASE OF CERTAIN GRAND JURY MATERIALS JOSEPH H. HUNT Assistant Attorney General JAMES M. BURNHAM Deputy Assistant Attorney General ELIZABETH J. SHAPIRO CRISTEN C. HANDLEY Attorneys, Federal Programs Branch U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Division 1100 L Street NW Washington, DC 20005 Tel: (202) 514-5302 Fax: (202) 616-8460 Counsel for Department of Justice Case 1:19-gj-00048-BAH Document 20 Filed 09/13/19 Page 2 of 46 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................ 7 A. Procedural Background ........................................................................................... 7 B. Statutory Background ............................................................................................. 9 ARGUMENT ............................................................................................................................... -

The Trailer: Biden Invites the Left In

The Washington Post Politics Analysis The Trailer: Biden invites the left in By David Weigel In this edition: Biden's offer to the left, good news for Republicans from California, and a good poll for the president that's also a bad poll for the president. You only get one chance to name a “-gate” after a politician, so you've got to make it count. This is The Trailer. The Democratic primary had been over for weeks when Varshini Prakash, the 26-year-old president of the Sunrise Movement, first got the offer. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and former vice president Joe Biden had agreed to create “unity task forces,” one of them focused entirely on climate change. Would Prakash, who helped popularize the Green New Deal, want to join? She had to think about it. “We sort of conferred with movement leaders, and with [New York Rep.] Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez's team,” Prakash said in an interview. “We wanted to move in lockstep. And in more recent interviews and conversations, I'd seen Biden step up the way that he talks about the climate crisis.” Prakash and Ocasio-Cortez both decided to join the climate group, one of six announced Tuesday. At the exact moment that the Trump campaign is launching new ads that portray Biden as a dangerous left- winger, the Democrat's campaign was putting prominent left-wing activists into new roles, with a one- month mandate to meet and help shape his policies. Biden, who had ignored many activists' litmus tests and won anyway, had decided to invite some into the tent. -

Boris Epshteyn

WORLDWIDE SPEAKERS GROUP LLC YOUR GLOBAL PARTNER IN THOUGHT LEADERSHIP BORIS EPSHTEYN Boris Epshteyn is the Chief PoLitical Analyst for SincLair Broadcast Group, one of the Largest and most diversified teLevision broadcasting companies in the country. Boris hosts the “Bottom Line with Boris” segments across SincLair’s pLatforms, providing insight into issues ranging from foreign poLicy and national security to tax reform and healthcare. PreviousLy, Boris served as Special Assistant to President Trump and Assistant Communications Director at the White House. Boris managed strategy for media appearances by Administration representatives, as weLL as coordinated interviews of, and provided briefings to, top Administration officials, incLuding the President and Vice President of the United States. Boris assisted with, and advised on, White House communications strategy across alL subjects and appeared as an on-air spokesman for the Administration across national and Local outlets. PreviousLy, Boris served as the Director of Communications for the Presidential Inaugural Committee where he directed communications strategy and impLementation for the inauguration of President Donald J. Trump and Vice President MichaeL R. Pence on January 20th, 2017. As a Senior Advisor to the Trump – Pence 2016 Presidential Campaign, Boris concentrated on communications messaging and strategy. He managed surrogate messaging, prepared and distributed talking points and briefed President (then – candidate) Trump and Vice President (then – candidate) Pence as weLL as campaign senior staff and surrogates. Boris also pLanned, produced and anchored the “Trump Tower Live” program, which aired on the Facebook Live pLatform, and conducted on air interviews with President (then – candidate) Donald Trump, Trump famiLy members and other key surrogates. -

X ARLENE DELGADO, Civil Case No.: 19-Cv-11764

Case 1:19-cv-11764 Document 1 Filed12/23/19 Page 1 of 16 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ----------------------------------------------------x ARLENE DELGADO, Civil Case No.: 19-cv-11764 PLAINTIFF DEMANDS Plaintiff, A TRIAL BY JURY -against- COMPLAINT DONALDJ. TRUMPFORPRESIDENT,INC., TRUMPFORAMERICA,INC., SEANSPICER,individually, REINCEPRIEBUS,individually, STEPHENBANNON,individually, Defendants. ------------------------------------------------------x Plaintiff,ARLENE DELGADO,(hereinafter referred to as “A.J. Delgado” or “Plaintiff”), by and through her attorneys, DEREK SMITH LAW GROUP, PLLC, hereby complains of Defendants, DONALD J. TRUMP FOR PRESIDENT, INC., (hereinafter referred to as the “Trump Campaign” or “Campaign”),TRUMP FOR AMERICA, INC.,(hereinafter referred to as the “Transition Organization” or “TFA”) SEAN SPICER, individually, REINCE PRIEBUS, individually and STEPHEN BANNON, individually (together, the “Campaign Directors” or “Transition Directors”) and all collectively referred to as “Defendants,” upon information and belief, as follows: NATUREOF CASE Plaintiff, ARLENE DELGADO, complains pursuant to the common law of the state of New York, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as codified, 42 U.S.C.§§ 2000e to 2000e- 17 (amended in 1972, 1978 and by the Civil Rights Act of 1991, Pub. L. No. 102-166 (“Title 1 Case 1:19-cv-11764 Document 1 Filed12/23/19 Page 2 of 16 VII”), the Administrative Code of the City of New York and the laws of the State of New York, based upon the supplemental jurisdiction of this Court pursuant to United Mine Workers of America v. Gibbs, 383 U.S. 715 (1966), and 28 U.S.C. §1367 seeking declaratory relief and damages to redress the injuries Plaintiff has suffered as a result of inter alia, a breach of contract, tortious interference with economic advantage, pregnancy discrimination, sex and gender discrimination,hostile work environment and retaliation by Defendants. -

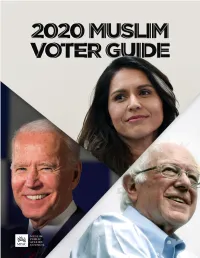

2020-Muslim-Voter-Guide.Pdf

Table of Contents About the Guide .......................................................................................................................... 3 THE ISSUES Civil Rights and Civil Liberties .................................................................................4 Climate Change/Environment ................................................................................. 7 Criminal Justice Reform .............................................................................................. 9 Economy/Jobs .................................................................................................................11 Education ...........................................................................................................................13 Foreign Policy .................................................................................................................15 Gun Reform ......................................................................................................................18 Healthcare ....................................................................................................................... 20 Immigration .....................................................................................................................22 Engagement with American Muslims ................................................................24 About MPAC ................................................................................................................................26 ABOUT THE -

Political Norms, Constitutional Conventions, and President Donald Trump

Indiana Law Journal Volume 93 Issue 1 The Future of the U.S. Constitution: A Article 11 Symposium Winter 2018 Political Norms, Constitutional Conventions, and President Donald Trump Neil S. Siegel Duke Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Law and Politics Commons, and the President/Executive Department Commons Recommended Citation Siegel, Neil S. (2018) "Political Norms, Constitutional Conventions, and President Donald Trump," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 93 : Iss. 1 , Article 11. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol93/iss1/11 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Political Norms, Constitutional Conventions, and President Donald Trump NEIL S. SIEGEL* My big worry is not simply that formal institutions have been eroded, but that the informal norms that underpin them are even more important and even more fragile. Norms of transparency, conflict of interest, civil discourse, respect for the opposition and freedom of the press, and equal treatment of citizens are all consistently undermined, and without these the formal institutions become brittle.1 In the wake of the 2016 elections, I was driving near my home in Durham, North Carolina, with my eldest daughter, Sydney. She was only twelve years of age at the time, but she is an old soul. -

House Section

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 115 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 164 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, MAY 8, 2018 No. 74 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was The reforms in the Every Student ney Lewis, a respected member of the called to order by the Speaker pro tem- Succeeds Act enable charter schools to Gila River Indian Community, a loving pore (Mr. MARSHALL). serve more students and allow States father, and a committed Arizonan who f to support new, high-quality charter made a career fighting for water rights schools to address the growing demand for Indian Tribes across the country. DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO for these schools. And the demand is When he was a boy, Rod, as his TEMPORE high. Currently, 5 million students are friends called him, remembered watch- The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- awaiting their chance to attend. Char- ing his family survive droughts that fore the House the following commu- ter schools offer American families the destroyed crops, and he would listen to nication from the Speaker: right to choose what environment is stories about the damming of the Gila best for their child. It is clear that par- River, which gave life to those who WASHINGTON, DC, lived in the region. May 8, 2018. ents and students want this choice Mr. Lewis served his country in the I hereby appoint the Honorable ROGER W. available to them, and they deserve to United States Army infantry, becom- MARSHALL to act as Speaker pro tempore on have it.