Kingswood and Mangotsfield

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wotton Under Edge

SELECT ROLL 82 GLOUCESTERSHIRE Indented extract made on the 10th day of May in the 23rd year of the reign of our lady Elizabeth, by the grace of God, queen of England, France & Ireland, defender of the faith, etc. Of all sums of money chargeable on anyone living within the boundary of the hundreds of Berkeley, Grumbald's Ash, Thornbury, Henbury, Pucklechurch and Barton in the county aforesaid, at the first payment of the subsidy from the laity granted by act of the parliament held at Westminster in the 23rd year of the reign of the said lady queen, ratified, assessed & taxed before us, Sir Thomas Porter & Thomas Throckmorton, esq., by virtue of the said lady queen's commission, together with others directed in that matter; whereof one part is to be handed over and delivered to Edward Trotman, gent., the head or chief collector of the hundreds aforesaid, named and appointed for the levying of the sums specified in the same extract [which are] to be paid for the work and use of the said lady queen; the other part of the aforesaid extract is to be handed over and delivered to the barons of the exchequer of the said lady queen, according to the tenor of the said act of parliament, to be kept together with the obligatory document of the said collector annexed to these presents certified under our seals abovementioned, which certain sums, together with names and surnames of anyone chargeable within the hundreds & boundaries aforesaid, with their place of abode, follows after. LAND GOODS ASSESSMENT £ s d BERKELEY HUNDRED Berkeley William BUTCHER £3 8 0 Richard BUTCHER 40s 5 4 Richard HIX 40s 5 4 Margaret HIX, infant £3 8 0 Thomas NEALE £5 8 4 William BOWER £4 6 8 Maurice TEISOME £3 5 0 Robert TOWNSEND £3 5 0 Maurice ATWOOD £3 5 0 Richard HERRINGE £3 5 0 TOTAL £3 1s 8d Arlingham Paid Jane WESTWARD £5 13 4 Richard YATE, gent. -

Ms Kate Coggins Sent Via Email To: Request-713266

Chief Executive & Corporate Resources Ms Kate Coggins Date: 8th January 2021 Your Ref: Our Ref: FIDP/015776-20 Sent via email to: Enquiries to: Customer Relations request-713266- Tel: (01454) 868009 [email protected] Email: [email protected] Dear Ms Coggins, RE: FREEDOM OF INFORMATION ACT REQUEST Thank you for your request for information received on 16th December 2020. Further to our acknowledgement of 18th December 2020, I am writing to provide the Council’s response to your enquiry. This is provided at the end of this letter. I trust that your questions have been satisfactorily answered. If you have any questions about this response, then please contact me again via [email protected] or at the address below. If you are not happy with this response you have the right to request an internal review by emailing [email protected]. Please quote the reference number above when contacting the Council again. If you remain dissatisfied with the outcome of the internal review you may apply directly to the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO). The ICO can be contacted at: The Information Commissioner’s Office, Wycliffe House, Water Lane, Wilmslow, Cheshire, SK9 5AF or via their website at www.ico.org.uk Yours sincerely, Chris Gillett Private Sector Housing Manager cc CECR – Freedom of Information South Gloucestershire Council, Chief Executive & Corporate Resources Department Customer Relations, PO Box 1953, Bristol, BS37 0DB www.southglos.gov.uk FOI request reference: FIDP/015776-20 Request Title: List of Licensed HMOs in Bristol area Date received: 16th December 2020 Service areas: Housing Date responded: 8th January 2021 FOI Request Questions I would be grateful if you would supply a list of addresses for current HMO licensed properties in the Bristol area including the name(s) and correspondence address(es) for the owners. -

Warmley Forest Park Heritage Walks

Points of Interest Points of Interest continued A Warmley The signal box here is very well G Bristol This very popular 13 mile path, open Station preserved. The sidings here were for and Bath to both cyclists and walkers was coal and red ochre destined for the Railway constructed on the track bed of the works at Wick. The station itself was Path former Midland Railway which closed declared redundant in 1965. to passenger traffic towards the end of the 1960s. B Midland This pub was formerly known as the Spinner Midland Railway Inn and was popular Public with local workers. The Warmley Within South Gloucestershire lie many hidden treasures House Crown Colliery was adjacent to the that have helped shape the landscape as we know it today. Points of Interest 4General pub. START/FINISH POINT Natural, industrial and cultural forces have played a part in At Warmley Station, making up the local environment that we live and work in. C Evidence The peaceful surroundings of Warmley Station Close, off High Warmley Forest Park lies on the site of former of Forest Park as it is now contrasts Wild Roots is an innovative Heritage Lottery Funded, three Street, Warmley (A420). extensive clay quarrying. Until recently it lay derelict, quarrying greatly with the site fifty or more year project that is working with local communities to This is a disused but is now popular with local residents for walks and for clay years ago when clay was quarried conserve, enhance and celebrate the natural and cultural station on what is now runs. -

NOTICE of ELECTION Election of Parish Councillors

NOTICE OF ELECTION South Gloucestershire Council Election of Parish Councillors for the Parishes listed below Number of Parish Councillors to Number of Parish Councillors to Parishes Parishes be elected be elected Acton Turville Five Marshfield Nine Almondsbury, Almondsbury Four Oldbury-on-Severn Seven Almondsbury, Compton Two Oldland, Cadbury Heath Seven Almondsbury, Cribbs Causeway Seven Oldland, Longwell Green Seven Alveston Eleven Oldland, Mount Hill One Aust Seven Olveston Nine Badminton Seven Patchway, Callicroft Nine Bitton, North Common Six Patchway, Coniston Six Bitton, Oldland Common Four Pilning & Severn Beach, Pilning Four Bitton, South Four Pilning & Severn Beach, Severn Six Beach Bradley Stoke, North Six Pucklechurch Nine Bradley Stoke, South Seven Rangeworthy Five Bradley Stoke, Stoke Brook Two Rockhampton Five Charfield Nine Siston, Common Three Cold Ashton Five Siston, Rural One Cromhall Seven Siston, Warmley Five Dodington, North East Four Sodbury, North East Five Dodington, North West Eight Sodbury, Old Sodbury Five Dodington, South Three Sodbury, South West Five Downend & Bromley Heath, Downend Ten Stoke Gifford, Central Nine Downend & Bromley Heath, Staple Hill Two Stoke Gifford, University Three Doynton Five Stoke Lodge and the Common Nine Dyrham & Hinton Five Thornbury, Central Three Emersons Green, Badminton Three Thornbury, East Three Emersons Green, Blackhorse Three Thornbury, North East Four Emersons Green, Emersons Green Seven Thornbury, North West Three Emersons Green, Pomphrey Three Thornbury, South Three -

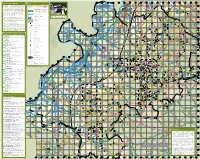

Places of Interest How to Use This Map Key Why Cycle?

76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 How to use this map Key The purpose of this map is to help you plan your route Cycleability gradations, in increasing difficulty 16 according to your own cycling ability. Traffic-free paths and pavements are shown in dark green. Roads are 1 2 3 4 5 graded from ‘quieter/easier’ to ‘busier/more difficult’ Designated traffic-free cycle paths: off road, along a green, to yellow, to orange, to pink, to red shared-used pavements, canal towpaths (generally hard surfaced). Note: cycle lanes spectrum. If you are a beginner, you might want to plan marked on the actual road surface are not 15 your journey along mainly green and yellow roads. With shown; the road grading takes into account the existence and quality of a cycle lane confidence and increasing experience, you should be able to tackle the orange roads, and then the busier Canal towpath, usually good surface pinky red and darker red roads. Canal towpath, variable surface Riding the pink roads: a reflective jacket Our area is pretty hilly and, within the Stroud District can help you to be seen in traffic 14 Useful paths, may be poorly surfaced boundaries, we have used height shading to show the lie of the land. We have also used arrows > and >> Motorway 71 (pointing downhill) to mark hills that cyclists are going to find fairly steep and very steep. Pedestrian street 70 13 We hope you will be able to use the map to plan One-way street Very steep cycling routes from your home to school, college and Steep (more than 15%) workplace. -

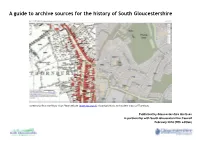

A Guide to Archive Sources for the History of South Gloucestershire

A guide to archive sources for the history of South Gloucestershire Screenshot from the Know Your Place website (www.kyp.org.uk) showing historic and modern maps of Thornbury Published by Gloucestershire Archives in partnership with South Gloucestershire Council February 2018 (fifth edition) Table of contents How to use this guide .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Introduction .............................................................................................................................................................................................................. 8 Archive provision in South Gloucestershire .......................................................................................................................................................... 8 The City of Bristol and its record keeping ............................................................................................................................................................. 9 The county of Gloucestershire and its recordkeeping ........................................................................................................................................ 12 Church records .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 14 Barton -

South Gloucestershire Council Conservative Group

COUNCIL SIZE SUBMISSION South Gloucestershire South Gloucestershire Council Conservative Group. February 2017 Overview of South Gloucestershire 1. South Gloucestershire is an affluent unitary authority on the North and East fringe of Bristol. South Gloucestershire Council (SGC) was formed in 1996 following the dissolution of Avon County Council and the merger of Northavon District and Kingswood Borough Councils. 2. South Gloucestershire has around 274,700 residents, 62% of which live in the immediate urban fringes of Bristol in areas including Kingswood, Filton, Staple Hill, Downend, Warmley and Bradley Stoke. 18% live in the market towns of Thornbury, Yate, and Chipping Sodbury. The remaining 20% live in rural Gloucestershire villages such as Marshfield, Pucklechurch, Hawkesbury Upton, Oldbury‐ on‐Severn, Alveston, and Charfield. 3. South Gloucestershire has lower than average unemployment (3.3% against an England average of 4.8% as of 2016), earns above average wages (average weekly full time wage of £574.20 against England average of £544.70), and has above average house prices (£235,000 against England average of £218,000)1. Deprivation 4. Despite high employment and economic outputs, there are pockets of deprivation in South Gloucestershire. Some communities suffer from low income, unemployment, social isolation, poor housing, low educational achievement, degraded environment, access to health services, or higher levels of crime than other neighbourhoods. These forms of deprivation are often linked and the relationship between them is so strong that we have identified 5 Priority Neighbourhoods which are categorised by the national Indices of Deprivation as amongst the 20% most deprived neighbourhoods in England and Wales. These are Cadbury Heath, Kingswood, Patchway, Staple Hill, and west and south Yate/Dodington. -

Communications Roads Cheltenham Lies on Routes Connecting the Upper Severn Vale with the Cotswolds to the East and Midlands to the North

DRAFT – VCH Gloucestershire 15 [Cheltenham] Communications Roads Cheltenham lies on routes connecting the upper Severn Vale with the Cotswolds to the east and Midlands to the north. Several major ancient routes passed nearby, including the Fosse Way, White Way and Salt Way, and the town was linked into this important network of roads by more local, minor routes. Cheltenham may have been joined to the Salt Way running from Droitwich to Lechlade1 by Saleweistrete,2 or by the old coach road to London, the Cheltenham end of which was known as Greenway Lane;3 the White Way running north from Cirencester passed through Sandford.4 The medieval settlement of Cheltenham was largely ranged along a single high street running south-east and north-west, with its church and manorial complex adjacent to the south, and burgage plots (some still traceable in modern boundaries) running back from both frontages.5 Documents produced in the course of administering the liberty of Cheltenham refer to the via regis, the king’s highway, which is likely to be a reference to this public road running through the liberty. 6 Other forms include ‘the royal way at Herstret’ and ‘the royal way in the way of Cheltenham’ (in via de Cheltenham). Infringements recorded upon the via regis included digging and ploughing, obstruction with timbers and dungheaps, the growth of trees and building of houses.7 The most important local roads were those running from Cheltenham to Gloucester, and Cheltenham to Winchcombe, where the liberty administrators were frequently engaged in defending their lords’ rights. Leland described the roads around Cheltenham, Gloucester and Tewkesbury as ‘subject to al sodeyne risings of Syverne, so that aftar reignes it is very foule to 1 W.S. -

948 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

948 bus time schedule & line map 948 Pucklechurch - Oldland Common View In Website Mode The 948 bus line (Pucklechurch - Oldland Common) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Oldland Common: 7:45 AM (2) Pucklechurch: 3:22 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 948 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 948 bus arriving. Direction: Oldland Common 948 bus Time Schedule 35 stops Oldland Common Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday Not Operational Maple Walk, Pucklechurch Holly Close, Pucklechurch Tuesday 7:45 AM Kestrel Drive, Pucklechurch Wednesday 7:45 AM Goldƒnch Way, Pucklechurch Thursday Not Operational Oak Tree Avenue, Pucklechurch Friday Not Operational The Fleur De Lys, Pucklechurch Saturday Not Operational 4 Westerleigh Road, Pucklechurch Homeƒeld Road, Pucklechurch B4465, Pucklechurch 948 bus Info Dennisworth Farm, Pucklechurch Direction: Oldland Common Stops: 35 Siston Lane, Siston Trip Duration: 41 min Line Summary: Maple Walk, Pucklechurch, Kestrel Sainsburys, Emersons Green Drive, Pucklechurch, Goldƒnch Way, Pucklechurch, The Fleur De Lys, Pucklechurch, Homeƒeld Road, Glevum Close, Emersons Green Pucklechurch, Dennisworth Farm, Pucklechurch, Siston Lane, Siston, Sainsburys, Emersons Green, Beck Close, Emersons Green Glevum Close, Emersons Green, Beck Close, Emersons Green, Johnson Road, Emersons Green, Johnson Road, Emersons Green Shackel Hendy Mews, Emersons Green, Wheelers Patch, Emersons Green, Mangotsƒeld Fc, Johnson Road, Bristol Mangotsƒeld, St James -

Paying for the Party

PX_PARTY_HDS:PX_PARTY_HDS 16/4/08 11:48 Page 1 Paying for the Party Myths and realities in British political finance Michael Pinto-Duschinsky edited by Roger Gough Policy Exchange is an independent think tank whose mission is to develop and promote new policy ideas which will foster a free society based on strong communities, personal freedom, limited government, national self-confidence and an enterprise culture. Registered charity no: 1096300. Policy Exchange is committed to an evidence-based approach to policy development. We work in partnership with aca- demics and other experts and commission major studies involving thorough empirical research of alternative policy out- comes. We believe that the policy experience of other countries offers important lessons for government in the UK. We also believe that government has much to learn from business and the voluntary sector. Tru, stees Charles Moore (Chairman of the Board), Theodore Agnew, Richard Briance, Camilla Cavendish, Robin Edwards, Richard Ehrman, Virginia Fraser, Lizzie Noel, George Robinson, Andrew Sells, Tim Steel, Alice Thomson, Rachel Whetstone PX_PARTY_HDS:PX_PARTY_HDS 16/4/08 11:48 Page 2 About the author Dr Michael Pinto-Duschinsky is senior Nations, the European Union, Council of research fellow at Brunel University and a Europe, Commonwealth Secretariat, the recognised worldwide authority on politi- British Foreign and Commonwealth cal finance. A former fellow of Merton Office and the Home Office. He was a College, Oxford, and Pembroke College, founder governor of the Westminster Oxford, he is president of the International Foundation for Democracy. In 2006-07 he Political Science Association’s research was the lead witness before the Committee committee on political finance and politi- on Standards in Public Life in its review of cal corruption and a board member of the the Electoral Commission. -

The Bristol Medico - Chirurgical Journal

The Bristol Medico - Chirurgical Journal A JOURNAL OF THE MEDICAL SCIENCES FOR THE WEST OF ENGLAND AND SOUTH WALES. PUBLISHED UNDER THE AUSPICES OF THE BRISTOL MEDICO-CHIRURGICAL SOCIETY. EDITOR : J. A. NIXON, C.M.G., M.D., F.R.C.P. WITH WHOM ARE ASSOCIATED E. W. HEY GROVES, D.Sc., M.S., F.R.C.S. A. E. ILES, O.B.E., M.B., B.S., F.R.C.S. A. RENDLE SHORT, M.D., B.S., B.Sc., F.R.C.S. E. WATSON-WILLIAMS, M.C., Ch.M., F.R.C.S., Assistant Editor. EDITORIAL SECRETARY : A. L. FLEMMING, M.B., Ch.B. "Sctte est ncBclre, nfai (6 mc Sctve alius aciret." VOL. LIV. BRISTOL: J. W. ARROWSMITH LTD. London : J. W. Arrowsmith (London) Ltd. Contents of Vol. LIV Page The Evolution of a Casualty Clearing Station on the Western Front. By Richard C. Clarke, O.B.E., M.B., F.R.C.P. .. 1 ^lie Enlarged Prostate from the point of view of Practitioner and Surgeon. By C. Ferrier Walters, F.R.C.S. .. 21 J-lie Therapeutic Value of Altitude. By Bernard Hudson, M.D., M.R.C.P 35 -The Role of the Central Nervous System in Disease : Recent Experi- mental Work in the U.S.S.R. By F. Bodman, M.D. 41 ^he Carey Coombs Memorial Lecture on the Pathology and Surgical Treatment of Cardiac Ischsemia. By Laurence O'Shaughnessy, F.R.C.S 109 S?m.e Reflections on Research in Medicine. By F. J. Poynton, M.D., F.R.C.P 127 Spinal Anaesthesia. -

Draft Local Transport Plan Consultation Document 1

Gloucestershire’s Draft Draft Local Transport Plan Local Transport Plan Consultation | DOCUMENT 1 2015-31 Including the following strategy documents: A resilient transport network that enables sustainable economic growth • Overarching Strategy • CPS4 – South Cotswold Connecting Places Strategy providing door to door travel choices • CPS1 - Central Severn Vale Connecting Places Strategy • CPS5 – Stroud Connecting Places Strategy • CPS2 - Forest of Dean Connecting Places Strategy • CPS6 – Tewkesbury Connecting Places Strategy • CPS3 – North Cotswold Connecting Places Strategy This page is intentionally blank Draft Local Transport Plan consultation document 1 This document combines the following separate strategies into one document to aid the consultation process. Overarching Strategy CPS1 - Central Severn Vale Connecting Places Strategy CPS2 - Forest of Dean Connecting Places Strategy CPS3 – North Cotswold Connecting Places Strategy CPS4 – South Cotswold Connecting Places Strategy CPS5 – Stroud Connecting Places Strategy CPS6 – Tewkesbury Connecting Places Strategy This page is intentionally blank Gloucestershire’s Draft Local Transport Plan Overarching 2015-31 Strategy A resilient transport network that enables sustainable economic growth providing door to door travel choices Gloucestershire’s Draft Local Transport Plan - Overarching Strategy Local Transport Plan This strategy acts as guidance for anybody requiring information on how the county council will manage the transport network in Gloucestershire Overarching Strategy Document