Historical Overview of the Woodlawn Quaker Meeting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Fox's Footsteps: Planning 1652 Country Quaker Pilgrimages 2019

in fox's footsteps: planning 1652 country quaker pilgrimages 2019 Why come “If you are new to Quakerism, there can be no on a better place to begin to explore what it may mean Quaker for us than the place in which it began. pilgrimage? Go to the beautiful Meeting Houses one finds dotted throughout the Westmorland and Cumbrian countryside and spend time in them, soaking in the atmosphere of peace and calm, and you will feel refreshed. Worship with Quakers there and you may begin to feel changed by the experience. What you will find is a place where people took the demands of faith seriously and were transformed by the experience. In letting themselves be changed, they helped make possible some of the great changes that happened to the world between the sixteenth and the eighteenth centuries.” Roy Stephenson, extracts from ‘1652 Country: a land steeped in our faith’, The Friend, 8 October 2010. 2 Swarthmoor Hall organises two 5 day pilgrimages every year Being part of in June/July and August/September which are open to an organised individuals, couples, or groups of Friends. ‘open’ The pilgrimages visit most of the early Quaker sites and allow pilgrimage individuals to become part of an organised pilgrimage and worshipping group as the journey unfolds. A minibus is used to travel to the different sites. Each group has an experienced Pilgrimage Leader. These pilgrimages are full board in ensuite accommodation. Hall Swarthmoor Many Meetings and smaller groups choose to arrange their Planning own pilgrimage with the support of the pilgrimage your own coordination provided by Swarthmoor Hall, on behalf of Britain Yearly Meeting. -

Nomination Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: Woodlawn Cultural Landscape Historic District Other names/site number: DHR File No.: 029-5181 Name of related multiple property listing: N/A (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: Bounded by Old Mill Rd, Mt Vernon Memorial Hwy, Fort Belvoir, and Dogue Creek City or town: Alexandria State: VA County: Fairfax Not For Publication: N/A Vicinity: X ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional -

MT VERNON SQUARE Fairfax County

Richmond Highway (Route 1) & Arlington Drive Alexandria, VA 22306 MT VERNON SQUARE Fairfax County SITE MT. VERNON SQUARE ( 5 2 0 3 1 ,00 8 A D T 0 ) RETAIL FOR SUBLEASE JOIN: • Size: 57,816 SF (divisible). • Term: Through 4/30/2026 with 8, five-year options to renew. • Uses Considered: ALL uses considered including grocery. • Mt. Vernon Square is located on heavily traveled Richmond Highway (Route 1) with over 53,000 vehicles per day. ( 5 2 • This property has0 3 a total of 70,617 SF of retail that includes: M&T Bank, Ledo Pizza, and Cricket Wireless. 1 ,00 8 A MT. VERNON D T 0 PLAZA ) Jake Levin 8065 Leesburg Pike, Suite 700 [email protected] Tysons, VA 22182 202-909-6102 klnb.com Richmond Hwy Richmond 6/11/2019 PROPERTY CAPSULE: Retail + Commercial Real Estate iPad Leasing App, Automated Marketing Flyers, Site Plans, & More 1 Mile 3 Miles 5 Miles 19,273 115,720 280,132 Richmond Highway (Route 1) & Arlington6,689 Drive43,290 Alexandria,115,935 VA 22306 $57,205 $93,128 $103,083 MT VERNON SQUARE Fairfax County DEMOGRAPHICS | 2018: 1-MILE 3-MILE 5-MILE Population 19,273 115,720 280,132 Daytime Population 15,868 81,238 269,157 Households 6,689 43,290 15,935 Average HH Income SITE $84,518 $127,286 $137,003 CLICK TO DOWNLOAD DEMOGRAPHIC REPORT 1 MILE TRAFFIC COUNTS | 2019: Richmond Hwy (Route 1) Arlington Dr. 53,000 ADT 3 MILE 5 MILE LOCATION & DEMOGRAPHICS Jake Levin 8065 Leesburg Pike, Suite 700 [email protected] Tysons, VA 22182 202-909-6102 klnb.com https://maps.propertycapsule.com/map/print 1/2 Richmond Highway (Route 1) & Arlington Drive -

Woodlawn Historic District in Fairfax Co VA

a l i i Woodlawn was a gift from George Washington In 1846, a group of northern Quakers purchased n a i r g to his step-granddaughter, Eleanor “Nelly” the estate. Their aim was to create a farming T r i e Custis, on her marriage to his nephew Lawrence community of free African Americans and white V , TION ag A y t V i t Lewis. Washington selected the home site settlers to prove that small farms could succeed r e himself, carving nearly 2,000 acres from his with free labor in this slave-holding state. oun H Mount Vernon Estate. It included Washington’s C ac x Gristmill & Distillery (below), the largest producer The Quakers lived and worshipped in the a f om Woodlawn home until their more modest r t of whiskey in America at the time. o ai farmhouses and meetinghouse (below) were F P Completed in 1805, the Woodlawn Home soon built. Over forty families from Quaker, Baptist, TIONAL TRUST FOR HISTORIC PRESER became a cultural center. The Lewises hosted and Methodist faiths joined this diverse, ”free- many notable guests, including John Adams, labor” settlement that fl ourished into the early Robert E. Lee and the Marquis de Lafayette. 20th century. TESY OF THE NA COUR t Woodlawn became the fi rst property c of The National Trust for Historic Preservation in 1951. This private non- ri profi t is dedicated to working with t communities to save historic places. s i When construction of Route 66 threatened the nearby Pope-Leighey House (below), designed by renowned D architect Frank Lloyd Wright, the c National Trust relocated this historic home to Woodlawn. -

Ancestry of Glendon Jean Starr Group Five

Copyright 2014 Linda Sparks Starr ANCESTRY OF GLENDON JEAN STARR GROUP FIVE Edward Pate and Mary (Crawford) Eleanor (Pate) Clark Comstock Hambleton was the daughter of Edward Pate, born February 25, 1766 in Bedford County and Mary Crawford, born November 18, 1771 in neighboring Botetourt (pronounced "bought a tot") County, Virginia. We know very little about the childhood of either Edward or Mary. We can assume their life wasn't all that much different from others who grew up in the shadow of the Blue Ridge during the Revolutionary War years. Both fathers served with local militia companies, requiring them to be away from the family for three to six months at a time. Edward by then was old enough to take on the chores usually performed by his father and Mary would have been expected to keep her younger siblings from harm's way. Once the war was over dinner table conversation likely revolved around discussion of crop yields and the latest news from Kentucky. Edward and Mary married April 6, 1789 in Botetourt County and their first children, including your Eleanor, were born there. For them the decision to move west wasn't as difficult as it could have been. They were joining others -- her parents, several of their siblings and numerous friends. This group settled in Hardin County, but ended up in Ohio and Breckinridge when those two counties were carved out of the larger one. The first Court of the Quarter Sessions for Breckinridge County was held Monday, August 15, 1803 with William Comstock, Edward Pate and James Jennings presiding. -

Carlyle Connection Sarah Carlyle Herbert’S Elusive Spinet - the Washington Connection by Richard Klingenmaier

The Friends of Carlyle House Newsletter Spring 2017 “It’s a fine beginning.” CarlyleCarlyle Connection Sarah Carlyle Herbert’s Elusive Spinet - The Washington Connection By Richard Klingenmaier “My Sally is just beginning her Spinnet” & Co… for Miss Patsy”, dated October 12, 1761, George John Carlyle, 1766 (1) Washington requested: “1 Very good Spinit (sic) to be made by Mr. Plinius, Harpsichord Maker in South Audley Of the furnishings known or believed to have been in John Street Grosvenor Square.” (2) Although surviving accounts Carlyle’s house in Alexandria, Virginia, none is more do not indicate when that spinet actually arrived at Mount fascinating than Sarah Carlyle Herbert’s elusive spinet. Vernon, it would have been there by 1765 when Research confirms that, indeed, Sarah owned a spinet, that Washington hired John Stadler, a German born “Musick it was present in the Carlyle House both before and after Professor” to provide Mrs. Washington and her two her marriage to William Herbert and probably, that it children singing and music lessons. Patsy was to learn to remained there throughout her long life. play the spinet, and her brother Jacky “the fiddle.” Entries in Washington’s diary show that Stadler regularly visited The story of Mount Vernon for the next six years, clear testimony of Sarah Carlyle the respect shown for his services by the Washington Herbert’s family. (3) As tutor Philip Vickers Fithian of Nomini Hall spinet actually would later write of Stadler, “…his entire good-Nature, begins at Cheerfulness, Simplicity & Skill in Music have fixed him Mount Vernon firm in my esteem.” (4) shortly after George Beginning in 1766, Sarah (“Sally”) Carlyle, eldest daughter Washington of wealthy Alexandria merchant John Carlyle and married childhood friend of Patsy Custis, joined the two Custis Martha children for singing and music lessons at the invitation of Dandridge George Washington. -

1934-04-22 [P

ANALOSTAN ISLAND WAS NOTED RESORT Picnic Ground Was Popular Place for Many Washing- tonians—Oldest Inhabitants Ran Races and Played Leap Frog—Ear- ly Owners, George Mason of Gunston Hall an d Gen. j Mason. John Introduction of the knights to the queen. A feature of the Analostan Island tournaments. Island" Is the one that is near and dear to ington, presenting a beautiful site for a mag- THOSE who are practically newcomers BY JOHM CL.4GETT PROCTOR. the hearts of the natives of the District of nificent city extending its whole length. The TOto Washington this old island might mean Columbia and one they cannot, and will not little, for they could not recall it when it re- western side forms the same regular graduation J J ■ T IS easy to lead a horse to water, but soon forget. tained any of its early beauty of a hundred or to ‘Back River.’ formerly an arm of the Poto- 4 4 1 it is hard to make him drink," is a more years ago as the magnificent estate of I very old expression, and to one who mac River, and affords beautiful sites for the Gen. John Mason, who married Anna Maria I knows his a true one as horses, very houses and workshops of artisans, laborers, etc., Murray, the daughter of Dr. James Murray of ■ well. Indeed, it is often applied to Md. Gen. Mason was the son of required in various manufactories, through the Annapolis. other things besides animals. In other George Mason of Gunston Hall, author of the entire ■words, the thought we would convey is, that length. -

Nomination Form

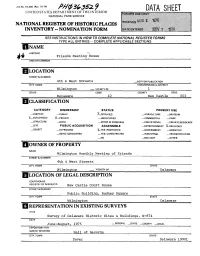

jrm No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) />#$ 36352.9 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR DATA SHEET NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Friends Meeting House AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREETS NUMBER 4th & West Streets -NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Wilmington VICINITY OF 1 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Delaware 10 New Castle 002 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT _PUBLIC ^-OCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X—BUILDING(S) X.-PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE __BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT X_RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _JN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED __YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO .-MILITARY —OTHER: (OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Wilmington Monthly Meeting of Friends STREET & NUMBER 4th & West Streets CITY. TOWN STATE Wilmington VICINITY OF Delaware LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. New Castle Court House STREET & NUMBER Public Building, Rodney Square CITY, TOWN STATE Wilmington Delaware 1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Survey of Delaware Historic Sites & Buildings, N-874 DATE June-August, 1975 —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Hall of Records CITY, TOWN STATE Dover Delaware 19901 DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE ^-EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X_ORIGINALSITE —GOOD —RUINS X-ALTERED —MOVED DATE_ —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Friends Meeting House, majestically situated on Quaker Hill, was built between 1815 and 1817 and has changed little since it was built. What change has occurred has not altered the integrity of the building. -

Domestic Management of Woodlawn Plantation: Eleanor Parke Custis Lewis and Her Slaves

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1993 Domestic Management of Woodlawn Plantation: Eleanor Parke Custis Lewis and Her Slaves Mary Geraghty College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, African History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Geraghty, Mary, "Domestic Management of Woodlawn Plantation: Eleanor Parke Custis Lewis and Her Slaves" (1993). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625788. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-jk5k-gf34 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DOMESTIC MANAGEMENT OF WOODLAWN PLANTATION: ELEANOR PARKE CUSTIS LEWIS AND HER SLAVES A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of American Studies The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Mary Geraghty 1993 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts -Ln 'ln ixi ;y&Ya.4iistnh A uthor Approved, December 1993 irk. a Bar hiara Carson Vanessa Patrick Colonial Williamsburg /? Jafhes Whittenburg / Department of -

Homelifestyle Page 8 Classifieds, Page 10 Opinion, Page 4 V Classifieds

Betsy Garnes, Lake Ridge, visiting the Community Market at the Workhouse Arts Center in Lorton for Community lunch and shopping with gardening friends, ex- amines oils and gems by Market Opens Susan & Staci, of “Gems 4 U.” Garnes is using the outing opportunity to per- form another regular act In Lorton of kindness in memory of News, Page 7 her father. HomeLifeStyle Page 8 Classifieds, Page 10 Classifieds, v Opinion, Page 4 County Board Recognizes ‘2021 Community Champions’ News, Page 3 Requested in home 4-16-21 home in Requested Time sensitive material. material. sensitive Time Attention Postmaster: Postmaster: Attention ECR WSS ECR Fairfax Restores More Customer Postal permit #322 permit Easton, MD Easton, FY 21 Budget Cuts PAID U.S. Postage U.S. News, Page 6 STD PRSRT Photo by Susan Laume/The Connection Photo April 15-21, 2021 online at www.connectionnewspapers.com Bulletin Board Submit civic/community announcements at Connec- tionNewspapers.com/Calen- dar. Photos and artwork wel- come. Deadline is Thursday at noon, at least two weeks before the event. EVERY SATURDAY Community Market Opens. 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. At Workhouse Arts Center in Lorton. Fea- turing over 20 vendors, new and returning. SATURDAY/APRIL 24 Academy Day. 10 a.m. to 12 noon. Sen. Mark Warner is hosting his annual Academy Day. The event will offer a comprehensive overview of the United States service academies and their admis- sion processes. Attendees will have an opportunity to hear from officials from the five federal service acade- mies, as well as representa- tives from the Department of Defense Medical Exam- ination Review Board, the University of Virginia ROTC programs, the Virginia Tech Corps of Cadets, the Virginia Military Institute, and the Virginia Women’s Institute for Leadership at Mary Baldwin University. -

MERION FRIENDS MEETING HOUSE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service______National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 MERION FRIENDS MEETING HOUSE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service_____________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: MERION FRIENDS MEETING HOUSE Other Name/Site Number: 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 615 Montgomery Avenue Not for publication:_ City/Town: Merion Station Vicinity:_ State: PA County: Montgomery Code: 091 Zip Code: 19006 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): X Public-Local: _ District: _ Public-State: _ Site: _ Public-Federal: Structure: _ Object: _ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 1 _ buildings 1 _ sites _ structures _ objects Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 0 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 MERION FRIENDS MEETING HOUSE Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service_____________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Friends Meeting House, Brigflatts

Friends Meeting House, Brigflatts Brigflatts, Sedbergh, LA10 5HN National Grid Reference: SD 64089 91155 Statement of Significance Brigflatts has exceptional heritage significance as the earliest purpose-built meeting house in the north of England, retaining a richly fitted interior and an unspoilt rural setting. The vernacular building is Grade 1 listed, and important as a destination for visitors as well as a meeting house for Quaker worship. Evidential value The meeting house has high evidential value for its fabric which incorporates historic joinery and fittings of several phases, from the early eighteenth century through to the early 1900s, illustrating incremental repair and renewal. The burial ground and ancillary stable and croft buildings also have archaeological potential. Historical value The site is associated with a 1652 visit by George Fox to the area, and to the growth of Quakerism in this remote rural area. The meeting house was built in 1674-75 and fitted out over the following decades, according to Quaker requirements and simple taste. The burial ground has been in continuous use since 1656 and is the burial place of the poet Basil Bunting. The building and place has exceptional historical value. Aesthetic value The form and design of the building is typical of late seventeenth century vernacular architecture in this area, constructed in local materials and expressing Friends’ approach to worship. The attractive setting of the walled garden, paddock and outbuildings adds to its aesthetic significance. The exterior, interior spaces and historic fittings ad furnishings have exceptional aesthetic value. Communal value The meeting house is primarily a place for Quaker worship but is important to visitors to this western part of the Yorkshire Dales.