Re-Creation Through Recreation, Aspen Skiing from 1870 to 1970

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page 5 of the 2020 Antelope, Deer and Elk Regulations

WYOMING GAME AND FISH COMMISSION Antelope, 2020 Deer and Elk Hunting Regulations Don't forget your conservation stamp Hunters and anglers must purchase a conservation stamp to hunt and fish in Wyoming. (See page 6) See page 18 for more information. wgfd.wyo.gov Wyoming Hunting Regulations | 1 CONTENTS Access on Lands Enrolled in the Department’s Walk-in Areas Elk or Hunter Management Areas .................................................... 4 Hunt area map ............................................................................. 46 Access Yes Program .......................................................................... 4 Hunting seasons .......................................................................... 47 Age Restrictions ................................................................................. 4 Characteristics ............................................................................. 47 Antelope Special archery seasons.............................................................. 57 Hunt area map ..............................................................................12 Disabled hunter season extension.............................................. 57 Hunting seasons ...........................................................................13 Elk Special Management Permit ................................................. 57 Characteristics ..............................................................................13 Youth elk hunters........................................................................ -

ANNUAL UPDATE Winter 2019

ANNUAL UPDATE winter 2019 970.925.3721 | aspenhistory.org @historyaspen OUR COLLECTIVE ROOTS ZUPANCIS HOMESTEAD AT HOLDEN/MAROLT MINING & RANCHING MUSEUM At the 2018 annual Holden/Marolt Hoedown, Archive Building, which garnered two prestigious honors in 2018 for Aspen’s city council proclaimed June 12th “Carl its renovation: the City of Aspen’s Historic Preservation Commission’s Bergman Day” in honor of a lifetime AHS annual Elizabeth Paepcke Award, recognizing projects that made an trustee who was instrumental in creating the outstanding contribution to historic preservation in Aspen; and the Holden/Marolt Mining & Ranching Museum. regional Caroline Bancroft History Project Award given annually by More than 300 community members gathered to History Colorado to honor significant contributions to the advancement remember Carl and enjoy a picnic and good-old- of Colorado history. Thanks to a marked increase in archive donations fashioned fun in his beloved place. over the past few years, the Collection surpassed 63,000 items in 2018, with an ever-growing online collection at archiveaspen.org. On that day, at the site of Pitkin County’s largest industrial enterprise in history, it was easy to see why AHS stewards your stories to foster a sense of community and this community supports Aspen Historical Society’s encourage a vested and informed interest in the future of this special work. Like Carl, the community understands that place. It is our privilege to do this work and we thank you for your Significant progress has been made on the renovation and restoration of three historic structures moved places tell the story of the people, the industries, and support. -

ASPEN MOUNTAIN Master Development Plan

ASPEN MOUNTAIN Master Development 2018 PlanDraft This is the final draft of the Aspen Mt Ski Area Master Development Plan submitted to the Forest Service by Aspen Skiing Company 1/8/2018. A publication quality document will be produced with final formatting and technical editing. II. DESIGN CRITERIA Establishing design criteria is an important component in mountain planning. Following is an overview of the basic design criteria upon which the Aspen Mountain MDP is based. A. DESTINATION RESORTS One common characteristic of destination resorts is that they cater to a significant vacation market and thus offer the types of services and amenities vacationers expect. At the same time, some components of the destination resort are designed specifically with the day-use guest in mind. Additionally, the employment, housing, and community services for both full-time and second-home residents created by destination resorts all encourage the development of a vital and balanced community. This interrelationship is helpful to the long-term success of the destination resort. Destination mountain resorts can be broadly defined by the visitation they attract, which is, in most instances, either regional or national/international. Within these categories are resorts that are purpose-built and others that are within, or adjacent to, existing communities. Aspen Mountain and the adjacent City of Aspen is an example of such a resort that exists adjacent to an existing community that is rich in cultural history, and provides a destination guest with a sense of the Mountain West and the mining and ski history of Colorado. This combination of a desirable setting and history supplements the overall experience of a guest visiting Aspen Mountain, which has become a regional, national, and international destination resort. -

C E N Oz Oi C C Oll a Ps E of T H E E Ast Er N Ui Nt a M O U Nt Ai Ns a N D Dr Ai

Research Paper T H E M E D I S S U E: C Revolution 2: Origin and Evolution of the Colorado River Syste m II GEOSPHERE Cenozoic collapse of the eastern Uinta Mountains and drainage evolution of the Uinta Mountains region G E O S P H E R E; v. 1 4, n o. 1 Andres Aslan 1 , Marisa Boraas-Connors 2 , D o u gl a s A. S pri n k el 3 , Tho mas P. Becker 4 , Ranie Lynds 5 , K arl E. K arl str o m 6 , a n d M att H eizl er 7 1 Depart ment of Physical and Environ mental Sciences, Colorado Mesa University, 1100 North Avenue, Grand Junction, Colorado 81501, U S A doi:10.1130/ G E S01523.1 2 Depart ment of Geosciences, Colorado State University, Natural Resources Building, Roo m 322, Fort Collins, Colorado 80523, U S A 3 Utah Geological Survey, 1594 W North Te mple, Salt Lake City, Utah 84114-6100, U S A 1 5 fi g ur e s; 1 t a bl e; 4 s u p pl e m e nt al fil e s 4 Exxon Mobil Exploration Co mpany, 22777 Spring woods Village Park way, Spring, Texas 77389, U S A 5 Wyo ming State Geological Survey, P. O. Box 1347, Lara mie, Wyo ming 82073, U S A 6 Depart ment of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of Ne w Mexico, Redondo Drive NE, Albuquerque, Ne w Mexico 87131, U S A C O R RESP O N DE N CE: aaslan @colorado mesa .edu 7 Ne w Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources, Ne w Mexico Tech, 801 Leroy Place, Socorro, Ne w Mexico 87801, U S A CI T A TI O N: Aslan, A., Boraas- Connors, M., Sprinkel, D. -

Perspectives of the Sport-Oriented Public in Slovenia on Extreme Sports

Rauter, S. and Doupona Topič, M.: PERSPECTIVES OF THE SPORT-ORIENTED ... Kinesiology 43(2011) 1:82-90 PERSPECTIVES OF THE SPORT-ORIENTED PUBLIC IN SLOVENIA ON EXTREME SPORTS Samo Rauter and Mojca Doupona Topič University of Ljubljana, Faculty of Sport, Ljubljana, Slovenia Original scientific paper UDC 796.61(035) (497.4) Abstract: The purpose of the research was to determine the perspectives of the sport-oriented people regarding the participation of a continuously increasing number of athletes in extreme sports. At the forefront, there is the recognition of the reasons why people actively participate in extreme sports. We were also interested in the popularity of individual sports and in people‘s attitudes regarding the dangers and demands of these types of sports. The research was based on a statistical sample of 1,478 sport-oriented people in Slovenia, who completed an online questionnaire. The results showed that people were very familiar with individual extreme sports, especially the ultra-endurance types of sports. The people who participated in the survey stated that the most dangerous types of sports were: extreme skiing, downhill mountain biking and mountaineering, whilst the most demanding were: Ironman, ultracycling, and ultrarunning. The results have shown a wider popularity of extreme sports amongst men and (particularly among the people participating in the survey) those who themselves prefer to do these types of sports the most. Regarding the younger people involved in the survey, they typically preferred the more dangerous sports as well, whilst the older ones liked the demanding sports more. People consider that the key reasons for the extreme athletes to participate in extreme sports were entertainment, relaxation and the attractiveness of these types of sports. -

THE DETERMINANTS of SKI RESORT SUCCESS the Faculty of the Department of Economics and Business

THE DETERMINANTS OF SKI RESORT SUCCESS A THESIS Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Economics and Business The Colorado College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts By Ezekiel Anouna May/2010 THE DETERMINANTS OF SKI RESORT SUCCESS Ezekiel Anouna May, 2010 Economics Abstract As the economy is in a decline, fewer people are willing to pay for luxuries such as vacations. Thus, the ski resort industry is suffering. This thesis reveals an opportunity m the growth of free skiing and a demand for more difficult terrain. In this paper, data is collected from nearly all Colorado ski resorts to form a regression model explaining resort success. Regression analysis is conducted to discover what aspects of a ski resort contribute to success. Primarily, skier visits from the 2008-2009 ski season are_useclas the dependant variable in the regression model to measure resort success. Additionally, hedonic pricing theory is applied to test lift ticket price as a dependant variable. The paper finds that resort size, and possibly terrain park features are related to resort success. The hedonic pricing regression finds that bowl skiing, and lack of crowds, increase consumer willingness to pay for expensive lift tickets. KEYWORDS: (ski resort, terrain park, hedonic pricing) ON MY HONOR, I HAVE NEITHER GIVEN NOR RECEIVED UNAUTHORIZED AID ON THIS THESIS Signature I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Esther Redmount, for her support and consistent efforts to make sure I was on track. I would like to thank my family for supporting me in so many ways throughout my college career. -

International Design Conference in Aspen Records, 1949-2006

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8pg1t6j Online items available Finding aid for the International Design Conference in Aspen records, 1949-2006 Suzanne Noruschat, Natalie Snoyman and Emmabeth Nanol Finding aid for the International 2007.M.7 1 Design Conference in Aspen records, 1949-2006 ... Descriptive Summary Title: International Design Conference in Aspen records Date (inclusive): 1949-2006 Number: 2007.M.7 Creator/Collector: International Design Conference in Aspen Physical Description: 139 Linear Feet(276 boxes, 6 flat file folders. Computer media: 0.33 GB [1,619 files]) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Founded in 1951, the International Design Conference in Aspen (IDCA) emulated the Bauhaus philosophy by promoting a close collaboration between modern art, design, and commerce. For more than 50 years the conference served as a forum for designers to discuss and disseminate current developments in the related fields of graphic arts, industrial design, and architecture. The records of the IDCA include office files and correspondence, printed conference materials, photographs, posters, and audio and video recordings. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English. Biographical/Historical Note The International Design Conference in Aspen (IDCA) was the brainchild of a Chicago businessman, Walter Paepcke, president of the Container Corporation of America. Having discovered through his work that modern design could make business more profitable, Paepcke set up the conference to promote interaction between artists, manufacturers, and businessmen. -

Section Six: Interpretive Sites Top of the Rockies National Scenic & Historic Byway INTERPRETIVE MANAGEMENT PLAN Copper Mountain to Leadville

Top Of The Rockies National Scenic & Historic Byway Section Six: Interpretive Sites 6-27 INTERPRETIVE MANAGEMENT PLAN INTERPRETIVE SITES Climax Mine Interpretive Site Introduction This section contains information on: • The current status of interpretive sites. • The relative value of interpretive sites with respect to interpreting the TOR topics. • The relative priority of implementing the recommendations outlined. (Note: Some highly valuable sites may be designated “Low Priority” because they are in good condition and there are few improvements to make.) • Site-specific topics and recommendations. In the detailed descriptions that follow, each site’s role in the Byway Interpretive Management Plan is reflected through the assignment of an interpretive quality value [(L)ow, (M)edium, (H) igh], an interpretive development priority [(L)ow, (M)edium, (H)igh], and a recommended designation (Gateway, Station, Stop, Site). Interpretive value assesses the importance, uniqueness and quality of a site’s interpretive resources. For example, the Hayden Ranch has high value as a site to interpret ranching while Camp Hale has high value as a site to interpret military history. Interpretive priority refers to the relative ranking of the site on the Byway’s to do list. High priority sites will generally be addressed ahead of low priority sites. Top Of The Rockies National Scenic and Historic Byway INTERPRETIVE MANAGEMENT PLAN 6-1 Byway sites by interpretive priority HIGH MEDIUM LOW • USFS Office: Minturn • Climax Mine/Freemont Pass • Mayflower Gulch -

War Vets Showed Athletic Prowess in Winter Olympics

War Vets Showed Athletic Prowess in Winter Olympics Jan 31, 2014 By Kelly Gibson The Winter Olympics are relatively young, appearing on the sporting scene for the first time in 1924. As early as 1928, though, war veterans participated. Here are a few of the better- known Olympian-vets among them. (Vets of the 10th Mountain Division who skied in the Olympics and biathlon vets are covered in separate articles.) Eddie P.F. Eagan (1897-1967) b. Denver, Colo. Eagan served stateside with the Artillery Corps during WWI, from July 4 to Dec. 28, 1918. However, during WWII, he saw service in the China-Burma-India and European theaters with the Army’s Air Transport Command. He served as chief of special services from May 13, 1942 until Sept. 30, 1944. As the only American to win a gold medal at both the Summer and Winter Olympics, Eagan showed natural athletic talent growing up. He is best known for his success as a boxer, winning titles in middle and heavyweight competitions. In 1919, he won the heavyweight title in the U.S. amateur championships as Yale’s boxing captain. Eagan, attending Oxford as a Rhodes scholar, became the first American amateur boxing champion of Great Britain. In 1920, Eagan participated in the Summer Olympics in Antwerp, where he won a gold medal in the lightweight boxing division. Despite having no experience with a bobsled, Eagan was invited to join the four-man team participating in the 1932 Winter Olympics at Lake Placid, N.Y., along with fellow veteran Billy Fiske. -

Market Feasibility Study for Town of Gypsum, Colorado

. BRANDT HOSPITALITY CONSULTING, INC. Market Feasibility Study for Town of Gypsum, Colorado .......... Proposed Limited-Service Hotel Eagle County Regional Airport, Gypsum, Colorado Prepared by Isabel B. Ackerman, ISHC June 2, 2019 . Isabel B. Ackerman, ISHC BRANDT HOSPITALITY CONSULTING, INC. 8023 Kingsbury Blvd St. Louis, MO 63105 (314) 899-9701 [email protected] June 2, 2019 Mr. Jeremy Rietmann Town Manager Town of Gypsum 50 Lundgren Boulevard Gypsum, CO 81637970 Office: 970-524-1730 Cell: 970-343-9887 [email protected] Dear Mr. Rietmann: I have completed a feasibility study for the proposed limited-service hotel to be located near the Eagle County Regional Airport in Gypsum, Colorado. This study was completed in accordance with our contract letter dated March 13, 2019. My conclusions in this report are based upon facts gathered during the week of March 24, 2019, and changes in the market subsequent to this date have not been included in the report. The accompanying projections are based on estimates and assumptions developed in connection with the market study. However, some assumptions inevitably will not materialize and unanticipated events and circumstances may occur; therefore, actual results achieved during the period covered by the prospective financial analysis will vary from the estimates, and the variations may have a material impact on the proposed hotel. I have not been engaged to evaluate the effectiveness of management; therefore, the projections are based upon competent and effective management. All data and conclusions in this report are subject to the Assumptions and Limiting Conditions contained in the Exhibits of this report. Sincerely, BRANDT HOSPITALITY CONSULTING, INC. -

Camp Hale Story

Camp Hale Story - Wes Carlson Introduction In 1942, the US Army began the construction of a large Army training facility at Pando, Colorado, located in the Sawatch Range at an elevation of 9,250 feet, between Minturn and Leadville, CO, adjacent to US Highway 24. The training facility became known as Camp Hale and eventually housed over 16,000 soldiers. Camp Hale was chosen as it was to become a training facility for mountain combat troops (later known as the 10th Mountain Division) for the US Army in WWII, and the area was in the mountains similar to what the soldiers might experience in the Alps of Europe. The training facility was constructed on some private land acquired by the US Government, but some of the facilities were on US Forest Service land. Extensive cooperation was required by the US Forest Service throughout the construction and operation of the camp and adjacent facilities. The camp occupied over 5,000 acres and was a city in itself. The Camp Site is located in what is now the White River NF. In 2012, at the US Forest Service National Retiree’s Reunion, a tour of the Camp Hale area was arranged. When the group who had signed up for the tour arrived at the office location where the tour was to start, it was announced that we would not be able to go to the Camp Hale site due to logistical issues with the transportation. One retiree, who had signed up for the tour, was very unhappy, and announced that if we couldn’t go to Camp Hale he would like to return to the hotel in Vail. -

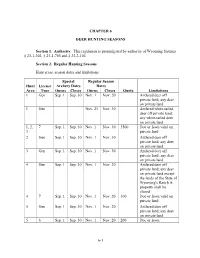

Deer Season Subject to the Species Limitation of Their License in the Hunt Area(S) Where Their License Is Valid As Specified in Section 2 of This Chapter

CHAPTER 6 DEER HUNTING SEASONS Section 1. Authority. This regulation is promulgated by authority of Wyoming Statutes § 23-1-302, § 23-1-703 and § 23-2-104. Section 2. Regular Hunting Seasons. Hunt areas, season dates and limitations. Special Regular Season Hunt License Archery Dates Dates Area Type Opens Closes Opens Closes Quota Limitations 1 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land 1 Gen Nov. 21 Nov. 30 Antlered white-tailed deer off private land; any white-tailed deer on private land 1, 2, 7 Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 30 3500 Doe or fawn valid on 3 private land 2 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 30 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land 3 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 30 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land 4 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land except the lands of the State of Wyoming's Ranch A property shall be closed 4 7 Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 300 Doe or fawn valid on private land 5 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land 5 6 Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 200 Doe or fawn 6-1 6 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land 7 Gen Sep.