127179869.23.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Act of Sederunt (Simple Procedure) 2016 SSI 2016/200

Act of Sederunt (Simple Procedure) 2016 SSI 2016/200 1. Citation and commencement, etc 2. The Simple Procedure Rules 3. Interpretation of the Simple Procedure Rules 4. Warrants 5. Arrestment to found jurisdiction Citation and commencement, etc 1. (1) This Act of Sederunt may be cited as the Act of Sederunt (Simple Procedure) 2016. (2) It comes into force on 28th November 2016. (3) A certified copy is to be inserted in the Books of Sederunt. The Simple Procedure Rules 2. (1) Schedule 1 contains rules for simple procedure cases and may be cited as the Simple Procedure Rules. (2) A form referred to in the Simple Procedure Rules means— (a) the form with that name in Schedule 2, or (b) an electronic version of the form with that name in Schedule 2, adapted for use by the Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service with the portal on its website. (3) Where the Simple Procedure Rules require a form to be used, that form may be varied where the circumstances require it. Interpretation of the Simple Procedure Rules 3. (1) In the Simple Procedure Rules— “a case where the expenses of a claim are capped” means a simple procedure case— (a) to which an order made under section 81(1) of the Courts Reform (Scotland) Act 2014a applies; or (b) in which the sheriff has made a direction under section 81(7) of that Act; [omitted in consequentials] “a decision which absolves the respondent” means a decree of absolvitor; “a decision which orders the respondent to deliver something to the claimant” means a decree for delivery or for recovery of possession; “a decision -

Advocate General Commissioned an Expert Group, Chaired by Sir David Edward, to Examine the Position 1

Scotland Act 2012 – commencement of provisions relating to Supreme Court appeals Following the coming into force of the Scotland Act 1998, the UK Supreme Court and its predecessors were given a role in determining “devolution issues” arising in court proceedings. Devolution issues under the 1998 Act include questions whether an Act of the Scottish Parliament is within its legislative competence, and whether the purported or proposed exercise of a function by a member of the Scottish Executive would be incompatible with any of the rights under the European Convention on Human Rights or with the law of the European Union. This included the exercise of functions by the Lord Advocate as prosecutor, with the effect that the Supreme Court was given a role defined in statute in relation to Scottish criminal cases for the first time. The Scotland Act 2012 makes substantial amendments to this aspect of the 1998 Act and creates a new scheme of appeals in relation to “compatibility issues”. “Compatibility issues” are questions arising in criminal proceedings about EU law and ECHR issues, or challenges to Acts of the Scottish Parliament on ECHR or EU law compatibility grounds. These issues would currently be dealt with as devolution issues under the regime created by the 1998 Act. Under the 2012 Act provisions, the remit of the UK Supreme Court is to determine the compatibility issue and then remit to the High Court for such further action as that court should see fit. The 2012 Act also imposes time limits in appeals to the Supreme Court in the new system and introduces the same time limit in appeals to the Supreme Court in relation to devolution issues arising in criminal proceedings. -

Act of Adjournal (Criminal Procedure Rules 1996 Amendment) (Approval of Sentencing Guidelines) 2018

Certified copy from legislation.gov.uk Publishing SCOTTISH STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2018 No. 229 HIGH COURT OF JUSTICIARY Act of Adjournal (Criminal Procedure Rules 1996 Amendment) (Approval of Sentencing Guidelines) 2018 Made - - - - 12th July 2018 Laid before the Scottish Parliament 16th July 2018 Coming into force - - 4th September 2018 The High Court of Justiciary makes this Act of Adjournal under the powers conferred by section 305 of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995( a) and all other powers enabling it to do so. Citation and commencement, etc. 1. —(1) This Act of Adjournal may be cited as the Act of Adjournal (Criminal Procedure Rules 1996 Amendment) (Approval of Sentencing Guidelines) 2018. (2) It comes into force on 4th September 2018. (3) A certified copy is to be inserted in the Books of Adjournal. Amendment of the Criminal Procedure Rules 1996 2. —(1) The Criminal Procedure Rules 1996( b) are amended in accordance with this paragraph. (2) After Chapter 67 (European Investigation Orders)(c) insert— “CHAPTER 68 APPROVAL OF SENTENCING GUIDELINES Interpretation of this Chapter 68.1. In this Chapter “the Council” means the Scottish Sentencing Council within the meaning of section 1 of the Criminal Justice and Licensing (Scotland) Act 2010( d). (a) 1995 c.46. Section 305 was amended by section 111(1) of the Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 2016 (asp 1) and by article 2 of S.S.I. 2015/338, and was extended by section 386(3)(a) of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (c.29), section 36A(4) of the Serious Crime Act 2007 (c.27), and section 32(5) of the Psychoactive Substances Act 2016 (c.2). -

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part Two ISBN 0 902198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART II K-Z C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography. -

Explanatory Notes

This document relates to the Criminal Proceedings etc. (Reform) (Scotland) Bill as amended at Stage 2 (SP Bill 55A) CRIMINAL PROCEEDINGS ETC. (REFORM) (SCOTLAND) BILL —————————— SUPPLEMENTARY DELEGATED POWERS MEMORANDUM Purpose 1. This supplementary Memorandum has been prepared by the Scottish Executive to accompany the Criminal Proceedings etc. (Reform) (Scotland) Bill following Stage 2 consideration of that Bill, which concluded on 22 November 2006. It has been produced in accordance with Rule 9.7.10 of the Parliament’s Standing Orders to assist consideration by the Subordinate Legislation Committee in accordance with Rule 9.7.9. 2. It explains changes to the powers to make subordinate legislation under the Criminal Proceedings etc. (Reform) (Scotland) Bill made as a consequence of amendments at Stage 2 where these add new powers to make subordinate legislation or substantially alter powers which were already in the Bill. It describes the persons upon whom these powers are conferred, the form in which the powers are to be exercised, the Parliamentary procedure to which the powers are to be subject and, in respect of new powers, why it is considered necessary to delegate the powers. It does not form part of the Bill and has not been endorsed by the Parliament. This supplementary Memorandum should be read in conjunction with the original Memorandum. 3. References to “the 1995 Act” in this Memorandum relate to the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995 (c.46). FURTHER AND AMENDED DELEGATED POWERS Section 7A – Power to make provision in relation to various forms of electronic documentation, storage and communication Section 7A(2) of the Bill Power conferred on: Scottish Ministers Power exercisable by: Order made by statutory instrument Parliamentary procedure: Negative resolution of the Scottish Parliament 4. -

Justice of the Peace Court: Act of Adjournal: Criminal Procedure Rules: Scotland

436 THE LONDON GAZETTE TUESDAY 14 JUNE 2011 SUPPLEMENT No. 3 Justice of the Peace Court: Act of Adjournal: Criminal procedure rules: Scotland ................311, 312, 318 Justice: Acts: Explanatory notes: Northern Ireland ......................................410 Justice: Acts: Northern Ireland ................................................410 Justices of the Peace: Local justice areas ...........................................390 Justices’ clerks: Magistrates’ courts: Procedure: England & Wales .............................256 K Kennet & Avon Canal: Reclassification: British Waterways Board .............................232 Kilkeel: Waiting restrictions: Northern Ireland ........................................334 Knives: Children & young persons: Sales & hire: Scotland .................................105 L Land & buildings: Value added tax.............................................31,96 Land acquisition: Time extensions: Edinburgh Tram (Line One) Act 2006: Scotland ....................113 Land acquisition: Time extensions: Edinburgh Tram (Line Two) Act 2006: Scotland....................114 Land drainage: Ainsty (2008) Internal Drainage Board....................................253 Land drainage: Internal drainage districts: Amalgamation ..................................254 Land drainage: Isle of Axholme & North Nottinghamshire Water Level Management Board ................254 Land drainage: Scotter Drainage Authority: Abolition.....................................72 Land drainage: Scotter Internal Drainage District: Abolition .................................72 -

Sea Fisheries: Creels: Marking: Scotland

246-277 JULY, 312-330 AUG., 368-397 SEPT., 438-463 OCT. Sea fisheries: Creels: Marking: Scotland .................................................210 Sea fisheries: Edible crabs: Conservation: Northern Ireland ........................................274 Sea fisheries: Edible crabs: Undersized: Northern Ireland .........................................274 Sea fisheries: Licences & notices: Revocation: Northern Ireland ......................................46 Sea fisheries: Licensing: Revocation: Northern Ireland ...........................................46 Sea fishing see also Sea fisheriesd Seafarers: Collective redundancies, information & consultation & insolvency: Northern Ireland .......................16 Secure training centres: Coronavirus: England & Wales..........................................262 Seed, plant & propagating material: Marketing: Wales........................................315, 319 Seeds & plant material: Scotland ..................................................209, 211 Seeds, plant & propagating material: Marketing: England ......................................257, 262 Seeds: Fees: Scotland ..........................................................164 Seeds: Fruit plant & propagating material: Marketing: England ...................................112, 114 Seeds: Fruit plant & propagating material: Marketing: Scotland ....................................42, 44 Seeds: Fruit plant & propagating material: Marketing: Wales ......................................71, 74 Seeds: Pesticides, genetically modified organisms -

Public Records (Scotland) Act 1937

DISCLAIMER: As Member States provide national legislations, hyperlinks and explanatory notes (if any), UNESCO does not guarantee their accuracy, nor their up-dating on this web site, and is not liable for any incorrect information. COPYRIGHT: All rights reserved.This information may be used only for research, educational, legal and non- commercial purposes, with acknowledgement of UNESCO Cultural Heritage Laws Database as the source (© UNESCO). Public Records – Scotland- Act, 1937 1937 (1 Edw. 8 & 1 Geo. 6.) CHAPTER 43. [6th July 1937.] An Act to make better provision for the preservation, care and custody of the Public Records of Scotland, and for the discharge of the duties of Principal Extractor of the Court of Session. BE it enacted by the King's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:— PART I COURT RECORDS; 1. High Court and Court of Session records. (1) The records of the High Court of Justiciary and of the Court of Session shall be transmitted to the Keeper of the Registers and Records of Scotland (hereinafter referred to as the Keeper) at such times, and subject to such conditions, as may respectively be prescribed by Act of Adjournal or Act of Sederunt. (2) An Act of Adjournal or an Act of Sederunt under the foregoing subsection may fix different times and conditions of transmission for different classes of records and may make provision for re-transmission of records to the Court when such re-transmission is necessary for the purpose of any proceedings before the Court, and for the return to the Keeper of records so re-transmitted as soon as may be after they have ceased to be required for such purpose. -

![(Scotland) Bill [AS INTRODUCED]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5230/scotland-bill-as-introduced-1025230.webp)

(Scotland) Bill [AS INTRODUCED]

Management of Offenders (Scotland) Bill [AS INTRODUCED] CONTENTS Section PART 1 ELECTRONIC MONITORING ETC. Monitoring in criminal proceedings 1 Requirement when disposing of case 2 Particular rules regarding disposals 3 List of the relevant disposals 4 More about the list of disposals Monitoring on release on parole 5 Requirement with licence conditions 6 Particular rules regarding conditions 7 List of the relevant conditions Devices, use and information 8 Approved devices to be prescribed 9 Use of devices and information Arrangements and designation 10 Arrangements for monitoring system 11 Designation of person to do monitoring Obligations and compliance 12 Standard obligations put on offenders 13 Deemed breach of disposal or conditions 14 Documentary evidence at breach hearings SSI procedure and schedule 15 Procedure for making regulations 16 Additional and consequential provisions PART 2 DISCLOSURE OF CONVICTIONS Rules relating to disclosure 17 Effect of expiry of disclosure periods 18 Sentences excluded from becoming spent SP Bill 27 Session 5 (2019) ii Management of Offenders (Scotland) Bill 19 Disclosure periods for particular sentences 20 Table A – disclosure periods: ordinary cases 21 Table B – disclosure periods: service sentences 22 Disclosure period: caution for good behaviour 23 Disclosure period: particular court orders 24 Disclosure period: adjournment or deferral 25 Disclosure period: mental health orders 26 Disclosure period: compulsion orders 27 Disclosure period: juvenile offenders 28 Disclosure period: service discipline -

Thomas Graham. I. Contributions to Thermodynamics, Chemistry, and the Occlusion of Gases

para quitarle el polvo Educ. quím., 24(3), 316-325, 2013. © Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, ISSN 0187-893-X Publicado en línea el 4 de junio de 2013, ISSNE 1870-8404 Thomas Graham. I. Contributions to thermodynamics, chemistry, and the occlusion of gases Jaime Wisniak* ABSTRACT Thomas Graham (1805-1869) is known as the founder of colloidal chemistry and for his fun- damental research on the nature of phosphoric acid and phosphates, diffusion of gases, liq- uids, and solutions, adsorption of gases by metals, dialysis, osmosis, mass transfer through membranes, and the constitution of matter. KEYWORDS: absorption of gases, gas liquefaction, occlusion of gases, phosphoric acid, polybasicity Resumen fy his father’s wishes that he should follow a long family tra- A Thomas Graham (1805-1869) se le conoce como el funda- dition and became a Minister in the Church of Scotland. In dor de la química coloidal y por sus investigaciones fun- September 1825 Graham read his first chemical paper on the damentales en las áreas de la naturaleza del ácido fosfórico absorption of gases by liquids (Graham, 1826) to the Glas- y los fosfatos, difusión de gases, líquidos y soluciones, ad- gow University Chemical Society and in 1826 he was award- sorción de gases por los metales, diálisis, osmosis, fenóme- ed the degree of MA. At this time, the profound difference of nos de transferencia a través de membranas, y constitución opinion with his father insistence that Thomas should fol- de la materia. low a religious career, led to a rupture of relations and the suspension of the paternal economical support. -

A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

European and non-European medical practices: India and the West Indies, 1750-1900. CURRIE, Simon. Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20652/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20652/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. CollegiateLearning Centre Collegiate Crescent"Campus Sheffield S102QP 101 807 123 7 REFERENCE ProQuest Number: 10701299 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10701299 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 European and Non-European Medical Practices: India and the West Indies, 1750-1900 Simon Currie A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2005 ABSTRACT This thesis compares the interaction between British doctors and Indian medical practitioners with that between such doctors and African-Caribbean practitioners during the period 1750 to 1900. -

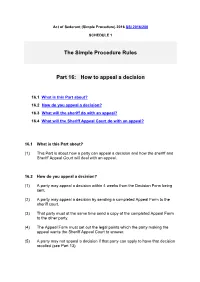

Part 16: How to Appeal a Decision

Act of Sederunt (Simple Procedure) 2016 SSI 2016/200 SCHEDULE 1 The Simple Procedure Rules Part 16: How to appeal a decision 16.1 What is this Part about? 16.2 How do you appeal a decision? 16.3 What will the sheriff do with an appeal? 16.4 What will the Sheriff Appeal Court do with an appeal? 16.1 What is this Part about? (1) This Part is about how a party can appeal a decision and how the sheriff and Sheriff Appeal Court will deal with an appeal. 16.2 How do you appeal a decision? (1) A party may appeal a decision within 4 weeks from the Decision Form being sent. (2) A party may appeal a decision by sending a completed Appeal Form to the sheriff court. (3) That party must at the same time send a copy of the completed Appeal Form to the other party. (4) The Appeal Form must set out the legal points which the party making the appeal wants the Sheriff Appeal Court to answer. (5) A party may not appeal a decision if that party can apply to have that decision recalled (see Part 13). 16.3 What will the sheriff do with an appeal? (1) The sheriff must prepare a draft Appeal Report within 4 weeks of the court receiving an Appeal Form. (2) The draft Appeal Report must set out the factual and legal basis for the decision which the sheriff came to. (3) The draft Appeal Report must set out legal questions for the Sheriff Appeal Court to answer.