Municipal Districts: a Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020-Polling-Scheme

SOUTH DUBLIN COUNTY COUNCIL COMHAIRLE CONTAE ÁTHA CLIATH THEAS POLLING SCHEME 2020 SCHEME OF POLLING DISTRICTS AND POLLING PLACES Local Electoral Area Boundary Committee No. 2 Report 2018 1 Scheme of Polling Districts and Polling Places 2020 This polling scheme applies to Dail, Presidential,European Parliament, Local Elections and Referendums. The scheme is made pursuant to Section 18, of the Electoral Act, 1991 as amended by Section 2 of the Electoral (Amendment) Act, 1996, and Sections 12 and 13 of the Electoral (Amendment) Act, 2001 and in accordance with the Electoral ( Polling Schemes) Regulations, 1005. (S.I. No. 108 of 2005 ). These Regulations were made by the Minister of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government under Section 28 (l) of the Electoral Act, 1992. Constituencies are as contained and described in the Constituency Commission Report 2017. Local Electoral Areas are as contained and described in the Local Electoral Area Boundary Committee No. 2 Report 2018 Electoral Divisions are as contained and described in the County Borough of Dublin (Wards) Regulations, 1986 ( S.I.No. 12 of 1986 ), as amended by the County Borough of Dublin (Wards) (Amendment) Regulations, 1994 ( S.I.No. 109 of 1994) and as amended by the County Borough of Dublin (Wards) (Amendment) Regulations 1997 ( S.I.No. 43 of 1997 ). Effective from 15th February 2020 2 Constituencies are as contained and described in the Constituency Commission Report 2017. 3 INDEX DÁIL CONSTITUENCY AREA: LOCAL ELECTORAL AREA: Dublin Mid-West Clondalkin Dublin Mid-West Lucan Dublin Mid- West Palmerstown- Fonthill Dublin South Central Rathfarnham -Templeogue Dublin South West Rathfarnham – Templeogue Dublin South West Firhouse – Bohernabreena Dublin South West Tallaght- Central Dublin South West Tallaght- South 4 POLLING SCHEME 2020 DÁIL CONSTITUENCY AREA: DUBLIN-MID WEST LOCAL ELECTORAL AREA: CLONDALKIN POLLING Book AREA CONTAINED IN POLLING DISTRICT POLLING DISTRICT / ELECTORAL DIVISIONS OF: PLACE Bawnogue 1 FR Clondalkin-Dunawley E.D. -

Constitution of the Irish Free State (Saorstát Eireann) Act, 1922

Constitution of the Irish Free State (Saorstát Eireann) Act, 1922 CONSTITUTION OF THE IRISH FREE STATE (SAORSTÁT EIREANN) ACT, 1922. AN ACT TO ENACT A CONSTITUTION FOR THE IRISH FREE STATE (SAORSTÁT EIREANN) AND FOR IMPLEMENTING THE TREATY BETWEEN GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND SIGNED AT LONDON ON THE 6TH DAY OF DECEMBER, 1921. DÁIL EIREANN sitting as a Constituent Assembly in this Provisional Parliament, acknowledging that all lawful authority comes from God to the people and in the confidence that the National life and unity of Ireland shall thus be restored, hereby proclaims the establishment of The Irish Free State (otherwise called Saorstát Eireann) and in the exercise of undoubted right, decrees and enacts as follows:— 1. The Constitution set forth in the First Schedule hereto annexed shall be the Constitution of The Irish Free State (Saorstát Eireann). 2. The said Constitution shall be construed with reference to the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty between Great Britain and Ireland set forth in the Second Schedule hereto annexed (hereinafter referred to as “the Scheduled Treaty”) which are hereby given the force of law, and if any provision of the said Constitution or of any amendment thereof or of any law made thereunder is in any respect repugnant to any of the provisions of the Scheduled Treaty, it shall, to the extent only of such repugnancy, be absolutely void and inoperative and the Parliament and the Executive Council of the Irish Free State (Saorstát Eireann) shall respectively pass such further legislation and do all such other things as may be necessary to implement the Scheduled Treaty. -

Remarks by H.E. Luo Linquan, Chinese Ambassador to Ireland, At

Remarks by H.E. Luo Linquan, During my “short but intense” two and a half years’ tenure, I Chinese Ambassador to Ireland, have been fortunate enough to witness and participate in two great events: Mr. Xi Jinping’s visit to Ireland in February 2012, at his Farewell Reception and the Taoiseach’s visit to China one month later. These (Dublin, 20 February 2014) two visits have elevated the friendly ties between China and Ireland to a historically new high point, and have ushered in a Ceann Comhairle, new era for us to build a Strategic Partnership for Mutually Minister Simon Coveney, Beneficial Cooperation. Minister Jimmy Deenihan, Minister Frances Fitzgerald, President Xi was so impressed and pleased with his successful Minister James Reilly, visit to Ireland that he now keeps in his office, next to pictures Dean of the diplomatic corps, Dear Colleagues, of his family, a photograph of him kicking Gaelic football at Distinguished Guests, Croak Park, and this picture is one of the only six photos in his Ladies and Gentlemen: office. Good afternoon! Last Thursday when I paid a farewell courtesy call to the Taoiseach, Mr. Kenny reaffirmed his personal commitment to Thank you all so much for attending my farewell reception. I Ireland’s Strategic Partnership with China. arrived in Dublin on August 26th, 2011, and I will be concluding my tenure as the 11th Ambassador of the People’s The important consensus reached between our top national Republic of China to Ireland at the end of this month. leaders has not only indicated and illuminated the direction of China-Ireland relations, but it has also created fresh, strong At this moment, my heart is filled with gratitude, reluctance impetus for the development of shared interests. -

Global Ireland Progress Report Year 1 June 2018 — June 2019

Global Ireland Progress Report Year 1 June 2018 — June 2019 Global Ireland Progress Report Year 1 (June 2018-June 2019) Prepared by the Department of the Taoiseach July 2019 www.gov.ie/globalireland 2 Global Ireland Progress Report, Year 1 Table of Contents Foreword 4 Progress Overview 5 Investing in Ireland’s global footprint 9 Expanding and deepening Ireland’s global footprint 12 Connecting with the wider world 26 International Development, Peace and Security 34 3 Global Ireland Progress Report, Year 1 Foreword Global Ireland is an expression of Ireland’s ambition about what we want to accomplish on the international stage, and how we believe we can contribute in a positive way to the world we live in. Within the EU, we are working to broaden and deepen our strategic and economic partnerships with other regions and partner countries, across Africa, Asia-Pacific, the Americas and the Middle East, as well as in our near European neighbourhood. We believe in the multilateral system, with the United Nations and the World Trade Organisation at its core, and we see it as the best way to protect our national interests and progress our international objectives. Last June, we launched Global Ireland, a strategic initiative to double Ireland’s global footprint and impact by 2025. When I first announced this initiative, I recalled the words of Taoiseach John A. Costello in 1948, when he expressed a hope that Ireland could wield an influence in the world ‘far in excess of what our mere physical size and the smallness of our population might warrant’. -

Northern Ireland: Managing R COVID-19 Across Open Borders ESSAY SPECIAL ISSUE Katy Hayward *

Borders in Globalization Review Volume 2, Issue 1 (Fall/Winter 2020): 58-61 https://doi.org/10.18357/bigr21202019887 Northern Ireland: Managing _ R COVID-19 Across Open Borders ESSAY SPECIAL ISSUE Katy Hayward * The early response to the coronavirus pandemic in Northern Ireland revealed three things. First, although part of the United Kingdom, Northern Ireland is integrally connected in very practical ways to the Republic of Ireland. Policies and practices regarding COVID-19 on the southern side of the Irish land border had a direct impact on those being formu- lated for the North. Secondly, as well as differences in scientific advice and political preferences in the bordering jurisdictions, a coherent policy response was delayed by leaders’ failures to communicate in a timely manner with counterparts on the other side of the border. And, thirdly, different policies on either side of an open border can fuel profound uncertainty in a borderland region; but this can give rise to community-level action that fills the gaps in ways that can actually better respond to the complexity of the situation. This essay draws on the author’s close observation of events as they happened, including news coverage, press conferences and public statements from the three governments concerned over the period of March-October 2020. The Land and Sea Borders Before COVID-19 Northern Ireland is a small region on the north-eastern UK Government in Westminster. Although Northern part of the island of Ireland that is part of the United Ireland is part of the UK’s National Health Service, Kingdom. -

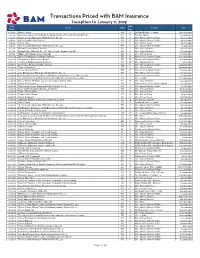

BAM Priced Transactions

Transactions Priced with BAM Insurance Inception to January 11, 2019 Sale Sale Issuer State Sector Par Date Type 1/10/19 Sharp County AR N Dedicated Sales - County $10,340,000 1/9/19 Successor Agency of the Redevelopment Agency of the City of Lake Elsinore CA N Tax Increment $9,260,000 1/9/19 Harris County Municipal Utility District No. 64 TX C GO - Special District Utility $1,535,000 1/8/19 Rolling Creek Utility District TX C GO - Special District Utility $6,595,000 1/8/19 City of Alton TX N GO - City or Town $3,715,000 1/8/19 Harris County Municipal Utility District No. 529 TX C GO - Special District Utility $1,550,000 1/7/19 Warren County School District PA C GO - School District $9,945,000 1/7/19 Unified School District No. 477, Gray County, Kansas (Ingalls) KS C GO - School District $1,500,000 1/7/19 Village of Fontana-on-Geneva Lake WI C GO - City or Town $7,705,000 12/21/18 Upper Trinity Regional Water District TX N Water and/or Sewer Utility $28,390,000 12/21/18 Leavenworth Waterworks Board KS PP Water and/or Sewer Utility $6,900,000 12/21/18 Frankfort Redevelopment Authority IN PP GO - Special District $515,500 12/20/18 New Caney Municipal Utility District TX C GO - Special District Utility $12,100,000 12/19/18 Town of Stratford CT C GO - City or Town $70,000,000 12/18/18 City of Charles Town WV N Water and/or Sewer Utility $3,065,000 12/13/18 Fort Bend County Municipal Utility District No. -

The Executive's International Relations and Comparisons with Scotland & Wales

Research and Information Service Briefing Paper Paper 04/21 27/11/2020 NIAR 261-20 The Executive’s International Relations and comparisons with Scotland & Wales Stephen Orme Providing research and information services to the Northern Ireland Assembly 1 NIAR 261-20 Briefing Paper Key Points This briefing provides information on the Northern Ireland Executive’s international relations strategy and places this in a comparative context, in which the approaches of the Scottish and Welsh governments are also detailed. The following key points specify areas which may be of particular interest to the Committee for the Executive Office. The Executive’s most recent international relations strategy was published in 2014. Since then there have been significant changes in the global environment and Northern Ireland’s position in it, including Brexit and its consequences. Northern Ireland will have a unique and ongoing close relationship with the EU, due in part to the requirements of the Ireland/Northern Ireland Protocol. The Scottish and Welsh parliaments have launched and/or completed inquiries into their countries’ international relations in recent years. The Scottish and Welsh governments have also taken recent steps to update and refresh their approach to international relations. There is substantial variation in the functions of the international offices of the devolved administrations. NI Executive and Scottish Government offices pursue a broad range of diplomatic, economic, cultural, educational and specific policy priorities, with substantial variation between offices. Welsh Government offices, meanwhile, appear primarily focused on trade missions. It is therefore difficult to compare the international offices of the three administrations on a “like for like” basis. -

To the Lord Mayor and Report No. 12/2019 Members of Dublin City Council Report of Assistant Chief Executive

To the Lord Mayor and Report No. 12/2019 Members of Dublin City Council Report of Assistant Chief Executive _________________________________________________________________________ Revised Area Committee Structures – Post Local Elections 2019 _________________________________________________________________________ The new boundary provisions for the next City Council elections will be implemented from June 2019. The number of Local Electoral Areas (LEAs) in Dublin City will increase from 9 at present to 11 (Six on the north side and five on the south side). There will be no change in the number of elected members which will remain at 63. The local electoral areas will be smaller with a maximum of 7 elected members in each. The biggest changes in boundaries refer to the amalgamation of Rathmines with Crumlin/Kimmage and the creation of a new area covering Whitehall/Artane, however no existing area is left fully unchanged. These changes have implications for our existing area committee boundaries that have been in place for the last 10 years. They will also have implications for our existing area management structures, but this does give us a welcome opportunity to review, re-define and enhance those management structures. This report concentrates on the area committee boundaries and once these are agreed then we can focus on the staffing arrangements to support those structures and implement same before the elections are held in May 2019. The adoption of an area committee structure is a reserved function. I am setting out below details of the current structure and arrangements and I am also setting out a number of different options that could be put in place after the Local Elections in May 2019. -

County of South Dublin Local Electoral Areas Order 2009

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS S.I. No. 47 of 2009 ———————— COUNTY OF SOUTH DUBLIN LOCAL ELECTORAL AREAS ORDER 2009 (Prn. A9/0194) 2 [47] S.I. No. 47 of 2009 COUNTY OF SOUTH DUBLIN LOCAL ELECTORAL AREAS ORDER 2009 The Minister for the Environment, Heritage and Local Government, in exer- cise of the powers conferred on him by sections 3 and 24 of the Local Govern- ment Act 1994 (No. 8 of 1994), hereby orders as follows: 1. This order may be cited as the County of South Dublin Local Electoral Areas Order 2009. 2. (1) The County of South Dublin shall be divided into the local electoral areas which are named in the first column of the Schedule to this Order. (2) Each such local electoral area shall consist of the area described in the second column of the Schedule to this Order opposite the name of such local electoral area. (3) The number of members of South Dublin County Council to be elected for each such local electoral area shall be the number set out in the third column of the Schedule to this Order opposite the name of that local electoral area. 3. Every reference in the Schedule to this Order to an electoral division shall be construed as referring to such electoral division as existing at the date of this Order. 4. (1) A reference in the Schedule to this Order to a line drawn along any road shall be construed as a reference to an imaginary line drawn along the centre of such road. (2) A reference in the Schedule to this Order to the point at which any road intersects or joins any other road shall be construed as a reference to the point at which an imaginary line drawn along the centre of one would be intersected or joined by an imaginary line drawn along the centre of the other. -

2018 Municipal Affairs Population List | Cities 1

2018 Municipal Affairs Population List | Cities 1 Alberta Municipal Affairs, Government of Alberta November 2018 2018 Municipal Affairs Population List ISBN 978-1-4601-4254-7 ISSN 2368-7320 Data for this publication are from the 2016 federal census of Canada, or from the 2018 municipal census conducted by municipalities. For more detailed data on the census conducted by Alberta municipalities, please contact the municipalities directly. © Government of Alberta 2018 The publication is released under the Open Government Licence. This publication and previous editions of the Municipal Affairs Population List are available in pdf and excel version at http://www.municipalaffairs.alberta.ca/municipal-population-list and https://open.alberta.ca/publications/2368-7320. Strategic Policy and Planning Branch Alberta Municipal Affairs 17th Floor, Commerce Place 10155 - 102 Street Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4L4 Phone: (780) 427-2225 Fax: (780) 420-1016 E-mail: [email protected] Fax: 780-420-1016 Toll-free in Alberta, first dial 310-0000. Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 4 2018 Municipal Census Participation List .................................................................................... 5 Municipal Population Summary ................................................................................................... 5 2018 Municipal Affairs Population List ....................................................................................... -

Government of Ireland Act, 1920. 10 & 11 Geo

?714 Government of Ireland Act, 1920. 10 & 11 GEo. 5. CH. 67.] To be returned to HMSO PC12C1 for Controller's Library Run No. E.1. Bin No. 0-5 01 Box No. Year. RANGEMENT OF SECTIONS. A.D. 1920. IUD - ESTABLISHMENT OF PARLIAMENTS FOR SOUTHERN IRELAND. AND NORTHERN IRELAND AND A COUNCIL OF IRELAND. Section. 1. Establishment of Parliaments of Southern and Northern Ireland. 2. Constitution of Council of Ireland. POWER TO ESTABLISH A PARLIAMENT FOR THE WHOLE OF IRELAND. Power to establish a Parliament for the whole of Ireland. LEGISLATIVE POWERS. 4. ,,.Legislative powers of Irish Parliaments. 5. Prohibition of -laws interfering with religious equality, taking property without compensation, &c. '6. Conflict of laws. 7. Powers of Council of Ireland to make orders respecting private Bill legislation for whole of Ireland. EXECUTIVE AUTHORITY. S. Executive powers. '.9. Reserved matters. 10. Powers of Council of Ireland. PROVISIONS AS TO PARLIAMENTS OF SOUTHERN AND NORTHERN IRELAND. 11. Summoning, &c., of Parliaments. 12. Royal assent to Bills. 13. Constitution of Senates. 14. Constitution of the Parliaments. 15. Application of election laws. a i [CH. 67.1 Government of Ireland Act, 1920, [10 & 11 CEo. A.D. 1920. Section. 16. Money Bills. 17. Disagreement between two Houses of Parliament of Southern Ireland or Parliament of Northern Ireland. LS. Privileges, qualifications, &c. of members of the Parlia- ments. IRISH REPRESENTATION IN THE HOUSE OF COMMONS. ,19. Representation of Ireland in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom. FINANCIAL PROVISIONS. 20. Establishment of Southern and Northern Irish Exchequers. 21. Powers of taxation. 22. -

City Administrator Full PPT 2-25-19

Your Logo Here BETTER TOGETHER PROPOSAL IMPACT ON TOWN AND COUNTRY Revised March 14, 2019 1 Your Logo Better Together Proposal Here . Better Together Proposal Issued Publicly at Press Conference on January 25, 2019. Revised petition filed February 11, 2019. Calls for Statewide Vote on Constitutional Amendment in November 2020 o Creates a new class of city - “A Metropolitan City” o Unify St Louis City & St Louis County as a Metropolitan City o Cities in St Louis County to become “Municipal Divisions” of the Metropolitan City . Effective Date is January 1, 2021 o Transition Period of Two Years to Full Implementation in January 2023 o First election for Metropolitan City Council in November 2022; take office January 2023 o First elections for Metro Mayor, Prosecutor and Assessor November 2024; take office January 2025 2 METROPOLITAN “METRO” Your Logo CITY OF ST LOUIS Here . Combine St Louis City and County into Single Government, Population 1.3 million . All existing cities (including St Louis City and Town & Country) to become Municipal Districts . Partisan Elections for all positions in Metropolitan City . Metropolitan City headed by elected Mayor (4 Year Term) . Metropolitan City Council Composed of 33 elected Councilmen by districts (4 Year Term) . Prosecutor and Assessor Independently Elected at large 3 Your Logo METRO MAYOR Here . Is a “strong Mayor” form of government . Mayor appoints all department heads who serve at the pleasure of the Mayor . Mayor appoints all members of boards and commissions . Mayor SHALL appoint 4 deputy mayors to be called: o Deputy Mayor for Public Health and Safety o Deputy Mayor for Economic Development and Innovation o Deputy Mayor for Community Development and Housing o Deputy Mayor for Community Engagement and Equity .