The Berkeley Castle Muniments by David Smith 2007, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GLOUCESTER & BRISTOL, a Descriptive Account of Each Place

Hunt & Co.’s Directory March 1849 - Transcription of the entry for Dursley, Gloucestershire Hunt & Co.’s Directory for the Cities of Gloucester and Bristol for March 1849 Transcription of the entry for Dursley and Berkeley, Gloucestershire Background The title page of Hunt & Co.’s Directory & Topography for the Cities of Gloucester and Bristol for March 1849 declares: HUNT & CO.'S DIRECTORY & TOPOGRAPHY FOR THE CITIES OF GLOUCESTER & BRISTOL, AND THE TOWNS OF BERKELEY, CIRENCESTER, COLEFORD, DURSLEY, LYDNEY, MINCHINHAMPTON, MITCHEL-DEAN, NEWENT, NEWNHAM, PAINSWICK, SODBURY, STROUD, TETBURY, THORNBURY, WICKWAR, WOTTON-UNDER-EDGE, &c. W1TH ABERAVON, ABERDARE, BRIDGEND, CAERLEON, CARDIFF, CHEPSTOW, COWBRIDCE, LLANTRISSAINT, MERTHYR, NEATH, NEWBRIDGE, NEWPORT, PORTHCAWL, PORT-TALBOT, RHYMNEY, TAIBACH, SWANSEA, &c. CONTAINING THE NAMES AND ADDRESSES OF The Nobility, Gentry, Clergy, PROFESSIONAL GENTLEMEN, TRADERS, &c. RESlDENT THEREIN. A Descriptive Account of each Place, POST-OFFICE INFORMATION, Copious Lists of the Public Buildings, Law and Public Officers - Particulars of Railroads, Coaches, Carriers, and Water Conveyances - Distance Tables, and other Useful Information. __________________________________________ MARCH 1849. ___________________________________________ Hunt & Co. produced several trade directories in the mid 1850s although the company was not prolific like Pigot and Kelly. The entry for Dursley and Berkeley, which also covered Cambridge, Uley and Newport, gave a comprehensive listing of the many trades people in the area together with a good gazetteer of what the town was like at that time. The entry for Dursley and Berkeley is found on pages 105-116. This transcription was carried out by Andrew Barton of Dursley in 2005. All punctuation and spelling of the original is retained. In addition the basic layout of the original work has been kept, although page breaks are likely to have fallen in different places. -

Records of Bristol Cathedral

BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY’S PUBLICATIONS General Editors: MADGE DRESSER PETER FLEMING ROGER LEECH VOL. 59 RECORDS OF BRISTOL CATHEDRAL 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 RECORDS OF BRISTOL CATHEDRAL EDITED BY JOSEPH BETTEY Published by BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY 2007 1 ISBN 978 0 901538 29 1 2 © Copyright Joseph Bettey 3 4 No part of this volume may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, 5 electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any other information 6 storage or retrieval system. 7 8 The Bristol Record Society acknowledges with thanks the continued support of Bristol 9 City Council, the University of the West of England, the University of Bristol, the Bristol 10 Record Office, the Bristol and West Building Society and the Society of Merchant 11 Venturers. 12 13 BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY 14 President: The Lord Mayor of Bristol 15 General Editors: Madge Dresser, M.Sc., P.G.Dip RFT, FRHS 16 Peter Fleming, Ph.D. 17 Roger Leech, M.A., Ph.D., FSA, MIFA 18 Secretaries: Madge Dresser and Peter Fleming 19 Treasurer: Mr William Evans 20 21 The Society exists to encourage the preservation, study and publication of documents 22 relating to the history of Bristol, and since its foundation in 1929 has published fifty-nine 23 major volumes of historic documents concerning the city. -

Cotswold Landmarks

Cotswold Landmarks Castles in The Cotswolds are not rare, in fact the region has some of the most beautiful castles in England and many are top tourist attractions in the area. Although Blenheim is not a castle, it is still an incredibly beautiful landmark which attracts thousands of visitors every year. The Cotswolds have some of England’s most well-known castles, many that have royal connections and fascinating historical stories. The Cotswolds stretches across the Cotswold hills and is in the South-West of England, just a short trip taking 1 hour and 40 minutes on a train from London. The region is steeped in history and was once the largest supplier of English wool during the Medieval times. The Cotswold hills are magical with breath-taking views across to faraway places such as the Welsh mountains. Berkeley Castle Berkeley Castle is still owned by the Berkeley family and remains a stunning example of English heritage in the beautiful Cotswold countryside. Berkeley Castle was built in 1153 and has welcomed many royals over the centuries including Henry VIII, Edward II, Elizabeth I and the late Queen Mother. There are some incredible and historical stories about the castle, including where the murder of Edward II took place and apparently, Midsummers Night’s Dream by Shakespeare, was written for a Berkeley family wedding within the castle. It is also believed that the last court jester known in England died at Berkeley Castle when he fell from the minstrel’s gallery in the Great Hall. Berkeley Castle is a fine example of typical architecture and English stately culture and is a charming aspect to the beauty of The Cotswolds. -

Law in Action in Medieval England

VIRGINIA LAW REVIEW Vol. XVII NOVEMBER, 1930 No. 1 LAW IN ACTION IN MEDIEVAL ENGLAND ONE reading the skeleton-likereports found in the Year Booksfrom which so muchof thecommon law has filtered throughthe great medieval abridgments down even to thejuris- prudenceof our own timeoften wonders what was theatmos- phereof thecourt room in whichthese cases were argued and thejudgments rendered; and what were the social, economic, and politicalconditions that furnished the setting for the contest and affordedthe stimuli to judicialaction. It is quitetrue, as Pro- fessorBolland has so interestinglyshown,1 that one sometimes discoversin thesereports touches of humaninterest and even incidentsof historicaland sociologicalimportance; but forthe mostpart the Year Booksfurnish little data forthe sociologist and too oftenonly fragmentary and unsatisfactorymaterial for thelegal historian. The apprentices,who for the most part seem to haveindited the Year Bookreports, were primarily interested in therules of procedure.They desired to recordand learnthe correctplea and theappropriate reply, the right word which wouldset thecrude legal machinery of theking's courts in mo- tion. Theymanifested no interestin thephilosophy of law,or in thesocial and economiceffects that might be producedby the judgmentsthey recorded. Veryoften, however, these medieval scribes, these lovers of curiouswords and rigidlegal formulas, did noteven record the judgmentin case it was rendered.This characteristicis strik- EDIrTO'S NoTv.-Our usual policyof documentingeach quotedpassage -

Sir Robert Throckmorton (1510-1581)

Sir Robert Throckmorton (1510-1581) William Norwood, Dorothy Spann CENTER's eighth great grandfather and father of Richard Norwood appearing in the lower right in the tree for Captain Richard Spann, was the son of Henry Norwood and Catherine Thockmorton. Catherine Thockmorton was the daughter of Robert Thockmorton and Muriel Berkeley. Sir Robert Thockmorton: Birth: 1510 Alcester; Warwickshire, England Death: Feb. 12, 1581 Alcester; Warwickshire, England St Peters Church, Coughton, Warwickshire, England where he is buried. Sir Robert Throckmorton of Coughton Court, was a distinguished English Tudor courtier. Sir Robert was the eldest son and heir of Sir George Throckmorton (d.1552) by Katherine Vaux, daughter of Nicholas Vaux, 1st Baron Vaux of Harrowden (d.1523). He had many brothers, the most notable being, in descending seniority: Sir Kenelm, Sir Clement Throckmorton MP, Sir Nicholas Throckmorton(1515-1571), Thomas, Sir John Throckmorton(1524-1580), Anthony and George. Robert Throckmorton may have trained at the Middle Temple, the inn attended by his father. At least three of his younger brothers and his own eldest son studied at Middle Temple, but as the heir to extensive estates he had little need to seek a career at court or in government. He was joined with his father in several stewardships from 1527 and was perhaps the servant of Robert Tyrwhitt, a distant relative by marriage of the Throckmortons, who in 1540 took an inventory of Cromwell's goods at Mortlake. He attended the reception of Anne of Cleves and with several of his brothers served in the French war of 1544. Three years later he was placed on the Warwickshire bench and in 1553 was appointed High Sheriff of Warwickshire. -

Saint Jordan of Bristol: from the Catacombs of Rome to College

THE BRISTOL BRANCH OF THE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION LOCAL HISTORY PAMPHLETS SAINT JORDAN OF B�ISTOL: FROM THE CATACOMBS OF ROME Hon. General Editor: PETER HARRIS TO COLLEGE GREEN AT BRISTOL Assistant General Editor: NORMA KNIGHT Editorial Advisor: JOSEPH BETTEY THE CHAPEL OF ST JORDAN ON COLLEGE GREEN Intercessions at daily services in Bristol Cathedral conclude with the Saint Jordan of Bristol: from the Cataconibs of Rome to College Green at following act of commitment and memorial: Bristol is the one hundred and twentieth pamphlet in this series. We commit ourselves, one another and our whole life to Christ David Higgins was Head of the Department of Italian Studies at the our God ... remembering all who have gone before us in faith, and University of Bristol until retirement in 1995. His teaching and research in communion with Mary, the Apostles Peter and Paul, Augustine embraced the political, cultural and linguistic history of Italy in its and Jordan and all the Saints. Mediterranean and European contexts from the Late Roman Period to the Patron Saints of a city, as opposed to a country, are a matter of local Middle Ages, while his publications include Dante: The Divine Comedy choice and tradition - in England he or she is normally the patron saint (Oxford World's Classics 1993) as well as articles in archaeological journals of the city's Cathedral: St Paul (London), St Augustine (Canterbury), St Mary on the Roman and Anglo-Saxon periods of the Bristol area, and in this and St Ethelbert (Hereford); while St David of Wales and St Andrew of series The History of the Bristol Region in the Roman Period and The· Scotland gave their names to the cities in question. -

The Church That Is Now Bristol Cathedral Was Originally An

Bristol Cathedral – architectural overview Jon Cannon – Keeper of the Fabric Overview This paper briefly sets out the history of Bristol Cathedral, by summarising the key events and figures which have shaped its past, and by identifying the main architectural and artistic features of interest. Bristol cathedral is the seat of the bishop of Bristol and the heart of a diocese which, today, includes Bristol, and much of south Gloucestershire and northern Wiltshire, including Swindon. It stands on a site which has been sacred for a thousand years or more. Ancient origins The cathedral originated as an abbey on the edge of what was, in the twelfth century, a prosperous and growing merchant town. The knoll on which it stands appears to already have already been the site of a holy place: the cult of St Jordan, the legend of which, only attested in the fourteenth century, takes the story of site back to St Augustine of Canterbury and the earliest days of English Christianity, and the survival of a magnificent eleventh-century sculpted stone, now in the cathedral, is proof that a church of some kind predated the abbey. Foundation of the abbey began in 1140. Large portions of the resulting church – especially the remarkable chapter house -- survive to this day. The monastery was a daughter house of the Augustinian abbey of St- Victor in Paris though almost nothing is known of its earliest canons. For the next four hundred years it was, while never of dominant significance in the town, by some distance its largest religious institution, as well as being the most important Victorine house in England (and one of the wealthiest Augustinian houses of any kind). -

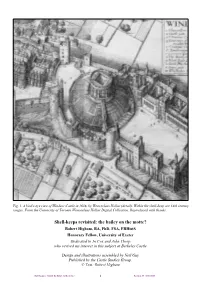

Shell Keeps at Carmarthen Castle and Berkeley Castle

Fig. 1. A bird's-eye view of Windsor Castle in 1658, by Wenceslaus Hollar (detail). Within the shell-keep are 14th century ranges. From the University of Toronto Wenceslaus Hollar Digital Collection. Reproduced with thanks. Shell-keeps revisited: the bailey on the motte? Robert Higham, BA, PhD, FSA, FRHistS Honorary Fellow, University of Exeter Dedicated to Jo Cox and John Thorp, who revived my interest in this subject at Berkeley Castle Design and illustrations assembled by Neil Guy Published by the Castle Studies Group. © Text: Robert Higham Shell-keeps re-visited: the bailey on the motte? 1 Revision 19 - 05/11/2015 Fig. 2. Lincoln Castle, Lucy Tower, following recent refurbishment. Image: Neil Guy. Abstract Scholarly attention was first paid to the sorts of castle ● that multi-lobed towers built on motte-tops discussed here in the later 18th century. The “shell- should be seen as a separate form; that truly keep” as a particular category has been accepted in circular forms (not on mottes) should be seen as a academic discussion since its promotion as a medieval separate form; design by G.T. Clark in the later 19th century. Major ● that the term “shell-keep” should be reserved for works on castles by Ella Armitage and A. Hamilton mottes with structures built against or integrated Thompson (both in 1912) made interesting observa- with their surrounding wall so as to leave an open, tions on shell-keeps. St John Hope published Windsor central space with inward-looking accommodation; Castle, which has a major example of the type, a year later (1913). -

Biographical Appendix

Biographical Appendix The following women are mentioned in the text and notes. Abney- Hastings, Flora. 1854–1887. Daughter of 1st Baron Donington and Edith Rawdon- Hastings, Countess of Loudon. Married Henry FitzAlan Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk, 1877. Acheson, Theodosia. 1882–1977. Daughter of 4th Earl of Gosford and Louisa Montagu (daughter of 7th Duke of Manchester and Luise von Alten). Married Hon. Alexander Cadogan, son of 5th Earl of Cadogan, 1912. Her scrapbook of country house visits is in the British Library, Add. 75295. Alten, Luise von. 1832–1911. Daughter of Karl von Alten. Married William Montagu, 7th Duke of Manchester, 1852. Secondly, married Spencer Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, 1892. Grandmother of Alexandra, Mary, and Theodosia Acheson. Annesley, Katherine. c. 1700–1736. Daughter of 3rd Earl of Anglesey and Catherine Darnley (illegitimate daughter of James II and Catherine Sedley, Countess of Dorchester). Married William Phipps, 1718. Apsley, Isabella. Daughter of Sir Allen Apsley. Married Sir William Wentworth in the late seventeenth century. Arbuthnot, Caroline. b. c. 1802. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. She did not marry. Arbuthnot, Marcia. 1804–1878. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. Married William Cholmondeley, 3rd Marquess of Cholmondeley, 1825. Aston, Barbara. 1744–1786. Daughter and co- heir of 5th Lord Faston of Forfar. Married Hon. Henry Clifford, son of 3rd Baron Clifford of Chudleigh, 1762. Bannister, Henrietta. d. 1796. Daughter of John Bannister. She married Rev. Hon. Brownlow North, son of 1st Earl of Guilford, 1771. Bassett, Anne. Daughter of Sir John Bassett and Honor Grenville. -

Huguenot Merchants Settled in England 1644 Who Purchased Lincolnshire Estates in the 18Th Century, and Acquired Ayscough Estates by Marriage

List of Parliamentary Families 51 Boucherett Origins: Huguenot merchants settled in England 1644 who purchased Lincolnshire estates in the 18th century, and acquired Ayscough estates by marriage. 1. Ayscough Boucherett – Great Grimsby 1796-1803 Seats: Stallingborough Hall, Lincolnshire (acq. by mar. c. 1700, sales from 1789, demolished first half 19th c.); Willingham Hall (House), Lincolnshire (acq. 18th c., built 1790, demolished c. 1962) Estates: Bateman 5834 (E) 7823; wealth in 1905 £38,500. Notes: Family extinct 1905 upon the death of Jessie Boucherett (in ODNB). BABINGTON Origins: Landowners at Bavington, Northumberland by 1274. William Babington had a spectacular legal career, Chief Justice of Common Pleas 1423-36. (Payling, Political Society in Lancastrian England, 36-39) Five MPs between 1399 and 1536, several kts of the shire. 1. Matthew Babington – Leicestershire 1660 2. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1685-87 1689-90 3. Philip Babington – Berwick-on-Tweed 1689-90 4. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1800-18 Seat: Rothley Temple (Temple Hall), Leicestershire (medieval, purch. c. 1550 and add. 1565, sold 1845, remod. later 19th c., hotel) Estates: Worth £2,000 pa in 1776. Notes: Four members of the family in ODNB. BACON [Frank] Bacon Origins: The first Bacon of note was son of a sheepreeve, although ancestors were recorded as early as 1286. He was a lawyer, MP 1542, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal 1558. Estates were purchased at the Dissolution. His brother was a London merchant. Eldest son created the first baronet 1611. Younger son Lord Chancellor 1618, created a viscount 1621. Eight further MPs in the 16th and 17th centuries, including kts of the shire for Norfolk and Suffolk. -

Cotswold Castles

Cotswold Castles Castles in The Cotswolds are not unusual, in fact the area is home to some of the most beautiful castles in England. Many are top of the tourist attractions in the region. There is also Blenheim Palace which although is not a castle, remains a popular tourist attraction, one of the most stunning and magnificent homes in The Cotswolds. The Cotswolds have some of England’s most famous and majestic castles, many with interesting royal connections and historical reports attached. The region stretches across the Cotswold hills in the South- West of England and is only 1 hour and 40 minutes if you are catching a train from London. Steeped in unusual history, the Cotswolds was once famous for being one of the largest areas that contributed to the output of English wool during the Medieval times. It is well-known for ‘The Cotswold Way’, a pretty one hundred miles walk with magnificent breath-taking views that trails along the Cotswold hills. Berkeley Castle Berkeley Castle has greeted royals over the centuries including Edward II, Henry VIII, Elizabeth I and the late Queen Mother. The castle was built in 1153 and still belongs to the Berkeley family, remaining a beautiful example of English heritage in the pretty Cotswold countryside. There are many interesting and historical stories about the castle, including that supposedly the murder of Edward II happened there and Midsummers Night’s Dream by Shakespeare was written for a Berkeley family wedding at the castle. The last court jester known in apparently England died at the castle in the Great Hall when he fell from the minstrel’s gallery. -

Starter Activities

Gloucestershire Archives Take One Castle GLOUCESTERSHIRE ARCHIVES TAKE ONE CASTLE - PRIMARY TEACHERS’ NOTES INTRODUCTION This resource is intended to allow teachers to use the Gloucester Castle accounts roll in an inspiring, cross-curricular way. It is based on the National Gallery’s Take One Picture programme (see: www.takeonepicture.org.uk), which promotes the use of one picture as a rich and accessible source for cross-curricular learning. The Take One approach follows three stages: imagination, evidence and pupil-led learning. The Take One model was adopted for the use of archive documents by Gloucestershire Archives after the Take One Prisoner project funded by the MLA (Museums, Libraries & Archives) Council. ABOUT THE DOCUMENT The Gloucester castle account roll (Gloucestershire Archives Reference: D4431/2/56/1) is a list of the financial expenditure on the castle that was undertaken by the King’s Custodian of Gloucester castle, Sir Roger de Clifford, from December 1263 to March 1266. It was compiled by de Clifford as a record of the expenditure he undertook to strengthen the castle and its defences as ordered by Prince Edward when he was present in the castle in March 1262. This roll is an original document that was part of the collection of Sir Thomas Phillipps, a 19th century antiquary of Gloucestershire and which is now held at Gloucestershire Archives. Gloucestershire Archives Take One Castle A transcript in English was created in 1976 by Mrs M Watson of Painswick and is also held at Gloucestershire Archives under the reference GMS 152. There exists a shorter duplicate copy of the roll (which omits the names and details of the building works), that was created by a government official in the Crown’s Exchequer soon after the original had been written.