Memo on the Safeguarding American Innovation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tax News & Views

Tax News & Views Capitol Hill briefing. May 14, 2021 In this issue: White House continues bipartisan outreach on infrastructure package ................................................................ 1 Capital gains, estate taxes dominate debate at Ways and Means Select Revenue Measures hearing .................. 6 Senate taxwriters wrestle with tax gap, audit and enforcement issues ............................................................... 11 House panel OKs proposal to require country-by-country financial reporting .................................................... 13 White House continues bipartisan outreach on infrastructure package President Biden held several meetings this week with prominent congressional Democrats and Republicans who may prove key to the fate of his infrastructure agenda, but it remains unclear whether any package will be moved on a bipartisan basis or with the support of only Democrats. In recent weeks, the president has proposed two massive packages of spending and tax proposals to overhaul the nation’s physical infrastructure and what the administration has dubbed the nation’s “human” infrastructure. Tax News & Views Page 1 of 14 Copyright © 2021 Deloitte Development LLC May 14, 2021 All rights reserved. Biden’s American Jobs Plan calls for investing an estimated $2.7 trillion (over eight years) in transportation infrastructure, broadband, the electric grid, water systems, schools, manufacturing, renewable energy, and more, and would be paid for largely through increased taxes on corporations and, in particular, US multinationals. (For details, see Tax News & Views, Vol. 22, No. 19, Apr. 9, 2021.) URL: https://dhub.blob.core.windows.net/dhub/Newsletters/Tax/2021/TNV/210409_1.html The president’s American Families Plan calls for $1.8 trillion over 10 years in proposed spending and tax credits in areas such as education, child care, health care, and paid family leave, and would be paid for primarily with tax increases on taxpayers earning more than $400,000 per year. -

5 Takeaways from Bipartisan Buyamerican.Gov Bill by Justin Ganderson, Sandy Hoe and Jeff Bozman (January 25, 2018, 12:59 PM EST)

Portfolio Media. Inc. | 111 West 19th Street, 5th Floor | New York, NY 10011 | www.law360.com Phone: +1 646 783 7100 | Fax: +1 646 783 7161 | [email protected] 5 Takeaways From Bipartisan BuyAmerican.gov Bill By Justin Ganderson, Sandy Hoe and Jeff Bozman (January 25, 2018, 12:59 PM EST) On Jan. 9, 2018, Sen. Chris Murphy, D-Ct., proudly announced via Twitter that there now is “bipartisan support for strengthening our Buy American laws” and that he is “excited to have the Trump admin[istration] and partners like [Sens. Rob Portman, R-Ohio, Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., and Sherrod Brown, D-Ohio] working together to get this done.”[1] That same day, these senators reached across the aisle to sponsor the BuyAmerican.gov Act of 2018 (S.2284) to “strengthen Buy American requirements.”[2] This proposed legislation may be the most significant “Buy American” development since President Donald Trump issued his April 2017 “Buy American” executive order Justin Ganderson (E.O. 13788), which set forth a policy and action plan to “maximize ... the use of goods, products and materials produced in the United States” through federal procurements and federal financial assistance awards to “support the American manufacturing and defense industrial bases.”[3] At its heart, the bill would formally recognize President Trump’s “Buy American” policy, require certain reporting and assessments, and limit the use of waivers/exceptions. And even if the bill ultimately is not signed into law, this bipartisan effort suggests that some form of “Buy American” action looms on the horizon. Key Components of the Proposed BuyAmerican.gov Act of 2018 Sandy Hoe Borrowing heavily from President Trump’s “Buy American” executive order, the bipartisan BuyAmerican.gov Act of 2018 aims to “strengthen Buy American requirements” in any domestic preference law, regulation, rule or executive order relating to federal contracts or grants, including: the Buy American Act (41 U.S.C. -

March 2019 with President Trump Signing Funding Legislation in Late

Having trouble reading this email? View it in your browser March 2019 SHARE THIS With President Trump signing funding legislation in late January to reopen the government, both Congress and the Executive Branch have turned their attention back to a litany of other agenda items. Chief among these issues will be funding for Fiscal Year (FY) 2020, which legislators will need to secure before current government funding runs out at the end of the fiscal year on September 30. The FY 2020 appropriations process will begin in earnest on March 11 as President Trump unveiled his budget for the fiscal year. The President’s budget is a starting point for lawmakers in Congress, who will begin negotiating topline levels for government spending. One complicating factor is the potential return of budget sequestration. Under The Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA), budget caps are set to come back into force for Fiscal Years 2020 and 2021, absent congressional action and enforced by an acrossthegovernment process of spending cuts known as sequestration. Already, conversations are underway among budget and appropriations leaders on how to lift the austere budget caps and avert sequestration. Another issue that has reemerged for Congress is how to proceed with the statutory limit on U.S. debt, known as the debt ceiling. The debt ceiling was suspended until March 1, per legislation signed by the President in February 2018. Though the debt ceiling has been reached, the U.S. Treasury (Treasury) has “extraordinary measures” it can use to delay actual default on the federal debt. However, those measures are likely to run out sometime in late summer or early fall, and Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin has called on Congress to pass a debt ceiling extension as soon as possible. -

Ranking Member John Barrasso

Senate Committee Musical Chairs August 15, 2018 Key Retiring Committee Seniority over Sitting Chair/Ranking Member Viewed as Seat Republicans Will Most Likely Retain Viewed as Potentially At Risk Republican Seat Viewed as Republican Seat at Risk Viewed as Seat Democrats Will Most Likely Retain Viewed as Potentially At Risk Democratic Seat Viewed as Democratic Seat at Risk Notes • The Senate Republican leader is not term-limited; Senator Mitch McConnell (R-KY) will likely remain majority leader. The only member of Senate GOP leadership who is currently term-limited is Republican Whip John Cornyn (R-TX). • Republicans have term limits of six years as chairman and six years as ranking member. Republican members can only use seniority to bump sitting chairs/ranking members when the control of the Senate switches parties. • Committee leadership for the Senate Aging; Agriculture; Appropriations; Banking; Environment and Public Works (EPW); Health Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP); Indian Affairs; Intelligence; Rules; and Veterans Affairs Committees are unlikely to change. Notes • Current Armed Services Committee (SASC) Chairman John McCain (R-AZ) continues to receive treatment for brain cancer in Arizona. Senator James Inhofe (R-OK) has served as acting chairman and is likely to continue to do so in Senator McCain’s absence. If Republicans lose control of the Senate, Senator McCain would lose his top spot on the committee because he already has six years as ranking member. • In the unlikely scenario that Senator Chuck Grassley (R-IA) does not take over the Finance Committee, Senator Mike Crapo (R-ID), who currently serves as Chairman of the Banking Committee, could take over the Finance Committee. -

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION DOLLAR & SENSE PODCAST Sen

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION DOLLAR & SENSE PODCAST Sen. Tom Carper on the trade issues confronting America Monday, June 15, 2020 DAVID DOLLAR Senior Fellow, Foreign Policy and Global Economy and Development Programs and the John L. Thornton China Center The Brookings Institution THE HON. TOM CARPER U.S. Senate (D-DE) * * * * * DOLLAR: Hi, I'm David Dollar, host of the Brookings trade podcast, "Dollars & Sense." Today my guest is Senator Tom Carper, Democrat of Delaware. Among other things, the senator is and members of the Senate Finance Committee which deals with trade issues. We're going to talk about some of the key trade issues facing America and issues that Congress is dealing with. So, thank you very much for joining the show, Senator. SEN. CARPER: David, great to see you. Thanks so much. DOLLAR: So one of the important trade issues right now concerns Hong Kong. The United States has accorded special status to Hong Kong even though it's part of the larger People's Republic of China, but now that Beijing is encroaching on civil liberties there our administration is considering taking away the special status. It actually consists of a lot of different specific things – an extradition treaty, different tariffs for Hong Kong goods, we have very deep financial integration – so to some extent we can pick and choose. The challenge, it seems to me, is that we don't want to hurt the people of Hong Kong, but we are interested in making some kind of statement and trying to influence Beijing. So can I ask: What are your views on what we should be doing with Hong Kong's special status? SEN. -

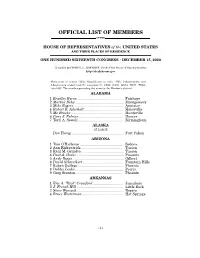

Official List of Members

OFFICIAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES of the UNITED STATES AND THEIR PLACES OF RESIDENCE ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS • DECEMBER 15, 2020 Compiled by CHERYL L. JOHNSON, Clerk of the House of Representatives http://clerk.house.gov Democrats in roman (233); Republicans in italic (195); Independents and Libertarians underlined (2); vacancies (5) CA08, CA50, GA14, NC11, TX04; total 435. The number preceding the name is the Member's district. ALABAMA 1 Bradley Byrne .............................................. Fairhope 2 Martha Roby ................................................ Montgomery 3 Mike Rogers ................................................. Anniston 4 Robert B. Aderholt ....................................... Haleyville 5 Mo Brooks .................................................... Huntsville 6 Gary J. Palmer ............................................ Hoover 7 Terri A. Sewell ............................................. Birmingham ALASKA AT LARGE Don Young .................................................... Fort Yukon ARIZONA 1 Tom O'Halleran ........................................... Sedona 2 Ann Kirkpatrick .......................................... Tucson 3 Raúl M. Grijalva .......................................... Tucson 4 Paul A. Gosar ............................................... Prescott 5 Andy Biggs ................................................... Gilbert 6 David Schweikert ........................................ Fountain Hills 7 Ruben Gallego ............................................ -

Tom Carper (D-De)

LEGISLATOR US Senator TOM CARPER (D-DE) IN OFFICE CONTACT Up for re-election in 2018 Email Contact Form http://www.carper.senate. 3rd Term gov/public/index.cfm/ Re-elected in 2012 email-senator-carper SENIORITY RANK Web www.carper.senate.gov 24 http://www.carper.senate. gov Out of 100 Twitter @senatorcarper https://twitter.com/ senatorcarper Facebook View on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/ tomcarper DC Office 513 Hart Senate Office Building BGOV BIOGRAPHY By Brian Nutting, Bloomberg News Tom Carper, described even by foes as a nice guy, makes an effort to seek bipartisan solutions to the nation’s problems and tries to work out differences on legislation in private consultations rather than fighting it out in public in committee or on the floor. Carper has been in public office since 1977, including 10 years in the House and two terms as Delaware’s governor before coming to the Senate. He says on his congressional website that he has “earned a reputation as a results-oriented centrist.” Still, his congressional voting record places him on the liberal side of the political spectrum, with a rating of about 90 percent from th Americans for Democratic Action and about 10 percent from the American Conservative Union. During his tenure on Capitol Hill, he has broken with party ranks a little more often than the average Democratic lawmaker, although not so much in the 113th Congress. He touts the virtues of pragmatism and bipartisanship. He’s a founder of the Third Way, a policy group that says its mission “is to advance moderate policy and political ideas,” and affiliates also with the Moderate Democrats Working Group, a group of about a dozen Senate Democrats, and the Democratic Leadership Council. -

117Th Congress (2021) Committee Report Card

117th Congress (2021) Committee Report Card Rank Chair Committee Score Grade 1 Rosa DeLauro (D-CT) House Committee on Appropriations 184% A 2 Ron Wyden (D-OR) Senate Committee on Finance 136% A 3 Jack Reed (D-RI) Senate Committee on Armed Services 131% A 4 Patrick Leahy (D-VT) Senate Committee on Appropriations 124% A 5 Adam Smith (D-WA) House Committee on Armed Services 116% A 6 Raúl Grijalva (D-AZ) House Committee on Natural Resources 102% A 7 Maxine Waters (D-CA) House Committee on Financial Services 101% A 8 Bobby Scott (D-VA) House Committee on Education and Labor 97% A 9 Jon Tester (D-MT) Senate Committee on Veterans' Affairs 87% B 10 John Yarmuth (D-KY) House Committee on Budget 76% C 11 Mark Takano (D-CA) House Committee on Veterans' Affairs 75% C 11 Joe Manchin (D-WV) Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources 75% C 13 Patty Murray (D-WA) Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions 73% C 14 Sherrod Brown (D-OH) Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs 64% D 15 Dick Durbin (D-IL) Senate Committee on Judiciary 60% D- 16 Nydia Velázquez (D-NY) House Committee on Small Business 59% F 17 Bob Menendez (D-NJ) Senate Committee on Foreign Relations 58% F 18 David Scott (D-GA) House Committee on Agriculture 57% F 19 Frank Pallone (D-NJ) House Committee on Energy and Commerce 56% F 20 Jerrold Nadler (D-NY) House Committee on Judiciary 54% F 21 Gregory Meeks (D-NY) House Committee on Foreign Affairs 53% F 21 Bennie Thompson (D-MS) House Committee on Homeland Security 53% F 21 Ben Cardin (D-MD) Senate Committee -

Burying the Hatchet for Two Centuries

200 YEARS OF SUSSEX COUNTY TRADITION Return Day There is no doubt it's one of the most unusual events in the nation: people gather two days after the election to listen to returns, support the winners and console the losers. Burying the hatchet – literally – is the overriding theme of the event. People wait in line for a piece of roast ox in the 1960 Return Day. Russell Peterson, who served the state as governor from 1968- PHOTOS COURTESY OF SUSSEX COUNTY RETURN DAY 72, waves to a crowd lining The Circle in downtown George- THIS IS ONE OF THE EARLIEST known photographs of Return Day. Even in 1908, it's easy to see the day was a festive one. town. Peterson changed from Republican to Democrat in 1996. Festivities start the night before around The Circle with entertainment and food Many happy returns: Burying vendors, and revelry continues through- out Return Day into the night as busi- nesses and lawyers host open houses. Over the years, entertainment, vendors the hatchet for two centuries and an oxen roast have been added to the event. By Ron MacArthur the date can't be confirmed. and bury it in a box of sand brought in State law in 1791 moved the county seat [email protected] There are two accounts about early Re- from Rehoboth Beach specifically for the from Lewes to a town later named turn Days published in an 1860 New York event. Georgetown; that law also required all ith an event as steeped in Tribune newspaper article and in an 1888 Winners and losers ride together in voters to cast their ballots in the county tradition as Return Day, al- book about the history of Delaware. -

Sen. Tom Carper (D-DE)

Sen. Tom Carper (D-DE) Official Photo Navy League Advocates in State 108 Previous Contacts 13 Grassroots Actions Since July 2020 0 Address Room 513 Hart Senate Office Building Washington, DC 20510-0803 Elected Next Election Term 2000 2024 4th term Before Politics Education Public Official, Military University of Delaware, Newark M.B.A. 1975 Education Past Military Service Ohio State University B.A. 1968 U.S. Naval Reserve, CDR, 1973-1992 Bio Sen. Tom Carper is a 4th term Senator in the US Congress who represents Delaware and received 60.0% of the vote in his last election. He is the Ranking Member of the Environment committee, and a member of the Homeland Security and Finance committees.He works most frequently on Tariffs (148 bills), Foreign Trade and International Finance (148 bills), International Affairs (115 bills), International finance and foreign exchange (108 bills), and Government information and archives (69 bills). He has sponsored 330 bills in his last thirty-seven year(s) in office, voting with his party 87.6% of the time, getting 19.09% of Sea Service Installations in State: Co-Sponsored Bills We Support Born in West Virginia and raised in Virginia, Senator Tom S. 133: Merchant Mariners of World War II Carper attended The Ohio State University on a Navy R.O.T.C. scholarship, graduating in 1968 with a B.A. in economics. He went on to complete five years of service as a naval flight officer, serve three tours of duty in… Powered by Quorum Sen. Tom Carper (D-DE) Committees Senate Committee on Finance Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works Subcommittees Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations Senate Subcommittee on Energy, Natural Resources, Senate Subcommittee on Health Care Senate Subcommittee on Regulatory Affairs and Federal Senate Subcommittee on Taxation and IRS Oversight Powered by Quorum. -

2018 Primary Election Results Analysis OAEPS | Baldwin Wallace

ANOTHER “YEAR OF THE WOMAN?” WOMEN RUNNING FOR PUBLIC OFFICE IN OHIO IN THE 2018 MIDTERM ELECTIONS BARBARA PALMER Professor of Political Science Department of Politics and Global Citizenship Executive Director & Creator, Center for Women & Politics of Ohio Baldwin Wallace University Berea, OH [email protected] Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Ohio Association of Economists and Political Scientists, Capitol University, Columbus OH, September, 2018 1 ANOTHER “YEAR OF THE WOMAN?” WOMEN RUNNING FOR PUBLIC OFFICE IN OHIO IN THE 2018 MIDTERM ELECTIONS1 The 2018 midterm election has been commonly referred to as another “Year of the Woman.” There is already a great deal of evidence that this election cycle will be a record year for female candidates. For example, in Georgia, Stacey Abrams defeated another woman, Stacey Evans, to win the Democratic primary for governor; Abrams is the first African American woman to ever be a major-party nominee for governor in US history. In addition, a record number of women have filed to run for US House (“2018 Summary”). Women are opening their pocket books in record numbers: in 2014, the last midterm election, 198,000 women contributed $200 or more to a federal campaign or political action committee. By July of 2018, three months before the midterm election, 329,000 women had contributed, and they were contributing to female candidates (Bump, 2018). As one political commentator explained, “As the midterms near, there are signs that an energized base of women will play a significant — and probably defining — role in the outcome” (Bump, 2018). This paper will explore the trends in women running for public office in Ohio; more specifically, are we seeing an increase in the number of women running for US Congress, state legislature, governor and other state-wide offices? In 1992, the original “Year of the Woman,” we saw a spike in the number of female candidates across the nation at the state and national level. -

Delaware Republicans Losing House Seat

For release… Tuesday, Oct. 5, 2010… 4 pages Contacts: Peter Woolley 973.670.3239; Dan Cassino 973.896.7072 Delaware Republicans Losing House Seat Likely voters in Delaware split 45%-40% on whether they prefer to have the U.S. Congress controlled by the Democratic Party or the Republican Party, suggesting that the First State’s open congressional seat might be hotly contested. But according to the most recent poll by Fairleigh Dickinson University’s PublicMind, Democrat and former Lt. Gov. John Carney is leading Republican Glen Urquhart by 51%-36% for the House seat soon to be vacated by Republican Mike Castle. “Reputation and name brand matter,” said Peter Woolley, professor of political science at Fairleigh Dickinson University and director of the poll, “and it matters a little more in Delaware than in most states,” he said. While Carney predictably leads comfortably in New Castle County (56-32), he runs even with Urquhart (43-43) in the more Republican counties of Kent and Sussex. “The idea of wanting a change in party control in Washington doesn’t line up neatly with preferences in each congressional district,” said Woolley. “Candidates matter, not just parties.” But it is Beau Biden who wins the popularity contest in the state promoted as the Small Wonder, with 61% of likely voters offering a favorable opinion of him against 23% with an unfavorable opinion. Biden’s only opponent for attorney general, independent Doug Campbell, is unknown by 81% of voters and another 12% have no opinion of him. Biden leads Campbell 65%-25%. In the race for state treasurer, Democrat Chip Flowers and Republican Colin Bonini are neck and neck at 38%-38%, with 21% unsure.