Large Fluctuations in the Sardine Fishery in the Gulf of California: Possible Causes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coastal Processes and Causes of Shoreline Erosion and Accretion Causes of Shoreline Erosion and Accretion

Coastal Processes and Causes of Shoreline Erosion and Accretion and Accretion Erosion Causes of Shoreline Heather Weitzner, Great Lakes Coastal Processes and Hazards Specialist Photo by Brittney Rogers, New York Sea Grant York Photo by Brittney Rogers, New New York Sea Grant Waves breaking on the eastern Lake Ontario shore. Wayne County Cooperative Extension A shoreline is a dynamic environment that evolves under the effects of both natural 1581 Route 88 North and human influences. Many areas along New York’s shorelines are naturally subject Newark, NY 14513-9739 315.331.8415 to erosion. Although human actions can impact the erosion process, natural coastal processes, such as wind, waves or ice movement are constantly eroding and/or building www.nyseagrant.org up the shoreline. This constant change may seem alarming, but erosion and accretion (build up of sediment) are natural phenomena experienced by the shoreline in a sort of give and take relationship. This relationship is of particular interest due to its impact on human uses and development of the shore. This fact sheet aims to introduce these processes and causes of erosion and accretion that affect New York’s shorelines. Waves New York’s Sea Grant Extension Program Wind-driven waves are a primary source of coastal erosion along the Great provides Equal Program and Lakes shorelines. Factors affecting wave height, period and length include: Equal Employment Opportunities in 1. Fetch: the distance the wind blows over open water association with Cornell Cooperative 2. Length of time the wind blows Extension, U.S. Department 3. Speed of the wind of Agriculture and 4. -

Hydrogeology of Near-Shore Submarine Groundwater Discharge

Hydrogeology and Geochemistry of Near-shore Submarine Groundwater Discharge at Flamengo Bay, Ubatuba, Brazil June A. Oberdorfer (San Jose State University) Matthew Charette, Matthew Allen (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution) Jonathan B. Martin (University of Florida) and Jaye E. Cable (Louisiana State University) Abstract: Near-shore discharge of fresh groundwater from the fractured granitic rock is strongly controlled by the local geology. Freshwater flows primarily through a zone of weathered granite to a distance of 24 m offshore. In the nearshore environment this weathered granite is covered by about 0.5 m of well-sorted, coarse sands with sea water salinity, with an abrupt transition to much lower salinity once the weathered granite is penetrated. Further offshore, low-permeability marine sediments contained saline porewater, marking the limit of offshore migration of freshwater. Freshwater flux rates based on tidal signal and hydraulic gradient analysis indicate a fresh submarine groundwater discharge of 0.17 to 1.6 m3/d per m of shoreline. Dissolved inorganic nitrogen and silicate were elevated in the porewater relative to seawater, and appeared to be a net source of nutrients to the overlying water column. The major ion concentrations suggest that the freshwater within the aquifer has a short residence time. Major element concentrations do not reflect alteration of the granitic rocks, possibly because the alteration occurred prior to development of the current discharge zones, or from elevated water/rock ratios. Introduction While there has been a growing interest over the last two decades in quantifying the discharge of groundwater to the coastal zone, the majority of studies have been carried out in aquifers consisting of unlithified sediments or in karst environments. -

Physical Geography of Southeast Asia

Physical Geography of Southeast Asia Creating an Annotated Sketch Map of Southeast Asia By Michelle Crane Teacher Consultant for the Texas Alliance for Geographic Education Texas Alliance for Geographic Education; http://www.geo.txstate.edu/tage/ September 2013 Guiding Question (5 min.) . What processes are responsible for the creation and distribution of the landforms and climates found in Southeast Asia? Texas Alliance for Geographic Education; http://www.geo.txstate.edu/tage/ September 2013 2 Draw a sketch map (10 min.) . This should be a general sketch . do not try to make your map exactly match the book. Just draw the outline of the region . do not add any features at this time. Use a regular pencil first, so you can erase. Once you are done, trace over it with a black colored pencil. Leave a 1” border around your page. Texas Alliance for Geographic Education; http://www.geo.txstate.edu/tage/ September 2013 3 Texas Alliance for Geographic Education; http://www.geo.txstate.edu/tage/ September 2013 4 Looking at your outline map, what two landforms do you see that seem to dominate this region? Predict how these two landforms would affect the people who live in this region? Texas Alliance for Geographic Education; http://www.geo.txstate.edu/tage/ September 2013 5 Peninsulas & Islands . Mainland SE Asia consists of . Insular SE Asia consists of two large peninsulas thousands of islands . Malay Peninsula . Label these islands in black: . Indochina Peninsula . Sumatra . Label these peninsulas in . Java brown . Sulawesi (Celebes) . Borneo (Kalimantan) . Luzon Texas Alliance for Geographic Education; http://www.geo.txstate.edu/tage/ September 2013 6 Draw a line on your map to indicate the division between insular and mainland SE Asia. -

Baja California Sur, Mexico)

Journal of Marine Science and Engineering Article Geomorphology of a Holocene Hurricane Deposit Eroded from Rhyolite Sea Cliffs on Ensenada Almeja (Baja California Sur, Mexico) Markes E. Johnson 1,* , Rigoberto Guardado-France 2, Erlend M. Johnson 3 and Jorge Ledesma-Vázquez 2 1 Geosciences Department, Williams College, Williamstown, MA 01267, USA 2 Facultad de Ciencias Marinas, Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, Ensenada 22800, Baja California, Mexico; [email protected] (R.G.-F.); [email protected] (J.L.-V.) 3 Anthropology Department, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA 70018, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-413-597-2329 Received: 22 May 2019; Accepted: 20 June 2019; Published: 22 June 2019 Abstract: This work advances research on the role of hurricanes in degrading the rocky coastline within Mexico’s Gulf of California, most commonly formed by widespread igneous rocks. Under evaluation is a distinct coastal boulder bed (CBB) derived from banded rhyolite with boulders arrayed in a partial-ring configuration against one side of the headland on Ensenada Almeja (Clam Bay) north of Loreto. Preconditions related to the thickness of rhyolite flows and vertical fissures that intersect the flows at right angles along with the specific gravity of banded rhyolite delimit the size, shape and weight of boulders in the Almeja CBB. Mathematical formulae are applied to calculate the wave height generated by storm surge impacting the headland. The average weight of the 25 largest boulders from a transect nearest the bedrock source amounts to 1200 kg but only 30% of the sample is estimated to exceed a full metric ton in weight. -

Summer: Environmental Pedology

A SOIL AND VOLUME 13 WATER SCIENCE NUMBER 2 DEPARTMENT PUBLICATION Myakka SUMMER 2013 Environmental Pedology: Science and Applications contents Pedological Overview of Florida 2 Soils Pedological Research and 3 Environmental Applications Histosols – Organic Soils of Florida 3 Spodosols - Dominant Soil Order of 4 Florida Hydric Soils 5 Pedometrics – Quantitative 6 Environmental Soil Sciences Soils in the Earth’s Critical Zone 7 Subaqueous Soils abd Coastal 7 Ecosystems Faculty, Staff, and Students 8 From the Chair... Pedology is the study of soils as they occur on the landscape. A central goal of pedological research is improve holistic understanding of soils as real systems within agronomic, ecological and environmental contexts. Attaining such understanding requires integrating all aspects of soil science. Soil genesis, classification, and survey are traditional pedological topics. These topics require astute field assessment of soil http://soils.ifas.ufl.edu morphology and composition. However, remote sensing technology, digitally-linked geographic data, and powerful computer-driven geographic information systems (GIS) have been exploited in recent years to extend pedological applications beyond EDITORS: traditional field-based reconnaissance. These tools have led to landscape modeling and development of digital soil mapping techniques. Susan Curry [email protected] Florida State soil is “Myakka” fine sand, a flatwood soil, classified as Spodosols. Myakka is pronounced ‘My-yak-ah’ - a Native American word for Big Waters. Reflecting Dr. Vimala Nair our department’s mission, we named our newsletter as “Myakka”. For details about [email protected] Myakka fine sand see: http://soils.ifas.ufl.edu/docs/pdf/Myakka-Fl-State-Soil.pdf Michael Sisk [email protected] This newsletter highlights Florida pedological activities of the Soil and Water Science Department (SWSD) and USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS). -

Richard Sullivan, President

Participating Organizations Alliance for a Living Ocean American Littoral Society Arthur Kill Coalition Clean Ocean Action www.CleanOceanAction.org Asbury Park Fishing Club Bayberry Garden Club Bayshore Regional Watershed Council Bayshore Saltwater Flyrodders Belford Seafood Co-op Main Office Institute of Coastal Education Belmar Fishing Club Beneath The Sea 18 Hartshorne Drive 3419 Pacific Avenue Bergen Save the Watershed Action Network P.O. Box 505, Sandy Hook P.O. Box 1098 Berkeley Shores Homeowners Civic Association Wildwood, NJ 08260-7098 Cape May Environmental Commission Highlands, NJ 07732-0505 Central Jersey Anglers Voice: 732-872-0111 Voice: 609-729-9262 Citizens Conservation Council of Ocean County Fax: 732-872-8041 Fax: 609-729-1091 Clean Air Campaign, NY Ocean Advocacy [email protected] Coalition Against Toxics [email protected] Coalition for Peace & Justice/Unplug Salem Since 1984 Coast Alliance Coastal Jersey Parrot Head Club Communication Workers of America, Local 1034 Concerned Businesses of COA Concerned Citizens of Bensonhurst Concerned Citizens of COA Concerned Citizens of Montauk Eastern Monmouth Chamber of Commerce Fisher’s Island Conservancy Fisheries Defense Fund May 31, 2006 Fishermen’s Dock Cooperative, Pt. Pleasant Friends of Island Beach State Park Friends of Liberty State Park, NJ Friends of the Boardwalk, NY Garden Club of Englewood Edward Bonner Garden Club of Fair Haven Garden Club of Long Beach Island Garden Club of Middletown US Army Corps of Engineers Garden Club of Morristown -

Afm 305 Limnology 2

COURSE GUIDE AFM 305 LIMNOLOGY Course Team Dr. Flora E. Olaifa (Course Writer) – Dept. of Aquaculture and Fisheries Management, University of Ibadan Dr. E. O. Ajao & Mrs. R. M. Bashir (Course Editors) – NOUN Prof. G. E. Jokthan (Programme Leader) – NOUN Mrs. R. M. Bashir (Course Coordinator) – NOUN NATIONAL OPEN UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA ACC 318 COURSE GUIDE National Open University of Nigeria Headquarters University Village Plot 91, Cadastral Zone, Nnamdi Azikiwe Express way Jabi, Abuja Lagos Office 14/16 Ahmadu Bello Way Victoria Island, Lagos e-mail: [email protected] website: www.nou.edu.ng Published by National Open University of Nigeria Printed 2016 ISBN: 978-058-590-X All Rights Reserved ii AFM 305 COURSE GUIDE CONTENTS PAGE What you will Learn in this Course...................................... iv Course Aim..................................................................... ......... v Course Objectives................................................................. v Course Description.............................................................. vi Course Materials................................................................. vii Study Units......................................................................... viii Set Textbooks..................................................................... ix Assignment File…………………………………………….. ix Course Assessment............................................................. ix Tutor-Marked Assignment................................................. x Final Examination and Grading........................................ -

Abandoned Channels (Avulsions)

Musselshell BMPs 1 Abandoned Channels (Avulsions) Applicability The following Best Management Practices (“BMPs”) summarize several recommended approaches to managing abandoned channels within the Musselshell River stream corridor. The information is based upon the on- site evaluation of floodplain features and discussions with producers, and is intended for producers and residents who are living or farming in areas where abandoned channel segments exist. Description Perhaps the most dramatic 2011 flood Figure 1. 2011 avulsion, Musselshell River. impact on the Musselshell River was the number of avulsions that occurred over the period of a few weeks. An “avulsion” is the rapid formation of a new river channel across the floodplain that captures the flow of the main channel thread. River avulsions typically occur when rivers find a relatively steep, short flow path across their floodplain. When floodwaters re- enter the river over a steep bank, they form headcuts that migrate upvalley, creating a new channel, causing intense erosion, and sending a sediment slug downswtream. If the new channel completely develops, it can capture the main thread, resulting in a successful avulsion. If floodwaters recede before the new channel is completely formed, or if the floodplain is resistant to erosion, the avulsion may fail. From near Harlowton to Fort Peck Reservoir, 59 avulsions occurred on the Musselshell in the spring of 2011, abandoning a total of 39 miles of channel. The abandoned channel segments range in length from 280 feet to almost three miles. One of the reasons there were so many avulsions on the Figure 2. Upstream-migrating headcuts showing Musselshell River in 2011 is because the floodwaters stayed creation of avulsion path, 2011. -

A Primer on Limnology, Second Edition

BIOLOGICAL PHYSICAL lake zones formation food webs variability primary producers light chlorophyll density stratification algal succession watersheds consumers and decomposers CHEMICAL general lake chemistry trophic status eutrophication dissolved oxygen nutrients ecoregions biological differences The following overview is taken from LAKE ECOLOGY OVERVIEW (Chapter 1, Horne, A.J. and C.R. Goldman. 1994. Limnology. 2nd edition. McGraw-Hill Co., New York, New York, USA.) Limnology is the study of fresh or saline waters contained within continental boundaries. Limnology and the closely related science of oceanography together cover all aquatic ecosystems. Although many limnologists are freshwater ecologists, physical, chemical, and engineering limnologists all participate in this branch of science. Limnology covers lakes, ponds, reservoirs, streams, rivers, wetlands, and estuaries, while oceanography covers the open sea. Limnology evolved into a distinct science only in the past two centuries, when improvements in microscopes, the invention of the silk plankton net, and improvements in the thermometer combined to show that lakes are complex ecological systems with distinct structures. Today, limnology plays a major role in water use and distribution as well as in wildlife habitat protection. Limnologists work on lake and reservoir management, water pollution control, and stream and river protection, artificial wetland construction, and fish and wildlife enhancement. An important goal of education in limnology is to increase the number of people who, although not full-time limnologists, can understand and apply its general concepts to a broad range of related disciplines. A primary goal of Water on the Web is to use these beautiful aquatic ecosystems to assist in the teaching of core physical, chemical, biological, and mathematical principles, as well as modern computer technology, while also improving our students' general understanding of water - the most fundamental substance necessary for sustaining life on our planet. -

The Origin and Paleoclimatic Significance of Carbonate Sand Dunes Deposited on the California Channel Islands During the Last Glacial Period

Pages 3–14 in Damiani, C.C. and D.K. Garcelon (eds.). 2009. Proceedings of 3 the 7th California Islands Symposium. Institute for Wildlife Studies, Arcata, CA. THE ORIGIN AND PALEOCLIMATIC SIGNIFICANCE OF CARBONATE SAND DUNES DEPOSITED ON THE CALIFORNIA CHANNEL ISLANDS DURING THE LAST GLACIAL PERIOD DANIEL R. MUHS,1 GARY SKIPP,1 R. RANDALL SCHUMANN,1 DONALD L. JOHNSON,2 JOHN P. MCGEEHIN,3 JOSSH BEANN,1 JOSHUA FREEMAN,1 TIMOTHY A. PEARCE,4 1 AND ZACHARY MUHS ROWLAND 1U.S. Geological Survey, MS 980, Box 25046, Federal Center, Denver, CO 80225; [email protected] 2Department of Geography, University of Illinois, Urbana, IL 61801 3U.S. Geological Survey, MS 926A, National Center, Reston, VA 20192 4Section of Mollusks, Carnegie Museum of Natural History, 4400 Forbes Ave., Pittsburgh, PA 15213 Abstract—Most coastal sand dunes, including those on mainland California, have a mineralogy dominated by silicates (quartz and feldspar), delivered to beach sources from rivers. However, carbonate minerals (aragonite and calcite) from marine invertebrates dominate dunes on many tropical and subtropical islands. The Channel Islands of California are the northernmost localities in North America where carbonate-rich coastal dunes occur. Unlike the mainland, a lack of major river inputs of silicates to the island shelves and beaches keeps the carbonate mineral content high. The resulting distinctive white dunes are extensive on San Miguel, Santa Rosa, San Nicolas, and San Clemente islands. Beaches have limited extent on all four of these islands at present, and some dunes abut rocky shores with no sand sources at all. Thus, the origin of many of the dunes is related to the lowering of sea level to ~120 m below present during the last glacial period (~25,000 to 10,000 years ago), when broad insular shelves were subaerially exposed. -

River Channel Bars and Dunes- Theory of Kinematic Waves

River Channel Bars and Dunes- Theory of Kinematic Waves GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 422-L River Channel Bars and Dunes- Theory of Kinematic Waves By WALTER B. LANGBEIN and LUNA B. LEOPOLD PHYSIOGRAPHIC AND HYDRAULIC STUDIES OF RIVERS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 422-L UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1968 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY William T. Pecora, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price 20 cents (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Page Abstract_________________________________________ LI Effect of rock spacing on rock movement in an ephemeral Introduction.______________________________________ 1 stream._________________________________________ L9 Flux-concentration relations________________________ 2 Waves in bed form________________________________ 12 Relation of particle speed to spacing a flume experi- General features________________________________ 12 ment______-_____-____-____-_-____________--____. 4 Kinematic properties_._______-._________________ 15 Transport of sand in pipes and flumes_________________ 5 Gravel bars____________________________________ 17 Flux-concentration curve for pipes________________ 6 Summary__________________________________________ 19 Flume transport of sand_________________________ 7 References________________.______________________ 19 ILLUSTRATIONS Page FIGURE 1. Flux-concentration curve for traffic___________________________________________________-_-_-__-___- -

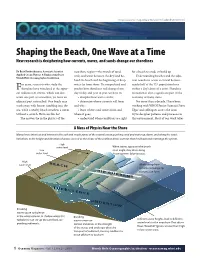

Shaping the Beach, One Wave at a Time New Research Is Deciphering How Currents, Waves, and Sands Change Our Shorelines

http://oceanusmag.whoi.edu/v43n1/raubenheimer.html Shaping the Beach, One Wave at a Time New research is deciphering how currents, waves, and sands change our shorelines By Britt Raubenheimer, Associate Scientist nearshore region—the stretch of sand, for a beach to erode or build up. Applied Ocean Physics & Engineering Dept. rock, and water between the dry land be- Understanding beaches and the adja- Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution hind the beach and the beginning of deep cent nearshore ocean is critical because or years, scientists who study the water far from shore. To comprehend and nearly half of the U.S. population lives Fshoreline have wondered at the appar- predict how shorelines will change from within a day’s drive of a coast. Shoreline ent fickleness of storms, which can dev- day to day and year to year, we have to: recreation is also a significant part of the astate one part of a coastline, yet leave an • decipher how waves evolve; economy of many states. adjacent part untouched. One beach may • determine where currents will form For more than a decade, I have been wash away, with houses tumbling into the and why; working with WHOI Senior Scientist Steve sea, while a nearby beach weathers a storm • learn where sand comes from and Elgar and colleagues across the coun- without a scratch. How can this be? where it goes; try to decipher patterns and processes in The answers lie in the physics of the • understand when conditions are right this environment. Most of our work takes A Mess of Physics Near the Shore Many forces intersect and interact in the surf and swash zones of the coastal ocean, pushing sand and water up, down, and along the coast.