Workers Buyout: Why Employee-Owned Enterprises Are More Resilient Than Corporate Business in Time of Economic and Financial Crisis?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Italy's Atlanticism Between Foreign and Internal

UNISCI Discussion Papers, Nº 25 (January / Enero 2011) ISSN 1696-2206 ITALY’S ATLANTICISM BETWEEN FOREIGN AND INTERNAL POLITICS Massimo de Leonardis 1 Catholic University of the Sacred Heart Abstract: In spite of being a defeated country in the Second World War, Italy was a founding member of the Atlantic Alliance, because the USA highly valued her strategic importance and wished to assure her political stability. After 1955, Italy tried to advocate the Alliance’s role in the Near East and in Mediterranean Africa. The Suez crisis offered Italy the opportunity to forge closer ties with Washington at the same time appearing progressive and friendly to the Arabs in the Mediterranean, where she tried to be a protagonist vis a vis the so called neo- Atlanticism. This link with Washington was also instrumental to neutralize General De Gaulle’s ambitions of an Anglo-French-American directorate. The main issues of Italy’s Atlantic policy in the first years of “centre-left” coalitions, between 1962 and 1968, were the removal of the Jupiter missiles from Italy as a result of the Cuban missile crisis, French policy towards NATO and the EEC, Multilateral [nuclear] Force [MLF] and the revision of the Alliance’ strategy from “massive retaliation” to “flexible response”. On all these issues the Italian government was consonant with the United States. After the period of the late Sixties and Seventies when political instability, terrorism and high inflation undermined the Italian role in international relations, the decision in 1979 to accept the Euromissiles was a landmark in the history of Italian participation to NATO. -

On the Streets of San Francisco for Justice PAGE 8

THE VOICE OF THE UNION April b May 2016 California Volume 69, Number 4 CALIFORNIA TeacherFEDERATION OF TEACHERS, AFT, AFL-CIO STRIKE! On the streets of San Francisco for justice PAGE 8 Extend benefits Vote June 7! A century of of Prop. 30 Primary Election workers’ rights Fall ballot measure opportunity Kamala Harris for U.S. Senate Snapshot: 100 years of the AFT PAGE 3 PAGE 5 PAGE 7 California In this issue All-Union News 03 Community College 14 Teacher Pre-K/K-12 12 University 15 Classified 13 Local Wire 16 UpFront Joshua Pechthalt, CFT President Election 2016: Americans have shown they that are ready for populist change here is a lot at stake in this com- But we must not confuse our elec- message calling out the irresponsibil- Ting November election. Not only toral work with our community build- ity of corporate America. If we build will we elect a president and therefore ing work. The social movements that a real progressive movement in this shape the Supreme Court for years to emerged in the 1930s and 1960s weren’t country, we could attract many of the Ultimately, our job come, but we also have a key U.S. sen- tied to mainstream electoral efforts. Trump supporters. ate race, a vital state ballot measure to Rather, they shaped them and gave In California, we have changed is to build the social extend Proposition 30, and important rise to new initiatives that changed the the political narrative by recharging state and local legislative races. political landscape. Ultimately, our job the labor movement, building ties movements that keep While I have been and continue is to build the social movements that to community organizations, and elected leaders to be a Bernie supporter, I believe keep elected leaders moving in a more expanding the electorate. -

50 YEARS of EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT HISTORY and Subjugated

European Parliament – 50th birthday QA-70-07-089-EN-C series 1958–2008 Th ere is hardly a political system in the modern world that does not have a parliamentary assembly in its institutional ‘toolkit’. Even autocratic or totalitarian BUILDING PARLIAMENT: systems have found a way of creating the illusion of popular expression, albeit tamed 50 YEARS OF EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT HISTORY and subjugated. Th e parliamentary institution is not in itself a suffi cient condition for granting a democratic licence. Yet the existence of a parliament is a necessary condition of what 1958–2008 we have defi ned since the English, American and French Revolutions as ‘democracy’. Since the start of European integration, the history of the European Parliament has fallen between these two extremes. Europe was not initially created with democracy in mind. Yet Europe today is realistic only if it espouses the canons of democracy. In other words, political realism in our era means building a new utopia, that of a supranational or post-national democracy, while for two centuries the DNA of democracy has been its realisation within the nation-state. Yves Mény President of the European University Institute, Florence BUILDING PARLIAMENT: BUILDING 50 YEARS OF EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT HISTORY PARLIAMENT EUROPEAN OF YEARS 50 ISBN 978-92-823-2368-7 European Parliament – 50th birthday series Price in Luxembourg (excluding VAT): EUR 25 BUILDING PARLIAMENT: 50 YEARS OF EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT HISTORY 1958–2008 This work was produced by the European University Institute, Florence, under the direction of Yves Mény, for the European Parliament. Contributors: Introduction, Jean-Marie Palayret; Part One, Luciano Bardi, Nabli Beligh, Cristina Sio Lopez and Olivier Costa (coordinator); Part Two, Pierre Roca, Ann Rasmussen and Paolo Ponzano (coordinator); Part Three, Florence Benoît-Rohmer; Conclusions, Yves Mény. -

Minorities Formation in Italy

Minorities Formation in Italy GIOVANNA CAMPANI Minorities Formation in Italy Introduction For historical reasons Italy has always been characterized as a linguistically and culturally fragmented society. Italy became a unifi ed nation-state in 1860 after having been divided, for centuries, into small regional states and having been dominated, in successive times, by different European countries (France, Spain, and Austria). As a result, two phenomena have marked and still mark the country: - the existence of important regional and local differences (from the cultural, but also economic and political point of view); the main difference is represented by the North-South divide (the question of the Mezzogiorno) that has strongly in- fl uenced Italian history and is still highly present in political debates; and - the presence of numerous “linguistic” minorities (around fi ve percent of the Italian population) that are very different from each other. In Italy, one commonly speaks of linguistic minorities: regional and local differences are expressed by the variety of languages and dialects that are still spoken in Italy. The term “ethnic” is scarcely used in Italy, even if it has been employed to defi ne minorities together with the term “tribes” (see GEO special issue “the tribes of Italy”). When minorities speak of themselves, they speak in terms of populations, peo- ples, languages, and cultures. The greatest concentration of minorities is in border areas in the northeast and northwest that have been at the centre of wars and controversies during the 20th century. Other minorities settled on the two main islands (where they can sometimes constitute a ma- 1 Giovanna Campani jority, such as the Sardinians). -

Economic Development and Industrial Relations in a Small-Firm Economy: the Experience of Metalworkers in Emilia- Romagna, Italy

Upjohn Institute Press Economic Development and Industrial Relations in a Small-Firm Economy: The Experience of Metalworkers in Emilia- Romagna, Italy Bruce Herman Garment Industry Development Corporation Chapter 2 (pp. 19-40) in: Restructuring and Emerging Patterns of Industrial Relations Stephen R. Sleigh, ed. Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, 1993 DOI: 10.17848/9780880995566.ch2 Copyright ©1993. W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. All rights reserved. Economic Development and Industrial Relations in a Small-Firm Economy The Experience of Metalworkers in Emilia-Romagna, Italy Bruce Herman Garment Industry Development Corporation One example often referred to in discussions of successful eco nomic restructuring is the "Third Italy," particularly the Emilia- Romagna region of north-central Italy. And yet in the growing litera ture on Emilia-Romagna there is often little mention of the role of industrial relations in this predominantly small-firm economy. This chapter seeks to explain the history and results of a proactive collective bargaining strategy developed by the Federazione Impiegati Operai Metallurgici (FIOM), the metal-mechanical union affiliated with the Confederazione Generale Italiana del Lavoro (CGIL), in the context of the successful industrial restructuring of the Emilian economy. The FIOM, with almost 70,000 members in the region (Catholic and Republican affiliates have 16,000 members), in an industry sector with a 55 percent unionization rate, has used its strength to pursue a proac tive collective bargaining strategy designed to increase worker partici pation and control.1 Leveraging needed organizational change within the firm to gain greater autonomy and an expanded role in the restruc turing process, the FIOM is trying to "regain" control of work layout and job design. -

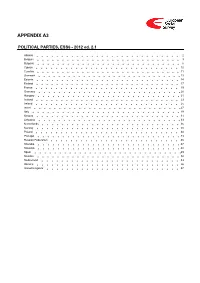

ESS6 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS6 - 2012 ed. 2.1 Albania 2 Belgium 3 Bulgaria 6 Cyprus 10 Czechia 11 Denmark 13 Estonia 14 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Israel 27 Italy 29 Kosovo 31 Lithuania 33 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 43 Russian Federation 45 Slovakia 47 Slovenia 48 Spain 49 Sweden 52 Switzerland 53 Ukraine 56 United Kingdom 57 Albania 1. Political parties Language used in data file: Albanian Year of last election: 2009 Official party names, English 1. Partia Socialiste e Shqipërisë (PS) - The Socialist Party of Albania - 40,85 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Partia Demokratike e Shqipërisë (PD) - The Democratic Party of Albania - 40,18 % election: 3. Lëvizja Socialiste për Integrim (LSI) - The Socialist Movement for Integration - 4,85 % 4. Partia Republikane e Shqipërisë (PR) - The Republican Party of Albania - 2,11 % 5. Partia Socialdemokrate e Shqipërisë (PSD) - The Social Democratic Party of Albania - 1,76 % 6. Partia Drejtësi, Integrim dhe Unitet (PDIU) - The Party for Justice, Integration and Unity - 0,95 % 7. Partia Bashkimi për të Drejtat e Njeriut (PBDNJ) - The Unity for Human Rights Party - 1,19 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Socialist Party of Albania (Albanian: Partia Socialiste e Shqipërisë), is a social- above democratic political party in Albania; it is the leading opposition party in Albania. It seated 66 MPs in the 2009 Albanian parliament (out of a total of 140). It achieved power in 1997 after a political crisis and governmental realignment. In the 2001 General Election it secured 73 seats in the Parliament, which enabled it to form the Government. -

Wp3 - Task 3.2

SWIRL – Slash Workers and Industrial ReLations PROJECT DG Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion “Improving expertise in the field of industrial relations - VP/2018/004” WP3 - TASK 3.2 DETECTION AND ANALYSIS OF RELEVANT PRACTICES IN INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS: CASE STUDIES’ REPORT University of Cádiz – UCA Team May 15th, 2021 CONTENTS 1. Introduction 3 2. SWIRL case studies: a brief presentation on common patterns 4 3. Bulgaria 14 3.1. CITUB app 15 3.2. Professional and freelance services FB group 23 4. France 31 4.1. Coopcycle 32 4.2. HappyDev 42 4.3. Les Sons Fédérés 51 5. Germany 66 5.1. IG Metall Ombudstelle (Mediation Office) for Fair 67 Crowd Work 5.2. Liefern am Limit 76 5.3. Smart De 96 6. Italy 96 6.1. Consegne Etiche 97 6.2. Doc Servizi 111 6.3. Fairbnb 125 6.4. Humus 137 7. Spain 144 7.1. Riders x Derechos 145 7.2. Smart Ibérica 169 7.3. Tu Respuesta Sindical ya (TRS)- UGT 188 8. Final remarks 210 9. Annex 1. Case-study content structure 212 2 1. INTRODUCTION One of the SWIRL project aims is to identify and study the most relevant practices of protection and representation of contingent/slash workers, analysing in depth their needs and aspirations, if and how these needs and aspirations are represented and promoted, and barriers found. Within WP3, Task 3.2 centres on the detection and analysis of relevant practices in industrial relations in order to ascertain and assess their level of effectiveness and impact. In order to accomplish this goal, each of the five countries participating in the project had to select and develop three case studies. -

Europe's Bumper Year of Elections

2017: Europe’s Bumper Year of Elections Published by European University Institute (EUI) Via dei Roccettini 9, I-50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy First Published 2018 ISBN:978-92-9084-715-1 doi:10.2870/66375 © European University Institute, 2018 Editorial matter and selection © Brigid Laffan, Lorenzo Cicchi, 2018 Chapters © authors individually 2018 This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Any additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the European Governance and Pol- itics Programme. If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the year and the publisher. Views expressed in this publication reflect the opinion of individual authors and not those of the European University Institute. 2017: Europe’s Bumper Year of Elections EDITED BY Brigid Laffan Lorenzo Cicchi AUTHORS Rachid Azrout Anita Bodlos Endre Borbáth Enrico Calossi Lorenzo Cicchi Marc Debus James Dennison Martin Haselmayer Laurenz Ennser-Jedenastik Haylee Kelsall Romain Lachat Thomas M. Meyer Elie Michel Wolfgang C. Müller Ferdinand Müller-Rommel Thomas Poguntke Richard Rose Tobias Rüttenauer Johannes Schmitt Julia Schulte-Cloos Joost van Spanje Bryan Synnott Catherine E. de Vries European University Institute, Florence, Italy Table of Contents Acknowledgements viii Preface ix The Contributors xiii Part 1 – Thematic and Comparative Chapters The Crisis, Party System Change, and the Growth of Populism 1 Thomas Poguntke & Johannes -

8. Kravchuk to the Orange Revolution

After Independence: Making and Protecting the Nation in Postcolonial and Postcommunist States Lowell W. Barrington, Editor http://www.press.umich.edu/titleDetailDesc.do?id=126246 The University of Michigan Press 8. Kravchuk to the Orange Revolution The Victory of Civic Nationalism in Post-Soviet Ukraine TARAS KUZIO Ukraine’s 2004 presidential election and Orange Revolution was facilitated by the role of civic nationalism. The inability to mobilize civic nationalism in suf‹cient quantity in 1991–92 permitted the election of sov- ereign Communist Leonid Kravchuk and later centrist Leonid Kuchma. The growth of a civic nationalist Ukrainian identity from 1992–2004 trans- formed the political landscape, permitting Viktor Yushchenko to be elected president.1 Civic and ethnic nationalists in Ukraine can be differentiated fairly effectively based on their views on two issues, corresponding to the idea proposed by Lowell Barrington in this volume’s introductory chapter that nationalism involves both membership boundaries and territorial bound- aries. First, they have different de‹nitions of the state, as either inclusive (civic) or exclusive (ethnic). Second, they either support Ukraine’s inher- ited borders (civic nationalists) or harbor a desire to change them (ethnic Ukrainian, Russian nationalists, and Sovietophiles). This chapter is divided into two sections, which deal separately with ethnic and civic nationalism before and after independence. Prior to independence, ethnic nationalists grouped within the Interpar- liamentary Assembly (IPA) demanded independence from the moment of its arrival on Ukraine’s political scene in 1989. After Ukraine became an independent state, the IPA transformed itself into the Ukrainian National Assembly (UNA). As an ethnic nationalist movement, it was joined by sev- eral new parties.2 Civic nationalism only appeared as a phenomenon in 1990–91, although the Ukrainian Popular Movement for Restructuring 187 After Independence: Making and Protecting the Nation in Postcolonial and Postcommunist States Lowell W. -

Economic Restructuring and Emerging Patterns of Industrial Relations

Upjohn Press Upjohn Research home page 1-1-1993 Economic Restructuring and Emerging Patterns of Industrial Relations Stephen R. Sleigh City University of New York Follow this and additional works at: https://research.upjohn.org/up_press Part of the Labor and Employment Law Commons, Labor Economics Commons, and the Labor Relations Commons Citation Sleigh, Stephen R., ed. 1993. Economic Restructuring and Emerging Patterns of Industrial Relations. Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. https://doi.org/10.17848/ 9780880995566 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License. This title is brought to you by the Upjohn Institute. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Economic AND Relations COM^Stephen m • R. Sleigh^^m ' • • Economic Restructuring AND Emerging Patterns OF Industrial Relations Stephen R. Sleigh Editor 1993 W.E. UPJOHN INSTITUTE for Employment Research Kalamazoo, Michigan 49007 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Economic restructuring and emerging patterns of industrial relations / Stephen R. Sleigh, editor, p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-88099-131-3 (pbk.) — ISBN 0-88099-132-1 (cloth) 1. Industrial relations—United States—Case studies. 2. Industrial relations—Europe—Case studies. I. Sleigh, Stephen R. HD8072.5.E37 1992 331—dc20 92-36997 CIP Copyright © 1993 W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research 300 S. Westnedge Avenue Kalamazoo, Michigan 49007 THE INSTITUTE, a nonprofit research organization, was established on July 1, 1945. It is an activity of the W.E. Upjohn Unemployment Trustee Corporation, which was formed in 1932 to administer a fund set aside by the late Dr. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI film*; the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Z eeb Road.Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346USA 313/761-4700 800:521-0600 Order Number 9517060 Politics of labor reform in post-transition Brazil: Possibilities and limits of the labor reform in a conservative transition Oh, Samgyo, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1994 UMI 300 N. -

No. 2, April-May, 1997

April-May 1997 No. 2 $2 rnationalist Australia $2.50, Brazil R$2, Britai~£t5o, No Popular Front, Build a Trotskyist Party. .. 16 Canada $2.50, France 10F, Germany0M'3t Italy L3.000, Japan ¥200, M~xicql~. Ex-Far Left in the Reformist Swamp . ... 21 South Africa R5 , · 2 The Internationalist April-May 1997 Port Strike Against Union-Busting in Brazil In the early morning hours of April 15, some 500 heavily armed shock troops of Brazil's military and federal police stormed the port of Santos, near Sao Paulo. Their purpose was to break a work action by the water front unions in defense of the union hiring hall against attempts to break it by the privatized Sao Paulo steel company. Following the police invasion 2,500 workers occupied the port area. A leaflet on the port strike by the Liga Quarta-Intemacionalista do Brasil (LQB) together with an April 20 supplement to The Internationalist are available our web site (www.intemationalist.org), or write for a copy to the Internationalist Group, Box 3321, Church Street Station, New York, NY 10008, U.S.A. Order Now! U.S. $2 Order from/make checks payable to: Mundial Publications, Box 3321, Church Street Station, New York, NY 10008, U.S.A. Visit the Internationalist Group on the Internet Internationalist A Journal of Revolutionary Marxism Web site address: for the Reforging of the Fourth International http://www.internationalist.org Publication of the Internationalist Group Now available on our site are: • Founding Statement of the Internation- EDITORIAL BOARD: Jan Norden (editor), Abram Negrete, alist Group Buenaventura Santamaria, Marjorie Salzburg, Socorro Valero.