Katherine Kirkwood Thesis (PDF 1MB)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Student Handbook Have Been Designed to Help Students Make the Best of Their Educational Experience at FLS

FREDERICKTOWN L O C A L S C H O O L S 2021-2022 STUDENT/PARENT HANDBOOK Every day, everyone learning and adapting to excel in a changing world 1 FORWARD Welcome to Fredericktown Local Schools! We have been planning for an exciting year and are eager to get started. The Student Planner and Parent-Student Handbook have been designed to help students make the best of their educational experience at FLS. They provide the framework for conducting the business of education at Fredericktown Local Schools. The vision, mission, and belief statements on the back cover outline the high ideals which each of us strives for daily. They embrace the expectations of the district and community, as well as declare the core values of the FLS staff. Inside the handbook, various policies and procedures are detailed to assist students and parent(s) or guardian(s) with issues ranging from academic support and attendance procedures to grade cards and progress reports. Equally important is the Student Conduct Code, which details the standards for student behavior. This handbook, however, is not a complete summary of all of the policies, practices and procedures that apply to students during their enrollment in the District. If a situation occurs where you are unsure what may be expected, please speak to a school official. If there are any conflicts between the provisions of this handbook and Board Policy, the requirements of the Board-adopted Policy will be applied. Upon receipt, each student and parent is responsible for the information contained in the handbook, including the Student Conduct Code. -

Adjudicator and Finalists Announced

The only way to fi nd out what’s going on! Serving the Hunter for over 20 years with a readership of over 4,000 weekly! Thursday 15th February, 2018 Missed an issue? www.huntervalleyprinting.com.au/Pages/Entertainer.php FREE ENTRY 8 TAB RACES See inside BUSINESS RACE DAY FEB 23 Driving the Hunter 2018 for 60 years! TV Guide FRIDAY 23rd OF FEBRUARY ARE YOU LOOKING FOR MORE NETWORKING? MORE EXPOSURE? Adjudicator and fi nalists 434 Bunnan Road Scone NSW - 02.6545.1607 - www.sconeraceclub.com.au announced Muswellbrook Regional Arts Centre WWININ ! has announced the fi nalists of the 45th Muswellbrook Art Prize along with this year’s a double pass to Majestic Cinemas. adjudicator - Tracy Cooper-Lavery, Gallery www.facebook.com/EntertainerPublication See page 2 for details Director, Gold Coast City Gallery. Finalists of the 45th Muswellbrook Art Prize will WHEN compete for a total prize pool of $71,000, with SUNDAY 18 MARCH 2018 26 works selected for the $50,000. Painting 10AM - 3PM 18 Prize, 19 works for the $10,000 Works on MAR WHERE Paper Prize and 12 works for the $10,000 MICHAEL REID MURRURUNDI Ceramics Prize. LITTLE STREET MURRURUNDI Winners of the Art Prize will be announced at the opening night at 6pm Saturday 10 March Free activities for the little people Espresso Coffee & Catering 2018. A $1,000 People’s Choice Prize can also QUALITY, HANDMADE, Live Entertainment be voted for during the course of the exhibition. LOCALISH GOODS AND Cooking with Local Produce Demonstration Series of Homegrown + Visit the MRAC website for the full list of FRESH PRODUCE MARKET Handmade Mini Workshops fi nalists. -

A Step Closer to Electrical Self Sufficiency

Saturday, June 12, 2021 Sunday: 15° Monday: 18° Tuesday: 17° No. 32,865 BROKEN HILL TODAY: 17° $2.50 Vale, Indian Club Netball Grandand Ray Cook Spinner Finals PagePage 2 PagePage 8 BackBack pagepage Debutantes to fi nally get their Ball By Emily Ferguson Th e ball will be the fi rst of its kind South Football Club Debutante Ball 2021 Debutantes and Squires, (From since 2019, with COVID halting all left) Ella McLeod and Marcus Purcell, Paige Fargher and Adam Slattery, social events and gatherings - Debutante Halle McNamara and Joel Van Kemenade, Karleigh-Anne Leiper and Mason Next Friday marks the annual Balls included. Th e SFC Debutante Ball McCully, Shaina Burns and Aiden Slattery, Elkie Philp and Lucas Stacey, South Football Club Debutante will happen on the third scheduled Mackenzie Tonkin and Jet Johnson, Jessie-Kay Hendry and Kaleb Philp, Ella Ball, where nine lovely local young date, aft er being postponed twice due Knowles and Kade Pettitt. PICTURE: Emily Ferguson. ladies will make their debut. to COVID restrictions. Continued on page 4 A step closer to electrical self suffi ciency By Neil Pigot In 2020, Hydrostor’s 200 MW, 8 hour or inside a purpose-built cavern where hydro- be up to $560 million, with the vast major- 1600 MWh storage system was selected by static compensation is used to maintain the ity of construction expenditures occurring NSW’s transmission network service pro- system at a constant pressure, preserving within the community of Broken Hill. Broken Hill came a step closer to vider, Transgrid, as the preferred option for the heat energy for use later in the cycle. -

Guidelines on Communications Strategies for the Transition from Analogue to Digital Terrestrial Broadcasting

2014-2017 Guidelines ITU-D Study Group 1 Question 8/1 International Telecommunication Union Telecommunication Development Bureau Guidelines on Place des Nations CH-1211 Geneva 20 Communications Switzerland www.itu.int Strategies for the Transition from Analogue to Digital Terrestrial Broadcasting 6th Study Period 2014-2017 EXAMINATION OF STRATEGIES AND METHODS OF MIGRATION FROM ANALOGUE TO DIGITAL TERRESTRIAL BROADCASTING AND IMPLEMENTATION OF NEW SERVICES OF NEW AND IMPLEMENTATION BROADCASTING TERRESTRIAL DIGITAL TO ANALOGUE FROM AND METHODS OF MIGRATION OF STRATEGIES EXAMINATION ISBN 978-92-61-24801-7 QUESTION 8/1: QUESTION 9 7 8 9 2 6 1 2 4 8 0 1 7 Printed in Switzerland Geneva, 2017 07/2017 International Telecommunication Union (ITU) Telecommunication Development Bureau (BDT) Office of the Director Place des Nations CH-1211 Geneva 20 – Switzerland Email: [email protected] Tel.: +41 22 730 5035/5435 Fax: +41 22 730 5484 Deputy to the Director and Infrastructure Enabling Innovation and Partnership Project Support and Knowledge Director,Administration and Environmnent and Department (IP) Management Department (PKM) Operations Coordination e-Applications Department (IEE) Department (DDR) Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Tel.: +41 22 730 5784 Tel.: +41 22 730 5421 Tel.: +41 22 730 5900 Tel.: +41 22 730 5447 Fax: +41 22 730 5484 Fax: +41 22 730 5484 Fax: +41 22 730 5484 Fax: +41 22 730 5484 Africa Ethiopia Cameroon Senegal Zimbabwe International Telecommunication Union internationale des Union internationale des International Telecommunication Union (ITU) télécommunications (UIT) télécommunications (UIT) Union (ITU) Regional Office Bureau de zone Bureau de zone Area Office P.O. -

Andy Allen Was Just One Exam Short of Becoming a Fully-Qualified Electrician When He Entered Masterchef Australia As a Dare from His Mates

Andy Allen was just one exam short of becoming a fully-qualified electrician when he entered Masterchef Australia as a dare from his mates. Four years later, he hasn’t looked back. The boy from Maitland had a culinary baptism of fire during the series, eventually walking away with the title of Masterchef’s youngest ever winner. Andy soon packed his bags and moved to Sydney, and began working under the guidance of Darren Robertson and Mark LaBrooy at Bronte’s Three Blue Ducks. In 2013 Andy and his mate Ben Milbourne (Masterchef 2012 alumni) made good on their promise of visiting Mexico together, and it’s here that they connected with a Producer and began filming their culinary travels, in what became web series Andy & Ben Do Mexico. From here, things continued to remain flatout in the kitchen for Andy, but the curious chef had a foodie travel itch he couldn’t ignore. Next up, the boys co-produced the Spain and Portugal leg of what became their first television series Andy & Ben Eat The World, which received national broadcast in 2015. In 2016 Andy hit the road closer to home, with Andy & Ben Eat Australia. Andy is an author, a blogger (he won Pedestrian’s 10th Annual Food Blogger of the Year in 2015). He has appeared on The Today Show America, worked with numerous charities and continues to make people laugh and learn new things about food by sharing his passion for learning. In 2016, Andy added ‘restauranter’ to his CV, going into business as co-owner and chef of the Three Blue Ducks, Rosebery. -

27/10/2019 - 02/11/2019) 18:00 - 23:59 Total Individuals - Including Guests

Consolidated National Subscription TV Share and Reach National Share and Reach Report - Subscription TV Homes only Week 44 2019 (27/10/2019 - 02/11/2019) 18:00 - 23:59 Total Individuals - Including Guests Channel Share Of Viewing Reach Weekly 000's % TOTAL PEOPLE ABC 5.4 1678 ABCKIDS/COMEDY 1.0 766 ABC ME 0.3 284 ABC NEWS 0.4 372 Seven + AFFILIATES 12.5 2595 7TWO + AFFILIATES 1.0 541 7mate + AFFILIATES 1.5 833 7flix + AFFILIATES 0.6 467 7food network + AFFILIATES 0.1 117 Nine + AFFILIATES* 14.8 3018 GO + AFFILIATES* 1.9 1101 Gem + AFFILIATES* 1.1 534 9Life + AFFILIATES* 0.6 319 10 + AFFILIATES* 7.4 2525 10 Bold + AFFILIATES* 1.0 610 10 Peach + AFFILIATES* 1.0 661 Sky News on WIN + AFFILIATES* 0.2 167 SBS 2.3 1303 SBS VICELAND 0.6 604 SBS Food 0.5 412 NITV 0.1 199 SBS World Movies 0.3 357 111 0.6 513 111 +2 0.3 242 13TH STREET 0.6 283 13TH STREET+2 0.2 128 [V] 0.2 191 [V] +2 0.1 124 A&E 0.7 405 A&E+2 0.2 247 Animal Planet 0.3 215 ARENA 0.6 468 ARENA+2 0.1 169 BBC First 0.8 471 BBC Knowledge 0.3 256 beIN SPORTS 1 0.0 75 beIN SPORTS 2 0.1 136 beIN SPORTS 3 0.7 196 Binge 0.2 148 Boomerang 0.2 116 BoxSets 0.2 162 Cartoon Network 0.4 147 CBeebies 0.1 104 COMEDY CHANNEL 0.3 333 COMEDY CHANNEL+2 0.2 202 Country Music Channel 0.0 56 crime + investigation 1.1 459 Discovery Channel 0.9 610 Discovery Channel+2 0.3 273 Discovery Kids 0.0 36 Discovery Science 0.5 273 Excludes Tasmania *Affiliation changes commenced July 1, 2016. -

“Canned History”: American Newsreels and The

“Canned History”: American Newsreels and the Commodification of Reality, 1927-1945 By Joseph E.J. Clark B.A., University of British Columbia, 1999 M.A., University of British Columbia, 2001 M.A., Brown University, 2004 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of American Civilization at Brown University Providence, Rhode Island May, 2011 © Copyright 2010, by Joseph E.J. Clark This dissertation by Joseph E.J. Clark is accepted in its present form by the Department of American Civilization as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date:____________ _________________________________ Professor Susan Smulyan, Co-director Date:____________ _________________________________ Professor Philip Rosen, Co-director Recommended to the Graduate Council Date:____________ _________________________________ Professor Lynne Joyrich, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date:____________ _________________________________ Dean Peter Weber, Dean of the Graduate School iii Curriculum Vitae Joseph E.J. Clark Date of Birth: July 30, 1975 Place of Birth: Beverley, United Kingdom Education: Ph.D. American Civilization, Brown University, 2011 Master of Arts, American Civilization, Brown University, 2004 Master of Arts, History, University of British Columbia, 2001 Bachelor of Arts, University of British Columbia, 1999 Teaching Experience: Sessional Instructor, Department of Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies, Simon Fraser University, Spring 2010 Sessional Instructor, Department of History, Simon Fraser University, Fall 2008 Sessional Instructor, Department of Theatre, Film, and Creative Writing, University of British Columbia, Spring 2008 Teaching Fellow, Department of American Civilization, Brown University, 2006 Teaching Assistant, Brown University, 2003-2004 Publications: “Double Vision: World War II, Racial Uplift, and the All-American Newsreel’s Pedagogical Address,” in Charles Acland and Haidee Wasson, eds. -

Parade-RGB.Pdf

CONTENTS WELCOME This year, we are proud to present a 06-33 Food & Travel 58-71 Home & Garden 108-111 Format fantastic and diverse line-up of new and We are delighted returning content that we will launch to 06-07 Inside the Box with Jack Stein our buyers at MIPCOM 2017. to welcome you to 58-59 Million Dollar House Hunters 108-109 Restaurant Revolution 08 Andy & Ben Eat Australia 60-61 Luxury Homes Revealed 110-111 Greatest Chefs Parade’s MIPCOM For this market we are bringing 160 hours 09 Andy & Ben Eat the World 62-63 Ready Set Reno of new content which includes a brand 10-11 Sara’s Australia Unveiled 64-65 Find Me a Home in the Country 2017 portfolio of hit new and exciting line-up of lifestyle and 12-13 United Plates of America 66 Australia’s Best Houses factual series being launched. series and originals 14-15 Justine’s Flavours of Fuji 67 Before & After 114-116 4K 68 Build Me a Home 16 Tropical Gourmet: Queensland We are showcasing a number of new and which includes more 69 Dream Home Ideas 17 Tropical Gourmet: New Caledonia 114 Million Dollar House Hunters original series through our joint-venture 70 The Home Team than 1200 hours 18-19 A Rosie Summer 115 Luxury Homes Revealed with Projucer, which sees the launch of 71 Best Gardens Australia 20-21 Tasty Conversations with 116 United Plates of America Jack Stein: Inside the Box, Life is Sweet of programming Audra Morrice: Aussie Road Trip and the much anticipated series Desert 22 Tasty Conversations with Vet, which premiers on Network Seven which can be seen Audra Morrice 74-89 Science & 117 Get in touch next month. -

THE FIVE BEST FOOD FILMS of ALL TIME EFF Speech on Tuesday, March 21, 2017

THE FIVE BEST FOOD FILMS OF ALL TIME EFF Speech on Tuesday, March 21, 2017 By Chris Palmer Mention plan for evening and EcoComedy winners at end and thank TNC. As I’ve said before, this evening is pretentiously called “An Evening with Chris Palmer.” The Festival asked me to do this event about 12 years ago, and I’ve been doing it annually ever since. Tonight I want to talk about the five best food films of all time. Now everyone please stand up, find someone you’ve never met before, and discuss for two minutes the best food films you’ve ever seen. Go! Ask audience members for their ideas! You may have noticed that I didn’t give you much structure for this question. Does food refer to nutrition, agriculture, factory farming, obesity, food waste, junk food, global food trade, or what? Also, by best food films, was I referring to impact? Did the film influence consumers’ purchasing decisions? Did policy makers take action to address, for example, the wretchedness of the standard American diet? Was there a lot of press coverage? Or by best food films, did I simply mean your favorite? As you can see, selecting the five best food films is complicated. Food is important to me for personal reasons. My father died of prostate cancer, and I have his genes. As I’ve researched and learned about cancer, I’ve become convinced that a plant-based diet is the best way to prevent prostate cancer. At the same time, a plant-based diet is one of the most powerful ways to fight climate change and to stop animal cruelty. -

Domino's Pizza

Domino’s Investor Day Presentation – October 10, 2019 AUSTRALIA NEW ZEALAND BELGIUM FRANCE NETHERLANDS JAPAN GERMANY LUXEMBOURG DENMARK Domino’s Presented by DON MEIJ AUSTRALIA NEW ZEALAND BELGIUM FRANCE NETHERLANDS JAPAN GERMANY LUXEMBOURG DENMARK The cornerstone of the Company’s success has been the ability to leverage a diversified Network of both Corporate and Franchised Stores backed by strong store level economic fundamentals and the power and proprietary systems of a global network. The Company plans to continue its expansion throughout Australia and New Zealand and expects that Domino’s Pizza and its Franchisees will continue to benefit from the economies of scale generated by operating the largest pizza Network in Australia. Future growth is expected from new store openings, growth in sales from existing stores and the potential for new store and menu formats. Domino’s pizza Australia new Zealand ltd share offer - 2004 Our view hasn’t changed, but our horizons have. This is a scale business You can’t have 20 or 30 stores. It’s like a 100 storey building, the first 50 or 60 storeys pay for the construction, IT’s When you have those foundations in place that you deliver the real returns. AUSTRALIA NEW ZEALAND BELGIUM FRANCE NETHERLANDS JAPAN GERMANY LUXEMBOURG DENMARK We are a pizza business and distance matters: customers are not going to drive across town to pick up a better deal – you have to be in the right suburb, on the right street, in fact, on the right side of the street. When delivering, time is temperature. Time is money. -

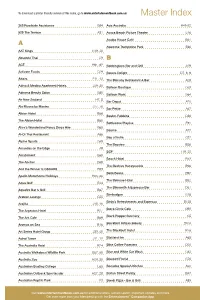

Master Index

To download a printer friendly version of this index, go to www.entertainmentbook.com.au Master Index 365 Roadside Assistance G84 Avis Australia H49-52 529 The Terrace A31 Avoca Beach Picture Theatre E46 Awaba House Café B61 A Awezone Trampoline Park E66 AAT Kings H19, 20 Absolute Thai C9 B ACE H61, 62 Babbingtons Bar and Grill A29 Activate Foods G29 Bakers Delight D7, 8, 9 Adairs F11, 12 The Balcony Restaurant & Bar A28 Adina & Medina Apartment Hotels J29, 30 Balloon Boutique G63 Adnama Beauty Salon G50 Balloon Worx G64 Air New Zealand H7, 8 Bar Depot A20 Ala Moana by Mantra J77, 78 Bar Petite A67 Albion Hotel B66 Baskin-Robbins D36 The Albion Hotel B60 Battlezone Playlive E91 Alice’s Wonderland Fancy Dress Hire G65 Baume A77 Al-Oi Thai Restaurant A66 Bay of India C37 Alpine Sports G69 The Bayview B56 Amandas on the Edge A9 BCF F19, 20 Amazement E69 Beach Hotel B13 The Anchor B68 The Beehive Honeysuckle B96 And the Winner Is OSCARS B53 Bella Beans B97 Apollo Motorhome Holidays H65, 66 The Belmore Hotel B52 Aqua Golf E24 The Bikesmith & Espresso Bar D61 Aqua re Bar & Grill B67 Bimbadgen G18 Arabian Lounge C25 Birdy’s Refreshments and Espresso B125 Arajilla J15, 16 Black Circle Cafe B95 The Argenton Hotel B27 Black Pepper Butchery G5 The Ark Cafe B69 Aromas on Sea B16 Blackbird Artisan Bakery B104 Art Series Hotel Group J39, 40 The Blackbutt Hotel B76 Astral Tower J11, 12 Blaxland Inn A65 The Australia Hotel B24 Bliss Coffee Roasters D66 Australia Walkabout Wildlife Park E87, 88 Blue and White Car Wash G82 Australia Zoo H29, 30 Bluebird Florist G76 Australian Boating College E65 Bocados Spanish Kitchen A50 Australian Outback Spectacular H27, 28 Bolton Street Pantry B47 Australian Reptile Park E3 Bondi Pizza - Bar & Grill A85 Visit www.entertainmentbook.com.au for additional offers, suburb search, important updates and more. -

My-Kitchen-Rules-Presentation.Pdf

REAL FOOD REAL PEOPLE A new batch of home cooks step up to the stove in 2014 in what promises to be one of the most hotly contested series in My Kitchen Rules history. It’s state versus state as teams of two attempt to out-dine and out-wine each other to determine whose kitchen rules. Each team will take turns to transform an ordinary home into an instant restaurant for one pressure cooker night. They’ll plate up a three-course menu designed to impress the judges and their fellow contestants. Manu Feildel and Pete Evans return to host and judge this ultimate home cooking battle. And, this year, they’re bringing some surprises to the table. The MKR Food Truck, a massive red semi-trailer decked out with a state-of-the-art commercial kitchen, is just one of the twists the contestants won’t see coming. It’s going to be one of the toughest challenges MKR contestants have ever faced. It’s going to push even the best cooks to breaking point. In another competition first, the knives are out when select MKR teams form a jury to judge other team’s meals. The judges table will see the return of familiar faces Guest judges: Colin Fassnidge Guy Grossi Karen Martini Liz Egan This year’s contenders: GROUP 1 New South Wales – Annie and Jason (Married cheese makers) Western Australia – Chloe and Kelly (Well-travelled friends) South Australia – Deb and Rick (Married 38 years) Australian Capital Territory – Andrew and Emelia (Newly dating) Queensland – Paul and Blair (Surfer dads) Victoria – Helena and Vikki (Twins) GROUP 2 New South Wales – Uel and Shannelle (Newlyweds) Western Australia – Jess and Felix (Designer and miner) South Australia – Bree and Jessica (Proud mums) Tasmania – Thalia and Bianca (Besties) Queensland – David and Corinne (Couple two years) Victoria – Harry and Christo (Best mates) The top-rating Seven production has built a huge following since it premiered in 2010.