Identification and Control of Leaf Rust of Wheat in Georgia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genome-Wide Association Study for Crown Rust (Puccinia Coronata F. Sp

ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE published: 05 March 2015 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00103 Genome-wide association study for crown rust (Puccinia coronata f. sp. avenae) and powdery mildew (Blumeria graminis f. sp. avenae) resistance in an oat (Avena sativa) collection of commercial varieties and landraces Gracia Montilla-Bascón1†, Nicolas Rispail 1†, Javier Sánchez-Martín1, Diego Rubiales1, Luis A. J. Mur 2 , Tim Langdon 2 , Catherine J. Howarth 2 and Elena Prats1* 1 Institute for Sustainable Agriculture – Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Córdoba, Spain 2 Institute of Biological, Environmental and Rural Sciences, University of Aberystwyth, Aberystwyth, UK Edited by: Diseases caused by crown rust (Puccinia coronata f. sp. avenae) and powdery mildew Jaime Prohens, Universitat Politècnica (Blumeria graminis f. sp. avenae) are among the most important constraints for the oat de València, Spain crop. Breeding for resistance is one of the most effective, economical, and environmentally Reviewed by: friendly means to control these diseases. The purpose of this work was to identify elite Soren K. Rasmussen, University of Copenhagen, Denmark alleles for rust and powdery mildew resistance in oat by association mapping to aid Fernando Martinez, University of selection of resistant plants. To this aim, 177 oat accessions including white and red oat Seville, Spain cultivars and landraces were evaluated for disease resistance and further genotyped with Jason Wallace, Cornell University, USA 31 simple sequence repeat and 15,000 Diversity ArraysTechnology (DArT) markers to reveal association with disease resistance traits. After data curation, 1712 polymorphic markers *Correspondence: Elena Prats, Institute for Sustainable were considered for association analysis. Principal component analysis and a Bayesian Agriculture – Consejo Superior de clustering approach were applied to infer population structure. -

Puccinia Sorghi), in Maize (Zea Mays

Emirates Journal of Food and Agriculture. 2020. 32(1): 11-18 doi: 10.9755/ejfa.2020.v32.i1.2053 http://www.ejfa.me/ RESEARCH ARTICLE Induced resistance to common rust (Puccinia sorghi), in maize (Zea mays) Carmen Alicia Zúñiga-Silvestre1, Carlos De-León-García-de-Alba1*, Victoria Ayala-Escobar1, Víctor A. González-Hernández2 1Instituto de Fitosanidad, Colegio de Postgraduados, Carretera México-Texcoco Km 36.5, Montecillo, Texcoco, Estado de México, C.P. 56230, México, 2Instituto de Fisiología Vegetal, Colegio de Postgraduados, Carretera México-Texcoco Km 36.5, Montecillo, Texcoco, Estado de México, C.P. 56230, México ABSTRACT The common rust of maize (Zea mays L.), caused by Puccinia sorghi Schw., develops pustules on the leaves of maize plants, reducing the leaf area and production of the photoassimilates necessary for grain filling. The host possesses genes coding for different proteins related to the defense mechanisms that prevent the establishment of the pathogen. However, there are susceptible plants that are unable of preventing pathogen attack. This condition depend on biotic and abiotic factors known as inducers of resistance which are able of activating the physico-chemical or morphological defense processes to counteract the invasion of the pathogen. The Ceres XR21 maize hybrid is susceptible to P. sorghi. In this work, maize hybrid was evaluated under a split-split- plot design established in two spring-autumn cycles in the years 2016 and 2017, in which five commercial products of biological and chemical origin reported as inducers of resistance, plus a fungicide were compared. The results showed that trifloxystrobin + tebuconazole (Consist Max®), sprayed on the foliage with 1.5X the commercially recommended dose, showed significant better response in most evaluated variables, because it controlled better the pathogen P. -

Puccinia Psidii Winter MAY10 Tasmania (C)

MAY10Pathogen of the month – May 2010 a b c Fig. 1. Puccinia psidii; (a) Symptoms on Eucalyptus grandis seedling; (b) Stem distortion and multiple branching caused by repeated infections of E. grandis, (c) Syzygium jambos; (d) Psidium guajava; (e) Urediniospores. Photos: A. Alfenas, Federal University of Viçosa, Brazil (a, b,d and e) and M. Glen, University of Tasmania (c). Common Name: Guava rust, Eucalyptus rust d e Winter Disease: Rust in a wide range of Myrtaceous species Classification: K: Fungi, D: Basidiomycota, C: Pucciniomycetes, O: Pucciniales, F: Pucciniaceae Puccinia psidii (Fig. 1) is native to South America and is not present in Australia. It causes rust on a wide range of plant species in the family Myrtaceae. First described on guava, P. psidii became a significant problem in eucalypt plantations in Brazil and also requires control in guava orchards. A new strain of the rust severely affected the allspice industry in Jamaica in the 1930s. P. psidii has spread to Florida, California and Hawaii. In 2007, P. psidii arrived in Japan, on Metrosideros polymorpha cuttings imported from Hawaii. Host Range: epiphytotics on Syzygium jambos in Hawaii, with P. psidii infects young leaves, shoots and fruits of repeated defoliations able to kill 12m tall trees. many species of Myrtaceae. Key Distinguishing Features: Impact: Few rusts are recorded on Myrtaceae. These include In the wild, in its native range, P. psidii has only a P. cygnorum, a telial rust on Kunzea ericifolia, and minor effect. As eucalypt plantations in Brazil are Physopella xanthostemonis on Xanthostemon spp. in largely clonal, impact in areas with a suitable climate Australia. -

Induced Resistance in Wheat

https://doi.org/10.35662/unine-thesis-2819 Induced resistance in wheat A dissertation submitted to the University of Neuchâtel for the degree of Doctor in Naturel Science by Fares BELLAMECHE Thesis direction Prof. Brigitte Mauch-Mani Dr. Fabio Mascher Thesis committee Prof. Brigitte Mauch-Mani, University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland Prof. Daniel Croll, University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland Dr. Fabio Mascher, Agroscope, Changins, Switzerland Prof. Victor Flors, University of Jaume I, Castellon, Spain Defense on the 6th of March 2020 University of Neuchâtel Summary During evolution, plants have developed a variety of chemical and physical defences to protect themselves from stressors. In addition to constitutive defences, plants possess inducible mechanisms that are activated in the presence of the pathogen. Also, plants are capable of enhancing their defensive level once they are properly stimulated with non-pathogenic organisms or chemical stimuli. This phenomenon is called induced resistance (IR) and it was widely reported in studies with dicotyledonous plants. However, mechanisms governing IR in monocots are still poorly investigated. Hence, the aim of this thesis was to study the efficacy of IR to control wheat diseases such leaf rust and Septoria tritici blotch. In this thesis histological and transcriptomic analysis were conducted in order to better understand mechanisms related to IR in monocots and more specifically in wheat plants. Successful use of beneficial rhizobacteria requires their presence and activity at the appropriate level without any harmful effect to host plant. In a first step, the interaction between Pseudomonas protegens CHA0 (CHA0) and wheat was assessed. Our results demonstrated that CHA0 did not affect wheat seed germination and was able to colonize and persist on wheat roots with a beneficial effect on plant growth. -

Image-Based Wheat Fungi Diseases Identification by Deep

plants Article Image-Based Wheat Fungi Diseases Identification by Deep Learning Mikhail A. Genaev 1,2,3, Ekaterina S. Skolotneva 1,2, Elena I. Gultyaeva 4 , Elena A. Orlova 5, Nina P. Bechtold 5 and Dmitry A. Afonnikov 1,2,3,* 1 Institute of Cytology and Genetics, Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 630090 Novosibirsk, Russia; [email protected] (M.A.G.); [email protected] (E.S.S.) 2 Faculty of Natural Sciences, Novosibirsk State University, 630090 Novosibirsk, Russia 3 Kurchatov Genomics Center, Institute of Cytology and Genetics, Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 630090 Novosibirsk, Russia 4 All Russian Institute of Plant Protection, Pushkin, 196608 St. Petersburg, Russia; [email protected] 5 Siberian Research Institute of Plant Production and Breeding, Branch of the Institute of Cytology and Genetics, Siberian Branch of Russian Academy of Sciences, 630501 Krasnoobsk, Russia; [email protected] (E.A.O.); [email protected] (N.P.B.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +7-(383)-363-49-63 Abstract: Diseases of cereals caused by pathogenic fungi can significantly reduce crop yields. Many cultures are exposed to them. The disease is difficult to control on a large scale; thus, one of the relevant approaches is the crop field monitoring, which helps to identify the disease at an early stage and take measures to prevent its spread. One of the effective control methods is disease identification based on the analysis of digital images, with the possibility of obtaining them in field conditions, Citation: Genaev, M.A.; Skolotneva, using mobile devices. In this work, we propose a method for the recognition of five fungal diseases E.S.; Gultyaeva, E.I.; Orlova, E.A.; of wheat shoots (leaf rust, stem rust, yellow rust, powdery mildew, and septoria), both separately Bechtold, N.P.; Afonnikov, D.A. -

Wheat Leaf Rust

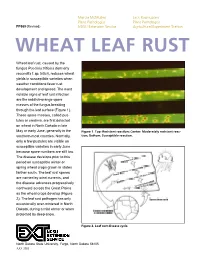

Marcia McMullen Jack Rasmussen Plant Pathologist Plant Pathologist PP589 (Revised) NDSU Extension Service Agricultural Experiment Station WHEAT LEAF RUST Wheat leaf rust, caused by the fungus Puccinia triticina (formerly recondita f. sp. tritici), reduces wheat yields in susceptible varieties when weather conditions favor rust development and spread. The most notable signs of leaf rust infection are the reddish-orange spore masses of the fungus breaking through the leaf surface (Figure 1). These spore masses, called pus- tules or uredinia, are first detected on wheat in North Dakota in late May or early June, generally in the Figure 1. Top: Resistant reaction; Center: Moderately resistant reac- southern-most counties. Normally, tion; Bottom: Susceptible reaction. only a few pustules are visible on susceptible varieties in early June because spore numbers are still low. The disease develops prior to this period on susceptible winter or spring wheat crops grown in states farther south. The leaf rust spores are carried by wind currents, and the disease advances progressively northward across the Great Plains as the wheat crops develop (Figure 2). The leaf rust pathogen has only occasionally over-wintered in North Dakota, during a mild winter or when protected by deep snow. Figure 2. Leaf rust disease cycle. North Dakota State University, Fargo, North Dakota 58105 JULY 2002 The Disease The following factors must be present for wheat leaf rust infection to occur: viable spores; susceptible or moder- ately susceptible wheat plants; moisture on the leaves (six to eight hours of dew); and favorable temperatures (60 to 80 degrees Fahrenheit). Relatively cool nights combined with warm days are excellent conditions for disease development. -

Cereal Rye Section 9 Diseases

SOUTHERN SEPTEMBER 2018 CEREAL RYE SECTION 9 DISEASES TOOLS FOR DIAGNOSING CEREAL DISEASE | ERGOT | TAKE-ALL | RUSTS | YELLOW LEAF SPOT (TAN SPOT) | FUSARIUM: CROWN ROT AND FHB | COMMON ROOT ROT | SMUT | RHIZOCTONIA ROOT ROT | CEREAL FUNGICIDES | DISEASE FOLLOWING EXTREME WEATHER EVENTS SOUTHERN JANUARY 2018 SECTION 9 CEREAL rye Diseases Key messages • Rye has good tolerance to cereal root diseases. • The most important disease of rye is ergot (Claviceps purpurea). It is important to realise that feeding stock with ergot infested grain can result in serious losses. Grain with three ergots per 1,000 kernels can be toxic. 1 • Stem and leaf rusts can usually be seen on cereal rye in most years, but they are only occasionally a serious problem. 2 • All commercial cereal rye varieties have resistance to the current pathotypes of stripe rust. However, the out-crossing nature of the species will mean that under high disease pressure, a proportion of the crop (approaching 15–20% of the plant population) may show evidence of the disease. Other diseases are usually insignificant. • Cereal rye has tolerance to take-all, making it a useful break crop following grassy pastures. 3 • Bevy is a host for the root disease take-all and this should be carefully monitored. 4 General disease management strategies: • Use resistant or partially resistant varieties. • Use disease-free seed. • Use fungicidal seed treatments to kill fungi carried on the seed coat or in the seed. • Have a planned in-crop fungicide regime. • Conduct in-crop disease audits to determine the severity of the disease. This can be used as a tool to determine what crop is grown in what paddock the following year. -

TCJP an Improved Method to Quantify <I>Puccinia Coronata</I> F

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by UNL | Libraries University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln U.S. Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty Research Service, Lincoln, Nebraska 2010 TCJP An improved method to quantify Puccinia coronata f. sp. avenae DNA in the host Avena sativa M. Acevedo USDA-ARS, [email protected] E. W. Jackson USDA-ARS A. Sturbaum USDA-ARS H. W. Ohm Purdue University J. M. Bonman USDA-ARS Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdaarsfacpub Part of the Agricultural Science Commons Acevedo, M.; Jackson, E. W.; Sturbaum, A.; Ohm, H. W.; and Bonman, J. M., "TCJP An improved method to quantify Puccinia coronata f. sp. avenae DNA in the host Avena sativa" (2010). Publications from USDA- ARS / UNL Faculty. 509. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdaarsfacpub/509 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Research Service, Lincoln, Nebraska at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Can. J. Plant Pathol. (2010), 32(2): 215–224 Genetics and resistance/Génétique et résistance AnTCJP improved method to quantify Puccinia coronata f. sp. avenae DNA in the host Avena sativa M.Crown rust of oat ACEVEDO1, E. W. JACKSON1, A. STURBAUM1, H. W. OHM2 AND J. M. BONMAN1 1USDA-ARS Small Grains and Potato Germplasm Research Unit, 1691 S. 2700 W., Aberdeen, ID 83210, USA 2Department of Agronomy, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907, USA (Accepted 1 March 2010) Abstract: Identification and genetic mapping of loci conferring resistance to polycyclic pathogens such as the rust fungi depends on accurate measurement of disease resistance. -

Virulence of Puccinia Triticina on Wheat in Iran

African Journal of Plant Science Vol. 4 (2), pp. 026-031, February 2010 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/ajps ISSN 1996-0824 © 2010 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Virulence of Puccinia triticina on wheat in Iran S. Elyasi-Gomari Azad Islamic University, Shoushtar Branch, Faculty of Agriculture, Shoushtar, Iran. E-mail: [email protected]. Accepted 12 January, 2010 Wheat leaf rust is controlled mainly by race-specific resistance. To be effective, breeding wheat for resistance to leaf rust requires knowledge of virulence diversity in local populations of the pathogen. Collections of Puccinia triticina were made from rust-infected wheat leaves on the territory of Khuzestan province (south-west) in Iran during 2008 - 2009. In 2009, up to 20 isolates each of the seven most common leaf rust races plus 8 -10 isolates of unnamed races were tested for virulence to 35 near- isogenic wheat lines with different single Lr genes for leaf rust resistance. The lines with Lr9, Lr25, Lr28 and Lr29 gene were resistant to all of the isolates. Few isolates of known races but most isolates of the new, unnamed races were virulent on Lr19. The 35 Lr gene lines were also exposed to mixed race inoculum in field plots to tests effectiveness of their resistance. No leaf rust damage occurred on Lr9, Lr25, Lr28 and Lr29 in the field, and lines with Lr19, Lr16, Lr18, Lr35, Lr36, Lr37 and the combination Lr27 + Lr31 showed less than 15% severity. A total of 500 isolates of P. triticina obtained from five commercial varieties of wheat at two locations in the eastern and northern parts of the Khuzestan region were identified to race using the eight standard leaf rust differential varieties of Johnson and Browder. -

Population Biology of Switchgrass Rust

POPULATION BIOLOGY OF SWITCHGRASS RUST (Puccinia emaculata Schw.) By GABRIELA KARINA ORQUERA DELGADO Bachelor of Science in Biotechnology Escuela Politécnica del Ejército (ESPE) Quito, Ecuador 2011 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE July, 2014 POPULATION BIOLOGY OF SWITCHGRASS RUST (Puccinia emaculata Schw.) Thesis Approved: Dr. Stephen Marek Thesis Adviser Dr. Carla Garzon Dr. Robert M. Hunger ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS For their guidance and support, I express sincere gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Marek, who has supported thought my thesis with his patience and knowledge whilst allowing me the room to work in my own way. One simply could not wish for a better or friendlier supervisor. I give special thanks to M.S. Maxwell Gilley (Mississippi State University), Dr. Bing Yang (Iowa State University), Arvid Boe (South Dakota State University) and Dr. Bingyu Zhao (Virginia State), for providing switchgrass rust samples used in this study and M.S. Andrea Payne, for her assistance during my writing process. I would like to recognize Patricia Garrido and Francisco Flores for their guidance, assistance, and friendship. To my family and friends for being always the support and energy I needed to follow my dreams. iii Acknowledgements reflect the views of the author and are not endorsed by committee members or Oklahoma State University. Name: GABRIELA KARINA ORQUERA DELGADO Date of Degree: JULY, 2014 Title of Study: POPULATION BIOLOGY OF SWITCHGRASS RUST (Puccinia emaculata Schw.) Major Field: ENTOMOLOGY AND PLANT PATHOLOGY Abstract: Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.) is a perennial warm season grass native to a large portion of North America. -

Integrated Management of Southern Corn Rust and Northern Corn

INTEGRATED MANAGEMENT OF SOUTHERN CORN RUST AND NORTHERN CORN LEAF BLIGHT USING HYBRIDS AND FUNGICIDES by SUZETTE MAGDALENE SEÑEREZ ARCIBAL (Under the Direction of Robert C. Kemerait, Jr.) ABSTRACT Southern corn rust (SCR) caused by Puccinia polysora and northern corn leaf blight (NCLB) caused by Exserohilum turcicum are important foliar diseases of corn in the southern United States. Field experiments were conducted to determine the effect of hybrid, fungicide and timing of fungicide application on NCLB and SCR epidemics and corn yield. The Rpp9-virulent and Rpp9-avirulent races of P. polysora were characterized in the field. Onset of SCR in Pioneer 33M52 was delayed in early-planted trials but not in later-planted trials. Area under the disease progress curves (AUDPC) for SCR were lower and yields were higher in Pioneer 33M52 than in Pioneer 33M57 when this disease was severe. Fungicides were usually most effective when applied near disease onset. When both diseases were severe, multiple fungicide applications improved disease management and yield. In vitro sensitivity assays indicated a range of EC50 values from 0.008 to 0.155 μg/ml. These results can be used to further develop management guidelines for SCR and NCLB. INDEX WORDS: Southern corn rust, Puccinia polysora, Rpp9-virulent race, northern corn leaf blight, Exserohilum turcicum, pyraclostrobin, metconazole, fluxapyroxad, fungicide timing, area under the disease progress curve, severity, incidence, necrosis, yield, fungicide sensitivity INTEGRATED MANAGEMENT OF SOUTHERN CORN -

Asparagus Rust (Puccinia Asparagi) (Puccinia Matters-Of- Facts Seasons Infection

DEPARTMENT OF PRIMARY INDUSTRIES Vegetable Matters-of-Facts Number 12 Asparagus Rust February (Puccinia asparagi) 2004 • Rust disease of asparagus is caused by the fungus Puccinia asparagi. • Rust is only a problem on fern not the spears. • Infected fern is defoliated reducing the potential yield of next seasons crop. • First detected in Queensland in 2000 and in Victoria in 2003 Infection and symptoms Infections of asparagus rust begin in spring from over-wintering spores on crop debris. Rust has several visual spore stages known as the orange, red and black spore stages. Visual symptoms of infection start in spring/summer with light green pustules on new emerging fern which mature into yellow or pale orange pustules. In early to mid summer when conditions are warm and moist, the orange spores spread to new fern growth producing brick red pustules on stalks, branches and leaves of the fern. These develop into powdery masses of rust-red coloured spores which reinfect the fern. Infected fern begins to yellow, defoliate and die back prematurely. In late autumn and winter the red-coloured pustules start to produce black spores and slowly convert in appearance to a powdery mass of jet-black spores. This is the over-wintering stage of Asparagus the fungus and the source of the next seasons infection. Control Stratagies Complete eradication of the disease is not feasible as rust spores are spread by wind. However rust can be controlled with proper fern management. • Scout for early signs for rust and implement fungicide spray program • Volunteer and other unwanted asparagus plantings must be destroyed to control infection sources.