This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of Glasgow and Clyde Valley 3 Day Itinerary

The City of Glasgow and The Clyde Valley Itinerary - 3 Days 01. Kelvin Hall The Burrell Collection A unique partnership between Glasgow Life, the University of The famous Burrell Collection, one of the greatest art collections Glasgow and the National Library of Scotland has resulted in this ever amassed by one person and consisting of more than 8,000 historic building being transformed into an exciting new centre of objects, will reopen in Spring 2021. Housed in a new home in cultural excellence. Your clients can visit Kelvin Hall for free and see Glasgow’s Pollok Country Park, the Burrell’s renaissance will see the National Library of Scotland’s Moving Image Archive or take a the creation of an energy efficient, modern museum that will tour of the Glasgow Museums’ and the Hunterian’s store, alongside enable your clients to enjoy and better connect with the collection. enjoy a state-of-the art Glasgow Club health and fitness centre. The displays range from work by major artists including Rodin, Degas and Cézanne. 1445 Argyle Street Glasgow, G3 8AW Pollok Country Park www.kelvinhall.org.uk 2060 Pollokshaws Road Link to Trade Website Glasgow. G43 1AT www.glasgowlife.org.uk Link to Trade Website Distance between Kelvin Hall and Clydeside Distillery is 1.5 miles/2.4km Distance between The Burrell Collection and Glasgow city centre The Clydeside Distillery is 5 miles/8km The Clydeside Distillery is a Single Malt Scotch Whisky distillery, visitor experience, café, and specialist whisky shop in the heart of Glasgow. At Glasgow’s first dedicated Single Malt Scotch Whisky Distillery for over 100 years, your clients can choose a variety of tours, including whisky and chocolate paring. -

Scotland's Historic Cities D N a L T O C

Scotland's Historic Cities D N A L T O C Tinto Hotel S Holiday Inn Edinburgh Edinburgh Castle ©Paul Tompkins,Scottish ViewPoint 5 DAYS from only £142 Tinto Hotel Holiday Inn Edinburgh NEW What To Do Biggar Edinburgh Edinburgh Scotland’s capital offers endless possibilities including DOUBLE FOR TRADITIONAL DOUBLE FOR Edinburgh Castle, Royal Yacht Britannia, The Queen’s EXCELLENT SINGLE SCOTTISH SINGLE official Scottish residence – The Palace of Holyroodhouse PUBLIC AREAS and the Scotch Whisky Heritage Centre. The Royal Mile, OCCUPANCY HOTEL OCCUPANCY the walk of kings and queens, between Edinburgh Castle and Holyrood Palace is a must to enjoy Edinburgh at its historical best. If the modern is more for you, then the This charming 3 star property was originally built as a This 4 star Holiday Inn is located on the main road to shops and Georgian buildings of Princes Street are railway hotel and has undergone refurbishment to return it Edinburgh city centre being only 2 miles from Princes Street. perfect for those browsing for a bargain! to its former glory. With wonderfully atmospheric public This hotel has a spacious modern open plan reception, areas and a large entertainment area, this small hotel is restaurant, lounge and bar. All 303 air conditioned Glasgow deceptively large. Each of the 40 bedrooms is traditionally bedrooms are equipped with tea/coffee making facilities and Scotland’s second city has much to offer the visitor. furnished with facilities including TV, hairdryer, and TV. Leisure facilities within the hotel include swimming pool, Since its regeneration, Glasgow is now one of the most tea/coffee making facilities. -

Missions and Film Jamie S

Missions and Film Jamie S. Scott e are all familiar with the phenomenon of the “Jesus” city children like the film’s abused New York newsboy, Little Wfilm, but various kinds of movies—some adapted from Joe. In Susan Rocks the Boat (1916; dir. Paul Powell) a society girl literature or life, some original in conception—have portrayed a discovers meaning in life after founding the Joan of Arc Mission, variety of Christian missions and missionaries. If “Jesus” films while a disgraced seminarian finds redemption serving in an give us different readings of the kerygmatic paradox of divine urban mission in The Waifs (1916; dir. Scott Sidney). New York’s incarnation, pictures about missions and missionaries explore the East Side mission anchors tales of betrayal and fidelity inTo Him entirely human question: Who is or is not the model Christian? That Hath (1918; dir. Oscar Apfel), and bankrolling a mission Silent movies featured various forms of evangelism, usually rekindles a wealthy couple’s weary marriage in Playthings of Pas- Protestant. The trope of evangelism continued in big-screen and sion (1919; dir. Wallace Worsley). Luckless lovers from different later made-for-television “talkies,” social strata find a fresh start together including musicals. Biographical at the End of the Trail mission in pictures and documentaries have Virtuous Sinners (1919; dir. Emmett depicted evangelists in feature films J. Flynn), and a Salvation Army mis- and television productions, and sion worker in New York’s Bowery recent years have seen the burgeon- district reconciles with the son of the ing of Christian cinema as a distinct wealthy businessman who stole her genre. -

National Programme 2017/2018 2

National Programme 2017/2018 2 National Programme 2017/2018 3 National Programme 2017/2018 National Programme 2017/2018 1 National Programme Across Scotland Through our National Strategy 2016–2020, Across Scotland, Working to Engage and Inspire, we are endeavouring to bring our collections, expertise and programmes to people, museums and communities throughout Scotland. In 2017/18 we worked in all of Scotland’s 32 local authority areas to deliver a wide-ranging programme which included touring exhibitions and loans, community engagement projects, learning and digital programmes as well as support for collections development through the National Fund for Acquisitions, expert advice from our specialist staff and skills development through our National Training Programme. As part of our drive to engage young people in STEM learning (Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths), we developed Powering Up, a national science engagement programme for schools. Funded by the ScottishPower Foundation, we delivered workshops on wind, solar and wave energy in partnership with the National Mining Museum, the Scottish Maritime Museum and New Lanark World Heritage Site. In January 2017, as part of the final phase of redevelopment of the National Museum of Scotland, we launched an ambitious national programme to support engagement with Ancient Egyptian and East Asian collections held in museums across Scotland. Funded by the National Lottery and the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, the project is providing national partnership exhibitions and supporting collection reviews, skills development and new approaches to audience engagement. All of this work is contributing to our ambition to share our collections and expertise as widely as possible, ensuring that we are a truly national museum for Scotland. -

By Kathryn Sutherland

JANE AUSTEN’S DEALINGS WITH JOHN MURRAY AND HIS FIRM by kathryn sutherland Jane Austen had dealings with several publishers, eventually issuing her novels through two: Thomas Egerton and John Murray. For both, Austen may have been their first female novelist. This essay examines Austen-related materials in the John Murray Archive in the National Library of Scotland. It works in two directions: it considers references to Austen in the papers of John Murray II, finding some previously overlooked details; and it uses the example of Austen to draw out some implications of searching amongst the diverse papers of a publishing house for evidence of a relatively unknown (at the time) author. Together, the two approaches argue for the value of archival work in providing a fuller context of analysis. After an overview of Austen’s relations with Egerton and Murray, the essay takes the form of two case studies. The first traces a chance connection in the Murray papers between Austen’s fortunes and those of her Swiss contemporary, Germaine de Stae¨l. The second re-examines Austen’s move from Egerton to Murray, and the part played in this by William Gifford, editor of Murray’s Quarterly Review and his regular reader for the press. Although Murray made his offer for Emma in autumn 1815, letters in the archive show Gifford advising him on one, possibly two, of Austen’s novels a year earlier, in 1814. Together, these studies track early testimony to authorial esteem. The essay also attempts to draw out some methodological implications of archival work, among which are the broad informational parameters we need to set for the recovery of evidence. -

BEST of BRITISH 16 FASCINATING DAYS | LONDON RETURN We Take the Time to Do Britain Justice…

BEST OF BRITISH 16 FASCINATING DAYS | LONDON RETURN We take the time to do Britain justice…. from Stonehenge to the ‘bravehearts’ of Scotland and Tintern’s romantic Abbey. Discover the Kingmakers of Warwick and learn of Australia’s own heritage in Captain Cook’s Whitby. Soak up the history of Shakespeare in Stratford-upon-Avon and indulge in traditional British fare. As a finale, be treated like royalty with an overnight stay in magnificent Leeds Castle! TOUR INCLUSIONS ALL excursions, scenic drives, sightseeing and entrances as described Fully escorted by our experienced Tour Manager Travel in a first class air-conditioned touring coach 15 nights specially selected hotel accommodation Hotel porterage (1 bag per person) 25 Meals – including breakfast daily, 1 lunch and 9 dinners Tea, coffee and a complimentary beverage with all included dinners Afternoon tea at Betty’s tearooms in Harrogate Hand Selected Albatross Experiences - Private cruise Lake Windermere, Captain Cook's Whitby Local guides as described in the itinerary ALL tips to your Tour Manager, Driver and Local Guides Personal audio system whilst on tour Free WiFi at hotels Add a subheading “The places we visited were wonderful. We enjoyed the unique THE ALBATROSS DIFFERENCE hotel accommodation and the most Leisurely 2 and 3 night stays special place was of course Leeds Small group sizes - from just 10 to 28 Castle where we were made to feel Genuinely inclusive, NO extra 'on tour' costs very important.” Ellaine & Kim Stay in traditional style hotels in superb locations Easier days with 'My Time' guaranteed! TOUR ITINERARY: BEST OF BRITISH Day 1: Stonehenge and Bath Your tour departs from central London at 9am. -

New Lanark World Heritage Site

New Lanark World Heritage Site A Short Guide April 2019 NIO M O U N IM D R T IA A L • • P • • W L L O A I R D L D N H O E M R E I T N A I G O E • PATRI M United Nations New Lanark Educational, Scientific and inscribed on the World Cultural Organization Heritage List in 2001 Contents Introduction 1 New Lanark WHS: Key Facts 2 The World Heritage Site and Bufer Zone 3 Statement of Outstanding Universal Value 5 Managing New Lanark 6 Planning and New Lanark WHS 8 Further Information and Contacts 10 Cover image: Aerial view of New Lanark. Introduction This short guide is an introduction to New Lanark World Heritage Site (WHS), its inscription on the World Heritage List, and its management and governance. It is one of a series of Site-specifc short guides for each of Scotland’s six WHS. For information outlining what World Heritage status is and what it means, the responsibilities and benefts attendant upon achieving World Heritage status, and current approaches to protection and management see the SHETLAND World Heritage in Scotland short guide. See Further Information and Contacts or more information. ORKNEY 1 Kirkwall Western Isles Stornoway St kilda 2 Inverness Aberdeen World Heritage Sites in Scotland KEY: Perth 1 Heart of Neolithic Orkney 2 St Kilda Forth Bridge 6 5 3 3 Frontiers of the Roman Empire: Edinburgh Antonine Wall Glasgow 4 4 NEW LANARK 5 Old and New Towns of Edinburgh 6 Forth Bridge 1 New Lanark WHS: Key Facts • Inscribed on the World Heritage List in • New Lanark village remains a thriving 2001 as a cultural WHS. -

Youth Travel SAMPLE ITINERARY

Youth Travel SAMPLE ITINERARY For all your travel trade needs: www.visitscotlandtraveltrade.com Day One Riverside Museum Riverside Museum is Glasgow's award-winning transport museum. With over 3,000 objects on display there's everything from skateboards to locomotives, paintings to prams and cars to a Stormtrooper. Your clients can get hands on with our interactive displays, walk through Glasgow streets and visit the shops, bar and subway. Riverside Museum Pointhouse Place, Glasgow, G3 8RS W: http://www.glasgowlife.org.uk/museums Glasgow Powerboats A unique city-centre experience. Glasgow Powerboats offer fantastic fast boat trip experiences on the River Clyde from Pacific Quay in the heart of Glasgow right outside the BBC Scotland HQ. From a 15-minute City Centre transfer to a full day down the water they can tailor trips to your itinerary. Glasgow Powerboats 50 Pacific Quay, Glasgow, G51 1EA W: https://powerboatsglasgow.com/ Glasgow Science Centre Glasgow Science Centre is one of Scotland's must-see visitor attractions. It has lots of activities to keep visitors of all ages entertained for hours. There are two acres of interactive exhibits, workshops, shows, activities, a planetarium and an IMAX cinema. Your clients can cast off in The Big Explorer and splash about in the Waterways exhibit, put on a puppet show and master the bubble wall. Located on the Pacific Quay in Glasgow City Centre just a 10-minute train journey from Glasgow Central Station. Glasgow Science Centre 50 Pacific Quay, Glasgow, G51 1EA For all your travel trade needs: www.visitscotlandtraveltrade.com W: https://www.glasgowsciencecentre.org/ Scottish Maritime Museum Based in the West of Scotland, with sites in Irvine and Dumbarton, the Scottish Maritime Museum holds an important nationally recognised collection, encompassing a variety of historic vessels, artefacts, fascinating personal items and the largest collection of shipbuilding tools and machinery in the country. -

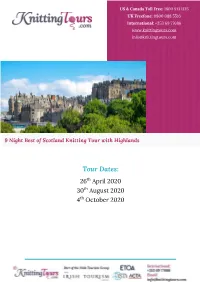

Tour Dates: 26Th April 2020 30Th August 2020 4Th October 2020

Get in Touch: US & Canada Toll Free: 1800 913 1135 UK Freefone: 0800 088 5516 International: +353 69 77686 www.knittingtours.com [email protected] 9 Night Best of Scotland Knitting Tour with Highlands Tour Dates: 26th April 2020 30th August 2020 4th October 2020 Tour Overview This Scottish knitting tour will help you experience craft in Scotland with an emphasis on knitting. Your tour will include a tour of Edinburgh and Edinburgh Castle. Visit New Lanark Mill, a famous world heritage site, the village of Sanquhar known for its unique Sanquhar knitting pattern. You will spend time in Glasgow, a port city on the River Clyde and the largest city in Scotland, from here we will travel along the shores of Loch Lomond to Auchindrain Township where you will be treated to a special recreation of ‘waulking with wool’. On this tour we will visit Johnsons Mill in Elgin, Scotland’s only remaining vertical mill! In Fife we will visit Claddach farm and learn more about the Scottish sheep, goats and Alpacas that are reared to produce the finest Scottish wool. There will be three half day workshops on this tour: we will meet with Emily from Tin Can Knits in Edinburgh, in Elgin we will enjoy a workshop on our April tour with ERIBE and our August and October tours with Sarah Berry of North Child and in Fife you will take part in a workshop with Di Gilpin and her team. Of course no tour of Scotland is complete without visiting a whisky distillery! Your tour includes a tour of a Speyside Distillery with a whisky tasting in Scotland’s famous whisky producing area. -

Download (2631Kb)

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/58603 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. A Special Relationship: The British Empire in British and American Cinema, 1930-1960 Sara Rose Johnstone For Doctorate of Philosophy in Film and Television Studies University of Warwick Film and Television Studies April 2013 ii Contents List of figures iii Acknowledgments iv Declaration v Thesis Abstract vi Introduction: Imperial Film Scholarship: A Critical Review 1 1. The Jewel in the Crown in Cinema of the 1930s 34 2. The Dark Continent: The Screen Representation of Colonial Africa in the 1930s 65 3. Wartime Imperialism, Reinventing the Empire 107 4. Post-Colonial India in the New World Order 151 5. Modern Africa according to Hollywood and British Filmmakers 185 6. Hollywood, Britain and the IRA 218 Conclusion 255 Filmography 261 Bibliography 265 iii Figures 2.1 Wee Willie Winkie and Susannah of the Mounties Press Book Adverts 52 3.1 Argentinian poster, American poster, Hungarian poster and British poster for Sanders of the River 86 3.2 Paul Robeson and Elizabeth Welch arriving in Africa in Song of Freedom 92 3.3 Cedric Hardwicke and un-credited actor in Stanley and Livingstone -

White Man's Country: the Image of Africa in the American Century By

White Man’s Country: The Image of Africa in the American Century By Aaron John Bady A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Bryan Wagner, Chair Professor Donna Jones Professor Scott Saul Professor Michael Watts Fall 2013 Abstract White Men’s Country: The Image of Africa in the American Century By Aaron John Bady Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Berkeley Professor Bryan Wagner, Chair It is often taken for granted that “the West’s image of Africa” is a dark and savage jungle, the “white man’s grave” which formed the backdrop for Joseph Conrad’s hyper-canonical Heart of Darkness. In the wake of decolonization and independence, African writers like Chinua Achebe and Ngugi wa Thiong’o provided alternate accounts of the continent, at a moment when doing so was rightly seen to be “The Empire Writes Back.” Yet in the years since then, “going beyond the clichés” has itself become a kind of cliché. In the last decade in particular, the global investment class has taken up the appeal to “Re-brand Africa” with a vengeance. Providing positive images of Africa is not necessarily a radical critique of empire’s enduring legacies, in other words; it can also be an effort to brand and market “Africa” as a product for capital speculation. In White Men’s Country: The Image of Africa in the American Century, I describe how American literary investments in Africa grew, alongside the slow decline of European cultural imperialism. -

July 1978 Scv^ Monthly for the Press && the Museum of Modern Art Frl 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y

d^c July 1978 ScV^ Monthly for the Press && The Museum of Modern Art frl 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Department of Public Information, (212)956-2648 What' s New Page 1 What's Coming Up Page 2 Current Exhibitions Page 3-4 Gallery Talks, Special Events Page 4-5 Ongoing Page Museum Hours, Admission Fees Page 6 Events for Children , Page 6 WHAT'S NEW DRAWINGS Artists and Writers Jul 10—Sep 24 An exhibition of 75 drawings from the Museum Collection ranging in date from 1889 to 1976. These drawings are portraits of 20th- century American and European painters and sculptors, poets and philosophers, novelists and critics. Portraits of writers in clude those of John Ashbery, Joe Bousquet, Bertolt Brecht, John Dewey, Iwan Goll, Max Jacob, James Joyce, Frank O'Hara, Kenneth Koch, Katherine Anne Porter, Albert Schweitzer, Gertrude Stein, Tristan Tzara, and Glenway Wescott. Among the artists represent ed by self-portraits are Botero, Chagall, Duchamp, Hartley, Kirchner, Laurencin, Matisse, Orozco, Samaras, Shahn, Sheeler, and Spilliaert. Directed by William S. Lieberman, Director, De partment of Drawings. (Sachs Galleries, 3rd floor) VARIETY OF MEDIA Selections from the Art Lending Service Jul 10—Sep 5 An exhibition/sale of works in a variety of media. (Penthouse, 6th floor) PHOTOGRAPHY Mirrors and Windows: American Photography Since 1960 Jul 28—Oct 2 This exhibition of approximately 200 prints attempts to provide a critical overview of the new American photography of the past Press Preview two decades. The central thesis of the exhibition claims that Jul 26 the basic dichotomy in contemporary photography distinguishes llam-4pm those who think of photography fundamentally as a means of self- expnession from those who think of it as a method of exploration.