South Florida Buildings Aiming for Green Standard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lobbying in Miami-Dade County

Miami-Dade County Board of County Commissioners Lobbying In Miami-Dade County 2013 Annual Report HARVEY RUVIN, Clerk of Circuit & County Courts and Ex-Officio Clerk to the Miami-Dade Board of County Commissioners Prepared by: Christopher Agrippa, Director Clerk of the Board Division Miami-Dade County Board of County Commissioners Lobbyist Registration SECTION I REGISTRATION BY LOBBYIST Printed on: 1/7/2014 Page 3 of 72 Miami-Dade County Board of County Commissioners Lobbyist Registration A ALFORD, JONATHAN 2440 RESEARCH BLVD ROCKVILLE MD 20850 ABOODY, JASON 9965 FEDERAL DRIVE OTSUKA AMERICA PHARMACEUTICALS COLORADO SPRINGS CO 80921 THE SPECTRANETICS CORPORATION ALLY, DEANNA 700 10TH AVENUE SOUTH SUITE 20 MINNEAPOLIS MI 55415 ABRAMS, MICHAEL 801 BRICKELL AVENUE STE 900 ZYGA TECHNOLOGY, INC. MIAMI FL 33131 BALLARD PARTNERS ALSCHULER, JR, JOHN H 99 HUDSON ST 3 FLOOR NEW YORK NY 10013 ACOSTA, EDWARD 100 DENNIS DRIVE BECKHAM BRAND LIMITED READING PA 19606 SURGICAL SPECIALITIES CORPORATION ALVAREZ, JORGE A 95 MERRICK WAY 7TH FLOOR CORAL GABLES FL 33134 ACOSTA, PABLO 131 MADEIRA AVE PH COMMUNITY CONSULTANTS, INC. CORAL GABLES FL 33134 CLEVER DEVICES INC AMSTER, MATTHEW G COMTECH ENGINEERING 200 S BISCAYNE BLVD Ste 850 MIAMI FL 33131 FLORIDA DEVELOPMENT GROUP, INC METRO GAS FL LLC NETZACH YISROEL TORAH CENTER, INC MIAMI DOWNTOWN DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY SURGICAL PARK CENTER, LTD ADLER, BRIAN ANDARA, CHRISTOPHER D 1450 BRICKELL AVENUE SUITE 2300 11767 MEDICAL LLC MIAMI FL 33131 MIAMI FL 33156 19301 WEST DIXIE STORAGE, LLC ORBIS MEDICAL ANSALDOBREDA, INC ANDERSON, MELISSA P MIRON REALTY COMPANY 8555 NW 64TH STREET MODANI CAPITAL LLC DORAL FL 33166 PMG AVENTURA, LLC CROWN CASTLE USA SONNENKLAR LIMITED PARTNERSHIP THE ASSOC. -

ULI: Returns on Resilience the Business Case

Returns on Resilience THE BUSINESS CASE Cover photo: A view of the green roof and main office tower at 1450 Brickell Avenue, with Biscayne Bay beyond. Robin Hill © 2015 Urban Land Institute 1025 Thomas Jefferson Street, NW Suite 500 West Washington, DC 20007-5201 All rights reserved. Reproduction or use of the whole or any part of the contents without written permission of the copyright holder is prohibited. Recommended bibliographic listing: Urban Land Institute: Returns on Resilience: The Business Case. ULI Center for Sustainability. Washington, D.C.: the Urban Land Institute, 2015. ISBN: 978-0-87420-370-7 Returns on Resilience THE BUSINESS CASE Project Director and Author Sarene Marshall Primary Author Kathleen McCormick This report was made possible through the generous support of The Kresge Foundation. Center for Sustainability About the Urban Land Institute The mission of the Urban Land Institute is to provide leadership in the responsible use of land and in creating and sustaining thriving communities worldwide. Established in 1936, the Institute today has more than 35,000 members worldwide representing the entire spectrum of the land use and development disciplines. ULI relies heavily on the experience of its members. It is through member involvement and information resources that ULI has been able to set standards of excellence in development practice. The Institute has long been recognized as one of the world’s most respected and widely quoted sources of objective information on urban planning, growth, and development. ULI SENIOR -

Miami Cbd Large Blocks of Office Space

RESEARCH MIAMI CBD AUGUST 2019 LARGE BLOCKS OF OFFICE SPACE 836 MACARTHUR CAUSEWAY 100,000+ SF Blocks 395 Southeast Financial Center Four Seasons Tower 200 S Biscayne Boulevard 1441 Brickell Avenue Ponte Gadea USA 9 Millennium Partners Management 1 1,225,000 RBA – 67.8% Leased 258,767 RBA – 98.1% Leased 133,120 SF Max Contig. 28,763 SF Max Contig. $53.25/RSF FS $60.00/RSF FS Citigroup Center 1221 Brickell 201 S Biscayne Boulevard 1221 Brickell Avenue Crocker Partners Rockpoint Group 2 809,594 RBA – 74.0% Leased 10 408,649 RBA – 86.1% Leased 95 127,634 SF Max Contig. 26,761 SF Max Contig. $48.00-$52.00/RSF FS $52.50/RSF FS Freedom PORT BLVD A1A Tower Wells Fargo Center 50,000 - 99,999 SF Blocks 333 SE 2nd Avenue AVE MetLife Real Estate Investments AVE 11 ND 752,845 RBA – 85.9% Leased ND SunTrust International Center 26,000 SF Max Contig. 1 SE 3rd Avenue BISCAYNE BLVD BISCAYNE $48.00/RSF FS N MIAMI AVE MIAMI N 2 NE NW 2 NW MiaMarina Pacific Coast Capital Partners MIAMI RIVER 3 440,299 RBA – 66.4% Leased 90,255 SF Max Contig. $38.00-$40.00/RSF FS 15,000 - 24,999 SF Blocks Brickell Office Plaza Brickell World Plaza Downtown 777 Brickell Avenue 600 Brickell Avenue 8 Padua Realty Company Elm Spring, Inc. 4 288,457 RBA – 74.8% Leased 12 631,866 RBA – 92.5% Leased 3 6 68,386 SF Max Contig. CLASS 24,138 SF Max Contig. -

1450 BRICKELL FACTS Large Missile

At the entrance MIAMI · FLORIDA to the Brickell Setting the5415, 5455Highest Standard in Class A Office Buildings Financial District, 1450 Brickell offers Class A corporate headquarters prominence with panoramic water views, commuter convenience and unparalleled infrastructure for business continuity. 1450BRICKELL.COM 5415, 5455 SETTING THE HIGHEST STANDARD 1450 Brickell is a 35-story, 626,750 RSF Class A Office High Rise Tower at the entrance to Brickell Avenue 1450BRICKELL.COM 5415, 5455 CONVENIENT ACCESS AWAY FROM NEAR TOP HOTELS, RESTAURANTS, TRAFFIC CONGESTION OF DRAWBRIDGES RESIDENTIAL, AND RETAIL Brickell Ave. 18 th SW 7 St. Exit 1-B Brickell Key SW 8th St. S. Miami Ave. B I 15 17 Brickell Key SW 7th Ave. Metromover SW 2nd Ave. S. Miami Ave. 16 H SW 11th St. SW 1th Ave. Brickell City Center SW 8th St. 13 Brickell Ave. SW 9th Ave. 12 11 15th Rd. Metromover Shops At Mary Brickell Village 14 C SW 10th St. F G Coral Way 10 Simpson th SW 26 Rd. Park 9 SW 12th St. D S. Miami Ave. 8 S. Miami Ave. SW 15th Rd. 7 S. Miami Ave. th 5415, 5455 SW 12 Ave. 6 C 5 Exit 1-A A 4 Brickell Ave. 3 I Simpson 2 Park Coral Way 1 U.S. 1 Brickell Hammock S. Miami Ave. E Alice C. Wainwright 5415, 5455 5415, 5455 LESS DRIVE TIME... MORE BUSINESS 1. Echo Brickell Residences 9. JW Marriot A. From Brickell Avenue F. From S.W. 15th Road 2. PM Fish & Steak House 10. Nusr-Et Steakhouse going North G. -

Miami Office Market Report

FIRST QUARTER 2018 MIAMI OFFICE MARKET REPORT Licensed Real Estate Broker BLANCA COMMERCIAL REAL ESTATE | 1ST QUARTER 2018 MARKET REPORT | PAGE 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY DOWNTOWN | BRICKELL | CORAL GABLES | MIAMI AIRPORT As of first quarter 2018, favorable local and national economic Class A product remains robust. Highly populated suburban markets conditions, coupled with Miami’s continued global appeal, helped with abundant amenities and single-digit vacancies, such as Aventura sustain the success of Miami’s vibrant office market. The latest and Coconut Grove, have more than 350,000 square feet of office data demonstrate the continued decline of Miami-Dade County’s space delivering in the next 18 to 24 months The evolution of new unemployment rate (currently at 4.7%) with more than 30,000 jobs office submarkets like Wynwood, with its growing residential and added over the past year. The county also recorded 4.5% GDP vibrant amenity base, now able to offer Class A office product, poised growth, signaling a positive outlook for companies with an established to attract a new wave of companies looking to establish their offices in presence in Miami. Year-over-year, robust leasing activity and steady a creative and culturally driven office market. increase in rents evidence the demand for premium Class A office space, a trend we can expect to continue this year. With the first quarter showing local economic stability, a significant number of tenants (more than 900,000 square feet) in the market, and Year-over-year, the Miami Class A office market closed more than 1.8 limited new supply, we expect solid performance in the office sector million square feet of office lease transactions, and is outperforming this year. -

Miami DDA Area Offices

NE 28th St NE 27th Te NW 28th St NE 27th St NW 27th St NE 26th Te No. Class Name Address Year RBA 1 A 10 Museum Park 1040 Biscayne Blvd 2007 24,000 \ NW 26th St NE 26th St 2 A 900 Biscayne Bay 900 Biscayne Blvd 2008 95,000 3 A Marina Blue 888 Biscayne Blvd 2008 750,000 4 B NAP of the Americas 50 NE 9th ST 2001 750,000 NW 25th St NE 25th St 5 A 2 MiamiCentral 601 NW 1st Ave 2018 190,000 NE 24th St 6 A 3 MiamiCentral 161 NW 6th ST 2018 95,000 NW 24th St NW 24th St NE 24th St 7 B The Citadel 49 NW 5th ST 1950 50,000 8 B Courthouse Center 40 NW 3rd ST 2009 40,300 NW 23rd St NW 23rd St 9 B 36 NE 2nd ST 36 NE 2nd ST 1925 205,172 10 B Chase Bank Building 150 SE 2nd Ave 1966 125,388 NE 23rd St NE 22nd Te 11 B Bayside Office Center 141 NE 3rd Ave 1923 57,093 12 B 261 Office Lofts 261 NE 1st ST 1982 34,741 NE 22nd St 13 B New World Tower 100 N Biscayne Blvd 1966 285,000 NW 22nd St Ave 2nd NE 14 C Capital Building 117 NE 1st Ave 1926 85,000 15 C Congress Building 111 NE 2nd Ave 1922 242,294 NE 21st St Dade Commonwealth 16 B Building 139 NE 1st ST 1927 43,265 17 B One Bayfront Plaza 100 S Biscayne Blvd 1959 312,896 BISCAYNE BOULEVARD BISCAYNE Flagler Federal NE 20th St 18 B Building 101-111 NE 1st ST 1961 64,470 N MIAMI AVE MIAMI N NW Miami Ct Miami NW NW 1st Ave 1st NW NW 2nd Ave 2nd NW NE 19th Te NW 1st Ct 1st NW NW 20th St Pl 1st NW 19 B Historic Post Office 100 NE 1st Ave 1912 37,600 20 B Metromall Building 1 Ne 1st ST 1926 156,000 NE 19th St 21 C 219-223 E Flagler ST 219-223 E Flagler ST 1984 42,000 22 B A.I. -

A Brickell Avenue Address British Glamour

A Brickell Avenue address Britishfused Glamour. with Proudly one of the few LEED buildings on Brickell. be the first... Rendering is an artist conception only. BRICKELL CITYCENTRE MARY BRICKELL VILLAGE METRO MOVER / METRORAIL Rendering is an artist conception only. MIAMI ART MUSEUM, MUSEUM PARK AMERICAN AIRLINES ARENA THE CHARM OF A NEIGHBORHOOD / THE SOPHISTICATION OF AN URBAN CENTER / A NEW URBAN CITYCENTRE THAT CHANGES THE LANDSCAPE OF BRICKELL cosmopolitan AND MIAMI / FINE DINING AND CASUAL DINING WITHIN STEPS / COOL OCEAN BREEZES THAT NAVIGATE BETWEEN BUILDINGS ONLY TO FIND YOU / BRICKELL KEY a completely new energy and sophistication for Miami BEACH / ART GALLERIES AND ART WALKS / FARMER’S MARKETS WITH THE FRESHES OF FRUITS AND VEGETABLES / L.A. FITNESS AND OTHER GREAT GYMS / THE FOUR SEASONS HOTEL / MICHAEL’S GENUINE / CHIC HOTELS WITHIN MINUTES INCLUDING THE NEW SLS HOTEL / YOUNG PROFESSIONALS WHO LIKE TO SEE AND ADRIENNE ARSHT CENTER FROST SCIENCE MUSEUM BE SEEN / MEET ON THE STREET OR IN A WINE BAR / DO YOUR BUSINESS DURING THE DAY ON BRICKELL AVENUE / PLAY ON SOUTH MIAMI AVENUE / DANCE TO THE ELECTRONIC BEATS OF SEGAFREDO OR THE COLOMBIAN ANTHEMS AT BARU / WHY NOT BREAK FOR LUNCH AT THE WORLD-FAMOUS CIPRIANANI / ARRIVE ON BOAT OR TAKE A CAB - THIS IS URBAN LIVING / LAUGHTER CAN BE HEARD AT THE STEPS OF MOST GREAT EATERYS / SOLITUDE IS INSIDE YOUR RESIDENCE / RELAX & BREATHE“More / THE than CHARM OFa Aprestigious NEIGHBORHOOD / THEaddress, SOPHISTICATION The OF Bond AN URBAN puts CENTER you / A NEW at URBAN the CITICENTRE center THAT of CHANGESa THE LAND- SCAPE OF BRICKELL AND MIAMI / FINE DINING AND CASUAL DINING WITHIN STEPS / COOL OCEAN BREEZES THAT NAVIGATE BETWEEN BUILDINGS ONLY TO FIND YOU / BRICKELLneighborhood KEY BEACH / ART GALLERIES bustling AND ART with WALKS /new FARMER’S vibrant MARKETS WITH restaurants, THE FRESHES OF FRUITS luxury AND VEGETABLES shopping, / L.A. -

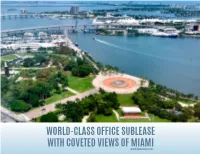

World-Class Office Sublease with Coveted Views Of

WORLD-CLASS OFFICE SUBLEASE WITH COVETED VIEWS OF www.blancacre.comMIAMI 2 SUBLEASE @ SOUTHEAST FINANCIAL CENTER FACTS + FEATURES yTHE SUBLEASE offers timeless, high-end finishes in a world-class setting with coveted views of Miami. 22,822 RSF | 33rd Floor | Full Floor Elevator lobby exposure Term expires March 31, 2026 Furniture is negotiable (artwork not included) Perimeter offices with views COVID-19 engineering controls in place Cat 6 wiring Voice over IP phone system UPS system that powers server room Lease rate available upon request Layout includes: 1 Presidential office suite with private rest room 1 Executive reception / greeting area 28 Executive offices (10 window offices) 37 Workstation 5 Conference rooms 1 Training room J 1 Employee lounge VIDEO TOUR 1 Kitchen Reception area with elevator lobby exposure views of miami www.blancacre.com 3 SUBLEASE @ SOUTHEAST FINANCIAL CENTER move in ready PHOTOS Reception with Elevator Lobby Exposure Super-sized Conference Room / Training Room Employee Kitchen Turnkey Class A Office Space Available Immediately Workstations with Privacy Walls Conference Room Executive Office Greeting Area www.blancacre.com 4 SUBLEASE @ SOUTHEAST FINANCIAL CENTER PHOTOS Executive Office C-Suite Office with Private Restroom Media Huddle Room Huddle Area Executive Area Reception www.blancacre.com 5 SUBLEASE @ SOUTHEAST FINANCIAL CENTER VIEWS J www.blancacre.com VIDEO TOUR 6 SUBLEASE @ SOUTHEAST FINANCIAL CENTER FLOOR PLAN c= r=== r== 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 F.E. 0 0 0 0 0 F.E. F.E. 0 0 0 D c= == == (l LJ □□ �o�□�,1-�o�o� 00 00 00 00 I I I I I I I - □ "' Q Q Q Q 1=J' Q Q Q Q (l □ I I I \ I I LJ LJ LJ LJ L L u g \ �y - - � LJ LJ ' / □ LJ F.E.* L I ! llt-1---J>-+--< LJ LJ f"t,, - □[] \d) = □ -\ \ (l Cl '=====c-"L,, I�( N LJ LJ I - ! . -

YAI Talks # Miami Conquering New Grounds: the Finance and Banking Industry

YAI Talks # Miami Conquering New Grounds: The Finance and Banking Industry YAI Talks # Miami Overview Conquering New Grounds: Presented by the ITA Young Arbitrators Initiative (YAI) YAI TALKS # is a series of local events presenting talks, workshops The Finance and Banking Industry or interviews that cover a wide range of subjects relating to arbitration, designed for learning, provoking conversation and February 24, 2017 sharing knowledge and experiences among young practitioners. White & Case LLP Registration is free! cailaw.org/ita Southeast Financial Center 200 South Biscayne Boulevard Miami, Florida, USA Co-Sponsored by Future of ITA is an Institute of Arbitration Miami YAI Talks # Miami SCHEDULE February 24 The finance and banking industry is a trending topic these days given the recent ITA YAI Co-Chairs publication of the ICC Commission Report on Financial Institutions and International Arbitration. This event aims to provide young arbitration stakeholders with a legal Montserrat Manzano and market-oriented perspective on the challenges posed by the development of Von Wobeser y Sierra, S.C. arbitration in the finance and banking industry, focusing in particular in the role of Mexico City, Mexico the region. YAI TALKS # is a series of local events presenting talks, workshops or interviews Silvia Marchili that cover a wide range of subjects relating to arbitration, designed for learning, King & Spalding LLP provoking conversation and sharing knowledge and experiences among young practitioners. Houston, Texas Thanks to the generosity of our sponsors, this event is tuition-free and includes brunch. Please register in advance at cailaw.org/ita to help us capture an accurate headcount. -

1401 Brickell Ave. | Miami

1401 Brickell Ave. | Miami Partnership. Performance. ONE OF A KIND REDEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY ON BRICKELL AVENUE Avison Young is pleased to exclusively offer for sale 1401 Brickell Avenue, a 188,138 SF office building situated on 2.02 acres of land (also stated elsewhere as 87,958 sf) in Miami’s most prestigious financial district. This class B building in a class A infill development location provides strong in place cash flow for a developer, with great density according to Miami 21 zoning. 1401 Brickell is located on the east side of the street between two of the best-known buildings of the corridor, Four Seasons and Brickell Arch (aka, Espirito Santo Plaza), which positions it well within this Live, Work and Play neighborhood. This area continues to grow and has become the dense, high-rise core of Miami’s banking, investment, and financial sectors, and is filled with luxury condominium and apartment towers, upscale restaurants and entertainment venues. 1401 Brickell has excellent ingress and egress from the north, south and west and is within easy access to I-95, US 1, downtown Miami, and all public transportation. The current zoning at the property is T6-48A-O which allows for much more than the current 188,138 SF of office use, with over 1,000 residential units, up to 80 stories and a total of 1.45 million square feet of development possible. T6-48A-O zoning gives a developer the opportunity to utilize residential, office, hotel and retail uses to a create the project they envision. The property is being marketed with no asking price. -

The FUTURE IS BRIGHT in DOWNTOWN MIAMI TRANSFORM | CONNECT | CREATE Two Miamicentral

MIAMICENTRAL The FUTURE IS BRIGHT IN DOWNTOWN MIAMI TRANSFORM | CONNECT | CREATE Two MiamiCentral TRANSFORM 700 MiamiCentral MIAMICENTRAL INTERSTATE MiamiCentral is an 11-acre development in Downtown Miami featuring unique office, retail and residential space in the region’s only transportation hub. The development will transform downtown Miami with 4 million square feet of new development. TRANSFORMING THE MEANING OF ACCESS PROJECT FEATURES 800,000 SF of Class A Office Space 200,000 SF of Retail Space 1,180 Residential Units TRANSFORM | CONNECT | CREATE MIAMICENTRAL | PAGE 1 CONNECTIVITY Connectivity throughout Miami-Dade County, and to key cities in South Florida and Orlando. Connectivity to a global marketplace with unmatched accessibility to Miami International Airport (estimated 12 minutes from MiamiCentral to Miami International Airport). TRANSFORMING Connectivity to all means of public transportation including but not limited to Metrorail, Metromover and Tri Rail. THE MEANING IT Redundant fiber optic infrastructure between MiamiCentral OF INNOVATION and direct connection to the NAP (network access point) of the Americas in Miami, deliver cost-effective and unmatched fast access and redundancy for tenants. Seamless scalability Campus-wide WiFi throughout MiamiCentral. A digital antenna system (DAS) providing tenants and MIAMICENTRAL visitors with maximum service State-of-the-art connectivity Sophisticated IT infrastructure EFFICIENCY Designed with large, open floor plates that feature a Efficient structure and design compact core to allow for maximum workplace layout Column-free, generous, clear spans to accommodate higher density, connectivity and collaboration Bay depth and configuration designed to allow for increased capacity to maximize workstations and employee headcount Slab-to-Slab height to allow flexibility in ceiling heights that can be varied to accommodate space programming Floor-to-ceiling windows that provide enhanced natural light TRANSFORM | CONNECT | CREATE MIAMICENTRAL | PAGE 2 FROM MIAMI YOU CONNECT TO .. -

Year-End Wrap up What to Know About Real Estate Going Into 2016

MIAMI OFFICE MARKET YEAR-END WRAP UP WHAT TO KNOW ABOUT REAL ESTATE GOING INTO 2016 CBD SURGE RATES CONTINUE TO RISE CORAL GABLES – THE COMEBACK ELEVATED OCCUPANCIES, RATES AND ACQUISITIONS MIAMI AIRPORT READIES FOR NEW SUPPLY EXTREMELY LOW CLASS A VACANCY REAL ESTATE OUTLOOK 4Q -2015 2015 REAL ESTATE OUTLOOK 4Q MIAMI OFFICE MARKET FOURTH QUARTER 2015 Encouraging market fundamentals boost investor and landlord confidence with elevated acquisitions and persistent rental rate hikes Near term for-lease office construction remains relatively restrained – with pre-leasing reported in most buildings ECONOMY Miami’s office using industry sectors ended 2015 with positive gains OFFICE TRENDS - OVERALL MARKET On the national front, 2015’s underlying data remained generally strong – despite 8.0 YEARS CURRENT QUARTER long term wage stagnation, both lower and higher paying jobs are coming back. VACANCY U.S. jobs data showed good pick up in hiring - Professional/Business Services, Healthcare, Construction and Restaurant/Bar industries – essential South Florida 12.5% sectors. Overall labor force participation in the nation was just over 60%+, up from 8-year low in supply previous decades due in large part to demographics i.e. aging population. levels ABSORPTION Both the state and the region continue to attract residents with population growth in the three-county South Florida market among the fastest-growing in Florida. 804,862 SF Unemployment in the Miami metro was back to early 2015’s 5.5% and down from YTD 2015 most of the monthly 6.0+% rates posted during the year - still among the lowest Six consecutive years of since midyear 2008.