Identifying Highly Penetrant Disease Causal Mutations Using Next Generation Sequencing: Guide to Whole Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Synergistic Genetic Interactions Between Pkhd1 and Pkd1 Result in an ARPKD-Like Phenotype in Murine Models

BASIC RESEARCH www.jasn.org Synergistic Genetic Interactions between Pkhd1 and Pkd1 Result in an ARPKD-Like Phenotype in Murine Models Rory J. Olson,1 Katharina Hopp ,2 Harrison Wells,3 Jessica M. Smith,3 Jessica Furtado,1,4 Megan M. Constans,3 Diana L. Escobar,3 Aron M. Geurts,5 Vicente E. Torres,3 and Peter C. Harris 1,3 Due to the number of contributing authors, the affiliations are listed at the end of this article. ABSTRACT Background Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD) and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) are genetically distinct, with ADPKD usually caused by the genes PKD1 or PKD2 (encoding polycystin-1 and polycystin-2, respectively) and ARPKD caused by PKHD1 (encoding fibrocys- tin/polyductin [FPC]). Primary cilia have been considered central to PKD pathogenesis due to protein localization and common cystic phenotypes in syndromic ciliopathies, but their relevance is questioned in the simple PKDs. ARPKD’s mild phenotype in murine models versus in humans has hampered investi- gating its pathogenesis. Methods To study the interaction between Pkhd1 and Pkd1, including dosage effects on the phenotype, we generated digenic mouse and rat models and characterized and compared digenic, monogenic, and wild-type phenotypes. Results The genetic interaction was synergistic in both species, with digenic animals exhibiting pheno- types of rapidly progressive PKD and early lethality resembling classic ARPKD. Genetic interaction be- tween Pkhd1 and Pkd1 depended on dosage in the digenic murine models, with no significant enhancement of the monogenic phenotype until a threshold of reduced expression at the second locus was breached. -

Supplemental Information

Supplemental information Dissection of the genomic structure of the miR-183/96/182 gene. Previously, we showed that the miR-183/96/182 cluster is an intergenic miRNA cluster, located in a ~60-kb interval between the genes encoding nuclear respiratory factor-1 (Nrf1) and ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2H (Ube2h) on mouse chr6qA3.3 (1). To start to uncover the genomic structure of the miR- 183/96/182 gene, we first studied genomic features around miR-183/96/182 in the UCSC genome browser (http://genome.UCSC.edu/), and identified two CpG islands 3.4-6.5 kb 5’ of pre-miR-183, the most 5’ miRNA of the cluster (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1 and Seq. S1). A cDNA clone, AK044220, located at 3.2-4.6 kb 5’ to pre-miR-183, encompasses the second CpG island (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1). We hypothesized that this cDNA clone was derived from 5’ exon(s) of the primary transcript of the miR-183/96/182 gene, as CpG islands are often associated with promoters (2). Supporting this hypothesis, multiple expressed sequences detected by gene-trap clones, including clone D016D06 (3, 4), were co-localized with the cDNA clone AK044220 (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1). Clone D016D06, deposited by the German GeneTrap Consortium (GGTC) (http://tikus.gsf.de) (3, 4), was derived from insertion of a retroviral construct, rFlpROSAβgeo in 129S2 ES cells (Fig. 1A and C). The rFlpROSAβgeo construct carries a promoterless reporter gene, the β−geo cassette - an in-frame fusion of the β-galactosidase and neomycin resistance (Neor) gene (5), with a splicing acceptor (SA) immediately upstream, and a polyA signal downstream of the β−geo cassette (Fig. -

Variation in Protein Coding Genes Identifies Information

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/679456; this version posted June 21, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Animal complexity and information flow 1 1 2 3 4 5 Variation in protein coding genes identifies information flow as a contributor to 6 animal complexity 7 8 Jack Dean, Daniela Lopes Cardoso and Colin Sharpe* 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Institute of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 25 School of Biological Science 26 University of Portsmouth, 27 Portsmouth, UK 28 PO16 7YH 29 30 * Author for correspondence 31 [email protected] 32 33 Orcid numbers: 34 DLC: 0000-0003-2683-1745 35 CS: 0000-0002-5022-0840 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 Abstract bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/679456; this version posted June 21, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Animal complexity and information flow 2 1 Across the metazoans there is a trend towards greater organismal complexity. How 2 complexity is generated, however, is uncertain. Since C.elegans and humans have 3 approximately the same number of genes, the explanation will depend on how genes are 4 used, rather than their absolute number. -

Genetic Background of Ataxia in Children Younger Than 5 Years in Finland E444

Volume 6, Number 4, August 2020 Neurology.org/NG A peer-reviewed clinical and translational neurology open access journal ARTICLE Genetic background of ataxia in children younger than 5 years in Finland e444 ARTICLE Cerebral arteriopathy associated with heterozygous variants in the casitas B-lineage lymphoma gene e448 ARTICLE Somatic SLC35A2 mosaicism correlates with clinical fi ndings in epilepsy brain tissuee460 ARTICLE Synonymous variants associated with Alzheimer disease in multiplex families e450 Academy Officers Neurology® is a registered trademark of the American Academy of Neurology (registration valid in the United States). James C. Stevens, MD, FAAN, President Neurology® Genetics (eISSN 2376-7839) is an open access journal published Orly Avitzur, MD, MBA, FAAN, President Elect online for the American Academy of Neurology, 201 Chicago Avenue, Ann H. Tilton, MD, FAAN, Vice President Minneapolis, MN 55415, by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. at 14700 Citicorp Drive, Bldg. 3, Hagerstown, MD 21742. Business offices are located at Two Carlayne E. Jackson, MD, FAAN, Secretary Commerce Square, 2001 Market Street, Philadelphia, PA 19103. Production offices are located at 351 West Camden Street, Baltimore, MD 21201-2436. Janis M. Miyasaki, MD, MEd, FRCPC, FAAN, Treasurer © 2020 American Academy of Neurology. Ralph L. Sacco, MD, MS, FAAN, Past President Neurology® Genetics is an official journal of the American Academy of Neurology. Journal website: Neurology.org/ng, AAN website: AAN.com CEO, American Academy of Neurology Copyright and Permission Information: Please go to the journal website (www.neurology.org/ng) and click the Permissions tab for the relevant Mary E. Post, MBA, CAE article. Alternatively, send an email to [email protected]. -

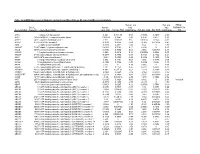

Nº Ref Uniprot Proteína Péptidos Identificados Por MS/MS 1 P01024

Document downloaded from http://www.elsevier.es, day 26/09/2021. This copy is for personal use. Any transmission of this document by any media or format is strictly prohibited. Nº Ref Uniprot Proteína Péptidos identificados 1 P01024 CO3_HUMAN Complement C3 OS=Homo sapiens GN=C3 PE=1 SV=2 por 162MS/MS 2 P02751 FINC_HUMAN Fibronectin OS=Homo sapiens GN=FN1 PE=1 SV=4 131 3 P01023 A2MG_HUMAN Alpha-2-macroglobulin OS=Homo sapiens GN=A2M PE=1 SV=3 128 4 P0C0L4 CO4A_HUMAN Complement C4-A OS=Homo sapiens GN=C4A PE=1 SV=1 95 5 P04275 VWF_HUMAN von Willebrand factor OS=Homo sapiens GN=VWF PE=1 SV=4 81 6 P02675 FIBB_HUMAN Fibrinogen beta chain OS=Homo sapiens GN=FGB PE=1 SV=2 78 7 P01031 CO5_HUMAN Complement C5 OS=Homo sapiens GN=C5 PE=1 SV=4 66 8 P02768 ALBU_HUMAN Serum albumin OS=Homo sapiens GN=ALB PE=1 SV=2 66 9 P00450 CERU_HUMAN Ceruloplasmin OS=Homo sapiens GN=CP PE=1 SV=1 64 10 P02671 FIBA_HUMAN Fibrinogen alpha chain OS=Homo sapiens GN=FGA PE=1 SV=2 58 11 P08603 CFAH_HUMAN Complement factor H OS=Homo sapiens GN=CFH PE=1 SV=4 56 12 P02787 TRFE_HUMAN Serotransferrin OS=Homo sapiens GN=TF PE=1 SV=3 54 13 P00747 PLMN_HUMAN Plasminogen OS=Homo sapiens GN=PLG PE=1 SV=2 48 14 P02679 FIBG_HUMAN Fibrinogen gamma chain OS=Homo sapiens GN=FGG PE=1 SV=3 47 15 P01871 IGHM_HUMAN Ig mu chain C region OS=Homo sapiens GN=IGHM PE=1 SV=3 41 16 P04003 C4BPA_HUMAN C4b-binding protein alpha chain OS=Homo sapiens GN=C4BPA PE=1 SV=2 37 17 Q9Y6R7 FCGBP_HUMAN IgGFc-binding protein OS=Homo sapiens GN=FCGBP PE=1 SV=3 30 18 O43866 CD5L_HUMAN CD5 antigen-like OS=Homo -

Table S1. PCD Genes Analysed from the Multi-Gene Panel. Gene Names

Supplementary material J Med Genet Table S1. PCD genes analysed from the multi-gene panel. Gene ID Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) defects Genomic Interval # exons ARMC4 ODA chr10:28089736-28284096 22 CFAP298/C21ORF59 ODA+IDA chr21:33951107-33984578 10 CCDC103 ODA+IDA chr17:42978342-42980210 3 CCDC114 ODA chr19:48800208-48822053 13 CCDC151 ODA chr19:11531478-11546617 16 CCDC39 MT disorganised+IDA chr3:180331609-180466094 24 CCDC40 MT disorganised+IDA chr17:78010437-78073599 24 CCDC65 MT disorganised/sub-TEM defect chr12:49298095-49325285 9 CCNO Reduced cilia numbers chr5:54527178-54529376 3 DNAAF1 ODA+IDA chr16:84179021-84212037 15 DNAAF2 ODA+IDA chr14:50092235-50101892 3 DNAAF3 ODA+IDA chr19:55670405-55678041 12 DNAAF5 ODA+IDA chr7:766333-825315 13 DNAH11 Normal (sub-TEM defect) chr7:21582839-21940897 85 DNAH5 ODA chr5:13692068-13944572 79 DNAI1 ODA chr9:34458979-34520779 21 DNAI2 ODA chr17:72277761-72310380 12 DNAJB13 CP chr11:73662090-73681184 8 DNAL1 ODA chr14:74111718-74162670 8 DRC1 MT disorganised/sub-TEM defect chr2:26624833-26679410 19 DYX1C1 ODA+IDA chr15:55710208-55790552 10 GAS8 Normal (sub-TEM defect) chr16:90089105-90109778 11 HYDIN CP/sub-TEM defect chr16:70841458-71264615 90 LRRC6 ODA+IDA chr8:133584529-133687764 15 MCIDAS Reduced cilia numbers chr5:54516169-54522991 7 NME8 ODA chr7:37889844-37936719 15 OFD1 Not published chrX:13753166-13787252 24 PIH1D3 ODA+IDA chrX:106456081-106486553 6 RPGR Mixed chrX:38128854-38186645 20 RSPH1 CP chr21:43892903-43916321 9 RSPH3 CP chr6:159398545-159421033 8 RSPH4A CP chr6:116937762-116953629 6 RSPH9 CP chr6:43612811-43640212 7 SPAG1 ODA+IDA chr8:101174484-101253275 18 STK36 CP/sub-TEM defect chr2:219537528-219566757 28 TTC25 ODA chr17:40086952-40117526 11 ZMYND10 ODA+IDA chr3:50378816-50383035 12 Gene names according to HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee. -

MAFB Determines Human Macrophage Anti-Inflammatory

MAFB Determines Human Macrophage Anti-Inflammatory Polarization: Relevance for the Pathogenic Mechanisms Operating in Multicentric Carpotarsal Osteolysis This information is current as of October 4, 2021. Víctor D. Cuevas, Laura Anta, Rafael Samaniego, Emmanuel Orta-Zavalza, Juan Vladimir de la Rosa, Geneviève Baujat, Ángeles Domínguez-Soto, Paloma Sánchez-Mateos, María M. Escribese, Antonio Castrillo, Valérie Cormier-Daire, Miguel A. Vega and Ángel L. Corbí Downloaded from J Immunol 2017; 198:2070-2081; Prepublished online 16 January 2017; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601667 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/198/5/2070 http://www.jimmunol.org/ Supplementary http://www.jimmunol.org/content/suppl/2017/01/15/jimmunol.160166 Material 7.DCSupplemental References This article cites 69 articles, 22 of which you can access for free at: http://www.jimmunol.org/content/198/5/2070.full#ref-list-1 by guest on October 4, 2021 Why The JI? Submit online. • Rapid Reviews! 30 days* from submission to initial decision • No Triage! Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists • Fast Publication! 4 weeks from acceptance to publication *average Subscription Information about subscribing to The Journal of Immunology is online at: http://jimmunol.org/subscription Permissions Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts The Journal of Immunology is published twice each month by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2017 by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. -

HHS Public Access Author Manuscript

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author Manuscript Author ManuscriptNature. Author ManuscriptAuthor manuscript; Author Manuscript available in PMC 2015 November 28. Published in final edited form as: Nature. 2015 May 28; 521(7553): 520–524. doi:10.1038/nature14269. Global genetic analysis in mice unveils central role for cilia in congenital heart disease You Li1,8, Nikolai T. Klena1,8, George C Gabriel1,8, Xiaoqin Liu1,7, Andrew J. Kim1, Kristi Lemke1, Yu Chen1, Bishwanath Chatterjee1, William Devine2, Rama Rao Damerla1, Chien- fu Chang1, Hisato Yagi1, Jovenal T. San Agustin5, Mohamed Thahir3,4, Shane Anderton1, Caroline Lawhead1, Anita Vescovi1, Herbert Pratt5, Judy Morgan6, Leslie Haynes6, Cynthia L. Smith6, Janan T. Eppig6, Laura Reinholdt6, Richard Francis1, Linda Leatherbury7, Madhavi K. Ganapathiraju3,4, Kimimasa Tobita1, Gregory J. Pazour5, and Cecilia W. Lo1,9 1Department of Developmental Biology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA 2Department of Pathology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA 3Department of Biomedical Informatics, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA 4Intelligent Systems Program, School of Arts and Sciences, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 9Corresponding author. [email protected] Phone: 412-692-9901, Mailing address: Dept of Developmental Biology, Rangos Research Center, 530 45th St, Pittsburgh, PA, 15201. 8Co-first authors Author Contributions: Study design: CWL ENU mutagenesis, line cryopreservation, JAX strain datasheet construction: -

Transcriptional Profile of Human Anti-Inflamatory Macrophages Under Homeostatic, Activating and Pathological Conditions

UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS QUÍMICAS Departamento de Bioquímica y Biología Molecular I TESIS DOCTORAL Transcriptional profile of human anti-inflamatory macrophages under homeostatic, activating and pathological conditions Perfil transcripcional de macrófagos antiinflamatorios humanos en condiciones de homeostasis, activación y patológicas MEMORIA PARA OPTAR AL GRADO DE DOCTOR PRESENTADA POR Víctor Delgado Cuevas Directores María Marta Escribese Alonso Ángel Luís Corbí López Madrid, 2017 © Víctor Delgado Cuevas, 2016 Universidad Complutense de Madrid Facultad de Ciencias Químicas Dpto. de Bioquímica y Biología Molecular I TRANSCRIPTIONAL PROFILE OF HUMAN ANTI-INFLAMMATORY MACROPHAGES UNDER HOMEOSTATIC, ACTIVATING AND PATHOLOGICAL CONDITIONS Perfil transcripcional de macrófagos antiinflamatorios humanos en condiciones de homeostasis, activación y patológicas. Víctor Delgado Cuevas Tesis Doctoral Madrid 2016 Universidad Complutense de Madrid Facultad de Ciencias Químicas Dpto. de Bioquímica y Biología Molecular I TRANSCRIPTIONAL PROFILE OF HUMAN ANTI-INFLAMMATORY MACROPHAGES UNDER HOMEOSTATIC, ACTIVATING AND PATHOLOGICAL CONDITIONS Perfil transcripcional de macrófagos antiinflamatorios humanos en condiciones de homeostasis, activación y patológicas. Este trabajo ha sido realizado por Víctor Delgado Cuevas para optar al grado de Doctor en el Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas de Madrid (CSIC), bajo la dirección de la Dra. María Marta Escribese Alonso y el Dr. Ángel Luís Corbí López Fdo. Dra. María Marta Escribese -

Mrna Expression in Human Leiomyoma and Eker Rats As Measured by Microarray Analysis

Table 3S: mRNA Expression in Human Leiomyoma and Eker Rats as Measured by Microarray Analysis Human_avg Rat_avg_ PENG_ Entrez. Human_ log2_ log2_ RAPAMYCIN Gene.Symbol Gene.ID Gene Description avg_tstat Human_FDR foldChange Rat_avg_tstat Rat_FDR foldChange _DN A1BG 1 alpha-1-B glycoprotein 4.982 9.52E-05 0.68 -0.8346 0.4639 -0.38 A1CF 29974 APOBEC1 complementation factor -0.08024 0.9541 -0.02 0.9141 0.421 0.10 A2BP1 54715 ataxin 2-binding protein 1 2.811 0.01093 0.65 0.07114 0.954 -0.01 A2LD1 87769 AIG2-like domain 1 -0.3033 0.8056 -0.09 -3.365 0.005704 -0.42 A2M 2 alpha-2-macroglobulin -0.8113 0.4691 -0.03 6.02 0 1.75 A4GALT 53947 alpha 1,4-galactosyltransferase 0.4383 0.7128 0.11 6.304 0 2.30 AACS 65985 acetoacetyl-CoA synthetase 0.3595 0.7664 0.03 3.534 0.00388 0.38 AADAC 13 arylacetamide deacetylase (esterase) 0.569 0.6216 0.16 0.005588 0.9968 0.00 AADAT 51166 aminoadipate aminotransferase -0.9577 0.3876 -0.11 0.8123 0.4752 0.24 AAK1 22848 AP2 associated kinase 1 -1.261 0.2505 -0.25 0.8232 0.4689 0.12 AAMP 14 angio-associated, migratory cell protein 0.873 0.4351 0.07 1.656 0.1476 0.06 AANAT 15 arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase -0.3998 0.7394 -0.08 0.8486 0.456 0.18 AARS 16 alanyl-tRNA synthetase 5.517 0 0.34 8.616 0 0.69 AARS2 57505 alanyl-tRNA synthetase 2, mitochondrial (putative) 1.701 0.1158 0.35 0.5011 0.6622 0.07 AARSD1 80755 alanyl-tRNA synthetase domain containing 1 4.403 9.52E-05 0.52 1.279 0.2609 0.13 AASDH 132949 aminoadipate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase -0.8921 0.4247 -0.12 -2.564 0.02993 -0.32 AASDHPPT 60496 aminoadipate-semialdehyde -

Signatures of Adaptive Evolution in Platyrrhine Primate Genomes 5 6 Hazel Byrne*, Timothy H

1 2 Supplementary Materials for 3 4 Signatures of adaptive evolution in platyrrhine primate genomes 5 6 Hazel Byrne*, Timothy H. Webster, Sarah F. Brosnan, Patrícia Izar, Jessica W. Lynch 7 *Corresponding author. Email [email protected] 8 9 10 This PDF file includes: 11 Section 1: Extended methods & results: Robust capuchin reference genome 12 Section 2: Extended methods & results: Signatures of selection in platyrrhine genomes 13 Section 3: Extended results: Robust capuchins (Sapajus; H1) positive selection results 14 Section 4: Extended results: Gracile capuchins (Cebus; H2) positive selection results 15 Section 5: Extended results: Ancestral Cebinae (H3) positive selection results 16 Section 6: Extended results: Across-capuchins (H3a) positive selection results 17 Section 7: Extended results: Ancestral Cebidae (H4) positive selection results 18 Section 8: Extended results: Squirrel monkeys (Saimiri; H5) positive selection results 19 Figs. S1 to S3 20 Tables S1–S3, S5–S7, S10, and S23 21 References (94 to 172) 22 23 Other Supplementary Materials for this manuscript include the following: 24 Tables S4, S8, S9, S11–S22, and S24–S44 1 25 1) Extended methods & results: Robust capuchin reference genome 26 1.1 Genome assembly: versions and accessions 27 The version of the genome assembly used in this study, Sape_Mango_1.0, was uploaded to a 28 Zenodo repository (see data availability). An assembly (Sape_Mango_1.1) with minor 29 modifications including the removal of two short scaffolds and the addition of the mitochondrial 30 genome assembly was uploaded to NCBI under the accession JAGHVQ. The BioProject and 31 BioSample NCBI accessions for this project and sample (Mango) are PRJNA717806 and 32 SAMN18511585. -

An Integrated and Validated Compendium of Ciliary Genes

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/123455; this version posted April 3, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-ND 4.0 International license. 1 CiliaCarta: an integrated and validated compendium 2 of ciliary genes 3 Authors 4 Teunis J. P. van Dam1*#, Julie Kennedy2, Robin van der Lee1, Erik de Vrieze3,4, Kirsten A. Wunderlich5, 5 Suzanne Rix6, Gerard W. Dougherty7, Nils J. Lambacher2, Chunmei Li8, Victor L. Jensen8, Michel R. 6 Leroux8, Rim Hjeij7, Nicola Horn9, Yves Texier9§, Yasmin Wissinger9, Jeroen van Reeuwijk10, 7 Gabrielle Wheway11†, Barbara Knapp5, Jan F. Scheel5¶, Brunella Franco12,13, Dorus A. Mans10, Erwin 8 van Wijk3,4, François Képès14, Gisela G. Slaats15, Grischa Toedt16, Hannie Kremer3,4,17, Heymut 9 Omran7, Katarzyna Szymanska11, Konstantinos Koutroumpas14, Marius Ueffing9, Thanh-Minh T. 10 Nguyen10, Stef J.F. Letteboer10, Machteld M. Oud10, Sylvia E. C. van Beersum10, Miriam Schmidts10,18, 11 Philip L. Beales6, Qianhao Lu19,20, Rachel H. Giles15, Radek Szklarczyk1‡, Robert B. Russell19,20, Toby J. 12 Gibson16, Colin A. Johnson11, Oliver E. Blacque2, Uwe Wolfrum5, Karsten Boldt9, Ronald Roepman10, 13 Victor Hernandez-Hernandez6, Martijn A. Huynen1* 14 Affiliations 15 1Centre for Molecular and Biomolecular informatics, Radboud University Medical Center, PO Box 16 9101, 6500 HB Nijmegen, the Netherlands 17 2School of Biomolecular and Biomedical