Press Richard Deacon Interview Art Interview Online, May 19, 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

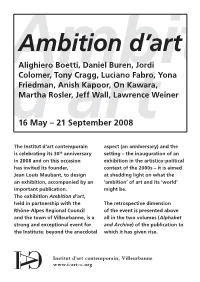

D'art Ambition D'art Alighiero Boetti, Daniel Buren, Jordi Colomer, Tony

Ambition d’art AmbitionAlighiero Boetti, Daniel Buren, Jordi Colomer, Tony Cragg, Luciano Fabro, Yona Friedman, Anish Kapoor, On Kawara, Martha Rosler, Jeff Wall, Lawrence Weiner d’art16 May – 21 September 2008 The Institut d’art contemporain aspect (an anniversary) and the is celebrating its 30th anniversary setting – the inauguration of an in 2008 and on this occasion exhibition in the artistico-political has invited its founder, context of the 2000s – it is aimed Jean Louis Maubant, to design at shedding light on what the an exhibition, accompanied by an ‘ambition’ of art and its ‘world’ important publication. might be. The exhibition Ambition d’art, held in partnership with the The retrospective dimension Rhône-Alpes Regional Council of the event is presented above and the town of Villeurbanne, is a all in the two volumes (Alphabet strong and exceptional event for and Archive) of the publication to the Institute: beyond the anecdotal which it has given rise. Institut d’art contemporain, Villeurbanne www.i-art-c.org Any feedback in the exhibition is Yona Friedman, Jordi Colomer) or less to commemorate past history because they have hardly ever been than to give present and future shown (Martha Rosler, Alighiero history more density. In fact, many Boetti, Jeff Wall). Other works have of the works shown here have already been shown at the Institut never been seen before. and now gain fresh visibility as a result of their positioning in space and their artistic company (Luciano Fabro, Daniel Buren, Martha Rosler, Ambition d’art Tony Cragg, On Kawara). For the exhibition Ambition d’art, At the two ends of the generation Jean Louis Maubant has chosen chain, invitations have been eleven artists for the eleven rooms extended to both Jordi Colomer of the Institut d’art contemporain. -

TURNER PRIZE: Most Prestigious— Yet Also Controversial

TURNER PRIZE: Most prestigious— yet also controversial Since its inception, the Turner Prize has been synonymous with new British art – and with lively debate. For while the prize has helped to build the careers of a great many young British artists, it has also generated controversy. Yet it has survived endless media attacks, changes of terms and sponsor, and even a year of suspension, to arrive at its current status as one of the most significant contemporary art awards in the world. How has this controversial event shaped the development of British art? What has been its role in transforming the new art being made in Britain into an essential part of the country’s cultural landscape? The Beginning The Turner Prize was set up in 1984 by the Patrons of New Art (PNA), a group of Tate Gallery benefactors committed to raising the profile of contemporary art. 1 The prize was to be awarded each year to “the person who, in the opinion of the jury, has made the greatest contribution to art in Britain in the previous twelve months”. Shortlisted artists would present a selection of their works in an exhibition at the Tate Gallery. The brainchild of Tate Gallery director Alan Bowness, the prize was conceived with the explicit aim of stimulating public interest in contemporary art, and promoting contemporary British artists through broadening the audience base. At that time, few people were interested in contemporary art. It rarely featured in non-specialist publications, let alone in the everyday conversations of ordinary members of the public. The Turner Prize was named after the famous British painter J. -

Anya Gallaccio

ANYA GALLACCIO Born Paisley, Scotland 1963 Lives London, United Kingdom EDUCATION 1985 Kingston Polytechnic, London, United Kingdom 1988 Goldsmiths' College, University of London, London, United Kingdom SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 NOW, The Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, Scotland Stroke, Blum and Poe, Los Angeles, CA 2018 dreamed about the flowers that hide from the light, Lindisfarne Castle, Northumberland, United Kingdom All the rest is silence, John Hansard Gallery, Southampton, United Kingdom 2017 Beautiful Minds, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, United Kingdom 2015 Silas Marder Gallery, Bridgehampton, NY Lehmann Maupin, New York, NY Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, San Diego, CA 2014 Aldeburgh Music, Snape Maltings, Saxmundham, Suffolk, United Kingdom Blum and Poe, Los Angeles, CA 2013 ArtPace, San Antonio, TX 2011 Thomas Dane Gallery, London, United Kingdom Annet Gelink, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 2010 Unknown Exhibition, The Eastshire Museums in Scotland, Kilmarnock, United Kingdom Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 2009 So Blue Coat, Liverpool, United Kingdom 2008 Camden Art Centre, London, United Kingdom 2007 Three Sheets to the wind, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, United Kingdom 2006 Galeria Leme, São Paulo, Brazil One art, Sculpture Center, New York, NY 2005 The Look of Things, Palazzo delle Papesse, Siena, Italy Blum and Poe, Los Angeles, CA Silver Seed, Mount Stuart Trust, Isle of Bute, Scotland 2004 Love is Only a Feeling, Lehmann Maupin, New York, NY 2003 Love is only a feeling, Turner Prize Exhibition, -

Contemporary Art Society Annual Report 1993

THE CONTEMPORARY ART SOCIETY The Annual General Meeting of the Contemporary Art Society will be held on Wednesday 7 September, 1994 at ITN, 200 Gray's Inn Road, London wcix 8xz, at 6.30pm. Agenda 1. To receive and adopt the report of the committee and the accounts for the year ended 31 December 1993, together with the auditors' report. 2. To reappoint Neville Russell as auditors of the Society in accordance with section 384 (1) of the Companies Act 1985 and to authorise the committee to determine their remunera tion for the coming year. 3. To elect to the committee Robert Hopper and Jim Moyes who have been duly nominated. The retiring members are Penelope Govett and Christina Smith. In addition Marina Vaizey and Julian Treuherz have tendered their resignation. 4. Any other business. By order of the committee GEORGE YATES-MERCER Company Secretary 15 August 1994 Company Limited by Guarantee, Registered in London N0.255486, Charities Registration No.2081 y8 The Contemporary Art Society Annual Report & Accounts 1993 PATRON I • REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother PRESIDENT Nancy Balfour OBE The Committee present their report and the financial of activities and the year end financial position were VICE PRESIDENTS statements for the year ended 31 December 1993. satisfactory and the Committee expect that the present The Lord Croft level of activity will be sustained for the foreseeable future. Edward Dawe STATEMENT OF COMMITTEE'S RESPONSIBILITIES Caryl Hubbard CBE Company law requires the committee to prepare financial RESULTS The Lord McAlpine of West Green statements for each financial year which give a true and The results of the Society for the year ended The Lord Sainsbury of Preston Candover KG fair view of the state of affairs of the company and of the 31 December 1993 are set out in the financial statements on Pauline Vogelpoel MBE profit or loss of the company for that period. -

Turner Prize Winner Lubaina Himid to Exhibit Unique Instructional Version of Vernet’S Studio in South Africa

NOT A SINGLE STORY –Turner Prize winner Lubaina Himid to exhibit unique instructional version of Vernet’s Studio in South Africa. Hosted from 12 May – 29 July at the NIROX Sculpture Park in the Cradle of Humankind, NOT A SINGLE STORY is a collaboration between the NIROX Foundation, South Africa and Wanås Konst, The Wanås Foundation, Sweden. NOT A SINGLE STORY is the NIROX Winter sculpture exhibition 2018. The exhibition and its educational program are made possible with the support of The Swedish Postcode Foundation, The Swedish Institute and the Swedish Embassy. NIROX Foundation: Facebook | Twitter| Instagram Wanås Konst, The Wanås Foundation: Facebook | Instagram On Saturday 12 May, the NIROX Sculpture Park opens the exhibition NOT A SINGLE STORY. The title references “The Danger of a Single Story,” a TED Talk presented by acclaimed novelist and feminist writer, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, which posits that our differences strengthen rather than divides us. Curated by Elisabeth Millqvist and Mattias Givell, co-directors of the Wanås Foundation, the exhibition is a celebration of diversity and includes works made of wishes, space blankets and large scale sound pieces by established and emerging artists from the continent and abroad. Notable is the participation of 2017 Turner Prize winner Lubaina Himid (ZNZ/UK) who will exhibit eight figures from the 26-piece installation Vernet’s Studio uniquely produced under instruction by studio artists at NIROX. This installation comprises of female artists from art history featuring the likes of Frida Kahlo, Rosemary Trocke, Maud Sulter and Georgia O’Keefe. This work is exemplary of Himid’s practise, which is embedded in foregrounding stories and narratives. -

Grayson Perry

GRAYSON PERRY Born in Chelmsford in 1960 Lives and works in London SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2017 The Most Popular Art Exhibition Ever!, Serpentine Galleries, London; travelling to Arnolfini, Bristol (2017) 2016 Hold Your Beliefs Lightly, Bonnefantenmuseum, Maastricht, The Netherlands; travelling to ARoS Aarhus Art Museum, Aarhus, Denmark My Pretty Little Art Career, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney 2015 Provincial Punk, Turner Contemporary, Margate Small Differences, Pera Museum, Istanbul, Turkey 2014 Who are You?, National Portrait Gallery, London Walthamstow Tapestry, Winchester Discovery Centre 2013 - 2017 The Vanity of Small Differences (UK Art Fund/British Council National and International Tour): Sunderland Museum & Winter Gardens, Tyne and Wear; Manchester Art Gallery, Manchester; Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, Birmingham; Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool; Leeds City Art Gallery, Leeds; Victoria Art Gallery, Bath; The Herbert Museum and Art Gallery, Coventry; Croome Park, Worcester; Beaney House of Art and Knowledge, Canterbury; Izolyatsia Platform for Cultural Initiatives, Kyiv, Ukraine; Museum of Contemporary Art Vojvodina, Novi Sad, Serbia; National Gallery, Pristina, Kosovo; Art Gallery of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Sarajevo, Bosnia 2012 The Vanity of Small Differences, Victoria Miro Gallery, London The Walthamstow Tapestry, William Morris Gallery, Walthamstow 2011 Grayson Perry: The Tomb of the Unknown Craftsman, The British Museum, London Grayson Perry, Louis Vuitton Maison, London Grayson Perry: Visual Dialogues, Manchester Art -

Anya Gallaccio

Anya Gallaccio 1963 Born in Paisley, Scotland Lives and works in London, UK Education 1985-1988 Goldsmiths’ College, University of London, UK 1984-1985 Kingston Polytechnic, London, UK Residencies and awards 2004 Headlands Center for the Arts, Sansalitos, California, US 2003 Nominee for the Turner Prize, Tate Britain, London, UK 2002 1871 Fellowship, Rothermere American Institute, Oxford, UK San Francisco Art Institute, California, US 1999 Paul Hamlyn Award for Visual Artists, Paul Hamlyn Foundation Award, London, UK 1999 Kanazawa College of Art, JP 1998 Sargeant Fellowship, The British School at Rome, IT 1997 Jan-March Art Pace, International Artist-In-Residence Programme, Foundation for Contemporary Art, San Antonio Texas, US Solo Exhibitions 2015 Lehmann Maupin, New York, US 2014 Stroke, Jupiter Artland, Edinburgh, UK SNAP, Art at the Aldeburgh Festival, Suffolk, UK Blum&Poe, Los Angeles, US 2013 This much is true, Artpace, San Antonio, Texas, US Creation/destruction, The Holden Gallery, Manchester, UK 2012 Red on Green, Jupiter Artland, Edinburgh, UK 2011 Highway, Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam, NL Where is Where it’s at, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK 2010 Unknown Exhibition, The Eastshire Museums in Scotland including the Dick Institiute, the Baird Institute and the Doon Valley Museum, Kilmarnock, UK 2009 Inaugural Exhibition, Blum & Poe Gallery, Los Angeles, CA, US Lehmann Maupin Gallery, New York, US 2008 Comfort and Conversation, Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam, NL That Open Space Within, Camden Arts Center, London, UK Kinsale -

Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics Author(S): Claire Bishop Source: October, Vol

Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics Author(s): Claire Bishop Source: October, Vol. 110 (Autumn, 2004), pp. 51-79 Published by: The MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3397557 Accessed: 19/10/2010 19:54 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=mitpress. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to October. http://www.jstor.org Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics CLAIRE BISHOP The Palais de Tokyo On the occasion of its opening in 2002, the Palais de Tokyo immediately struck the visitor as different from other contemporary art venues that had recently opened in Europe. -

Shirazeh Houshiary B

Shirazeh Houshiary b. 1955, Shiraz, Iran 1976-79 Chelsea School of Art, London 1979-80 Junior Fellow, Cardiff College of Art 1997 Awarded the title Professor at the London Institute Solo Exhibitions 1980 Chapter Arts Centre, Cardiff 1982 Kettle's Yard Gallery, Cambridge 1983 Centro d'Arte Contemporanea, Siracusa, Italy Galleria Massimo Minini, Milan Galerie Grita Insam, Vienna 1984 Lisson Gallery, London (exh. cat.) 1986 Galerie Paul Andriesse, Amsterdam 1987 Breath, Lisson Gallery, London 1988-89 Centre d'Art Contemporain, Musée Rath, Geneva (exh. cat.), (toured to The Museum of Modern Art, Oxford) 1992 Galleria Valentina Moncada, Rome Isthmus, Lisson Gallery, London 1993 Dancing around my ghost, Camden Arts Centre, London (exh. cat.) 1993-94 Turning Around the Centre, University of Massachusetts at Amherst Fine Art Center (exh. cat.), (toured to York University Art Gallery, Ontario and to University of Florida, the Harn Museum, Gainsville) 1994 The Sense of Unity, Lisson Gallery, London 1995-96 Isthmus, Le Magasin, Centre National d'Art Contemporain, Grenoble (exh. cat.), (touring to Museum Villa Stuck, Munich, Bonnefanten Museum, Maastricht, Hochschule für angewandte Kunst, Vienna). Organised by the British Council 1997 British Museum, Islamic Gallery 1999 Lehmann Maupin Gallery, New York, NY 2000 Self-Portraits, Lisson Gallery, London 2002 Musuem SITE, Santa Fe, NM 2003 Shirazeh Houshiary - Recent Works, Lehman Maupin, New York Shirazeh Houshiary Tate Liverpool (from the collection) Lisson Gallery, London 2004 Shirazeh Houshiary, -

Listed Exhibitions (PDF)

G A G O S I A N G A L L E R Y Anish Kapoor Biography Born in 1954, Mumbai, India. Lives and works in London, England. Education: 1973–1977 Hornsey College of Art, London, England. 1977–1978 Chelsea School of Art, London, England. Solo Exhibitions: 2016 Anish Kapoor. Gagosian Gallery, Hong Kong, China. Anish Kapoor: Today You Will Be In Paradise. Gladstone Gallery, New York, NY. Anish Kapoor. Lisson Gallery, London, England. Anish Kapoor. Lisson Gallery, Milan, Italy. Anish Kapoor. Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo, Mexico City, Mexico. 2015 Descension. Galleria Continua, San Gimignano, Italy. Anish Kapoor. Regen Projects, Los Angeles, CA. Kapoor Versailles. Gardens at the Palace of Versailles, Versailles, France. Anish Kapoor. Gladstone Gallery, Brussels, Belgium. Anish Kapoor. Lisson Gallery, London, England. Anish Kapoor: Prints from the Collection of Jordan D. Schnitzer. Portland Art Museum, Portland, OR. Anish Kapoor chez Le Corbusier. Couvent de La Tourette, Eveux, France. Anish Kapoor: My Red Homeland. Jewish Museum and Tolerance Centre, Moscow, Russia. 2013 Anish Kapoor in Instanbul. Sakıp Sabancı Museum, Istanbul, Turkey. Anish Kapoor Retrospective. Martin Gropius Bau, Berlin, Germany 2012 Anish Kapoor. Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, Australia. Anish Kapoor. Gladstone Gallery, New York, NY. Anish Kapoor. Leeum – Samsung Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea. Anish Kapoor, Solo Exhibition. PinchukArtCentre, Kiev, Ukraine. Anish Kapoor. Lisson Gallery, London, England. Flashback: Anish Kapoor. Longside Gallery, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, West Bretton, England. Anish Kapoor. De Pont Foundation for Contemporary Art, Tilburg, Netherlands. 2011 Anish Kapoor: Turning the Wold Upside Down. Kensington Gardens, London, England. Anish Kapoor: Flashback. Nottingham Castle Museum, Nottingham, England. -

Press Release

For Immediate Release. Tony Cragg February 1 – March 10, 2012 Opening reception: Wednesday, February 1st, 6-8 pm. Marian Goodman Gallery is delighted to present an exhibition of new sculpture by Tony Cragg opening on Wednesday, February 1st, and continuing through Saturday, March 10th. The exhibition will feature recent sculptures in bronze, corten steel, wood, cast iron, and stone. Concurrently, and accompanying the gallery presentation, a group of large scale works will be exhibited at The Sculpture Garden at 590 Madison Avenue (entrance at 56th Street). The Sculpture Garden is open to the public daily from 8 am to 10 pm. Tony Cragg is one of the most distinguished contemporary sculptors working today. During the past year, there have been several important solo exhibitions of his work worldwide: Seeing Things at The Nasher Sculpture Center, Dallas; Figure In/ Figure Out at The Louvre, Paris; Museum Küppersmühle für Moderne Kunst, Duisburg, Germany; Tony Cragg in 4 D from Flux to Stability at The International Gallery of Modern Art, Venice; It is, Isn’t It at the Church of San Cristoforo, Lucca, Italy; and Tony Cragg: Sculptures and Drawings at The Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh. Cragg’s work developed within the context of diverse influences including early experiences in a scientific laboratory; English landscape and time-based art, a precursor to the presenting of found objects and fragments that characterized early performative work; and Minimalist sculpture, an antecedent to the stack, additive and accumulation works of the mid- seventies. Cragg has widened the boundaries of sculpture with a dynamic and investigative approach to materials, to images, and objects in the physical world, and an early use of found industrial objects and fragments. -

This Book Is a Compendium of New Wave Posters. It Is Organized Around the Designers (At Last!)

“This book is a compendium of new wave posters. It is organized around the designers (at last!). It emphasizes the key contribution of Eastern Europe as well as Western Europe, and beyond. And it is a very timely volume, assembled with R|A|P’s usual flair, style and understanding.” –CHRISTOPHER FRAYLING, FROM THE INTRODUCTION 2 artbook.com French New Wave A Revolution in Design Edited by Tony Nourmand. Introduction by Christopher Frayling. The French New Wave of the 1950s and 1960s is one of the most important movements in the history of film. Its fresh energy and vision changed the cinematic landscape, and its style has had a seminal impact on pop culture. The poster artists tasked with selling these Nouvelle Vague films to the masses—in France and internationally—helped to create this style, and in so doing found themselves at the forefront of a revolution in art, graphic design and photography. French New Wave: A Revolution in Design celebrates explosive and groundbreaking poster art that accompanied French New Wave films like The 400 Blows (1959), Jules and Jim (1962) and The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964). Featuring posters from over 20 countries, the imagery is accompanied by biographies on more than 100 artists, photographers and designers involved—the first time many of those responsible for promoting and portraying this movement have been properly recognized. This publication spotlights the poster designers who worked alongside directors, cinematographers and actors to define the look of the French New Wave. Artists presented in this volume include Jean-Michel Folon, Boris Grinsson, Waldemar Świerzy, Christian Broutin, Tomasz Rumiński, Hans Hillman, Georges Allard, René Ferracci, Bruno Rehak, Zdeněk Ziegler, Miroslav Vystrcil, Peter Strausfeld, Maciej Hibner, Andrzej Krajewski, Maciej Zbikowski, Josef Vylet’al, Sandro Simeoni, Averardo Ciriello, Marcello Colizzi and many more.