Joost Jansen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Len European Water Polo Championships

2020 LEN EUROPEAN WATER POLO CHAMPIONSHIPS PAST AND PRESENT RESULTS Cover photo: The Piscines Bernat Picornell, Barcelona was the home of the European Water Polo Championships 2018. Situated high up on Montjuic, it made a picturesque scene by night. This photo was taken at the Opening Ceremony (Photo: Giorgio Scala/Deepbluemedia/Insidefoto) Unless otherwise stated, all photos in this book were taken at the 2018 European Championships in Barcelona 2 BUDAPEST 2020 EUROPEAN WATER POLO CHAMPIONSHIPS PAST AND PRESENT RESULTS The silver, gold and bronze medals (left to right) presented at the 2018 European Championships (Photo: Giorgio Scala/Deepbluemedia/Insidefoto) CONTENTS: European Water Polo Results – Men 1926 – 2018 4 European Water Polo Championships Men’s Leading Scorers 2018 59 European Water Polo Championships Men’s Top Scorers 60 European Water Polo Championships Men’s Medal Table 61 European Water Polo Championships Men’s Referees 63 European Water Polo Club Competitions – Men 69 European Water Polo Results – Women 1985 -2018 72 European Water Polo Championships Women’s Leading Scorers 2018 95 European Water Polo Championships Women’s Top Scorers 96 European Water Polo Championships Women’s Medal Table 97 Most Gold Medals won at European Championships by Individuals 98 European Water Polo Championships Women’s Referees 100 European Water Polo Club Competitions – Women 104 Country By Country- Finishing 106 LEN Europa Cup 109 World Water Polo Championships 112 Olympic Water Polo Results 118 2 3 EUROPEAN WATER POLO RESULTS MEN 1926-2020 -

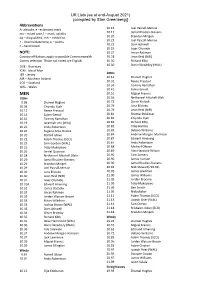

UK Lists (As at End-August 2021) (Compiled by Stan Greenberg)

UK Lists (as at end - August 2021) (compiled by Stan Greenberg)] Abbreviations A - altitude, e – estimated mark 10.16 Joel Pascall - Menzie mx – mixed race,? – mark, validity 10.17 Jamal Rhoden - Stevens dq – disqualified, exh – exhibition 10.20 Brandon Mingeli + - intermediate time, p – points 10.22 Joel Pascall - Menzie h – hand timed 10 .22 Dom Ashwell 10.25 Isaac Olumide NOTE: 10.27 Imran Rahman C ountry affiliations apply to possible Commo nwealth 10.28 Leon Reid (NIR) Games selection . Those n ot noted are English 10.30 Richard Kilty GUE - Guernsey 10.30 Daniel Beadsley (WAL) IOM - Isle of Man JER - .Jersey 200m NIR – Northern Ireland 20.14 Zharnel Hughes SCO – Scotland 20.31 Reece Prescod WAL - Wales 20.34 Tommy Ramdhan 20.41 Adam Gemili MEN 20.51 Miguel Francis 100m 20.56 Nethane el Mitchell - Blak 9.98 Zharnel Hughes 20.72 Derek Kinlock 10.03 Chijindu Ujah 20.79 Jona Efoloko 10.12 Reece Prescod 20.79 Leon Reid (NIR) 10.14 Adam Gemili 20.81 Shemar Boldizsar 10.16 Tommy Ramdhan 20.82 Chijindu Ujah 10.19 Jeremiah Azu (WAL) 20.82 Richard Kilty 10.20 Andy Robertson 20.82 Toby Harries 10.20 Eugene Amo - Dadzie 20.83 Delano Williams 10.20 Romell Glave 20.84 Andrew Morgan - Morrison 10.22 Adam Thomas (SCO) 20.87 Edward Amaning 10.25 Sam Gordon (WAL) 20.87 Andy Robertson 10.25 Toby Makoyawo 20.88 Michael Ohioze 10.26 Jerriel Quainoo 20.89 Alex Haydock - Wilson 10.28 Nethaneel Mitchell - Blake 20.90 Tom Somers 10.29 Jamal Rhoden - Stevens 20.90 James Hanson 10.29 Brandon Mingeli 20.90 Jamal Rhoden - Stevens 10.29 Joel Pascall - Menzie -

MEET-Program-Nacac-New-Life-Inv-June-4-2342-Pm-Rev3

FinishTiming - Contractor License Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 11:42 PM 6/4/2021 Page 1 NACAC NEW LIFE INVITATIONAL - 6/5/2021 WORLD ATHLETICS CONTINENTAL TOUR SILVER Ansin Sports Complex Meet Program - NACAC New Life Invitational Event 101 Men Discus Throw Saturday 6/5/2021 - 2:00 PM OLY: 66.00m WORLD: 74.08m 6/6/1986 Jurgen Schult, GDR NACAC: 71.32m 6/4/1983 Ben Pluncknett, USA Pos Comp# Name Age Team Seed Mark Finals Place Flight 1 of 1 Finals 1 92 Chad Wright Jamaica 66.54m______________________ _______ 2 114 Alex Rose Samoa 67.46m______________________ _______ 3 89 Traves Smikle Jamaica 67.57m______________________ _______ 4 72 Kai Chang Jamaica 62.00m______________________ _______ 5 190 Josh Syrotchen United States 63.20m______________________ _______ 6 52 Colin Quirke Ireland 62.18m______________________ _______ 7 74 Fedrick Dacres Jamaica 70.78m______________________ _______ FinishTiming - Contractor License Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 11:42 PM 6/4/2021 Page 2 NACAC NEW LIFE INVITATIONAL - 6/5/2021 WORLD ATHLETICS CONTINENTAL TOUR SILVER Ansin Sports Complex Meet Program - NACAC New Life Invitational Event 102 Women Long Jump Saturday 6/5/2021 - 2:00 PM OLY: 6.82m WORLD: 7.52m 6/11/1988 Galina Chistyakova, URS NACAC: 7.49m 7/31/1994 Jackie Joyner-Kersee, USA Pos Comp# Name Age Team Seed Mark Finals Place Flight 1 of 1 Finals 1 156 Malaina Payton United States 6.81m______________________ _______ 2 33 Mariah Toussaint Dominica 6.09m______________________ _______ 3 53 Sabina Allen Jamaica 6.67m______________________ _______ 4 21 Christabel Nettey -

Fina Water Polo Scoresheet

FINA MATCH DETAILS WATER POLO SCORESHEET GAME OFFICIALS GAME ITALY vs NETHERLANDS Time Player Colour Comment Score Time Player Colour Comment Score REFEREES Radoslaw KORYZNA (POL) - Adrian ALEXANDRESCU (ROU) 8.00 4 W # 4.13 3 W E GAME NO. 20th 6.43 8 W G 1-0 1.56 10 W E SECRETARIES Giovanna BLASI - Giorgia FILIPPINI 4.39 5 B E 1.56 B TO VENUE Trieste (ITA) - Polo Natatorio "B. Bianchi" 4.32 4 W EG 2-0 0.15 5 W E TIMEKEEPERS Tiziana INNOCENTI - Gernot HAENTSCHEL (GER) 4.02 4 W G 3-0 - - - - - DATE 06/04/2016 TIME 20.30 3.15 4 B E GOAL JUDGES Dion WILLIS (RSA) - Pascal BOUCHEZ (FRA) 3.15 W TO 1.41 9 B G 3-1 White Caps 0.34 B TO Blue Caps TEAM ITALY - - - - - TEAM NETHERLANDS 8.00 4 W # 6.49 4 W G 4-1 Coach: Alessandro CAMPAGNA Coach: Robin VAN GALEN 6.25 3 W E Assistant Assistant Amedeo POMILIO 6.20 3 B EG 4-2 Hans NIEUWENBURG Coach: 5.56 6 W E Coach: 5.49 6 W P Official: Alessandro AMATO Official: Ross WATSON 5.49 Coach W YC Goals by Quarter 5.49 6 B PG 4-3 Goals by Quarter No. Player Major Fouls No. Player Major Fouls 1 2 3 4 PSO 5.37 4 B E 1 2 3 4 PSO 5.23 12 W EG 5-3 Eelco Titus 01 Stefano TEMPESTI © 01 3.03 2 W E WAGENAAR 3.03 B TO Yoran 02 Francesco DI FULVIO E 02 E E 2.48 6 B EG 5-4 FRAUENFELDER 2.21 11 W G 6-4 03 Niccolò GITTO E E 03 Jorn WINKELHORST E 1 1.27 5 W G 7-4 0.54 W TO Ruud Hendricus Petrus 04 Pietro FIGLIOLI E 2 2 04 E E E 0.40 4 W G 8-4 VAN DER HORST 0.20 7 W E Lucas Cornelis 05 Alex GIORGETTI E 1 1 1 05 E - - - - - Johannes GIELEN Michael Alexandre 8.00 9 W # 06 E E 06 Robin LINDHOUT 2 1 BODEGAS 7.32 2 B E 6.21 9 W -

Il Vostro Giornale - 1 / 2 - 01.10.2021 2

1 Pallanuoto, il capitano Stefano Tempesti: “I giovani portieri devono fare esperienza internazionale” di Redazione 30 Ottobre 2012 – 21:06 Savona. Sono diciotto i giocatori convocati da Alessandro Campagna per la sfida di World League contro la Russia. La parte del leone la fa ancora la Pro Recco, con un otto atleti: Matteo Aicardi, Niccolò Figari, Maurizio Felugo, Pietro Figlioli, Deni Fiorentini, Stefano Luongo, Niccolò Gitto e Stefano Tempesti. Ci sono poi il savonese Luca Damonte e Tommaso Vergano della Rari Nantes Bogliasco. Pertanto, più di metà truppa azzurra milita in squadre liguri. E’ il capitano della nazionale e della Pro Recco, Stefano Tempesti, ad analizzare il punto di partenza di questa nuova avventura. “Si torna in acqua dopo Londra con una squadra con qualche novità – afferma -. Non ci sono più Perez, Giacoppo e Pastorino, però sono cambi che il mister deve fare per provare nuovi giocatori in vista di questo quadriennio che si apre ora. Sarà un percorso lungo, però allo stesso tempo ritrovarsi all’arrivo è un attimo, quindi dobbiamo iniziare già da adesso a provare i nuovi innesti e vedere cosa sarà di questa nuova avventura. L’obiettivo sono le Olimpiadi, ma sicuramente nei tre anni che ci separano da Rio non ci saranno solo tappe di passaggio ma banchi di prova importanti”. Stefano Tempesti, classe 1979, è in nazionale dal 1999. Lo staff azzurro deve lavorare anche al suo erede. “Ci sono dei portieri validi in Italia – dichiara il capitano -. Il portiere, però, deve dimostrare di essere valido sul campo. La differenza tra il campo italiano e quello internazionale è tanta, c’è un abisso. -

2014 Collegiate U20 Bests As of 6/17/2014 12:23:27 PM Men's 60 Meters ALL-TIME BESTS World U20 Mark LEWIS-FRANCIS 82J Great Britain & N.I

A look ahead to Oregon14 -- IAAF World Junior Championships 2014 Collegiate U20 Bests as of 6/17/2014 12:23:27 PM Men's 60 Meters ALL-TIME BESTS World U20 Mark LEWIS-FRANCIS 82J Great Britain & N.I. GBR 6.51 <i> 3/11/2001 Lisbon, Portugal U.S. U20 D'Angelo CHERRY 90J Mississippi State USA 6.52 <i> 3/1/2009 Boston, Mass. USATF Indoor Championships SEASON LEADERS World U20 Yoshihide KIRYU 95J Japan JPN 6.62q <i> 3/9/2014 Sopot, Poland IAAF World Indoor Championships Jalen MILLER FR 95J Mississippi USA 6.62 <i> 2/8/2014 New York, N.Y. Armory Collegiate Invitational U.S. U20 Jalen MILLER FR 95J Mississippi USA 6.62 <i> 2/8/2014 New York, N.Y. Armory Collegiate Invitational 2014 SEASON BESTS (ALL-CONDITIONS) BY U20 COLLEGIANS Rank Athlete Hometown/Country Collegiate Institution Mark Date Meet 1 (1) Jalen MILLER FR 95J Tunica, Miss. USA Mississippi 6.62 <i> 2/8 Armory Collegiate Invitational 2 – Miller USA Mississippi 6.63q <i> 3/1 SEC Indoor Championships 3 – Miller USA Mississippi 6.64qA <i> 3/14 NCAA Division I Indoor Champio 4 – Bromell USA Baylor 6.65qA <i> 3/14 NCAA Division I Indoor Champio (2) Trayvon BROMELL FR 95J St. Petersburg, Fla. USA Baylor 6.65 <i> 2/8 Aggie Invitational – Bromell USA Baylor 6.65 <i> 1/25 Rod McCravy Memorial 7 – Bromell USA Baylor 6.66 <i> 1/18 Texas A&M 10-Team Invitationa 8 – Bromell USA Baylor 6.67q <i> 2/28 Big 12 Indoor Championships – Miller USA Mississippi 6.67qA <i> 2/14 Don Kirby Invitational – Bromell USA Baylor 6.67q <i> 2/7 Aggie Invitational – Miller USA Mississippi 6.67 <i> 1/18 Auburn Indoor Invitational -- (3) Tremayne ACY FR 95J Dallas, Texas USA LSU 6.75 <i> 2/15 Tyson Invitational -- (4) Marcus HARRIS FR 95J Aurora, Colo. -

School Sport Australia Water Polo Championship History

School Sport Australia Water Polo Championship History Past Winners Year Venue Boys Girls Boys Girls RK Mullins ASSWPA Perpetual Perpetual MC Turnbull Janet Raynor Trophy Trophy Trophy Trophy 1978 Sydney NSW 1979 Canberra NSW 1980 Adelaide NSW 1981 Perth QLD NSW 1982 Melbourne WA NSW 1983 Brisbane NSW NSW 1984 Hobart VIC NSW 1985 Sydney NSW NSW 1986 Canberra NSW NSW 1987 Adelaide NSW NSW 1988 Sydney NSW NSW 1989 Melbourne NSW NSW 1990 Brisbane NSW NSW VIC QLD 1991 Sydney NSW NSW WA ACT 1992 Perth NSW NSW WA WA 1993 Canberra NSW NSW QLD ACT 1994 Perth NSW NSW WA QLD 1995 Melbourne NSW NSW ACT WA 1996 Brisbane NSW NSW VIC QLD 1997 Sydney NSW NSW QLD ACT 1998 Hobart NSW NSW WA WA 1999 Perth QLD QLD QLD WA 2000 Canberra NSW NSW NSW ACT 2001 Melbourne NSW NSW QLD WA 2002 Brisbane ACT NSW ACT ACT 2003 Picton NSW NSW WA TAS 2004 Canberra ACT NSW QLD ACT 2005 Sunshine Coast ACT NSW NSW QLD 2006 Sydney NSW NSW Not awarded Not awarded 2007 Melbourne NSW NSW VIC QLD 2008 Brisbane NSW NSW QLD QLD Year ASSWPA - Most Outstanding Player BOYS GIRLS 1984 Nathan O'Brien - QLD 1985 Simon Gould - NSW 1986 Geoff Clark - NSW 1987 Daniel Marsden - ACT 1988 Daniel Marsden - ACt 1989 Craig Miller -NSW 1990 Nathan Thomas - NSW Simone Hankin - NSW 1991 Soul Taylor - NSW Naomi Castle - QLD 1992 Renae Burdack - NSW Bronwyn Mayer - NSW 1993 George Bannah - QLD Taryn Woods - NSW 1994 Gavin Woods - NSW Yvette Higgins - NSW 1995 Antony Matkovic - ACT Joanne Fox - VIC 1996 Nick May - VIC Rebecca Rippon - NSW 1997 Jamie Van Asperin - NSW Lauren Mandell - NSW 1998 Christain -

College Women's 400M Hurdles Championship

College Women's 400m Hurdles Championship EVENT 101THURSDAY 10:00 AM FINAL ON TIME PL ID ATHLETE SCHOOL/AFFILIATION MARK SEC 1 2 Samantha Elliott Johnson C. Smith 57.64 2 2 6 Zalika Dixon Indiana Tech 58.34 2 3 3 Evonne Britton Penn State 58.56 2 4 5 Jessica Gelibert Coastal Carolina 58.84 2 5 19 Faith Dismuke Villanova 59.31 4 6 34 Monica Todd Howard 59.33 6 7 18 Evann Thompson Pittsburgh 59.42 4 8 12 Leah Nugent Virginia Tech 59.61 3 9 11 Iris Campbell Western Michigan 59.80 3 10 4 Rushell Clayton UWI Mona 59.99 2 11 7 Kiah Seymour Penn State 1:00.08 2 12 8 Shana-Gaye Tracey LSU 1:00.09 2 13 14 Deyna Roberson San Diego State 1:00.32 3 14 72 Sade Mariah Greenidge Houston 1:00.37 1 15 26 Shelley Black Penn State 1:00.44 5 16 15 Megan Krumpoch Dartmouth 1:00.49 3 17 10 Danielle Aromashodu Florida Atlantic 1:00.68 3 18 33 Tyler Brockington South Carolina 1:00.75 6 19 21 Ryan Woolley Cornell 1:01.14 4 20 29 Jade Wilson Temple 1:01.15 5 21 25 Dannah Hayward St. Joseph's 1:01.25 5 22 32 Alicia Terry Virginia State 1:01.35 5 23 71 Shiara Robinson Kentucky 1:01.39 1 24 23 Heather Gearity Montclair State 1:01.47 4 25 20 Amber Allen South Carolina 1:01.48 4 26 47 Natalie Ryan Pittsburgh 1:01.53 7 27 30 Brittany Covington Mississippi State 1:01.54 5 28 16 Jaivairia Bacote St. -

RESULTS 200 Metres Men - Semi-Final First 2 in Each Heat (Q) and the Next 2 Fastest (Q) Advance to the Final

Barcelona (ESP) World Junior Championships 10-15 July 2012 RESULTS 200 Metres Men - Semi-Final First 2 in each heat (Q) and the next 2 fastest (q) advance to the Final RESULT NAME COUNTRY AGE DATE VENUE World Junior Record 19.93 Usain BOLT JAM 18 11 Apr 2004 Devonshire Championships Record 20.28 Andrew HOWE ITA 19 16 Jul 2004 Grosseto World Junior Leading 20.14 Tyreek HILL USA 18 26 May 2012 Orlando, FL TEMPERATURE HUMIDITY WIND START TIME 18:59 26° C 60 % -2.8 m/s Heat 1 3 12 July 2012 PLACE BIB NAME COUNTRY DATE of BIRTH LANE RESULT REACTION Fn 1 514 Julian FORTE JAM 07 Jan 93 5 20.83 Q 0.146 2 911 Aaron ERNEST USA 08 Nov 93 7 21.06 Q 0.195 3 55 Teray SMITH BAH 28 Sep 94 4 21.06 q 0.163 4 859 Jereem RICHARDS TRI 13 Jan 94 9 21.14 0.159 5 141 Marlon LAIDLAW-ALLEN CAN 16 Jun 93 8 21.27 0.190 6 354 Josh STREET GBR 31 Jul 94 3 21.36 0.149 1 Zharnel HUGHES AIA 13 Jul 95 6 DNS 12 Cejhae GREENE ANT 06 Oct 95 2 DNS TEMPERATURE HUMIDITY WIND START TIME 19:07 26° C 60 % -4.5 m/s Heat 2 3 12 July 2012 PLACE BIB NAME COUNTRY DATE of BIRTH LANE RESULT REACTION Fn 1 720 Karol ZALEWSKI POL 07 Aug 93 6 20.93 Q PB 0.189 2 848 Delano WILLIAMS TKS 23 Dec 93 4 20.94 Q 0.177 3 761 Siphelo NGQABAZA RSA 04 Feb 93 5 21.24 0.179 3 532 Aska CAMBRIDGE JPN 31 May 93 9 21.24 0.157 5 205 Yoandys LESCAY CUB 05 Jan 94 7 21.27 0.174 6 364 Patrick DOMOGALA GER 14 Mar 93 8 21.58 0.163 7 855 Jonathan FARINHA TRI 16 May 96 2 21.72 0.167 8 258 Óscar HUSILLOS ESP 18 Jul 93 3 21.82 0.163 TEMPERATURE HUMIDITY WIND START TIME 19:15 25° C 70 % -0.5 m/s Heat 3 3 12 July 2012 -

JMC 2015 Communique FINAL

Joint Ministerial Council 2015 Communiqué Preamble 1. The political leaders and representatives of the UK and the Overseas Territories met as the Joint Ministerial Council (JMC) at Lancaster House in London on 1 and 2 December. We welcomed the Premier of Bermuda and the newly elected Chief Minister of Anguilla to their first Council and congratulated the Premier of BVI and the Chief Minister of Gibraltar on their recent re-election. 2. The Joint Ministerial Council is the highest political forum under the 2012 White Paper, bringing together UK Ministers, elected Leaders and Representatives of the Overseas Territories for the purpose of providing leadership and shared vision for the Territories. Its mandate is to monitor and drive forward collective priorities for action in the spirit of partnership. 3. Leaders of the Overseas Territories are democratically elected by the people of the Territories and are accountable to them. We welcomed the presence of UK Government Ministers at the Joint Ministerial Council, and the greater engagement of UK government departments in areas where there were identified needs, both giving legitimacy to a relationship of real partnership 4. The UK and the Territories commit to ensure the political, economic, social and educational advancement of the people of the Territories and their just treatment and protection from abuses. The principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples, as enshrined in the UN Charter, applies to the peoples of the Overseas Territories. 5. We affirmed the importance of promoting the right of the peoples of the Territories to self-determination, a collective responsibility of all parts of the UK Government. -

2013 World Championships Statistics – Men's 200M by K Ken Nakamura

2013 World Championships Statistics – Men’s 200m by K Ken Nakamura The records to look for in Moskva: 1) Nobody won 100m/200m double at the Worlds more than once. Can Bolt do it for the second time? 2) Can Bolt win 200m for the third time to surpass Michael Johnson and Calvin Smith? 3) No country other than US ever won multiple medals in this event. Can Jamaica do it? 4) No European won medal at both 100m and 200m? Can Lemaitre change that? All time Performance List at the World Championships Performance Performer Time Wind Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 19.19 -0.3 Usain Bolt JAM 1 Berlin 2009 2 19.40 0.8 Usain Bolt 1 Daegu 2011 3 2 19.70 0.8 Walter Dix USA 2 Daegu 2011 4 3 19.76 -0.8 Tyson Gay USA 1 Osaka 2007 5 4 19.79 0.5 Michael Johnson USA 1 Göteborg 1995 6 5 19.80 0.8 Christophe Lemaitre FRA 3 Daegu 2011 7 6 19.81 -0.3 Alonso Edward PAN 2 Berlin 2009 8 7 19.84 1.7 Francis Obikwelu NGR 1sf2 Sevilla 1999 9 8 19.85 0.3 Frankie Fredericks NAM 1 Stuttgart 1993 9 9 19.85 -0.3 Wallace Spearmon USA 3 Berlin 2009 11 10 19.89 -0.3 Shawn Crawford USA 4 Berlin 2009 12 11 19.90 1.2 Maurice Greene USA 1 Sevilla 1999 13 19.91 -0.8 Usain Bolt 2 Osaka 2007 14 12 19.94 0.3 John Regis GBR 2 Stuttgart 1993 15 13 19.95 0.8 Jaysuma Saidy Ndure NOR 4 Daegu 2011 16 14 19.98 1.7 Marcin Urbas POL 2sf2 Sevilla 1999 16 15 19.98 -0.3 Steve Mullings JAM 5 Berlin 2009 17 16 19.99 0.3 Carl Lewis USA 3 Stuttgart 1993 19 17 20.00 1.2 Claudinei da Silva BRA 2 Sevilla 1999 19 20.00 -0.4 Tyson Gay 1sf2 Osaka 2007 21 20.01 -3.4 Michael Johnson 1 Tokyo 1991 21 20.01 0.3 -

Youth Charter 2019 Youth Manifesto... #Legacyopportunity4all

Youth Charter 2019 Youth Manifesto... #LegacyOpportunity4All Sport, Arts, Culture and Digital Technology... A 26 Year Games Legacy Opportunity for All... YC 2019 Legacy Manifesto CONTENTS 1.0 BACKGROUND: A 26 YEAR GAMES LEGACY... ....................................................................................1 2.0 INTRODUCTION: THE YOUTH AGENDA... ...................................................................................................2 3.0 YOUTH MANIFESTO: CALL TO ACTION... ......................................................................................3 3.1 10 POINT ACTION PLAN EXPLAINED... ..........................................................................................4 3.2 DELIVERY STRUCTURE OF 10 POINT ACTION PLAN... .....................................................................5 3.3 WHY THIS MANIFESTO: SAFEGUARDING OUR YOUNG PEOPLE... .......................................................6 3.4 COST BENEFIT ANALYSIS... .............................................................................................7 3.5 SPORT AS A FUNDAMENTAL HUMAN RIGHT... ..............................................................................8 4.0 YOUTH CHARTER LEGACY CULTURAL FRAMEWORK... .............................................................................9 5.0 POLITICAL PARTY 2019 MANIFESTO PLEDGES FOR YOUTH ...................................................................11 6.0 MANIFESTO REFERENCES ...........................................................................................................16