Adoniram & Ann Judson: Did You Know?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Best Books for Kindergarten Through High School

! ', for kindergarten through high school Revised edition of Books In, Christian Students o Bob Jones University Press ! ®I Greenville, South Carolina 29614 NOTE: The fact that materials produced by other publishers are referred to in this volume does not constitute an endorsement by Bob Jones University Press of the content or theological position of materials produced by such publishers. The position of Bob Jones Univer- sity Press, and the University itself, is well known. Any references and ancillary materials are listed as an aid to the reader and in an attempt to maintain the accepted academic standards of the pub- lishing industry. Best Books Revised edition of Books for Christian Students Compiler: Donna Hess Contributors: June Cates Wade Gladin Connie Collins Carol Goodman Stewart Custer Ronald Horton L. Gene Elliott Janice Joss Lucille Fisher Gloria Repp Edited by Debbie L. Parker Designed by Doug Young Cover designed by Ruth Ann Pearson © 1994 Bob Jones University Press Greenville, South Carolina 29614 Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved ISBN 0-89084-729-0 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 Contents Preface iv Kindergarten-Grade 3 1 Grade 3-Grade 6 89 Grade 6-Grade 8 117 Books for Analysis and Discussion 125 Grade 8-Grade12 129 Books for Analysis and Discussion 136 Biographies and Autobiographies 145 Guidelines for Choosing Books 157 Author and Title Index 167 c Preface "Live always in the best company when you read," said Sydney Smith, a nineteenth-century clergyman. But how does one deter- mine what is "best" when choosing books for young people? Good books, like good companions, should broaden a student's world, encourage him to appreciate what is lovely, and help him discern between truth and falsehood. -

The American Protestant Missionary Network in Ottoman Turkey, 1876-1914

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 4, No. 6(1); April 2014 The American Protestant Missionary Network in Ottoman Turkey, 1876-1914 Devrim Ümit PhD Assistant Professor Founding and Former Chair Department of International Relations Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences Karabuk University Turkey Abstract American missionaries have long been the missing link in the study of the late Ottoman period despite the fact that they left their permanent trade in American as well as Western conceptions of the period such as “Terrible Turk” and “Red Sultan” just to name a few. From the landing of the first two American Protestant missionaries, Levi Parsons and Pliny Fisk, on the Ottoman Empire, as a matter of fact on the Near East, in early 1820, until the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, American missionaries occupied the increasing attention of the Ottoman bureaucracy in domestic and foreign affairs while the mission work in the Ottoman Empire established the largest investment of the American Board of Commissionaries for Foreign Missions (A.B.C.F.M.) in the world, even above China and India, on the eve of the war. The bulk of the correspondence of the Ottoman Ministry of Foreign Affairs for the period was with the United States and this was chiefly concerned about the American mission schools. Therefore, this paper seeks to examine the encounter between the Ottoman officialdom and the American Protestant missionaries in Ottoman Turkey during the successive regimes of Sultan Abdülhamid II and the Committee of Union and Progress, the Unionists in the period of 1876-1914. -

Eliza and John Taylor Jones in Siam (1833-1851)

Among a people of unclean lips : Eliza and John Taylor Jones in Siam (1833-1851) Autor(en): Trakulhun, Sven Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Asiatische Studien : Zeitschrift der Schweizerischen Asiengesellschaft = Études asiatiques : revue de la Société Suisse-Asie Band (Jahr): 67 (2013) Heft 4: Biography Afield in Asia and Europe PDF erstellt am: 10.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-391496 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch AMONG A PEOPLE OF UNCLEAN LIPS: ELIZA AND JOHN TAYLOR JONES IN SIAM 1833–1851) Sven Trakulhun, University of Zurich Abstract John Taylor Jones 1802–1851) and his first wife, Eliza Grew Jones 1803–1838), were the first American Baptist missionaries working in Siam during the reign of King Rama III. -

Timeline of Great Missionaries

Timeline of Great Missionaries (and a few other well-known historical and church figures and events) Prepared by Doug Nichols, Action International Ministries August 12, 2008 Dates Name Ministry/Place of Ministry 70-155/160 Polycarp Bishop of Smyrna 354-430 Aurelius Augustine Bishop of Hippo (Africa) 1235-1315 Raymon Lull Scholar and missionary (North Africa) 1320-1384 John Wyclif Morning Star of Reformation 1373-1475 John Hus Reformer 1483-1546 Martin Luther Reformation (Germany) 1494-1536 William Tyndale Bible Translator (England) 1509-1564 John Calvin Theologian/Reformation 1513-1573 John Knox Scottish Reformer 1517 Ninety-Five Theses (nailed) Martin Luther 1605-1690 John Eliot To North American Indians 1615-1691 Richard Baxter Puritan Pastor (England) 1628-1688 John Bunyan Pilgrim’s Progress (England) 1662-1714 Matthew Henry Pastor and Bible Commentator (England) 1700-1769 Nicholaus Ludwig Zinzendorf Moravian Church Founder 1703-1758 Jonathan Edwards Theologian (America) 1703-1791 John Wesley Methodist Founder (England) 1714-1770 George Whitefield Preacher of Great Awakening 1718-1747 David Brainerd To North American Indians 1725-1760 The Great Awakening 1759-1833 William Wilberforce Abolition (England) 1761-1834 William Carey Pioneer Missionary to India 1766-1838 Christmas Evans Wales 1768-1837 Joshua Marshman Bible Translation, founded boarding schools (India) 1769-1823 William Ward Leader of the British Baptist mission (India) 1773-1828 Rev. George Liele Jamaica – One of first American (African American) missionaries 1780-1845 -

Mission Strategies of Early Nineteenth-Century Missionary Wives in Burma and Hawaii

Evangelist or Homemaker? Mission Strategies of Early Nineteenth-Century Missionary Wives in Burma and Hawaii Dana Robert ne of the hallmarks of American Protestant mission sionary movement over the role of the missionary wife was the O work abroad has been its inclusion of women from the product of the experiences of missionaries in specific contexts, beginning. When the first five men commissioned by the Ameri not merely a reflection of stateside arguments over domesticity can Board departed for Indiain 1812,three wereaccompaniedby and women's spheres. their wives. The inclusion of women in the mission force, albeit In order to demonstrate how context and mission structure as "assistant missionaries," was a startling departure from the impacted the emerging theories and practice of American mis usual American idea that a missionary was a loner like David sionary wives, a comparison will be made of antebellum women Brainerd, bereft of family for the efficiency of the mission work. missionaries in Burma (Myanmar) and the Sandwich Islands Despite the public outcry against the horrible dangers that pre (Hawaii). Burma and the Sandwich Islands were the most suc sumably awaited them, Ann Judson, Roxana Nott, and Harriet cessful mission fields respectively of the American Baptists and Newell took their places in the pioneer group of foreign mission the American Board (Congregationalists and Presbyterians) in aries from the United States. the early nineteenth century. Both fields experienced mass con Not only was opinion divided over whether women should versions of tribal jungle peoples. The roles played by the Baptist be permitted to go to the mission field, but arguments continued and Congregational women, however, differed in the two con for forty years over the proper role of the missionary wife. -

The India Alliance, January 1914

The India Alliance. -- VOL. XIII.] JANUARY, 1914. [No. 7. "IT MATTERS TO HIM ABOUT YOU." I PET.5, 7. ( Literal Translation ). God's promise to greet me this New Year's day ! And one that never can pass away, Since it comes from Him who is faithful and true- Listen ! " It matters to Him about you." It matters to Him-what a restful thought, That God's own Son hath Salvation wrought So perfect, there's nothing for me to do But trust His, "matters to Him about you." Behind in the past are the last year's cares, It's failures, temptations, and subtle snares ; I'm glad the future is not in view, Only His "matters to Him about you." They are gone-let them go, we will fling away The mistakes and failures of yesterday ; Begin again with my Lord in view, And His promise " It matters to Him about you." I mean to trust Him as never before, And prove His promises more and rnore ; What matters though money and friends be few, I'll remember " It matters to Him about you." I need Him more as the years go by, With a great eternity drawing nigh ; But I have no fears, for real and true Is the promise " It matters to Him about you." So now " I will trust and not be afraid," But forward go with a lifted head And a trusting heart, ~hilefrom heaven's blue Falls sweetly " It matters to Him about you." I've a wonderful Saviour, Friend and Guide, Who has promised never to leave my side, But lead me straight all my life path through- Here and there " It matters to Him about you !" LAURAA. -

Mandalay and Printing Press Industry.Pdf

Title Mandalay and the Printing Industry All Authors Yan Naing Lin Local Publication Publication Type Publisher (Journal name, Mandalay University Researh Journal, Vol. 7 issue no., page no etc.) Literature, a kind of aesthetic art, is an effective tool for enlightenment, entertainment and propagation. It also reveals the politics, economy, social conditions and cultural aspects of certain period. Likewise, the books distribute the religious, political and cultural ideologies throughout the world. The books play a crucial role in the history of human innovations. The invention of printing press is the most important milestone to distribute various literary works and scientific knowledge. Since the last days of the monarchical rule, King Mindon who realized the importance of literature in propagation of Buddhism and wellbeing of kingdom included the foundation of printing industry in his reformation works. He published the first newspaper of Mandalay to counterpoise the propagation of British from Lower Myanmar. Abstract However, the printing industry of Mandalay in the reigns of King Mindon and King Thibaw was limited in the Buddhist cultural norms and could not provided the knowledge of the people. During the colonial period, the printing industry of Mandalay transformed into the tool to boost the knowledge and nationalist sentiment of people. The Wunthanu movement, nationalist movement, anti-colonialist struggle and struggle for independence under the AFPFL leadership as well as the struggle for peace in post independence era in Upper Myanmar were instigated by the Mandalay printing industry. Nevertheless, the printing industry of Mandalay was gradually on the wane under Revolutionary Council Government which practiced strict censorship on the newspapers and other periodicals. -

In One Sacred Effort – Elements of an American Baptist Missiology

In One Sacred Effort Elements of an American Baptist Missiology by Reid S. Trulson © Reid S. Trulson Revised February, 2017 1 American Baptist International Ministries was formed over two centuries ago by Baptists in the United States who believed that God was calling them to work together “in one sacred effort” to make disciples of all nations. Organized in 1814, it is the oldest Baptist international mission agency in North America and the second oldest in the world, following the Baptist Missionary Society formed in England in 1792 to send William and Dorothy Carey to India. International Ministries currently serves more than 1,800 short- term and long-term missionaries annually, bringing U.S. and Puerto Rico churches together with partners in 74 countries in ministries that tell the good news of Jesus Christ while meeting human needs. This is a review of the missiology exemplified by American Baptist International Ministries that has both emerged from and helped to shape American Baptist life. 2 American Baptists are better understood as a movement than an institution. Whether religious or secular, movements tend to be diverse, multi-directional and innovative. To retain their character and remain true to their core purpose beyond their first generation, movements must be able to do two seemingly opposite things. They must adopt dependable procedures while adapting to changing contexts. If they lose the balance between organization and innovation, most movements tend to become rigidly institutionalized or to break apart. Baptists have experienced both. For four centuries the American Baptist movement has borne its witness within the mosaic of Christianity. -

HBU Academy – 1St Place Winner-Piece of the Past Essay Contest, 2020

HBU Academy – 1st place winner-Piece of the Past Essay Contest, 2020 A Threefold Legacy: How Adoniram Judson’s Wives Contributed to the Ministry of the Man Who First Translated the Bible for the Burmese People by Rebecca Rizzotti In a glass case in the Dunham Bible Museum sits a book, open to public eye, filled seemingly with mere curves and squiggles. To an uninformed passerby, it may appear a simple curiosity, yet there is a story of incredible suffering, perseverance, and patience behind that book. It is a Burmese Bible. Adoniram Judson, as the first missionary sent out from the United States to a foreign country and the first person to translate the Bible into Burmese, is a well-known figure in the annals of missions. Yet in the many biographies, narratives, and articles centering on his life and work, the lives and work of his three wives—especially the latter two—are often overlooked. Each woman contributed immensely to a different aspect of his service that was essential to success as a missionary. Ann Hasseltine Judson demonstrated an incredible spirit of self-sacrifice during her marriage to Adoniram—first in agreeing to leave her family and homeland for a future of sickness and suffering, just days after their wedding in 1812—but most especially during her husband’s twenty-one months in brutal Burmese prisons in 1824-1825, his punishment for the false charge of espionage as he ministered in Rangoon. She “saved Judson’s life during the prison years… several times…Ann loved him fiercely, unreservedly, even to the point of giving her life for him. -

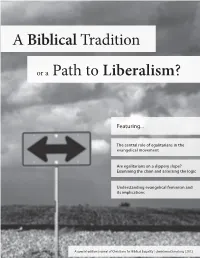

Or a Path to Liberalism? a Biblical Tradition

A Biblical Tradition or a Path to Liberalism? Featuring... The central role of egalitarians in the evangelical movement Are egalitarians on a slippery slope? Examining the claim and assessing the logic Understanding evangelical feminism and its implications A special edition journal of Christians for Biblical Equality | cbeinternational.org | 2013 A Biblical Tradition, or a Path to Liberalism? is a special edition journal published by Christians for Biblical Equality and distributed at the expense of Christians for Biblical Equality, © 2013. 122 West Franklin Avenue, Suite 218, Minneapolis, MN Contents 55404-2451, phone: 612-872-6898; fax: 612-872-6891; or email: [email protected]. CBE is on the web at www.cbeinternational.org. We welcome comments, article 3 Editor’s Reflections submissions, and advertisements. Tim Krueger Editors Tim Krueger and William D. Spencer 4 A Forum of Sensible Voices: 19th Century Associate Editor Deb Beatty Mel Forerunners of Evangelical Egalitarianism Editorial Consultant Aída Besançon Spencer Brandon G. Withrow President / Publisher Mimi Haddad 8 Egalitarians: A New Path to Liberalism? Or Integral to Board of Reference: Miriam Adeney, Carl E. Armerding, Evangelical DNA? Myron S. Augsburger, Raymond J. Bakke, Anthony Campolo, Mimi Haddad Lois McKinney Douglas, Gordon D. Fee, Richard Foster, John R. Franke, W. Ward Gasque, J. Lee Grady, Vernon 17 Egalitarianism as a Slippery Slope? Grounds†, David Joel Hamilton, Roberta Hestenes, Gretchen Stephen R. Holmes Gaebelein Hull, Donald Joy, Robbie Joy, Craig S. Keener, John R. Kohlenberger III, David Mains, Kari Torjesen Malcolm, 19 Assessing Hierarchist Logic: Are Egalitarians Really on Brenda Salter McNeil, Alvera Mickelsen, Roger Nicole†, Virgil Olson†, LaDonna Osborn, T. -

Noncommercial-Sharealike 4.0 International License

Timeline: Thai Church History in Global Context 1 eThis timeline is available online at www.thaichurchhistory.com and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. It may be freely distributed in either electronic or print format, provided that the website address is retained in the footer of the document. The text of this outline may be used for ministry and educational purposes without requesting permission, but you may not charge money for this outline beyond the cost of reproduction. Event Date Description Italian traveler Ludovico di Varthima says that while he was in Bangladesh, he met Nestorian Christians in 1503 Nestorian merchants from Ayuthaya. There is no other evidence to confirm his Ayuthaya? report. Portugese seize island of 1511 Malacca Portugal Diplomatic 1517 Mission to Ayuthaya Martin Luther’s 95 theses were a list of objections to abuse and errors in the Martin Luther Nails 95 Catholic Church. His attack on indulgences stirred controversy and ignited the Theses to Wittenburg 1517 Protestant Reformation. Protestants arrive in Thailand about 300 years after the Castle Door Catholics. Portugese Community in 1538 Ayuthaya Catholic missionaries arrive in Ayuthaya under the 1567 patronage of the Portugese 1656- King Narai the Great 1688 French Jesuits Arrive in Monseigneur Pierre de la Motte-Lambert leads a small group of French Jesuits to 1662 Siam establish a mission in Ayuthaya during the reign of King Narai. French Catholics found the Seminary of Saint Joseph in Ayuthaya, in order to train Seminary of Saint Joseph 1665 priests from all the countries of the Southeast Asia. -

Full Text, a History of the Baptists, Thomas Armitage

A HISTORY OF THE BAPTISTS By Thomas Armitage THE AMERICAN BAPTISTS I. THE COLONIAL PERIOD. PILGRIMS AND PURITANS The passage of the Mayflower over the Atlantic was long and rough. Often before its bosom had been torn by keels seeking the golden fleece for kings, but now the kings themselves were on board this frail craft, bringing the golden fleece with them; and the old deep had all that she could do to bear this load of royalty safely over. Stern as she was, the men borne on her waves were sterner. More than a new empire was intrusted to her care, a new freedom. 'What ailed thee, O sea?' When this historic ship came to her moorings, not unlike the vessel tossed on Galilee, she was freighted with principles, convictions, institutions and laws. These should first govern a quarter of the globe here, and then go back to the Old World to effect its regeneration and shape its future. THE PILGRIMS knew not that the King of all men was so signally with them in the bark, and would send them forth as the fishers of Gennesaret were sent, on an errand of revolution. In intellect, conscience and true soul-greatness, these quiet founders of a new nation were highly gifted, so that song and story will send their names down to the end of time on the bead-roll of fame. The monarchs of the earth have already raised their crowns in reverence to their greatness, and they are canonized in the moral forces which impelled and followed them.