Fresco Painting, Its Art and Technique, with Special Reference to the Buono and Spirit Fresco Methods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 11 Painting

Chapter 11 Painting • Medium: material that pigments are suspended in • Binder: holds the particles together (glue) • Support: in painting what the artist paints on • Transparent: paint that can be seen through • Opaque: paint that cannot be seen through • Ground: primer used to even the surface of the support, even application • Solvent: thinner that allows for paint to flow easier 1. Painting as the ability to copy during the Middle Ages 2. La Pittura: personification of Painting 1. Why is this important? Title: The Art of Painting Source/Museum: Vault of the Main Room, Arezzo, Casa Vasari. Canali Photobank, Capriolo, Italy. Artist: Giorgio Vasari Medium: Fresco Date: 1542 Size: n/a La Pintura 1. Representation 1. Herself 2. La Pittura 1. Why this representation? 2. Pendent: symbol of imitation 3. Accurate representation 1. Representation of nature through artist eyes 4. Portrayal 1. Real women 2. Idealized personification 5. Copy work or creative? 6. Equal to Leonardo and Michelangelo? 7. Western Painting: Painting the Nature 1. Zeuxius Vs. Parrhasius 1. Zeuxius: paints grapes and birds come down to eat them 2. Parrhasius: paints a curatian and Zeuxius asks him to remove the curtain so he can see the painting Title: Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting Source/Museum: The Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II. Artist: Artemisia Gentileschi Medium: Oil on canvas Date: 1630 Size: 35 ¼ x 29 in. Encaustic Encaustic Encaustic 1. Combining pigment with binder of hot wax 2. Funerary portraiture from Faiyum 60 miles South of Cairo 3. Real person 1. Naturalistic sensitive depiction of the face Source/Museum: Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York. -

The Secrets of Fresco Painting in the Italian Renaissance Art 2

1 ...the secrets of fresco painting in the Italian Renaissance Art 2 A PROJECT FOR A UNIQUE EXHIBITION The Renaissance greatest masters : Giotto, Beato Angelico, Botticelli, Michelangelo, Raffaello, Leonardo..... are brought together in this special exhibition by a leading thread : the art of fresco painting. In the spotlight of the exhibition are the unique frescoes created in Antonio De Vito’s Florentine atelier, telling us the intriguing and spectacular story of the art of the fresco. De Vito's own interpretations of the works of these immense artists guide us to the discovery of their secrets. The exhibition offers a path that leads visitors to the discovery not only of the technical aspects of fresco painting, but also of the artistic concepts characteristic of the Renaissance. The uniqueness of this project lies in the fact that it presents real frescoes, detached from the walls with a special technique, giving the visitors the opportunity to see works that traditionally can be admired only on the spot where they were painted. 3 THE EXHIBITION Our project provides a variable number of fresco paintings depending on the available space. Preparatory cartoons and sketches will be displayed with some of the works. Each fresco is displayed with caption and photographs. The initial section displays a rich gallery of frescoes, supported by an introduction to the technique of fresco painting with texts, photographs and videos to illustrate the differents steps in painting. Besides the gallery, in a unique development, a second section offers an area set up full of various features recreating the atelier of a Renaissance painter. -

Voyage from Palermo to Venice

VOYAGE FROM PALERMO TO VENICE Exploring the Historic Cities and Art Treasures of the Ionian & Adriatic Seas Aboard the 24-cabin Yacht Elysium With archaeologist Ivancica Schrunk May 21 – 31, 2022 Dear Traveler, Archaeological Institute of America ˆ ˆ Next spring, we invite you to join AIA lecturer and host Ivancica (Vanca) Schrunk LECTURER AND HOST aboard the private, yacht-like Elysium on a purpose-designed voyage from Sicily to Venice by way of Montenegro and Croatia, discovering historical gems of the Mediterranean, Ionian, and Adriatic Seas. The combination of fascinating history and sublime beauty is what makes these shorelines among the most spectacular places in the world. Consider Sicily’s Taormina, whose ancient Greek theater gazes at massive Mount Etna; the remarkable trulli villages of Italy’s Puglia region; the old, picturesque town of Kotor, nested at the head of a long, scenic bay; the beautifully preserved medieval city of Dubrovnik, overlooking the sparkling waters of the Adriatic; Split’s enormous Palace of Diocletian, one of the finest Roman monuments to survive from antiquity; the small town of Porec in Croatia’s Istria, home to the 6th-century Basilica of Euphrasius with its gleaming Byzantine mosaics; and Venice, our last stop and unquestionably one of the world’s most stunning and influential cities. Born in Zagreb, Croatia, AIA lecturer and host Vancǎ Schrunk will enrich your travel experience and understanding of the ancient and medieval history of this region through an onboard series of stimulating lectures as well as informal discussions. In addition, excellent local guides will accompany you on excursions throughout ˆ the program. -

Kayla Sprague Catalog Essay the Triumph of Death in Palermo the Triumph of Death Is a Grand Fresco That Was Commissioned For

Kayla Sprague Catalog Essay The Triumph of Death in Palermo The Triumph of Death is a grand fresco that was commissioned for the Sclafani Plazza in 1446. There is little information on the artist and the patron. The Triumph of Death in Palermo was painted in the late Gothic style, a century after the Black Death. It became a popular artistic theme across Europe during the 14th and 15th century and was a successful tool in terrifying people about the plague. The Triumph of Death was commonly recognized in that no description or text were necessary. 1 Unlike previous medieval paintings, the “Triumph” paintings did not inspire faith, however, the graphic images were instead used with intent to redirect panic from the plague and subtly scare people into paying attention to religion.2 The paintings were commissioned for hospitals and cemeteries and served as a warning that the alive were being judged by the dead; people should be careful not to sin for they would suffer as a result of the plague. The belief of the cause of the plague impacted what artists depicted in their paintings and gradually affected future iconography. The scene depicted in The Triumph of Death in Palermo, which can be analyzed in 6 parts, is located in a garden surrounded by a hedge, with groups of people cluttering the edges of the painting. In the center, a skeleton, personifying “Death” and riding an emaciated horse, interrupts the scene, carrying a scythe and shooting arrows from a bow. At the top left a man walks two dogs on taut leashes, one of the dogs appearing disturbed and growling and the other sniffing the hedge. -

The Drawings of Girolamo Romanino. Part IT

Originalveroffentlichung in: Burlington Magazine 137, Mai 1995, S, 300-306 ALESSANDRO NOVA The drawings of Girolamo Romanino. Part IT 11. Pyramus and Thisbe, by Girolamo Romanino. Pen and brown ink, 14 by 16.6 cm. (Louvre, Paris). 3 PREPARATORY drawings by Romanino for surviving paint Palazzo Martinengo in the via delle Cossere in Brescia, a ings he executed during the last thirty years of his career are palace once owned by Leonardo III Martinengo delle Palle 1 not numerous, but some of his late sheets provide important who died in 1536. Panazza listed this cycle among Romani 1 evidence about various lost works. no's lost works, and all subsequent scholars have taken this to After completing his frescoes for Cardinal Clesio at Trent, be the case. Yet, while three of the lunettes have lost all trace Romanino returned to Brescia in 1532. It remains contro of their frescoes, one contains three barely visible heads, and versial exactly which paintings can be dated to the early the central lunette retains the image of a woman holding a 1530s, but it is possible that a drawing now in the Louvre stick with which she apparently threatens two unidentified 1 (Fig. 11) belongs to these years. The spirited style of this figures. It is impossible to establish whether any of these sketch in pen and brown ink is similar to that of the drawings lunettes did indeed contain a fresco of Pyramus and Thisbe, executed during his Trentine period, and the theme of Pyra but the surviving fragment was probably executed around mus and Thisbe - first identified by Creighton Gilbert — was 1532-34, a perfectly acceptable date for the drawing in the 6 often represented by early sixteenth-century German artists, Louvre. -

Ann O'hanlon's Kentucky Mural Harriet W

The Kentucky Review Volume 8 | Number 1 Article 4 Spring 1988 Ann O'Hanlon's Kentucky Mural Harriet W. Fowler University of Kentucky Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review Part of the Art and Design Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Fowler, Harriet W. (1988) "Ann O'Hanlon's Kentucky Mural," The Kentucky Review: Vol. 8 : No. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review/vol8/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Kentucky Libraries at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Kentucky Review by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ann O'Hanlon's Kentucky Mural Harriet W. Fowler Over fifty years after its creation, the University of Kentucky's Memorial Hall mural, a Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) fresco by Ann Rice O'Hanlon, remains virtually unchanged from the time it was painted. Its colors have not lost their jewel-like tonalities, and its multi-layered composition is still crisply delineated.1 Completed in 1934 for the PWAP, the mural represents a pictorial history of important central Kentucky events and landmarks. It admirably fulfills the directive of its New Deal sponsors to document "the American Scene," a task which O'Hanlon, a then-recent graduate of the university, adapted to the local scene as she also wove autobiographical and poetic elements into the rich narrative of central Kentucky history. -

Renaissance on the Beach” Epitomized by 16Th Century Fresco at Sale E Pepe®, Marco Island, Fla

“Renaissance on the beach” epitomized by 16th century fresco at Sale e Pepe®, Marco Island, Fla. MARCO ISLAND, Fla. (February 24, 2006) — At Sale e Pepe on Marco Island, Southwest Florida’s quintessentially authentic Italian restaurant, nothing evokes “renaissance on the beach” as well as the 12-foot high hand-painted replica of a 416-year old masterpiece by Jacopo Zucchi, artist in residence to the Medici court, chief assistant for Vatican decorations, and honored with preparing the funeral decorations for Michelangelo. Zucchi’s original fresco, located in the Palazzo Ruspoli in Rome, inspired contemporary artist Rossen Tonkov, commissioned by Sale e Pepe’s owners, because of its large scale and grandeur as well as its powerful symbolic imagery depicting the constant balance of church and state power, an eternal Italian theme. Aesthetically, the fresco’s colors and shapes complement the restaurant’s intricate mosaic floors, carved marble detailing, historic Italian tapestries and paintings, and 400-year-old antiques. The final affect is a vision of an ancient seaside Italian restaurant. Tonkov, a Bulgarian native, was struck by the beauty of the palette used in the interior design of Sale e Pepe—stones, fabrics and fine objects – and the golden travertine walls providing the backdrop to the masterpiece. The fresco depicts a regal and impressive woman, papal crown in one hand, and the crown of the emperor of Rome in the other, commanding the focal point of the restaurant and looking out over the grotto-like intimate dining alcoves that distinguish Sale e Pepe’s formal dining area. Rossen Tonkov especially appreciated that his chosen image adhered to his golden rule—that a piece of art provide a minimum of seven different views in order to enrich a space. -

Artful Adventures Ancient Rome

Artful Adventures ANCIENT ROMEAn interactive guide for families 56 Your Roman Adventure Awaits You! W HSee inside for details ANCIENT ROME Today we are going to go on a pretend journey to Ancient Rome. We will travel back in time almost 3,000 years. Rome was the longest continuous empire in human history, lasting 1,200 years, from 753 B.C. to 476 A.D. At its height it spanned an area from present-day England to Iraq. The Roman Empire was powerful and wealthy. Roman leaders built large architectural structures, such as palaces, temples, and tombs, and decorated them lavishly with sculptures, mosaics, and J paintings. Amazingly, many of these works have survived. We are very fortunate to have some of these objects at the Princeton University Art Museum. By examining these ancient treasures, we can learn about what life was like in Ancient Rome. The Roman gallery is on the lower level of the museum. Walk down the stairs and turn to your right. Then make a left and walk through the doorway into the Roman gallery. G MOSAICS The mosaics in this gallery come from Antioch-on-the-Orontes. Today this area is part of Turkey, but in the third century A.D. it was a large, wealthy Roman city in Syria. Mosaics are made of tiny pieces of stone or glass, called tesserae, that are put together like a puzzle to create a picture or design. C The Romans used mosaics to decorate the floors of their homes the way we use carpets. The mosaics you see came from a villa in Antioch that was buried for more than a thousand years. -

St. Francis Appearing to a Pope and King Pen and Brown Ink and Brown Wash, Over Traces of an Underdrawing in Black Chalk

Pietro NOVELLI (Monreale 1603 - Palermo 1647) St. Francis Appearing to a Pope and King Pen and brown ink and brown wash, over traces of an underdrawing in black chalk. Inscribed fori(?) no. 42- on the verso. 316 x 231 mm. (12 1/2 x 9 1/8 in.) Drawn in the artist’s very distinctive pen manner, this drawing is a study, with several significant differences, for Monrealese’s painting of Saint Louis of France Receiving the Franciscan Girdle from Saint Francis, painted between 1635 and 1637, in the church of Santa Maria di Monte Oliveto (better known as the Badia Nuova) in Palermo. The altarpiece, which has undergone some repainting and has additions on three sides, differs from the drawing in several respects, particularly in the disposition of the figures. As such the present sheet must represent an early stage in the preparatory process. A variant or copy of this drawing is in the collection of the Galleria Regionale della Sicilia in Palermo. Monrealese had painted the same subject a few years earlier for another Franciscan church, San Francesco d’Assisi in Palermo. The fresco, destroyed in the Palermo earthquake of March 1823, is recorded in an engraving published two years earlier, in 1821. Some elements of the present sheet excluded from the Badia Nuova altarpiece, such as the soldier at the right, may be found in the composition of the lost fresco, which was, however, horizontal in format. Provenance: Anonymous sale, London, Sotheby’s, 11 June 1981, lot 108 Dr. G.A. Ricci, Rome Anonymous sale, London, Sotheby’s, 18 April 1994, lot 59 P. -

A Life Fresco: Enzo Ferroni (1921–2007)

202 International Journal of Ecodynamics. Vol. 2, No. 3 (2007) A LIFE FRESCO: ENZO FERRONI (1921–2007) Enzo Ferroni, chemist: born Florence 25 March 1921; Professor, Physical Chemistry, University of Florence 1965–96 (Emeritus), Rector 1976–79; President, Italian Centre for Colloids and Surfaces (CSGI) 1993–2006; President (twice), Italian Society of Physical Chemistry. Walther Hermann Nernst, the great German scientist, Nobel laureate in Chemistry, father of the third principle of thermodynamics, had a Florentine disciple, Giorgio Piccardi, later professor of Physical Chemistry at the University of Florence. Piccardi studied fluctuating phenomena before Ilya Prigogine and his best scholar and scientific successor was Enzo Ferroni who, when Piccardi retired, held the chair of Physical Chemistry at the University of Florence. Ferroni was also director of the Department of Chemistry and full professor of Physical Chemistry at the University of Cagliari (Sardinia). One of the authors of this article (E.T.) had the honor to be a student of Giorgio Piccardi, Enzo Ferroni and Ilya Prigogine. Enzo Ferroni died in a Florentine hospital on the 9 April 2007 at the age of eighty-six, after several years of failing health and much pain. Ferroni was born in Florence on 25 March 1921 and was educated at the Royal University of Florence where he took his ‘Dottore’ degree in Chemistry ‘Magna cum Laude’ (full marks and honours). There, soon after World War II, he reorganized the laboratories and served as teacher and instructor. Yet Ferroni was either an unsalaried or an unassuming man. He knew his subject well and knew how to pass on his knowledge to others; his practical classes were a model and his technique impeccable. -

The Art of Venice

The Art of Venice Justina Yee National Gallery of Art How was Venetian Renaissance art and its legacy distinct from Central Italy? • Venice’s geo-political stability and aesthetic diversity • “Pictorial Poetry”: landscape as narrative and use of oil • Disegno vs. Colorito: truth vs. myth • Titian’s long career and legacy “Mundus Alter” – Petrarch Jacopo de’ Barbari, Bird’s eye view of Venice, c.1500, printed from a six-piece woodcut Italy’s city-states during the Renaissance Egnazio Danti, Venice, 1580- 81, Fresco Moretto da Brescia, Portrait of a Lady in White, c. 1540 Sebastian del Piombo, Cardinal Bandinello Sauli, His Secretary, and Two Geographers, 1516 Giovanni Bellini and Titian, The Feast of the Gods, 1514/1529 Giorgione, The Adoration of the Shepherds, 1505/1510 Giorgione or Titian, Pastoral Concert c. 1510 (detail) Manet, Le Dejeuner sur l’herbe, 1863 Giorgione, The Tempest, c. 1506 Titian, Assumption of the Virgin, c. 1516 “Frari” (Basilica di Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari) Titian, Doge Andrea Gritti, 1546/1548 Titian, Portrait of a Lady, c. 1555 Ghirlandaio, Lucrezia Sommariac, c. 1510 Titian, Venus with Mirror, c. 1555 Disegno vs. Colorito Titian concealed “under the charm of his colors his poor knowledge of how to draw.” -Giorgio Vasari (Lives of the Artists, c. 1568) “No one [was] superior to Titian because of prowess in draftsmanship.” - Ludovico Dolce (Dialogo della Pittura, 1557) Titian, Group of Trees, c. 1514 Titian, Studies for Averoldi Polyptych, c. 1520 Titian, Averoldi Polyptych, c. 1520-22, Church of Santi Nazaro e Celso, Brescia xxx Francesco Maria della Rovere, Duke of Urbino, 1536 (drawing), 1536-38 (painting) Titian, St. -

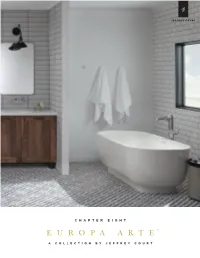

E U R O P a a R

CHAPTER EIGHT EUROPA ARTE® A COLLECTION BY JEFFREY COURT THE INSPIRATION CRAFT MAKES OUR HOMES MORE HUMAN. “ - ILSE CRAWFORD — Chapter 8 Europa Arte® is a diverse collection of their work or rich handmade textures representative of European-made ceramic and porcelain tiles. As the the soft indentations made by hand pressing clay. The name Arte in Europa Arte suggests, the themes carried solid Acquerello fields found in the collection maintain on by this collection revolve around art forms from an effect of gently laid watercolors while the patterned a wide array of mediums including clay, paints, and tiles take on the look of traditional cement encaustics. textiles. All points of inspiration used by traditional Cielo — Italian and Spanish artisans to create their unique Europa Arte’s hand-made look maintains the perfect 6” x 6” Verona Field Tile (80641) handcrafted masterpieces. Together, these elements balance of texture and color to create unparalleled Please Note: make up the motif of this colorful and multifaceted designs. All product shots are artistic interpretations of actual product. Due to the nature of the printing process, we chapter. recommend obtaining physical samples of product for actual color representation. Chapter 8 Europa Arte was designed to have shade variation and character associated with handmade products. Care should be taken to blend product from multiple cartons and product should be laid out prior to installation The field tiles featured in Chapter 8 have varied to ensure a proper, uniform look. A high-quality white thinset should also be used during installation. finishes ranging from subtle textures that simulate the delicate brushstrokes a painter would impress onto Please visit JeffreyCourt.com for additional installation and application details.