SIR TIM RICE Interviewed by Daniel Hahn DH

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

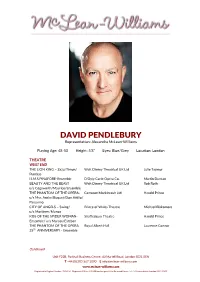

DAVID PENDLEBURY Representation: Alexandra Mclean-Williams

DAVID PENDLEBURY Representation: Alexandra McLean-Williams Playing Age: 48-58 Height: 5’8” Eyes: Blue/Grey Location: London THEATRE WEST END THE LION KING – Zazu/Timon/ Walt Disney Theatrical UK Ltd Julie Taymor Pumbaa H.M.S PINAFORE-Ensemble D’Oyly Carte Opera Co. Martin Duncan BEAUTY AND THE BEAST Walt Disney Theatrical UK Ltd Rob Roth u/s Cogsworth/Maurice/Ensemble THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA- Cameron Mackintosh Ltd Harold Prince u/s Msr. Andre/Buquet/Don Attilio/ Passarino CITY OF ANGELS – Swing/ Prince of Wales Theatre Michael Blakemore u/s Mortimer/Munoz KISS OF THE SPIDER WOMAN- Shaftesbury Theatre Harold Prince Ensemble/ u/s Marcos/Esteban THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA Royal Albert Hall Laurence Connor 25TH ANNIVERSARY - Ensemble Continued Unit F22B, Parkhall Business Centre, 40 Martell Road, London SE21 8EN T +44 (0) 203 567 1090 E [email protected] www.mclean-williams.com Registered in England Number: 7432186 Registered Office: C/O William Sturgess & Co, Burwood House, 14 - 16 Caxton Street, London SW1H 0QY DAVID PENDLEBURY continued REGIONAL THEATRE & TOURS – UK AND INTERNATIONAL SWEENEY TODD – Judge Turpin English Theatre, Frankfurt Derek Anderson/Lee Crowley HELLO AGAIN – The Senator Union Theatre Paul Callen/Henry Brennan/ Genevieve Lenney NICE WORK IF YOU CAN GET IT - Ovation John Plews/Grant Murphy Cookie McGee INTO THE WOODS – Steward AllStar Productions/Trilby Productions Tim McArthur THE PRODUCERS – Mr Marks China Tour/Selladoor Tara Wilkinson ME AND MY GIRL – Sir Jasper Tring Kilworth House Theatre Mitch Sebastian LITTLE -

EARLY MORNING and AFTER SCHOOL CLUBS Summer Term 2021

Founded 1936 EARLY MORNING and AFTER SCHOOL CLUBS Summer Term 2021 Early Morning Clubs start at 8am After School Clubs finish at 4.15pm Clubs will commence on Wednesday 21st April and finish on Thursday 1st July 2021 The online booking system will open on Monday 15th March at 9.30am and close on Friday 19th March 2021 at 4pm after this no further changes can be accommodated. If your child wishes to attend Early Morning or After School Clubs for the Summer Term 2021, please book online via the SchoolBase portal https://schoolbase.online Please note that all Clubs need a minimum number of 6 children attending to make them viable and are limited to a maximum number of children. Once the Clubs are full you will be placed on a waiting list. Parents will be informed as soon as possible if a Club is not able to go ahead. Bookings for AM Sports Academy clubs (AMSA) (Chess, Cricket, Football, Gymnastics and Multi- Sports) are made direct with them via their website: (www.amsportsacademy.co.uk/Clubs). If you have any questions please email them direct at: [email protected] Bookings for Sean McInnes Early Morning Clubs (Cricket, Football, and Tennis) are to be made direct through his website: https://seanmcinnessportscoaching.com/book-now If you have any questions please email Sean direct at: [email protected] Bookings for Mandarin are to be made direct by contacting Jing You at: [email protected] or by telephone: 07738696965 Piano & Violin Lessons Piano and Violin lessons are available during the week on a rotational basis, so that your child will not miss the same school lesson each week. -

Senior Musical Theater Recital Assisted by Ms

THE BELHAVEN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC Dr. Stephen W. Sachs, Chair presents Joy Kenyon Senior Musical Theater Recital assisted by Ms. Maggie McLinden, Accompanist Belhaven University Percussion Ensemble Women’s Chorus, Scott Foreman, Daniel Bravo James Kenyon, & Jessica Ziegelbauer Monday, April 13, 2015 • 7:30 p.m. Belhaven University Center for the Arts • Concert Hall There will be a reception after the program. Please come and greet the performers. Please refrain from the use of all flash and still photography during the concert Please turn off all cell phones and electronics. PROGRAM Just Leave Everything To Me from Hello Dolly Jerry Herman • b. 1931 100 Easy Ways To Lose a Man from Wonderful Town Leonard Bernstein • 1918 - 1990 Betty Comden • 1917 - 2006 Adolph Green • 1914 - 2002 Joy Kenyon, Soprano; Ms. Maggie McLinden, Accompanist The Man I Love from Lady, Be Good! George Gershwin • 1898 - 1937 Ira Gershwin • 1896 - 1983 Love is Here To Stay from The Goldwyn Follies Embraceable You from Girl Crazy Joy Kenyon, Soprano; Ms. Maggie McLinden, Accompanist; Scott Foreman, Bass Guitar; Daniel Bravo, Percussion Steam Heat (Music from The Pajama Game) Choreography by Mrs. Kellis McSparrin Oldenburg Dancer: Joy Kenyon He Lives in You (reprise) from The Lion King Mark Mancina • b. 1957 Jay Rifkin & Lebo M. • b. 1964 arr. Dr. Owen Rockwell Joy Kenyon, Soprano; Belhaven University Percussion Ensemble; Maddi Jolley, Brooke Kressin, Grace Anna Randall, Mariah Taylor, Elizabeth Walczak, Rachel Walczak, Evangeline Wilds, Julie Wolfe & Jessica Ziegelbauer INTERMISSION The Glamorous Life from A Little Night Music Stephen Sondheim • b. 1930 Sweet Liberty from Jane Eyre Paul Gordon • b. -

Audience Insights Table of Contents

GOODSPEED MUSICALS AUDIENCE INSIGHTS TABLE OF CONTENTS JUNE 29 - SEPT 8, 2018 THE GOODSPEED Production History.................................................................................................................................................................................3 Synopsis.......................................................................................................................................................................................................4 Characters......................................................................................................................................................................................................5 Meet the Writer........................................................................................................................................................................................6 Meet the Creative Team.......................................................................................................................................................................7 Director's Vision......................................................................................................................................................................................8 The Kids Company of Oliver!............................................................................................................................................................10 Dickens and the Poor..........................................................................................................................................................................11 -

Hw Biography 2021

HUGH WOOLDRIDGE Director and Lighting Designer; Visiting Professor Hugh Wooldridge has produced, directed and devised theatre and television productions all over the world. He has taught and given master-classes in the UK, Europe, the US, South Africa and Australia. He trained at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art (LAMDA) and made his West End debut as an actor in The Dame of Sark with Dame Celia Johnson. Subsequently he performed with the London Festival Ballet / English National Ballet in the world premiere production of Romeo and Juliet choreographed by Rudolph Nureyev. At the age of 22, he directed The World of Giselle for Dame Ninette de Valois and the Royal Ballet. Since this time, he has designed lighting for new choreography with dance companies around the world including The Royal Ballet, Dance Theatre London, Rambert Dance Company, the National Youth Ballet and the English National Ballet Company. He directed the world premieres of the Graham Collier / Malcolm Lowry Jazz Suite Under A Volcano and The Undisput’d Monarch of the English Stage with Gary Bond portraying David Garrick; the Charles Strouse opera, Nightingale with Sarah Brightman at the Buxton Opera Festival; Francis Wyndham’s Abel and Cain (Haymarket, Leicester) with Peter Eyre and Sean Baker. He directed and lit the original award-winning Jeeves Takes Charge at the Lyric Hammersmith; the first productions of the Andrew Lloyd Webber and T. S. Eliot Cats (Sydmonton Festival), and the Andrew Lloyd Webber / Don Black song-cycle Tell Me 0n a Sunday with Marti Webb at the Royalty (now Peacock) Theatre; also Lloyd Webber’s Variations at the Royal Festival Hall (later combined together to become Song and Dance) and Liz Robertson’s one-woman show Just Liz compiled by Alan Jay Lerner at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London. -

A Career Overview 2019

ELAINE PAIGE A CAREER OVERVIEW 2019 Official Website: www.elainepaige.com Twitter: @elaine_paige THEATRE: Date Production Role Theatre 1968–1970 Hair Member of the Tribe Shaftesbury Theatre (London) 1973–1974 Grease Sandy New London Theatre (London) 1974–1975 Billy Rita Theatre Royal, Drury Lane (London) 1976–1977 The Boyfriend Maisie Haymarket Theatre (Leicester) 1978–1980 Evita Eva Perón Prince Edward Theatre (London) 1981–1982 Cats Grizabella New London Theatre (London) 1983–1984 Abbacadabra Miss Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith Williams/Carabosse (London) 1986–1987 Chess Florence Vassy Prince Edward Theatre (London) 1989–1990 Anything Goes Reno Sweeney Prince Edward Theatre (London) 1993–1994 Piaf Édith Piaf Piccadilly Theatre (London) 1994, 1995- Sunset Boulevard Norma Desmond Adelphi Theatre (London) & then 1996, 1996– Minskoff Theatre (New York) 19981997 The Misanthrope Célimène Peter Hall Company, Piccadilly Theatre (London) 2000–2001 The King And I Anna Leonowens London Palladium (London) 2003 Where There's A Will Angèle Yvonne Arnaud Theatre (Guildford) & then the Theatre Royal 2004 Sweeney Todd – The Demon Mrs Lovett New York City Opera (New York)(Brighton) Barber Of Fleet Street 2007 The Drowsy Chaperone The Drowsy Novello Theatre (London) Chaperone/Beatrice 2011-12 Follies Carlotta CampionStockwell Kennedy Centre (Washington DC) Marquis Theatre, (New York) 2017-18 Dick Whttington Queen Rat LondoAhmansen Theatre (Los Angeles)n Palladium Theatre OTHER EARLY THEATRE ROLES: The Roar Of The Greasepaint - The Smell Of The Crowd (UK Tour) -

Stonyhurst Association Newsletter 306 July 2013

am dg Ston y hurSt GES RU 1762 . B .L 3 I 9 E 5 G 1 E S 1 R 7 7 E 3 M . O 4 T S 9 . 7 S 1 T O ST association news N YHUR STONYHURST newsletter 306 ASSOjulyC 2013IATION 1 GES RU 1762 . B .L 3 I 9 E G StonyhurSt association 5 1 E S 1 R 7 7 E 3 M . O 4 francis xavier scholarships T S 9 newsletter . 7 S 1 T O ST N YHUR The St Francis Xavier Award is a scholarship being awarded for entry to newSlet ter 306 a mdg july 2013 Stonyhurst. These awards are available at 11+ and 13+ for up to 10 students who, in the opinion of the selection panel, are most likely to benefitS from,T andO NYHURST contribute to, life as full boarders in a Catholic boarding school. Assessments for contentS the awards comprise written examinations and one or more interviews. diary of events 4 Applicants for the award are expected to be bright pupils who will fully participate in all aspects of boarding school life here at Stonyhurst. St Francis In memoriam 4 Xavier Award holders will automatically benefit from a fee remissionA of 20%S andS OCIATION thereafter may also apply for a means-tested bursary, worth up to a further 50% Congratulations 5 off the full boarding fees. 50 years ago 6 The award is intended to foster the virtues of belief, ambition and hard work which Francis Xavier exemplified in pushing out the boundaries of the Christian reunions 7 faith. -

Do You Think You're What They Say You Are? Reflections on Jesus Christ Superstar

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 3 Issue 2 October 1999 Article 2 October 1999 Do You Think You're What They Say You Are? Reflections on Jesus Christ Superstar Mark Goodacre University of Birmingham, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf Recommended Citation Goodacre, Mark (1999) "Do You Think You're What They Say You Are? Reflections on Jesus Christ Superstar," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 3 : Iss. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol3/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Do You Think You're What They Say You Are? Reflections on Jesus Christ Superstar Abstract Jesus Christ Superstar (dir. Norman Jewison, 1973) is a hybrid which, though influenced yb Jesus films, also transcends them. Its rock opera format and its focus on Holy Week make it congenial to the adaptation of the Gospels and its characterization of a plausible, non-stereotypical Jesus capable of change sets it apart from the traditional films and aligns it with The Last Temptation of Christ and Jesus of Montreal. It uses its depiction of Jesus as a means not of reverence but of interrogation, asking him questions by placing him in a context full of overtones of the culture of the early 1970s, English-speaking West, attempting to understand him by converting him into a pop-idol, with adoring groupies among whom Jesus struggles, out of context, in an alien culture that ultimately crushes him, crucifies him and leaves him behind. -

CATS • April 1-3, 2011 • TPAC’S Andrew Jackson Hall

OnStage The official playbill and performing arts magazine of the TENNESSEE PERFORMING ARTS CENTER HCA/TriStar Broadway at TPAC • TPAC Family Field Trip • TPAC Presents • TPAC’s Signature Series CATS • April 1-3, 2011 • TPAC’s Andrew Jackson Hall www.tpac.org POWERING YOUR family time u plugged It’s often said that there are no small parts. At First Tennessee, we believe that there are no small dreams either. That’s why we offer a wide-range of financial services designed to help your family enjoy more of the things that matter most. So whether you’re looking for a convenient checking account or help with a home loan, our friendly staff is always available to play a supporting role. Banking products and services provided by First Tennessee Bank National Association. Member FDIC. ©2009 First Tennessee Bank National Association. www.firsttennessee.com Sure, it’s just a tire. Like the ancient redwood is just a tree. bridgestonetire.com 1-800-807-9555 tiresafety.com 11bridge5056 Arts 7.125x10.875.indd 1 1/28/11 1:46:37 PM REPRESENTATIONAL PHOTO REPRESENTATIONAL hen we learned how sick Mom was, we didn’t know what Wto do. We’re so thankful that we asked her doctor about Alive Hospice. They came into our home like family, helping Mom stay with us where she wanted to be. 1718 Patterson Street | Nashville, TN 37203 615-327-1085 or 800-327-1085 | www.alivehospice.org We provide loving care to people with life-threatening illnesses, support to their families, and service to the community in a spirit of enriching lives. -

Dream Cast Announced for Disney's Aladdin

DREAM CAST ANNOUNCED FOR DISNEY’S ALADDIN An exceptional group of Australia and New Zealand’s most outstanding musical theatre performers and exciting fresh faces has been announced for Disney’s new musical comedy, Aladdin. They will be joined by Broadway performer Michael James Scott in the role of the Genie. Based on the classic Academy Award®-winning animated film,Aladdin will open in Sydney at the Capitol Theatre in August 2016. Tickets go on sale to the GP 8th March 2016. The dream cast for Aladdin has been achieved after intense and competitive auditions throughout Australia. It will be one of the most diverse multi-cultural casts to appear on the Australian stage. American performer Michael James Scott will play the pivotal role of the Genie. Michael has performed in many Broadway shows including the original company of The Book of Mormon, the 2010 Broadway and London revival of Hair, as well as the standby Genie in the original Broadway cast of Aladdin. He was most recently seen in Casey Nicholaw’s third current Broadway hit, Something Rotten. Joining him will be the exciting new discovery Ainsley Melham making his mainstage debut in the title role of Aladdin. Ainsley is a graduate of the Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts (WAAPA). The principal cast features international musical theatre star Adam Jon Fiorentino (Saturday Night Fever, Mary Poppins) as Kassim, stage & television performer Adam Murphy as Jafar and Robert Tripolino in the role of Omar. Filling out the principal ranks is one of Australia’s most accomplished character actors and musical theatre stars Troy Sussman as Babkak and stage and television actor Aljin Abella as Iago. -

Honours Thesis Game Theory and the Metaphor of Chess in the Late Cold

Honours Thesis Game Theory and the Metaphor of Chess in the late Cold War Period o Student number: 6206468 o Home address: Valeriaan 8 3417 RR Montfoort o Email address: [email protected] o Type of thesis/paper: Honours Thesis o Submission date: March 29, 2020 o Thesis supervisor: Irina Marin ([email protected]) o Number of words: 18.291 o Page numbers: 55 Abstract This thesis discusses how the game of chess has been used as a metaphor for the power politics between the United States of America and the Soviet Union during the Cold War, particularly the period of the Reagan Doctrine (1985-1989). By looking at chess in relation to its visual, symbolic and political meanings, as well in relation to game theory and the key concepts of polarity and power politics, it argues that, although the ‘chess game metaphor’ has been used during the Cold War as a presentation for the international relations between the two superpowers in both cultural and political endeavors, the allegory obscures many nuances of the Cold War. Acknowledgment This thesis has been written roughly from November 2019 to March 2020. It was a long journey, and in the end my own ambition and enthusiasm got the better of me. The fact that I did three other courses at the same time can partly be attributed to this, but in many ways, I should have kept my time-management and planning more in check. Despite this, I enjoyed every moment of writing this thesis, and the subject is still captivating to me. -

Australian Ephemera Collection Finding Aid

AUSTRALIAN EPHEMERA COLLECTION FINDING AID BARRY HUMPHRIES PERFORMING ARTS PROGRAMS AND EPHEMERA (PROMPT) PRINTED AUSTRALIANA JANUARY 2015 Barry Humphries was born in Melbourne on the 17th of February 1934. He is a multi-talented actor, satirist, artist and author. He began his stage career in 1952 in Call Me Madman. As actor he has invented many satiric Australian characters such as Sandy Stone, Lance Boyle, Debbie Thwaite, Neil Singleton and Barry (‘Bazza’) McKenzie but his most famous creations are Dame Edna Everage who debuted in 1955 and Sir Leslie (‘Les’) Colin Patterson in 1974. Dame Edna, Sir Les and Bazza between them have made several sound recordings, written books and appeared in films and television and have been the subject of exhibitions. Since the 1960s Humphries’ career has alternated between England, Australia and the United States of America with his material becoming more international. Barry Humphries’ autobiography More Please (London; New York : Viking, 1992) won him the J.R. Ackerley Prize in 1993. He has won various awards for theatre, comedy and as a television personality. In 1994 he was accorded an honorary doctorate from Griffith University, Queensland and in 2003 received an Honorary Doctorate of Law from the University of Melbourne. He was awarded an Order of Australia in 1982; a Centenary Medal in 2001 for “service to Australian society through acting and writing”; and made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire for "services to entertainment" in 2007 (Queen's Birthday Honours, UK List). Humphries was named 2012 Australian of the Year in the UK. CONTENT The Barry Humphries PROMPT collection includes programs, ephemera and newspaper cuttings which document Barry Humphries and his alter egos on stage in Australia and overseas from the beginning of his career in the 1950s into the 21st Century.