Read Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dido Reloaded / Go, Aeneas, Go! (Òpera Líquida De Cambra)

© Helena Moliné dido reloaded / go, aeneas, go! (òpera líquida de cambra) Òpera de Butxaca i Nova Creació temporada 2014/2015 www.teatrelliure.cat 1 Montjuïc Espai Lliure - del 26 al 30 de novembre Dido reloaded / Go, Aeneas, Go! (òpera líquida de cambra) Òpera de Butxaca i Nova Creació intèrprets Anna Alàs i Jové mezzo, Belinda i Europa / María Hinojosa soprano, Dido / Joan Ribalta tenor, Aeneas / clarinet Víctor de la Rosa / violoncel Cèlia Torres composició Xavier Bonfill, Raquel García-Tomás, Joan Magrané i Octavi Rumbau / dramatúrgia Cristina Cordero / direcció escènica Jordi Pérez Solé (La Mama Produccions) / direcció musical Francesc Prat escenografia Jorge Salcedo, Jordi Pérez Solé i Ulrike Reinhard / vestuari Isabel Velasco i Christina Kämper / caracterització Isabel Velasco i Anne-Claire Meyer / il·luminació Sylvia Kuchinow / vídeo Raquel García-Tomàs / moviment Anna Romaní i Èlia López / assessor dramatúrgic Marc Rosich ajudant d’escenografia Joana Martí / comunicació Neus Purtí / producció executiva Cristina Cordero / director de producció Dietrich Grosse coproducció Òpera de Butxaca i Nova Creació, Teatre Lliure, Neuköllner Oper i Berliner Opernpreis – GASAG amb el suport del Departament de Cultura de la Generalitat de Catalunya i l’Ajuntament de Barcelona agraïments Consolat d’Alemanya a Barcelona, Louise Higham, Helena Moliné i Paquita Crespo Go, Aeneas, Go! va ser guardonat amb el Berliner Opernpreis 14 von Neuköllner Oper und GASAG“, un premi berlinès dedicat a la nova creació operística i que dóna suport a creadors emergents perquè puguin produir una òpera a la Neuköllner Oper. espectacle multilingüe sobretitulat en català durada 1h. primera part / 15' pausa / 30' segona part / 10' epíleg seguiu #DidoAeneas al twitter horaris: de dimecres a divendres a les 21h. -

1. Lezione Di Acustica Forma D'onda, Frequenza, Periodo, Ampiezza

1. Lezione di acustica forma d’onda, frequenza, periodo, ampiezza, suoni periodici, altezza, ottava LA CATENA ACUSTICA Il suono è una sensazione uditiva provocata da una variazione della pressione dell’aria. L’onda sonora generata dalla vibrazione di un corpo elastico arriva al nostro orecchio dopo aver viaggiato lungo un altro materiale elastico (nella nostra esperienza più comune l’aria). Gli elementi necessari perché si verifichi un suono sono dunque tre: la sorgente sonora (il corpo vibrante) il mezzo di trasmissione dell’onda sonora (l’ambiente, anche non omogeneo, dove il suono si propaga) il ricevitore (l’ orecchio e il cervello) Della natura delle vibrazioni e delle onde sonore e della loro propagazione nel mezzo si occupa la acustica fisica, del rapporto tra onda sonora e il ricevente (il sistema orecchio – cervello), e quindi di come l’uomo interpreta i segnali acustici, si occupa la psicoacustica. VIBRAZIONE DI CORPI ELASTICI - MOTO ARMONICO SEMPLICE Alla base del comportamento di gran parte dei corpi vibranti degli strumenti musicali c’è il moto armonico semplice, un tipo di movimento oscillatorio che si ripete regolarmente e di cui possiamo calcolare il periodo, ossia la durata (sempre uguale) dei singoli cicli. Il moto armonico semplice si verifica quando un corpo dotato di massa, sottoposto a una forza (nel nostro caso di tipo elastico) oscilla periodicamente intorno a una posizione di equilibrio. Gli esempi più comunemente riportati nei libri di fisica sono quello del sistema massa-molla (una massa attaccata a una molla), e quello del pendolo. Molla Massa Per noi musicisti può essere più intuitivo pensare alla corda di una chitarra, adeguatamente tesa, fissata a due estremi: quando viene pizzicata al centro, si allontana fino a una distanza massima dalla posizione di equilibrio, quindi la tensione la riporta nella posizione iniziale, dopodiché, a causa dell’inerzia, prosegue il suo moto curvandosi nella direzione opposta (Pierce, fig. -

Gioachino Rossini the Journey to Rheims Ottavio Dantone

_____________________________________________________________ GIOACHINO ROSSINI THE JOURNEY TO RHEIMS OTTAVIO DANTONE TEATRO ALLA SCALA www.musicom.it THE JOURNEY TO RHEIMS ________________________________________________________________________________ LISTENING GUIDE Philip Gossett We know practically nothing about the events that led to the composition of Il viaggio a Reims, the first and only Italian opera Rossini wrote for Paris. It was a celebratory work, first performed on 19 June 1825, honoring the coronation of Charles X, who had been crowned King of France at the Cathedral of Rheims on 29 May 1825. After the King returned to Paris, his coronation was celebrated in many Parisian theaters, among them the Théâtre Italien. The event offered Rossini a splendid occasion to present himself to the Paris that mattered, especially the political establishment. He had served as the director of the Théatre Italien from November 1824, but thus far he had only reproduced operas originally written for Italian stages, often with new music composed for Paris. For the coronation opera, however, it proved important that the Théâtre Italien had been annexed by the Académie Royale de Musique already in 1818. Rossini therefore had at his disposition the finest instrumentalists in Paris. He took advantage of this opportunity and wrote his opera with those musicians in mind. He also drew on the entire company of the Théâtre Italien, so that he could produce an opera with a large number of remarkable solo parts (ten major roles and another eight minor ones). Plans for multitudinous celebrations for the coronation of Charles X were established by the municipal council of Paris in a decree of 7 February 1825. -

1 Prime+Trama TRAVIATA

Parma e le terre di Verdi 1-28 ottobre 2007 La Traviata Musica di GIUSEPPE VERDI Parma e le terre di Verdi 1-28 ottobre 2007 Parma e le terre di Verdi 1-28 ottobre 2007 main sponsor media partner Il Festival Verdi è realizzato anche grazie a e con il sostegno e la collaborazione di Teatro Verdi di Busseto Teatro Comunale di Modena iTeatri di Reggio Emilia Soci fondatori Consiglio di Amministrazione Presidente Pietro Vignali Sindaco di Parma Consiglieri Paolo Cavalieri Maurizio Marchetti Sovrintendente Mauro Meli Direttore musicale Bruno Bartoletti Segretario generale Gianfranco Carra Collegio dei Revisori Giuseppe Ferrazza Presidente Nicola Bianchi Andrea Frattini La Traviata Melodramma in tre atti su libretto di Francesco Maria Piave dal dramma La Dame aux camélias di Alexandre Dumas figlio Musica di GIUSEPPE V ERDI Editore Universal Music Publishing Ricordi srl, Milano Villa Verdi a Sant’Agata La trama dell’opera Atto primo Parigi, alla metà dell’Ottocento. È estate e c’è festa nella casa di Violetta Valéry, una famosa mondana: è un modo per soffocare l’angoscia che la tormenta, perché ella sa che la sua salute è gravemente minata. Un nobile, Gastone, presenta alla padrona di casa il suo amico Alfredo, che l’ammira sinceramente. L’attenzione che Violetta dimostra per la nuova conoscenza non sfugge a Douphol, il suo amante abituale. Mentre Violetta e Alfredo danzano, il giovane le dichiara tutto il suo amore e Violetta gli regala un fiore, una camelia: rivedrà Alfredo solo quando sarà appassita. Alla fine della festa, Violetta deve ammettere di essersi innamorata davvero, per la prima volta. -

The Magic Flute

The Magic Flute PRODUCTION INFORMATION Music: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Text (English): Emanuel Schikaneder English Translation: J.D. McClatchy World Premiere: Vienna, Theater auf der Wieden Austria, September 30, 1791 Final Dress Rehearsal Date: Friday, December 13, 2013 Note: the following times are approximate 10:30am – 12:30pm Cast: Pamina Heidi Stober Queen of the Night Albina Shagimuratova Tamino Alek Shrader Papageno Nathan Gunn Speaker Shenyang Sarastro Eric Owens Production Team: Conductor Jane Glover Production Julie Taymor Set Designer George Tsypin Costume Designer Julie Taymor Lighting Designer Donald Holder Puppet Designers Julie Taymor and Michael Curry Choreographer Mark Dendy 2 Table of Contents Production Information 2 An Introduction to Pathways for Understanding Study Materials 4 Meet the Characters 5 The Story of The Magic Flute Synopsis 6 Guiding Questions 8 The History of Mozart’s The Magic Flute 10 Guided Listening Overture 12 I’m sure that there could never be 13 Such loveliness beyond compare 14 Don’t be afraid, now hear my song 15 The wrath of hell is burning in my bosom 16 Now I know that love can vanish 17 If only I could meet her 18 Pa-pa-ge-na! – Pa-pa-ge-no! 19 The Magic Flute Resources About the Composer 20 The Enlightenment & Singspiel 22 Online Resources 25 Additional Resources The Emergence of Opera 26 Metropolitan Opera Facts 30 Reflections after the Opera 32 A Guide to Voice Parts and Families of the Orchestra 33 Glossary 34 References Works Consulted 38 3 An Introduction to Pathways for Understanding Study Materials The goal of Pathways for Understanding materials is to provide multiple “pathways” for learning about a specific opera as well as the operatic art form, and to allow teachers to create lessons that work best for their particular teaching style, subject area, and class of students. -

Arte Actress Revolutionized the Early Modern Italian Stage

How the COMMEDIA DELL’ARTE Actress Revolutionized the Early Modern Italian Stage Rosalind Kerr Summary: The first actresses who joined the previously all-male the commedia dell’Arte in the 1560s are credited with making it a commercial and artistic success. This article explores the evidence to document their multi-faceted contribution and influence on the birth of early modern European theatre. My article will use Tommaso Garzoni’s prophetic observations about certain early actresses to frame an inquiry into how their novel female presence changed the nature of theatrical representation to create a new more “realistic” medium. It will interpret the documents to reveal how they achieved celebrity status through the great personal appeal and technical mastery they exhibited. It was through this winning combination that they were empowered to create unforgettable female characters who became part of the western dramatic canon. In addition to showing how successfully the Italian actresses challenged masculine privilege in their famous transvestite performances, I will show how their iconic influence travelled not only across the continent but also to England, even though actresses remained excluded from the professional stage there. Inevitably their presence on the western stage provided examples of female characters negotiating their sex/gender identities and thus modeled such behaviours for women in the larger society. Tommaso Garzoni in his giant compendium, La piazza universale di tutte le professioni del mondo (1585), noted that a few outstanding actresses were the saving grace in lifting this dubious profession from its buffoonish roots to a respectable art form.1 The praise he lavished on four female performers: Isabella Andreini, Vincenza Armani, Lidia da Bagnacavallo, and Vittoria Piissimi singles out their great beauty and eloquence to explain how they captivated their audiences. -

11 May 2008 Waterford Institute Of

Society for Musicology in Ireland Annual Conference 9 – 11 May 2008 Waterford Institute of Technology (College Street Campus) Waterford Institute of Technology welcomes you to the Sixth Annual Conference of the Society for Musicology in Ireland. We are particularly delighted to welcome our distinguished keynote speaker, Professor John Tyrrell from Cardiff University. Programme Committee Dr. Hazel Farrell Dr. David J. Rhodes (Chair) Conference Organisation Fionnuala Brennan Paddy Butler Jennifer Doyle Dr. Hazel Farrell Marc Jones Dr. Una Kealy Dr. David J. Rhodes Technician: Eoghan Kinane Acknowledgements Dr. Gareth Cox Dr. Rachel Finnegan, Head of the Department of Creative and Performing Arts, WIT Norah Fogarty Dr. Michael Murphy Professor Jan Smaczny Waterford Crystal WIT Catering Services Exhibition Four Courts Press will be exhibiting a selection of new and recent books covering many areas from ancient to twenty-first century music, opera, analysis, ethnomusicology, popular and film music on Saturday 10 May Timetable Humanities & Art Building: Room HA06 Room HA07 Room HA08 Room HA17 (Auditorium) Main Building (Ground floor): Staff Room Chapel Friday 9 May 1.00 – 2.00 Registration (Foyer of Humanities & Art Building) 2.00 – 3.30 Sessions 1 – 3 Session 1 (Room HA06): Nineteenth-century Reception and Criticism Chair: Lorraine Byrne Bodley (National University of Ireland Maynooth) • Adèle Commins (Dundalk Institute of Technology): Perceptions of an Irish composer: reception theories of Charles Villiers Stanford • Aisling Kenny (National -

09-25-2019 Macbeth.Indd

GIUSEPPE VERDI macbeth conductor Opera in four acts Marco Armiliato Libretto by Francesco Maria Piave production Adrian Noble and Andrea Maffei, based on the play by William Shakespeare set and costume designer Mark Thompson Wednesday, September 25, 2019 lighting designer 8:00–11:10 PM Jean Kalman choreographer Sue Lefton First time this season The production of Macbeth was made possible by a generous gift from Mr. and Mrs. Paul M. Montrone Additional funding was received from Mr. and Mrs. William R. Miller; Hermione Foundation, Laura Sloate, Trustee; and The Gilbert S. Kahn & John J. Noffo Kahn Endowment Fund Revival a gift of Rolex general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2019–20 SEASON The 106th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIUSEPPE VERDI’S macbeth conductor Marco Armiliato in order of appearance macbeth fle ance Plácido Domingo Misha Grossman banquo a murderer Ildar Abdrazakov Richard Bernstein l ady macbeth apparitions Anna Netrebko a warrior Christopher Job l ady-in-waiting Sarah Cambidge DEBUT a bloody child Meigui Zhang** a servant DEBUT Bradley Garvin a crowned child duncan Karen Chia-Ling Ho Raymond Renault DEBUT a her ald malcolm Yohan Yi Giuseppe Filianoti This performance is being broadcast a doctor macduff live on Metropolitan Harold Wilson Matthew Polenzani Opera Radio on SiriusXM channel 75. Wednesday, September 25, 2019, 8:00–11:10PM MARTY SOHL / MET OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Verdi’s Macbeth Assistants to the Set Designer Colin Falconer and Alex Lowde Assistant to the Costume Designer Mitchell Bloom Musical Preparation John Keenan, Yelena Kurdina, Bradley Moore*, and Jonathan C. -

CAPITOLO 11 Acustica Della Voce

CAPITOLO 11 Acustica della voce Mauro Uberti Da Acustica musicale e architettonica a cura di SERGIO CINGOLANI e RENATO SPAGNOLO UTET libreria, Torino, 2005 11.1 Generalità La voce è il suono prodotto dalla vibrazione di due strutture muscolari poste nel collo, dette corde vocali, messe in vibrazione dall'aria espirata dai polmoni; es- so è poi modulato timbricamente dalle risonanze delle due cavità che compon- gono il canale vocale: la faringe e la bocca. Per semplicità si può scomporre il fenomeno vocale in tre momenti distinti: la produzione del fiato, la generazione del suono e la modulazione di questo. Le tre funzioni coinvolgono l'apparato respiratorio e la parte superiore di quello di- gestivo (organi della masticazione e della deglutizione): il primo è responsabile della produzione del fiato e della generazione del suono, il secondo della mo- dulazione del timbro vocale e dell'articolazione della parola. In realtà la fona- zione, l'insieme, cioè, delle funzioni fisiologiche che intervengono nella produ- zione della voce, è un'attività che coinvolge direttamente o indirettamente tutto il corpo. La postura, per esempio, influisce sulla geometria dello scheletro e quindi sulla meccanica respiratoria. Influiscono pure sulla stessa le condizioni di ripienezza dell'apparato digerente e così via. Di converso le manovre artico- latorie e di produzione del suono interagiscono con la meccanica respiratoria inducendo inoltre cambiamenti nell'equilibrio e nella postura. Gli organi direttamente impegnati nella formazione del suono vocale hanno tutti funzioni primarie diverse da quella di generare la voce e il loro impiego nella fonazione è un adattamento secondario. Quello responsabile della produ- zione del suono, la laringe, per quanto già più o meno sviluppato in tutti i Te- trapodi (animali a quattro zampe), presenta la sua massima evidenza nei Mam- miferi (Baldaccini et al., 1996). -

Donizetti Il Duca D’Alba

Gaetano Donizetti Il Duca d’Alba Il duca d’Alba - F. Goya - 1795 Huile sur toile ; 195 x 126 - Madrid, Museo del Prado « J’avais surtout caressé le rôle (1) de la femme ; rôle nouveau peut-être au théâtre, un rôle d’action, tandis que presque toujours la femme est passive. Ici, une jeune enthousiaste, aimante, une Jeanne d’Arc. » Gaetano Donizetti, janvier 1842 (1) en français dans le texte Ces quelques mots de Donizetti nous donnent non seulement sa conception de cette héroïne hors du commun, mais révèlent combien il tenait encore à l’œuvre, trois années après le début de la composition de son opéra… qu’il n’achèvera pourtant jamais car malheureusement pour l’Art, le personnage - tout particulier qu’il est, précisément ! - déplaît à la divette régnant alors sur l’Opéra de Les dossiers de Forum Opéra - www.forumopera.com - Il duca d'Alba © Yonel Buldrini - p. 1 Paris (et son directeur). Il sera tout de même créé, mais après quarante années d’attente et quelques essais infructueux. L’actuelle reprise, motivant cet article, aura lieu dans le cadre de la Saison lyrique de Radio France, le 15 avril 2005 *, et il pourrait bien s’agir de la création en France, pays auquel était destiné l’opéra ! En raison de la grève d'une partie des personnels de Radio France, le concert du vendredi 15 avril, au programme duquel était inscrit Il Duca d'Alba de Donizetti, est annulé. (Ndlr) Donizetti et Le Duc d’Albe « Addio mia Bella Napoli ! » Ces premiers mots d’une mélancolique chanson populaire, par la voix tremblotante et nasillarde de Caruso, sortant des impressionnants pavillons des phonographes, pourraient nous donner l’état d’esprit avec lequel Donizetti quitte la Naples de ses succès. -

One of Opera's Greatest Hits! Teacher's Guide and Resource Book

One of opera’s greatest hits! Teacher’s Guide and Resource Book 1 Dear Educator, Welcome to Arizona Opera! We are thrilled that you and your students are joining us for Rigoletto, Verdi’s timeless, classic opera. At Arizona Opera, we strive to help students find and explore their voices. We believe that providing opportunities to explore the performing arts allows students to explore the world around them. Rigoletto is a great opera to introduce students to the world of opera. By preparing them for this opera, you are setting them up to get the most out of their experience of this important, thrilling work. This study guide is designed to efficiently provide the information you need to prepare your students for the opera. At the end of this guide, there are a few suggestions for classroom activities that connect your students’ experience at the opera to Arizona College and Career Ready Standards. These activities are designed for many different grade levels, so please feel free to customize and adapt these activities to meet the needs of your individual classrooms. Parking for buses and vans is provided outside Symphony Hall. Buses may begin to arrive at 5:30pm and there will be a preshow lecture at 6:00pm. The performance begins at 7:00pm. Again, we look forward to having you at the opera and please contact me at [email protected] or at (602)218-7325 with any questions. Best, Joshua Borths Education Manager Arizona Opera 2 Table of Contents About the Production Audience Etiquette: Attending the Opera……………………………………………………………Pg. -

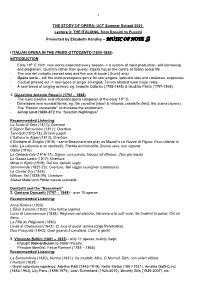

1 the STORY of OPERA: UCT Summer School 2021: Lecture 3

1 THE STORY OF OPERA: UCT Summer School 2021: Lecture 3: THE ITALIANS, from Rossini to Puccini Presented by Elizabeth Handley – MUSIC OF NOTE ♫ I ITALIAN OPERA IN THE PRIMO OTTOCENTO (1800-1850) INTRODUCTION - Early 19th C ItalY: new works expected every season -> a system of rapid production, self-borrowing and plagiarism. Quantity rather than quality. Opera house the centre of Italian social life. - The aria del sorbetto (sorbet aria) and the aria di baule ( [trunk] aria). - Opera seria – still the most prestigious genre for star singers: splendid sets and costumes, expensive. - Castrati phased out -> new types of singer emerged. Tenors allotted more major roles. - A new breed of singing actress, eg. Isabella Colbran (1785-1845) & Giuditta Pasta (1797-1865). 1. Gioachino Antonio Rossini (1792 – 1868) - The most creative and influential opera composer of the early 19th C. - Developed new musical forms, eg. the cavatina (slow) & virtuosic cabaletta (fast); the scena (scene). - The “Rossini crescendo”: to increase the excitement. - Jenny Lind (1820-87): the “Swedish Nightingale”. Recommended Listening: La Scala di Seta (1812): Overture Il Signor Beruschino (1812): Overture Tancredi (1812-13): Di tanti palpiti L’Italiana in Algeri (1813): Overture Il Barbiere di Siviglia (1816) - same Beaumarchais play as Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro: Ecco ridente in cielo, La calunnia e un venticello, Fredda ed immobile, Buona sera, mio signore Otello (1816) La Cenerentola (1816-17): Signor, una parola, Nacqui all’affanno...Non piu mesta La Gazza Ladra (1817): Overture Mosè in Egito (1818): Dal tuo stellato soglo Semiramide (1822-23): Overture, Bel raggio lusinghier (coloratura) Le Comte Ory (1828) William Tell (1828-29): Overture Stabat Mater and Petite messe solonelle Donizetti and the “Rossiniani” 2.