Newsletter of Sep

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taxonomy and New Records of Graphidaceae Lichens in Western Pangasinan, Northern Philippines

PRIMARY RESEARCH PAPER | Philippine Journal of Systematic Biology DOI 10.26757/pjsb2019b13006 Taxonomy and new records of Graphidaceae lichens in Western Pangasinan, Northern Philippines Weenalei T. Fajardo1, 2* and Paulina A. Bawingan1 Abstract There are limited studies on the diversity of Philippine lichenized fungi. This study collected and determined corticolous Graphidaceae from 38 collection sites in 10 municipalities of western Pangasinan province. The study found 35 Graphidaceae species belonging to 11 genera. Graphis is the dominant genus with 19 species. Other species belong to the genera Allographa (3 species) Fissurina (3), Phaeographis (3), while Austrotrema, Chapsa, Diorygma, Dyplolabia, Glyphis, Ocellularia, and Thelotrema had one species each. This taxonomic survey added 14 new records of Graphidaceae to the flora of western Pangasinan. Keywords: Lichenized fungi, corticolous, crustose lichens, Ostropales Introduction described Graphidaceae in the country (Parnmen et al. 2012). Most recent surveys resulted in the characterization of six new Graphidaceae is the second largest family of lichenized species (Lumbsch et al. 2011; Tabaquero et al.2013; Rivas-Plata fungi (Ascomycota) (Rivas-Plata et al. 2012; Lücking et al. et al. 2014). In the northwestern part of Luzon in the Philippines 2017) and is the most speciose of tropical crustose lichens (Region 1), an account on the Graphidaceae lichens was (Staiger 2002; Lücking 2009). The inclusion of the initially conducted only from the Hundred Islands National Park (HINP), separate family Thelotremataceae (Mangold et al. 2008; Rivas- Alaminos City, Pangasinan (Bawingan et al. 2014). The study Plata et al. 2012) in the family Graphidaceae made the latter the reported 32 identified lichens, including 17 Graphidaceae dominant element of lichen communities with 2,161 accepted belonging to the genera Diorygma, Fissurina, Graphis, Thecaria species belonging to 79 genera (Lücking et al. -

Cryptic Species and Species Pairs in Lichens: a Discussion on the Relationship Between Molecular Phylogenies and Morphological Characters

cryptic species:07-Cryptic_species 10/12/2009 13:19 Página 71 Anales del Jardín Botánico de Madrid Vol. 66S1: 71-81, 2009 ISSN: 0211-1322 doi: 10.3989/ajbm.2225 Cryptic species and species pairs in lichens: A discussion on the relationship between molecular phylogenies and morphological characters by Ana Crespo & Sergio Pérez-Ortega Departamento de Biología Vegetal II, Facultad de Farmacia, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, E-28040 Madrid, Spain [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Resumen Crespo, A. & Pérez-Ortega, S. 2009. Cryptic species and species Crespo, A. & Pérez-Ortega, S. 2009. Especies crípticas y pares de pairs in lichens: A discussion on the relationship between mole- especies en líquenes: una discusión sobre la relación entre la fi- cular phylogenies and morphological characters. Anales Jard. logenia molecular y los caracteres morfológicos. Anales Jard. Bot. Madrid 66S1: 71-81. Bot. Madrid 66S1: 71-81 (en inglés). As with most disciplines in biology, molecular genetics has re- Como en otras disciplinas, el impacto producido por la filogenia volutionized our understanding of lichenized fungi. Nowhere molecular en el conocimiento de los hongos liquenizados ha has this been more true than in systematics, especially in the de- producido avances y cambios conceptuales importantes. Esto limitation of species. In many cases, molecular research has ve- ha sido especialmente cierto en la sistemática y ha afectado de rified long-standing hypotheses, but in others, results appear to una manera muy notable en aspectos -

Annotated Check List and Host Index Arizona Wood

Annotated Check List and Host Index for Arizona Wood-Rotting Fungi Item Type text; Book Authors Gilbertson, R. L.; Martin, K. J.; Lindsey, J. P. Publisher College of Agriculture, University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ) Rights Copyright © Arizona Board of Regents. The University of Arizona. Download date 28/09/2021 02:18:59 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/602154 Annotated Check List and Host Index for Arizona Wood - Rotting Fungi Technical Bulletin 209 Agricultural Experiment Station The University of Arizona Tucson AÏfJ\fOTA TED CHECK LI5T aid HOST INDEX ford ARIZONA WOOD- ROTTlNg FUNGI /. L. GILßERTSON K.T IyIARTiN Z J. P, LINDSEY3 PRDFE550I of PLANT PATHOLOgY 2GRADUATE ASSISTANT in I?ESEARCI-4 36FZADAATE A5 S /STANT'" TEACHING Z z l'9 FR5 1974- INTRODUCTION flora similar to that of the Gulf Coast and the southeastern United States is found. Here the major tree species include hardwoods such as Arizona is characterized by a wide variety of Arizona sycamore, Arizona black walnut, oaks, ecological zones from Sonoran Desert to alpine velvet ash, Fremont cottonwood, willows, and tundra. This environmental diversity has resulted mesquite. Some conifers, including Chihuahua pine, in a rich flora of woody plants in the state. De- Apache pine, pinyons, junipers, and Arizona cypress tailed accounts of the vegetation of Arizona have also occur in association with these hardwoods. appeared in a number of publications, including Arizona fungi typical of the southeastern flora those of Benson and Darrow (1954), Nichol (1952), include Fomitopsis ulmaria, Donkia pulcherrima, Kearney and Peebles (1969), Shreve and Wiggins Tyromyces palustris, Lopharia crassa, Inonotus (1964), Lowe (1972), and Hastings et al. -

Global Biodiversity Patterns of the Photobionts Associated with the Genus Cladonia (Lecanorales, Ascomycota)

Microbial Ecology https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-020-01633-3 FUNGAL MICROBIOLOGY Global Biodiversity Patterns of the Photobionts Associated with the Genus Cladonia (Lecanorales, Ascomycota) Raquel Pino-Bodas1 & Soili Stenroos2 Received: 19 August 2020 /Accepted: 22 October 2020 # The Author(s) 2020 Abstract The diversity of lichen photobionts is not fully known. We studied here the diversity of the photobionts associated with Cladonia, a sub-cosmopolitan genus ecologically important, whose photobionts belong to the green algae genus Asterochloris. The genetic diversity of Asterochloris was screened by using the ITS rDNA and actin type I regions in 223 specimens and 135 species of Cladonia collected all over the world. These data, added to those available in GenBank, were compiled in a dataset of altogether 545 Asterochloris sequences occurring in 172 species of Cladonia. A high diversity of Asterochloris associated with Cladonia was found. The commonest photobiont lineages associated with this genus are A. glomerata, A. italiana,andA. mediterranea. Analyses of partitioned variation were carried out in order to elucidate the relative influence on the photobiont genetic variation of the following factors: mycobiont identity, geographic distribution, climate, and mycobiont phylogeny. The mycobiont identity and climate were found to be the main drivers for the genetic variation of Asterochloris. The geographical distribution of the different Asterochloris lineages was described. Some lineages showed a clear dominance in one or several climatic regions. In addition, the specificity and the selectivity were studied for 18 species of Cladonia. Potentially specialist and generalist species of Cladonia were identified. A correlation was found between the sexual reproduction frequency of the host and the frequency of certain Asterochloris OTUs. -

The Mycological Society of San Francisco • Jan. 2016, Vol. 67:05

The Mycological Society of San Francisco • Jan. 2016, vol. 67:05 Table of Contents JANUARY 19 General Meeting Speaker Mushroom of the Month by K. Litchfield 1 President Post by B. Wenck-Reilly 2 Robert Dale Rogers Schizophyllum by D. Arora & W. So 4 Culinary Corner by H. Lunan 5 Hospitality by E. Multhaup 5 Holiday Dinner 2015 Report by E. Multhaup 6 Bizarre World of Fungi: 1965 by B. Sommer 7 Academic Quadrant by J. Shay 8 Announcements / Events 9 2015 Fungus Fair by J. Shay 10 David Arora’s talk by D. Tighe 11 Cultivation Quarters by K. Litchfield 12 Fungus Fair Species list by D. Nolan 13 Calendar 15 Mushroom of the Month: Chanterelle by Ken Litchfield Twenty-One Myths of Medicinal Mushrooms: Information on the use of medicinal mushrooms for This month’s profiled mushroom is the delectable Chan- preventive and therapeutic modalities has increased terelle, one of the most distinctive and easily recognized mush- on the internet in the past decade. Some is based on rooms in all its many colors and meaty forms. These golden, yellow, science and most on marketing. This talk will look white, rosy, scarlet, purple, blue, and black cornucopias of succu- at 21 common misconceptions, helping separate fact lent brawn belong to the genera Cantharellus, Craterellus, Gomphus, from fiction. Turbinellus, and Polyozellus. Rather than popping up quickly from quiescent primordial buttons that only need enough rain to expand About the speaker: the preformed babies, Robert Dale Rogers has been an herbalist for over forty these mushrooms re- years. He has a Bachelor of Science from the Univer- quire an extended period sity of Alberta, where he is an assistant clinical profes- of slower growth and sor in Family Medicine. -

Lavansaari) – One of the Remote Islands in the Gulf of Finland

Folia Cryptog. Estonica, Fasc. 56: 31–52 (2019) https://doi.org/10.12697/fce.2019.56.05 The lichens of Moshchny Island (Lavansaari) – one of the remote islands in the Gulf of Finland Irina S. Stepanchikova1,2, Dmitry E. Himelbrant1,2, Ulf Schiefelbein3, Jurga Motiejūnaitė4, Teuvo Ahti5, Mikhail P. Andreev2 1St. Petersburg State University, Universitetskaya emb. 7–9, 199034 St. Petersburg, Russia. E-mails: [email protected], [email protected] 2Laboratory of Lichenology and Bryology, Komarov Botanical Institute RAS, Professor Popov St. 2, 197376 St. Petersburg, Russia. E-mail: [email protected] 3Blücherstrasse 71, D-18055 Rostock, Germany. E-mail: [email protected] 4Laboratory of Mycology, Institute of Botany, Nature Research Centre, Žaliųjų Ežerų 49, LT–08406 Vilnius, Lithuania. E-mail: [email protected] 5Botanical Museum, Finnish Museum of Natural History, University of Helsinki, P.O. Box 7, FI-00014 Helsinki, Finland. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: We present a checklist for Moshchny Island (Leningrad Region, Russia). The documented lichen biota comprises 349 species, including 313 lichens, 30 lichenicolous fungi and 6 non-lichenized saprobic fungi. Endococcus exerrans and Lichenopeltella coppinsii are reported for the first time for Russia;Cercidospora stenotropae, Erythricium aurantiacum, Flavoplaca limonia, Lecidea haerjedalica, and Myriospora myochroa for European Russia; Flavoplaca oasis, Intralichen christiansenii, Nesolechia fusca, and Myriolecis zosterae for North-Western European Russia; and Arthrorhaphis aeruginosa, Calogaya pusilla, and Lecidea auriculata subsp. auriculata are new for Leningrad Region. The studied lichen biota is moderately rich and diverse, but a long history of human activity likely caused its transformation, especially the degradation of forest lichen biota. -

Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve Management Plan 2011-2016

Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve Management Plan 2011-2016 April 1981 Revised, May 1982 2nd revision, April 1983 3rd revision, December 1999 4th revision, May 2011 Prepared for U.S. Department of Commerce Ohio Department of Natural Resources National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Division of Wildlife Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management 2045 Morse Road, Bldg. G Estuarine Reserves Division Columbus, Ohio 1305 East West Highway 43229-6693 Silver Spring, MD 20910 This management plan has been developed in accordance with NOAA regulations, including all provisions for public involvement. It is consistent with the congressional intent of Section 315 of the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, as amended, and the provisions of the Ohio Coastal Management Program. OWC NERR Management Plan, 2011 - 2016 Acknowledgements This management plan was prepared by the staff and Advisory Council of the Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve (OWC NERR), in collaboration with the Ohio Department of Natural Resources-Division of Wildlife. Participants in the planning process included: Manager, Frank Lopez; Research Coordinator, Dr. David Klarer; Coastal Training Program Coordinator, Heather Elmer; Education Coordinator, Ann Keefe; Education Specialist Phoebe Van Zoest; and Office Assistant, Gloria Pasterak. Other Reserve staff including Dick Boyer and Marje Bernhardt contributed their expertise to numerous planning meetings. The Reserve is grateful for the input and recommendations provided by members of the Old Woman Creek NERR Advisory Council. The Reserve is appreciative of the review, guidance, and council of Division of Wildlife Executive Administrator Dave Scott and the mapping expertise of Keith Lott and the late Steve Barry. -

The Mycophile 52:2 March/April 2012

VOLUME 52:2 March-April 2012 www.namyco.org PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE by Bob Fulgency I am pleased to report that outstanding west coast in food establishments.” The growing problem of safety mycologist Dr. Tom Bruns has accepted an invitaon to associated with the unregulated sale of wild mushroom become a NAMA Ins:tu:onal Trustee. Tom is a to the public was what generated CFP’s interest. professor and associate chair at the Department of Plant and Microbial Biology at the University of California, The Commi`ee’s plan is to develop a blueprint that Berkeley, and he is a past president of the Mycological regulatory agencies can follow to allow them to exercise Society of America. He received an M.S. from the meaningful control over all facets of wild mushroom University of Minnesota and a Ph.D. from the University harves:ng and distribu:on. At this :me, the Commi`ee of Michigan. He has published over 120 ar:cles on fungal intends to submit five recommendaons to CFP for ecology and evolu:on and is best known for his work of consideraon. Of par:cular interest is the training of ectomycorrhizal communi:es. I know Tom will make approved mushroom iden:fiers. Based on this plan, each important contribu:ons to NAMA's ongoing mission of state or region will be expected to develop a list of suppor:ng the scien:fic study of fungi. mushrooms that can be collected in the area. Further, it will be responsible for training candidates and Issues surrounding regulatory oversight of wild subsequently test them for their knowledge of wild mushroom harves:ng and sale s:ll linger. -

New Data on the Occurence of an Element Both

Analele UniversităĠii din Oradea, Fascicula Biologie Tom. XVI / 2, 2009, pp. 53-59 CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE KNOWLEDGE DIVERSITY OF LIGNICOLOUS MACROMYCETES (BASIDIOMYCETES) FROM CĂ3ĂğÂNII MOUNTAINS Ioana CIORTAN* *,,Alexandru. Buia” Botanical Garden, Craiova, Romania Corresponding author: Ioana Ciortan, ,,Alexandru Buia” Botanical Garden, 26 Constantin Lecca Str., zip code: 200217,Craiova, Romania, tel.: 0040251413820, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. This paper presents partial results of research conducted between 2005 and 2009 in different forests (beech forests, mixed forests of beech with spruce, pure spruce) in CăSăĠânii Mountains (Romania). 123 species of wood inhabiting Basidiomycetes are reported from the CăSăĠânii Mountains, both saprotrophs and parasites, as identified by various species of trees. Keywords: diversity, macromycetes, Basidiomycetes, ecology, substrate, saprotroph, parasite, lignicolous INTRODUCTION MATERIALS AND METHODS The data presented are part of an extensive study, The research was conducted using transects and which will complete the PhD thesis. The CăSăĠânii setting fixed locations in some vegetable formations, Mountains are a mountain group of the ùureanu- which were visited several times a year beginning with Parâng-Lotru Mountains, belonging to the mountain the months April-May until October-November. chain of the Southern Carpathians. They are situated in Fungi were identified on the basis of both the SE parth of the Parâng Mountain, between OlteĠ morphological and anatomical properties of fruiting River in the west, Olt River in the east, Lotru and bodies and according to specific chemical reactions LaroriĠa Rivers in the north. Our area is 900 Km2 large using the bibliography [1-8, 10-13]. Special (Fig. 1). The vegetation presents typical levers: major presentation was made in phylogenetic order, the associations characteristic of each lever are present in system of classification used was that adopted by Kirk this massif. -

Scientific Name Common Name Status Agaricus Campestris

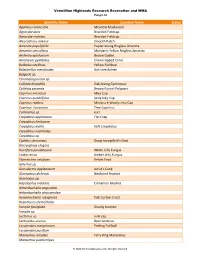

Vermillion Highlands Research Recreation and WMA Fungi List Scientific Name Common Name Status Agaricus campestris Meadow Mushroom Agrocybe dura Bearded Fieldcap Agrocybe molesta Bearded Fieldcap Aleurodiscus oakesii Smooth Patch Amanita populiphila Poplar-loving Ringless Amanita Amanita sinicoflava Mandarin Yellow Ringless Amanita Arrhenia epichysium Brown Goblet Artomyces pyxidatus Crown-tipped Coral Bolbitius vitellinus Yellow Fieldcap Boletinellus merulioides Ash-tree Bolete Bulgaria sp. Chromelosporium sp. Collybia dryophila Oak-loving Gymnopus Coltricia perennis Brown Funnel Polypore Coprinus micaceus Mica Cap Coprinus quadrifidus Scaly Inky Cap Coprinus radians Miniature Woolly Inky Cap Coprinus truncorum Tree Coprinus Cortinarius sp. cort Crepidotus applanatus Flat Crep Crepidotus herbarum Crepidotus mollis Soft Crepidotus Crepidotus nephrodes Crepidotus sp. Cyathus stercoreus Dung-loving Bird’s Nest Dacryopinax elegans Ductifera pululahuana White Jelly Fungus Exidia recisa Amber Jelly Fungus Flammulina velutipes Velvet Foot Galerina sp. Ganoderma applanatum Artist’s Conk Gloeoporus dichrous Bicolored Bracket Gymnopus sp. Hapalopilus nidulans Cinnamon Bracket Hohenbuehelia angustata Hohenbuehelia atrocaerulea Hymenochaete rubiginosa Oak Curtain Crust Hypomyces tremellicola Inocybe fastigiata Deadly Inocybe Inocybe sp. Lactarius sp. milk cap Lentinellus ursinus Bear Lentinus Lycoperdon marginatum Peeling Puffball Lycoperdon pusillum Marasmius oreades Fairy Ring Marasmius Marasmius pulcherripes © 2020 MinnesotaSeasons.com. All rights -

One Hundred and Seventy-Five New Species of Graphidaceae: Closing the Gap Or a Drop in the Bucket?

Phytotaxa 189 (1): 007–038 ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) www.mapress.com/phytotaxa/ Article PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2014 Magnolia Press ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.189.1.4 One hundred and seventy-five new species of Graphidaceae: closing the gap or a drop in the bucket? ROBERT LÜCKING1, MARK K. JOHNSTON1, ANDRÉ APTROOT2, EKAPHAN KRAICHAK1, JAMES C. LENDEMER3, KANSRI BOONPRAGOB4, MARCELA E. S. CÁCERES5, DAMIEN ERTZ6, LIDIA ITATI FERRARO7, ZE-FENG JIA8, KLAUS KALB9,10, ARMIN MANGOLD11, LEKA MANOCH12, JOEL A. MERCADO-DÍAZ13, BIBIANA MONCADA14, PACHARA MONGKOLSUK4, KHWANRUAN BUTSATORN PAPONG 15, SITTIPORN PARNMEN16, ROUCHI N. PELÁEZ14, VASUN POENGSUNGNOEN17, EIMY RIVAS PLATA1, WANARUK SAIPUNKAEW18, HARRIE J. M. SIPMAN19, JUTARAT SUTJARITTURAKAN10,18, DRIES VAN DEN BROECK6, MATT VON KONRAT1, GOTHAMIE WEERAKOON20 & H. THORSTEN 1 LUMBSCH 1Science & Education, The Field Museum, 1400 South Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, Illinois 60605-2496, U.S.A.; email: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] 2ABL Herbarium, G.v.d.Veenstraat 107, NL-3762 XK Soest, The Netherlands; email: [email protected] 3Institute of Systematic Botany, The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY 10458-5126, U.S.A.; email: [email protected] 4Lichen Research Unit, Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Ramkhamhaeng University, Ramkhamhaeng 24 road, Bangkok, 10240 Thailand; email: [email protected] 5Departamento de Biociências, Universidade Federal de Sergipe, CEP: 49500-000, -

Biodiversity of Dead Wood

Scottish Natural Heritage Biodiversity of Dead Wood Fungi – Lichens - Bryophytes Dr David Genney SNH Policy and Advice Officer Scottish Natural Heritage Key messages Scotland is home to thousands of fungi, lichens and bryophytes, many of which depend on dead wood as a food source or place to grow. This presentation gives a brief introduction, for each group, to the diversity of dead wood species and the types of dead wood they need to survive. The take-home message is that the dead wood habitat is as diverse as the species that depend upon it. Ensuring a wide range of these dead wood types will maximise species diversity. Some dead wood types need special management and may need to be prioritised in areas where threatened species depend upon them. Scottish Natural Heritage FUNGI Dead wood is food for fungi and they, in turn, have a big impact on its quality and ultimate fate With thousands of species, each with specific habitat requirements, fungi require a wide diversity of dead wood types to maximise diversity Liz Holden Scottish Natural Heritage Different fungi rot wood in different ways – the main types of rot are brown rot and white rot Brown rot fungi The main building block of wood, cellulose, is broken down by the fungi, but not other structural compounds such as lignin. Dead wood is brown and exhibits brick-like cracking Many bracket fungi are brown rotters Liz Holden Cellulose Scottish Natural Heritage White-rot fungi White-rot fungi degrade a wider range of wood compounds, including the very complex polymer, lignin Pale wood More species are white-rot than brown-rot fungi Lignin Liz Holden Lignin Scottish Natural Heritage Armillaria spp.