Romanticizing Poverty the Representation of African Countries by Western Development Organizations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Beyond Internationalization: Lessons from Post-Development

Peer-Reviewed Article © Journal of International Students Volume 11, Issue S1 (2021), pp. 133-151 ISSN: 2162-3104 (Print), 2166-3750 (Online) ojed.org/jis Beyond Internationalization: Lessons from Post-Development Kumari Beck Simon Fraser University, Canada ABSTRACT Despite the critiques generated in critical internationalization studies in response to the neoliberal and neocolonial orientation of internationalization of higher education, the direction of internationalization appears to be unchanged. This paper takes up the challenge of imagining internationalization otherwise by drawing from the field of post-development (PD) studies, which, it is argued, has parallels to the realities and debates on internationalization. An overview of the debates in PD and why they offer important ideas for critical internationalization studies will be followed by a discussion of how key analyses and arguments in PD can be applied to internationalization. This argument leads to the question of whether it is time to recognize an emerging post-internationalization movement, acknowledging that internationalization as we know it is in decline. The paper concludes with an exploration of a new commons in internationalization, refocusing on educational principles and values, while recognizing the complexities and contradictions inherent in seeking international education that is “in between, with and from multiple worlds.” Keywords: internationalization of higher education, international education, post- development, critical internationalization studies, new commons INTRODUCTION The last three decades have seen a rapid growth in the internationalization of higher education, which needs to be understood alongside the conditions of globalization and the consequential market orientation of higher education (Darder, 2016) and colonial contexts of history, culture and power (Dolby & Rahman, 2008). -

Group Protests Marine Presence , Qu.Wiidnesday, Jan

73. Vol. ,23, Issue 16 THE TRINITY February t£ 1975 Trinity College TRIPOD Hartford, Conn. Student Elections Fill 12 College Committees Student elections were held last Fred Lahey 55 Thursday, Jan. 30, in the lobby of Mather Policy Board (1) Mather Hall. Twenty-three Kim Jonas 28 (write-in* positions on 12 college committees Special Committee on FU»ap» were filled by the winning can- pointment, Tenure, and didates whose names and total Promotions (2) votes received appear below. Total Steve Kayman 127 voter turnout on election day was SheUa Driscoll 109 610. Student Activities Committee (3) Election Results Jim Cobbs 141 Academic Affairs Committee (1) Peter Pieragostini 141 Paul Sachs 176 Ramsay Gross 130 College Affairs Committee (1) Parking Appeals Board (3) Adrienne Mally 147 Stan Goldich 197 Curriculum Committee (1) Ralph Stone 172 Bill Levy 114 Craig Shields 156 Financial Affairs Committee (1) Studeiit Government Association Stan Goldich 159 Library Committee (1) Pat Heffernan 227 • George Stiffler 301 Sheila Driscoll 190 Mather Hall Board of Gover- Richard Chamberlain 140 nors— upperclass position (2) Barbara Husum 130 Mary Desmond 153 Bill O'Brien 117 Jay Morgan 148 Mather Hall Board of Gover- Trinity College Council (1) nors—freshman position (l) Mike Brown 19 (write-in) photo by Al Moore Reaction Mixed Group Protests Marine Presence , Qu.Wiidnesday, Jan. 29, an anti- hearing the parting words of a another location on campus. The tn&tmte {action led by Peter Jessop marine recruiter whom Margolis removal of the Marines might, '76 and John Bach, a 27 year old reported to have said, "I'll see you however, entail more than just a Hartford resident, distributed next year. -

Navigating Multiple Knowledge Systems and Responding to Climate Change in the Maldives Rachel Hannah Spiegel Pitzer College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pitzer Senior Theses Pitzer Student Scholarship 2017 Drowning in Rising Seas: Navigating Multiple Knowledge Systems and Responding to Climate Change in the Maldives Rachel Hannah Spiegel Pitzer College Recommended Citation Spiegel, Rachel Hannah, "Drowning in Rising Seas: Navigating Multiple Knowledge Systems and Responding to Climate Change in the Maldives" (2017). Pitzer Senior Theses. 76. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/pitzer_theses/76 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pitzer Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pitzer Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Drowning in Rising Seas: Navigating Multiple Knowledge Systems and Responding to Climate Change in the Maldives Rachel H. Spiegel In partial fulfillment of a Bachelor of Arts Degree in Environmental Analysis and International/Intercultural Studies April 2017 Pitzer College, Claremont, California Readers: Professor Joseph Parker and Professor Susan Phillips DROWNING IN RISING SEAS 1 Image: Maldivian Cabinet member and Minister of Fisheries & Agriculture Dr. Ibrahim Didi signs a document calling on the world to address global climate change October, 2009 DROWNING IN RISING SEAS 2 ABSTRACT The threat of global climate change increasingly influences the actions of human society. As world leaders have negotiated adaptation strategies over the past couple of decades, a certain discourse has emerged that privileges Western conceptions of environmental degradation. I argue that this framing of climate change inhibits the successful implementation of adaptation strategies. This thesis focuses on a case study of the Maldives, an island nation deemed one of the most vulnerable locations to the impacts of rising sea levels. -

Indigenous-Hybrid Organisations in Colombia: a Multi-Level Analysis Within the Buen Vivir Model

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Indigenous-Hybrid Organisations in Colombia: A Multi-Level Analysis within the Buen Vivir Model Thesis How to cite: Morales Pachon, Andres (2019). Indigenous-Hybrid Organisations in Colombia: A Multi-Level Analysis within the Buen Vivir Model. PhD thesis The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2018 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21954/ou.ro.0000f316 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk INDIGENOUS-HYBRID ORGANISATIONS IN COLOMBIA: A MULTI-LEVEL ANALYSIS WITHIN THE BUEN VIVIR MODEL ANDRÉS MORALES A thesis submitted to the Open University in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The Open University Business School Department for Public Leadership and Social Enterprise November 2018 Acknowledgements I thank the following people for their support and immense contribution towards this study. First of all, I am grateful to Dr Michael Ngoasong, Professor Roger Spear and Dr Silvia Sacchetti for their input and guidance throughout the research process. It has been a privilege for me to be working under their distinguished, meticulous and persevering PhD supervision. I also thank Michael Murphy for his proofreading supervision and support. -

The Waves of Post-Development Theory and a Consideration of the Philippines

The Waves of Post-Development Theory and a Consideration of the Philippines Joseph Ahorro University of Alberta Introduction In the 1990s, post-development theorists argued against modernization and development for its reductionism, universalism, and ethnocentricity. Tracing the theoretical debates, I will identify two waves of post-development theory. While the first wave of post-development theory has been criticized for its rejection of development without qualification, there has been a second wave that responded and subsequently deepened the concept of post-development. Although there has been great strides to make post-development more inclusive and reflexive, the discipline has largely been rooted in experiences from Latin America, Africa, and India. What has been under-researched in the post-development literature is a consideration for countries in South East Asia. Acknowledging the diversity of culture, language, religion, heritage, and colonial experience, this paper will reflect on how the Philippine experience can make a contribution to post-development theory. In this paper, I will address three questions. First, what led to the second wave of post-development theory? Second, why consider post- development theory from a Philippine perspective? Third, what contributions can an analysis of a Philippine perspective offer towards the furthering of post-development theory? I will argue that categorizing post-development into two waves suggests that the theory has not stalled as a consequence of its initial shortfalls, but does in fact have room for growth as it will be demonstrated in the Philippine case. This paper will proceed in five steps. First, there will be a review of what I classify as the first wave of post-development theory. -

'Missionaries' in Bangladesh

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchArchive at Victoria University of Wellington Exploring the mission-development nexus through stories from Christian ‘missionaries’ in Bangladesh Anna Thompson 2012 A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Development Studies School of Geography, Environment and Earth Sciences Victoria University of Wellington Abstract Over the past decade, development research and policy has increasingly paid attention to religion and belief. Donors and researchers have progressively engaged with faith-based organisations and recipients. However, Christian mission and ‗missionaries‘ remain underexplored aspects within religion and development discourses. In response, this research explores stories from eleven Christian ‗missionaries‘ in Bangladesh. Firstly, I assess how the changing non-governmental sector in Bangladesh influenced participants‘ activities. Secondly, I contextualise their stories within religion and development discourses with reference to analyses of development workers. Finally, I reflect on the significance of spirituality in participants‘ lives. I also describe how spirituality played a role in my research. I frame this research within feminist and poststructuralist ways of knowing. Methodologically, I conducted semi-structured interviews and ‗hung out‘ with participants. I ‗wrote myself-in‘ to this research to highlight how the process intersected with my own subject positions. I found that participants‘ engaged with development in similar ways to development workers as analysed by others. They reproduced discourses of modernisation, expertise, altruism, and the ‗third world‘. They additionally responded to Christian discourses, such as ‗calling‘. Participants‘ activities and subjectivities were shaped by these intersecting discourses, and were also shaped by the historic and current setting of Bangladesh. -

Exploring Ecological Swaraj Or Radical Ecological Democracy : a Path Towards Postdevelopment in India

International Journal of Interdisciplinary and Multidisciplinary Studies (IJIMS), 2021, Vol 8, No.1,21-35. 21 Available online at http://www.ijims.com ISSN - (Print): 2519 – 7908 ; ISSN - (Electronic): 2348 – 0343 IF:4.335; Index Copernicus (IC) Value: 60.59; Peer-reviewed Journal Exploring Ecological Swaraj or Radical Ecological Democracy : A Path Towards Postdevelopment In India Akash Jash M.A. in Sociology, Jadavpur University, Kolkata, India Abstract The new phase of Postdevelopment theory is the phase of both deconstruction and reconstruction. Besides being a critique, it delves into the search for alternatives to development. Because of the claustrophobia of Development and recently neoliberalism and globalization, changes started to occur in almost all the axes of life (social, cultural, political, economic, ecological and scientific and spiritual). Many age-old concepts like Buen Vivir in Latin America, Ubuntu in Africa, Swaraj in India are getting envisioned in a new way through various social movements and alternative ways of living around the whole world, especially in the global South. Various 'Transition Discourses'(TD) are coming into existence which not only resist the arrogant intervention of development, but also resurface the other forms of life in this world. "A world of The third", non- capitalist in nature, is emerging which was hidden for so many years under the dominance of the Development Age. And these all are making the alternatives possible. A new experimental journey of postdevelopment is on its way to create a 'Pluriverse' - " a world where many worlds can be embraced". In the context of India, the purpose 'Development' serves is double. -

Pop / Rock / Commercial Music Wed, 25 Aug 2021 21:09:33 +0000 Page 1

Pop / Rock / Commercial music www.redmoonrecords.com Artist Title ID Format Label Print Catalog N° Condition Price Note 10000 MANIACS The wishing chair 19160 1xLP Elektra Warner GER 960428-1 EX/EX 10,00 € RE 10CC Look hear? 1413 1xLP Warner USA BSK3442 EX+/VG 7,75 € PRO 10CC Live and let live 6546 2xLP Mercury USA SRM28600 EX/EX 18,00 € GF-CC Phonogram 10CC Good morning judge 8602 1x7" Mercury IT 6008025 VG/VG 2,60 € \Don't squeeze me like… Phonogram 10CC Bloody tourists 8975 1xLP Polydor USA PD-1-6161 EX/EX 7,75 € GF 10CC The original soundtrack 30074 1xLP Mercury Back to EU 0600753129586 M-/M- 15,00 € RE GF 180g black 13 ENGINES A blur to me now 1291 1xCD SBK rec. Capitol USA 7777962072 USED 8,00 € Original sticker attached on the cover 13 ENGINES Perpetual motion 6079 1xCD Atlantic EMI CAN 075678256929 USED 8,00 € machine 1910 FRUITGUM Simon says 2486 1xLP Buddah Helidon YU 6.23167AF EX-/VG+ 10,00 € Verty little woc COMPANY 1910 FRUITGUM Simon says-The best of 3541 1xCD Buddha BMG USA 886972424422 12,90 € COMPANY 1910 Fruitgum co. 2 CELLOS Live at Arena Zagreb 23685 1xDVD Masterworks Sony EU 0888837454193 10,90 € 2 UNLIMITED Edge of heaven (5 vers.) 7995 1xCDs Byte rec. EU 5411585558049 USED 3,00 € 2 UNLIMITED Wanna get up (4 vers.) 12897 1xCDs Byte rec. EU 5411585558001 USED 3,00 € 2K ***K the millennium (3 7873 1xCDs Blast first Mute EU 5016027601460 USED 3,10 € Sample copy tracks) 2PLAY So confused (5 tracks) 15229 1xCDs Sony EU NMI 674801 2 4,00 € Incl."Turn me on" 360 GRADI Ba ba bye (4 tracks) 6151 1xCDs Universal IT 156 762-2 -

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 112 Peaches And Cream 411 Dumb 411 On My Knees 411 Teardrops 911 A Little Bit More 911 All I Want Is You 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 911 The Journey 10 cc Donna 10 cc I'm Mandy 10 cc I'm Not In Love 10 cc The Things We Do For Love 10 cc Wall St Shuffle 10 cc Dreadlock Holiday 10000 Maniacs These Are The Days 1910 Fruitgum Co Simon Says 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac & Elton John Ghetto Gospel 2 Unlimited No Limits 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Oh 3 feat Katy Perry Starstrukk 3 Oh 3 Feat Kesha My First Kiss 3 S L Take It Easy 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 38 Special Hold On Loosely 3t Anything 3t With Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds Of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds Of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds Of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Star Rain Or Shine Updated 08.04.2015 www.blazediscos.com - www.facebook.com/djdanblaze Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 50 Cent 21 Questions 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent Feat Neyo Baby By Me 50 Cent Featt Justin Timberlake & Timbaland Ayo Technology 5ive & Queen We Will Rock You 5th Dimension Aquarius Let The Sunshine 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up and Away 5th Dimension Wedding Bell Blues 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees I Do 98 Degrees The Hardest -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Versions Title Artist Versions #1 Crush Garbage SC 1999 Prince PI SC #Selfie Chainsmokers SS 2 Become 1 Spice Girls DK MM SC (Can't Stop) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue SF 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue MR (Don't Take Her) She's All I Tracy Byrd MM 2 Minutes To Midnight Iron Maiden SF Got 2 Stars Camp Rock DI (I Don't Know Why) But I Clarence Frogman Henry MM 2 Step DJ Unk PH Do 2000 Miles Pretenders, The ZO (I'll Never Be) Maria Sandra SF 21 Guns Green Day QH SF Magdalena 21 Questions (Feat. Nate 50 Cent SC (Take Me Home) Country Toots & The Maytals SC Dogg) Roads 21st Century Breakdown Green Day MR SF (This Ain't) No Thinkin' Trace Adkins MM Thing 21st Century Christmas Cliff Richard MR + 1 Martin Solveig SF 21st Century Girl Willow Smith SF '03 Bonnie & Clyde (Feat. Jay-Z SC 22 Lily Allen SF Beyonce) Taylor Swift MR SF ZP 1, 2 Step Ciara BH SC SF SI 23 (Feat. Miley Cyrus, Wiz Mike Will Made-It PH SP Khalifa And Juicy J) 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind SC 24 Hours At A Time Marshall Tucker Band SG 10 Million People Example SF 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney MM 10 Minutes Until The Utilities UT 24-7 Kevon Edmonds SC Karaoke Starts (5 Min 24K Magic Bruno Mars MR SF Track) 24's Richgirl & Bun B PH 10 Seconds Jazmine Sullivan PH 25 Miles Edwin Starr SC 10,000 Promises Backstreet Boys BS 25 Minutes To Go Johnny Cash SF 100 Percent Cowboy Jason Meadows PH 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago BS PI SC 100 Years Five For Fighting SC 26 Cents Wilkinsons, The MM SC SF 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris SC 26 Miles Four Preps, The SA 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters PI SC 29 Nights Danni Leigh SC 10000 Nights Alphabeat MR SF 29 Palms Robert Plant SC SF 10th Avenue Freeze Out Bruce Springsteen SG 3 Britney Spears CB MR PH 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan BS SC QH SF Len Barry DK 3 AM Matchbox 20 MM SC 1-2-3 Redlight 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

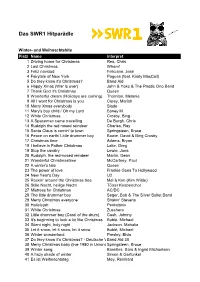

Das SWR1 Hitparädle

Das SWR1 Hitparädle Winter- und Weihnachtshits Platz Name Interpret 1 Driving home for Christmas Rea, Chris 2 Last Christmas Wham! 3 Feliz navidad Feliciano, José 4 Fairytale of New York Pogues (feat. Kirsty MacColl) 5 Do they know it's Christmas? Band Aid 6 Happy Xmas (War is over) John & Yoko & The Plastic Ono Band 7 Thank God it's Christmas Queen 8 Wonderful dream (Holidays are coming) Thornton, Melanie 9 All I want for Christmas is you Carey, Mariah 10 Merry Xmas everybody Slade 11 Mary's boy child / Oh my Lord Boney M. 12 White Christmas Crosby, Bing 13 A Spaceman came travelling De Burgh, Chris 14 Rudolph the red nosed reindeer Charles, Ray 15 Santa Claus is comin' to town Springsteen, Bruce 16 Peace on earth/ Little drummer boy Bowie, David & Bing Crosby 17 Christmas time Adams, Bryan 18 I believe in Father Christmas Lake, Greg 19 Stop the cavalry Lewie, Jona 20 Rudolph, the red-nosed reindeer Martin, Dean 21 Wonderful Christmastime McCartney, Paul 22 A winter's tale Queen 23 The power of love Frankie Goes To Hollywood 24 New Year's Day U2 25 Rockin' around the Christmas tree Mel & Kim (Kim Wilde) 26 Stille Nacht, heilige Nacht Tölzer Knabenchor 27 Mistress for Christmas AC/DC 28 The little drummer boy Seger, Bob & The Silver Bullet Band 29 Merry Christmas everyone Shakin' Stevens 30 Hallelujah Pentatonix 31 White Christmas Zucchero 32 Little drummer boy (Carol of the drum) Cash, Johnny 33 It's beginning to look a lot like Christmas Bublé, Michael 34 Silent night, holy night Jackson, Mahalia 35 Let it snow, let it snow, let it