The Importance of Continued Collecting of Bird Specimens to Ornithology and Bird Conservation J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Distribution, Natural History and Conservation Status of Two

Bird Conservation International (2008) 18:331–348. ª BirdLife International 2008 doi:10.1017/S0959270908007491 Printed in the United Kingdom Distribution, natural history and conservation status of two endemics of the Bolivian Yungas, Bolivian Recurvebill Simoxenops striatus and Yungas Antwren Myrmotherula grisea SEBASTIAN K. HERZOG, A. BENNETT HENNESSEY, MICHAEL KESSLER and VI´CTOR H. GARCI´A-SOLI´Z Summary Since their description in the first half of the 20th century by M. A. Carriker, Bolivian Recurvebill Simoxenops striatus and Yungas Antwren Myrmotherula grisea have been regarded as extremely poorly known endemics of the Bolivian Yungas and adjacent humid foothill forests. They are considered ‘Vulnerable’ under the IUCN criteria of small population, predicted population decline (criterion C2a) and, in the case of Bolivian Recurvebill, small extent of occurrence (criteria B1a+b). Here we summarise the information published to date and present extensive new data on the distribution (including the first records for extreme southeast Peru), natural history, population size and conservation status of both species based on field work in the Bolivian Andes over the past 12 years. Both species primarily inhabit the understorey of primary and mid-aged to older regenerating forest and regularly join mixed-species foraging flocks of insectivorous birds. Bolivian Recurvebill has a strong preference for Guadua bamboo, but it is not an obligate bamboo specialist and persists at often much lower densities in forests without Guadua. Yungas Antwren seems to have a preference for dense, structurally complex under- storey, often with Chusquea bamboo. Both species are distributed much more continuously at altitudes of mostly 600–1,500 m, occupy a greater variety of forest types (wet, humid, semi- deciduous forest) and have a much greater population size than previously thought. -

The Phylogenetic Position of Ambiortus: Comparison with Other Mesozoic Birds from Asia1 J

ISSN 00310301, Paleontological Journal, 2013, Vol. 47, No. 11, pp. 1270–1281. © Pleiades Publishing, Ltd., 2013. The Phylogenetic Position of Ambiortus: Comparison with Other Mesozoic Birds from Asia1 J. K. O’Connora and N. V. Zelenkovb aKey Laboratory of Evolution and Systematics, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, 142 Xizhimenwai Dajie, Beijing China 10044 bBorissiak Paleontological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, Profsoyuznaya ul. 123, Moscow, 117997 Russia email: [email protected], [email protected] Received August 6, 2012 Abstract—Since the last description of the ornithurine bird Ambiortus dementjevi from Mongolia, a wealth of Early Cretaceous birds have been discovered in China. Here we provide a detailed comparison of the anatomy of Ambiortus relative to other known Early Cretaceous ornithuromorphs from the Chinese Jehol Group and Xiagou Formation. We include new information on Ambiortus from a previously undescribed slab preserving part of the sternum. Ambiortus is superficially similar to Gansus yumenensis from the Aptian Xiagou Forma tion but shares more morphological features with Yixianornis grabaui (Ornithuromorpha: Songlingorni thidae) from the Jiufotang Formation of the Jehol Group. In general, the mosaic pattern of character distri bution among early ornithuromorph taxa does not reveal obvious relationships between taxa. Ambiortus was placed in a large phylogenetic analysis of Mesozoic birds, which confirms morphological observations and places Ambiortus in a polytomy with Yixianornis and Gansus. Keywords: Ornithuromorpha, Ambiortus, osteology, phylogeny, Early Cretaceous, Mongolia DOI: 10.1134/S0031030113110063 1 INTRODUCTION and articulated partial skeleton, preserving several cervi cal and thoracic vertebrae, and parts of the left thoracic Ambiortus dementjevi Kurochkin, 1982 was one of girdle and wing (specimen PIN, nos. -

Acoustic Monitoring of Night-Migrating Birds: a Progress Report

Acoustic Monitoring of Night-Migrating Birds: A Progress Report William R. Evans Kenneth V. Rosenberg Abstract—This paper discusses an emerging methodology that to give regular vocalizations in night migration are the vireos uses electronic technology to monitor vocalizations of night-migrat- (Vireonidae), flycatchers (Tyrannidae), and orioles (Icterinae). ing birds. On a good migration night in eastern North America, If a monitoring protocol is consistently maintained, an array thousands of call notes may be recorded from a single ground-based, of microphone stations can provide information on how the audio-recording station, and an array of recording stations across a species composition and number of vocal migrants vary across region may serve as a “recording net” to monitor a broad front of time and space. Such data have application for monitoring migration. Data from pilot studies in Florida, Texas, New York, and avian populations and identifying their migration routes. In British Columbia illustrate the potential of this technique to gather addition, detection and classification of distinctive call-types information that cannot be gathered by more conventional methods, is possible with computers (Mills 1995; Taylor 1995), thus such as mist-netting or diurnal counts. For example, the Texas information on bird populations might be gained automati- station detected a major migration of grassland sparrows, and a cally. In this paper, we summarize the current state of station in British Columbia detected hundreds of Swainson’s knowledge for identifying night-flight calls to species; present Thrushes; both phenomena were not detected with ground monitor- selected results from four ongoing studies that are monitoring ing efforts. -

Thinking with Birds: Mary Elizabeth Barber's Advocacy for Gender

Thinking with Birds: Mary Elizabeth Barber’s Advocacy for Gender Equality in Ornithology TANJA HAMMEL Department of History, University of Basel This article explores parts of the first South African woman ornithologist’s life and work. It concerns itself with the micro-politics of Mary Elizabeth Barber’s knowledge of birds from the 1860s to the mid-1880s. Her work provides insight into contemporary scientific practices, particularly the importance of cross-cultural collaboration. I foreground how she cultivated a feminist Darwinism in which birds served as corroborative evidence for female selection and how she negotiated gender equality in her ornithological work. She did so by constructing local birdlife as a space of gender equality. While male ornithologists naturalised and reinvigorated Victorian gender roles in their descriptions and depictions of birds, she debunked them and stressed the absence of gendered spheres in bird life. She emphasised the female and male birds’ collaboration and gender equality that she missed in Victorian matrimony, an institution she harshly criticised. Reading her work against the background of her life story shows how her personal experiences as wife and mother as well as her observation of settler society informed her view on birds, and vice versa. Through birds she presented alternative relationships to matrimony. Her protection of insectivorous birds was at the same time an attempt to stress the need for a New Woman, an aspect that has hitherto been overlooked in studies of the transnational anti-plumage -

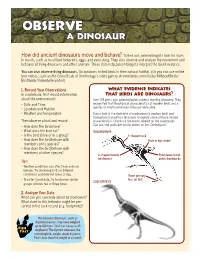

Observebserve a D Dinosaurinosaur

OOBSERVEBSERVE A DDINOSAURINOSAUR How did ancient dinosaurs move and behave? To fi nd out, paleontologists look for clues in fossils, such as fossilized footprints, eggs, and even dung. They also observe and analyze the movement and behavior of living dinosaurs and other animals. These data help paleontologists interpret the fossil evidence. You can also observe living dinosaurs. Go outdoors to fi nd birds in their natural habitat. (Or you can use online bird videos, such as the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s video gallery at www.birds.cornell.edu/AllAboutBirds/ BirdGuide/VideoGallery.html) 1. Record Your Observations What Evidence IndiCates In a notebook, fi rst record information That Birds Are Dinosaurs? about the environment: Over 125 years ago, paleontologists made a startling discovery. They • Date and Time recognized that the physical characteristics of modern birds and a • Location and Habitat species of small carnivorous dinosaur were alike. • Weather and temperature Take a look at the skeletons of roadrunner (a modern bird) and Coelophysis (an extinct dinosaur) to explore some of these shared Then observe a bird and record: characteristics. Check out the bones labeled on the roadrunner. • How does the bird move? Can you fi nd and label similar bones on the Coelophysis? • What does the bird eat? ROADRUNNER • Is the bird alone or in a group? S-shaped neck • How does the bird behave with Hole in hip socket members of its species? • How does the bird behave with members of other species? V-shaped furcula Pubis bone in hip (wishbone) points backwards Tips: • Weather conditions can affect how animals behave. -

TOUR REPORT Southwestern Amazonia 2017 Final

For the first time on a Birdquest tour, the Holy Grail from the Brazilian Amazon, Rondonia Bushbird – male (Eduardo Patrial) BRAZIL’S SOUTHWESTERN AMAZONIA 7 / 11 - 24 JUNE 2017 LEADER: EDUARDO PATRIAL What an impressive and rewarding tour it was this inaugural Brazil’s Southwestern Amazonia. Sixteen days of fine Amazonian birding, exploring some of the most fascinating forests and campina habitats in three different Brazilian states: Rondonia, Amazonas and Acre. We recorded over five hundred species (536) with the exquisite taste of specialties from the Rondonia and Inambari endemism centres, respectively east bank and west bank of Rio Madeira. At least eight Birdquest lifer birds were acquired on this tour: the rare Rondonia Bushbird; Brazilian endemics White-breasted Antbird, Manicore Warbling Antbird, Aripuana Antwren and Chico’s Tyrannulet; also Buff-cheeked Tody-Flycatcher, Acre Tody-Tyrant and the amazing Rufous Twistwing. Our itinerary definitely put together one of the finest selections of Amazonian avifauna, though for a next trip there are probably few adjustments to be done. The pre-tour extension campsite brings you to very basic camping conditions, with company of some mosquitoes and relentless heat, but certainly a remarkable site for birding, the Igarapé São João really provided an amazing experience. All other sites 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Brazil’s Southwestern Amazonia 2017 www.birdquest-tours.com visited on main tour provided considerably easy and very good birding. From the rich east part of Rondonia, the fascinating savannas and endless forests around Humaitá in Amazonas, and finally the impressive bamboo forest at Rio Branco in Acre, this tour focused the endemics from both sides of the medium Rio Madeira. -

The All-Bird Bulletin

Advancing Integrated Bird Conservation in North America Spring 2014 Inside this issue: The All-Bird Bulletin Protecting Habitat for 4 the Buff-breasted Sandpiper in Bolivia The Neotropical Migratory Bird Conservation Conserving the “Jewels 6 Act (NMBCA): Thirteen Years of Hemispheric in the Crown” for Neotropical Migrants Bird Conservation Guy Foulks, Program Coordinator, Division of Bird Habitat Conservation, U.S. Fish and Bird Conservation in 8 Wildlife Service (USFWS) Costa Rica’s Agricultural Matrix In 2000, responding to alarming declines in many Neotropical migratory bird popu- Uruguayan Rice Fields 10 lations due to habitat loss and degradation, Congress passed the Neotropical Migra- as Wintering Habitat for tory Bird Conservation Act (NMBCA). The legislation created a unique funding Neotropical Shorebirds source to foster the cooperative conservation needed to sustain these species through all stages of their life cycles, which occur throughout the Western Hemi- Conserving Antigua’s 12 sphere. Since its first year of appropriations in 2002, the NMBCA has become in- Most Critical Bird strumental to migratory bird conservation Habitat in the Americas. Neotropical Migratory 14 Bird Conservation in the The mission of the North American Bird Heart of South America Conservation Initiative is to ensure that populations and habitats of North Ameri- Aros/Yaqui River Habi- 16 ca's birds are protected, restored, and en- tat Conservation hanced through coordinated efforts at in- ternational, national, regional, and local Strategic Conservation 18 levels, guided by sound science and effec- in the Appalachians of tive management. The NMBCA’s mission Southern Quebec is to achieve just this for over 380 Neo- tropical migratory bird species by provid- ...and more! Cerulean Warbler, a Neotropical migrant, is a ing conservation support within and be- USFWS Bird of Conservation Concern and listed as yond North America—to Latin America Vulnerable on the International Union for Conser- Coordination and editorial vation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. -

Ultimate Bolivia Tour Report 2019

Titicaca Flightless Grebe. Swimming in what exactly? Not the reed-fringed azure lake, that’s for sure (Eustace Barnes) BOLIVIA 8 – 29 SEPTEMBER / 4 OCTOBER 2019 LEADER: EUSTACE BARNES Bolivia, indeed, THE land of parrots as no other, but Cotingas as well and an astonishing variety of those much-loved subfusc and generally elusive denizens of complex uneven surfaces. Over 700 on this tour now! 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Ultimate Bolivia 2019 www.birdquest-tours.com Blue-throated Macaws hoping we would clear off and leave them alone (Eustace Barnes) Hopefully, now we hear of colourful endemic macaws, raucous prolific birdlife and innumerable elusive endemic denizens of verdant bromeliad festooned cloud-forests, vast expanses of rainforest, endless marshlands and Chaco woodlands, each ringing to the chorus of a diverse endemic avifauna instead of bleak, freezing landscapes occupied by impoverished unhappy peasants. 2 BirdQuest Tour Report: Ultimate Bolivia 2019 www.birdquest-tours.com That is the flowery prose, but Bolivia IS that great destination. The tour is no longer a series of endless dusty journeys punctuated with miserable truck-stop hotels where you are presented with greasy deep-fried chicken and a sticky pile of glutinous rice every day. The roads are generally good, the hotels are either good or at least characterful (in a good way) and the food rather better than you might find in the UK. The latter perhaps not saying very much. Palkachupe Cotinga in the early morning light brooding young near Apolo (Eustace Barnes). That said, Bolivia has work to do too, as its association with that hapless loser, Che Guevara, corruption, dust and drug smuggling still leaves the country struggling to sell itself. -

Groenkloof A3 Brochure

PO Box 1454, Pretoria, 0001 Pretoria, 1454, Box PO . y c i l o p e d i r - o n , t e m l e h - o n a e v a h e w t a h t e t o n e s a e l P . a e r a c i n c i p e h t e t i s o p p o Groenkloof Nature Reserve Nature Groenkloof Address: e e s o p r u p s i h t r o f y t u d n o s i l a i c i f f o n a s y a d i l o h c i l b u p n o d n a s d n e k e e w r e v O . k e e w e h t g n i r u d e c i f f o s ’ e v r e s e R e h t t a d e r i h e b n a c s t e m l e h d n a s e k i b n i a t n u o M .za [email protected] E-mail: mountain bikers just to have a fun day out enjoying nature and viewing game. viewing and nature enjoying out day fun a have to just bikers mountain Fax: 086 516 3449 516 086 Fax: and is a great and safe trail for professionals to do their training and for social social for and training their do to professionals for trail safe and great a is and el: (012) 440 8316 440 (012) el: T f Boshof David Management: The ± 20 km mountain bike trail consist of an adventurous single and jeep track track jeep and single adventurous an of consist trail bike mountain km 20 ± The TRAIL BIKE AIN MOUNT .za [email protected] E-mail: Fax: 086 512 9536 512 086 Fax: el: (012) 440 8316 440 (012) el: T Bookings: s are fed. -

Prevalence of Chlamydia Psittaci in Domesticated and Fancy Birds in Different Regions of District Faisalabad, Pakistan

United Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Research Article Prevalence of Chlamydia Psittaci in Domesticated and Fancy Birds in Different Regions of District Faisalabad, Pakistan Siraj I1, Rahman SU1, Ahsan Naveed1* Anjum Fr1, Hassan S2, Zahid Ali Tahir3 1Institute of Microbiology, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad 2Institute of Animal Nutrition and Feed Technology, University of Agriculture Faisalabad, Pakistan 3DiagnosticLaboraoty, Kamalia, Toba Tek Singh, Pakistan Volume 1 Issue 1- 2018 1. Abstract Received Date: 15 July 2018 1.1. Introduction Accepted Date: 31 Aug 2018 The study was aimed to check the prevalence of this zoonotic bacterium which is a great risk Published Date: 06 Sep 2018 towards human population in district Faisalabad at Pakistan. 1.2. Methodology 2. Key words Chlamydia Psittaci; Psittacosis; In present study, a total number of 259 samples including fecal swabs (187) and blood samples Prevalence; Zoonosis (72) from different aviculture of 259 birds such as chickens, ducks, pigeons, parrots, Australian parrots, and peacock were collected from different regions of Faisalabad, Pakistan. After process- ing the samples were inoculated in the yolk sac of embryonated chicken eggs for the cultivation ofChlamydia psittaci(C. psittaci)and later identified through Modified Gimenez staining and later CFT was performed for the determination of antibodies titer against C. psittaci. 1.3. Results The results of egg inoculation and modified Gimenez staining showed 9.75%, 29.62%, 10%, 36%, 44.64% and 39.28% prevalence in the fecal samples of chickens, ducks, peacocks, parrots, pi- geons and Australian parrots respectively. Accordingly, the results of CFT showed 15.38%, 25%, 46.42%, 36.36% and 25% in chickens, ducks, pigeons, parrots and peacock respectively. -

ZOOLOGY Exploring the Biodiversity of Colorado and Theworld

CHAPTER 4 — ZOOLOGY Exploring the Biodiversity of Colorado and the World CHAPTER 4 ZOOLOGY Exploring the Biodiversity of Colorado and the World Jeffrey T. Stephenson, Before the Museum Paula E. Cushing, The first collections of specimens that make up what is now the Denver John R. Demboski, and Museum of Nature & Science were actually established well before the Frank-T. Krell founding of the institution in 1900, the selection of a board of trustees, or the construction of a building to house and exhibit the specimens. Edwin Carter (1830–1900) (Fig. 4.1) collected Colorado birds and mammals from the 1860s through the 1890s. Born in New York in 1830, Carter arrived in Colorado in 1859 hoping to make it rich in the goldfields, but he soon became interested in the region’s natural history. He learned hide tanning and, as his prospects for hitting the mother lode faded, he earned his living selling buckskin clothing that he handcrafted. Carter supplemented these earnings by mar- keting foodstuffs and other provisions to the growing population of successful and (mostly) unsuccessful prospectors flooding the region. His interest in nature turned to concern as he observed dwindling numbers of mammals and birds, owing largely to habitat destruction and overhunting. Period photographs of the area’s mining district show a landscape largely denuded of vegetation. By the 1870s, Carter noted that many animal species were becoming scarce. The state’s forests were being devastated, ranches and farms were replacing open prairie, and some species, including the last native bison in Colorado, were on the verge of extirpation or extinction. -

Alaska Legal Pet Guide Possession Import Take Comments

ALASKA LEGAL PET GUIDE POSSESSION IMPORT TAKE COMMENTS This is only a guide of animals that MAY be legal in a state. Due to the extensive amount of laws involved that are constantly changing, UAPPEAL and contributors of these guides cannot guarantee the accuracy of the information. Users are responsible for checking all laws BEFORE getting an animal. Legal as Pets as Legal Permit Register Pets for Legal Permit Pets for Legal ARACHNID, CENTIPEDE, MILLIPEDE All Yes No No Yes No Yes No known ADFG laws BATS Myotis, Keen's No No No Native/Live Game - Banned as pets Myotis, Little Brown No No No Native/Live Game - Banned as pets Silver-haired No No No Native/Live Game - Banned as pets All No No NA Live game - banned as pets BEARS Black No No No Native/Live Game - Banned as pets Brown No No No Native/Live Game - Banned as pets Polar No No No Native/Live Game - Banned as pets All No No NA Live game - no pets BIRDS Albatross, Black-footed No No No Native/Live Game - Banned as pets Albatross, Short-tailed No No No State Endangered; Native species - banned as pets Ammoperdix (Genus) Yes Yes No Yes Yes NA Aviculture Permit needed to import or possess Canary Yes No No Yes NA Exempt Live Game - No ADFG permit needed; See Ag laws Capercaille Yes Yes No Yes Yes NA Aviculture Permit needed to import or possess Chickadee, Black-capped No No No Native/Live Game - Banned as pets Chickadee, Boreal No No No Native/Live Game - Banned as pets Chickadee, Chestnut-backed No No No Native/Live Game - Banned as pets Chickadee, Gray-headed No No No Native/Live Game