Connecting Managers, Service Providers and Clients in Bombali District, Sierra Leone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

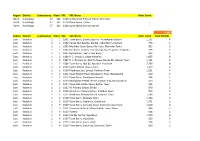

Region District Constituency Ward VRC VRC Name Voter Count North

Region District Constituency Ward VRC VRC Name Voter Count North Koinadugu 47 162 6169 Al-Harrakan Primary School, Woredala - North Koinadugu 47 162 6179 Open Space 2,Kabo - North Koinadugu 47 162 6180 Open Space, Kamayortortor - 9,493 Region District Constituency Ward VRC VRC Name Voter Count Total PS(100) East Kailahun 1 1 1001 Town Barry, Baoma, Baoma - Kunywahun Section 1,192 4 East Kailahun 1 1 1002 Palava Hut, Baoma, Baoma - Gborgborma Section 478 2 East Kailahun 1 1 1003 Mofindor Court Barry, Mofindor, Mofindor Town 835 3 East Kailahun 1 1 1004 Methodist primary school yengema, Yengama, Yengema 629 2 East Kailahun 1 1 1005 Nyanyahun Town, Town Barry 449 2 East Kailahun 1 2 1006 R. C. School 1, Upper Masanta 1,855 6 East Kailahun 1 2 1007 R. C. Primary 11, Gbomo Town, Buedu RD, Gbomo Town 1,121 4 East Kailahun 1 2 1008 Town Barry, Ngitibu, Ngitibu 1-Kailahum 2,209 8 East Kailahun 1 2 1009 KLDEC School, new London 1,259 4 East Kailahun 1 2 1010 Methodist Sec. School, Kailahun Town 1,031 4 East Kailahun 1 2 1011 Town Market Place, Bandajuma Town, Bandajuma 640 2 East Kailahun 1 2 1012 Town Barry, Bandajuma Sinneh 294 1 East Kailahun 1 2 1013 Bandajuma Health Centre, Luawa Foiya, Bandajuma Si 473 2 East Kailahun 1 2 1014 Town Hall, Borbu-Town, Borbu- Town 315 1 East Kailahun 1 2 1015 RC Primary School, Borbu 870 3 East Kailahun 1 2 1016 Amadiyya Primary School, Kailahun Town 973 3 East Kailahun 1 2 1017 Methodist Primary School, kailahun Town 1,266 4 East Kailahun 1 3 1018 Town Barry, Sandialu Town 1,260 4 East Kailahun 1 3 1019 Town -

IOM Sierra Leone Situation Report 22-28 February 2015, Issue 13

IOM Sierra Leone Ebola Response SITUATION REPORT | Issue 13 | 22-28 February 2015 © IOM 2015 © OFDA 2015 © IOM 2015 Dr Desmond Maada Kangba of IOM’s Training Academy in Freetown stresses correct Infection Prevention and Control procedures during the second Emergency Simulation Exercise held at Lungi Airport on 23 February. SITUATION OVERVIEW HIGHLIGHTS The steep decline in case incidence nationally in Sierra IOM’s National Ebola Training Academy has now trained over 4,000 Leone from December until the end of January has halt- health care workers as of 28 February. A week long mobile training ed. Weekly case incidence has stabilized at between 60 course is ongoing in Bombali district for two teams of 27 and 100 confirmed cases. A total of 63 cases were report- decontamination workers. ed in the week to 22 February. The total for the previous week has been revised up to 96 confirmed cases, after IOM’s Health and Humanitarian Border Management team missing laboratory data was included. Transmission re- successfully concluded a second Emergency Simulation Exercise on mains widespread, with 8 districts reporting new con- 23 February. The team will now lead a rapid two day border firmed cases. A significant proportion of cases are still arising from unknown chains of transmission. assessment to Kambia district on 2-3 March involving a number of There has been a sharp increase in reported confirmed government and UN agencies. Four additional rapid assessment cases in the northern district of Bombali, with 20 con- missions will be held during March. firmed cases reported in the week to 22 February. -

Download Map (PDF | 2.83

Banko Botoko 13°30'WKola Tarihoy Sébouri 12°W Cisséla 10°30'W Sodioré Porédaka Dalaba Dabola Sankiniana Madiné Saraya Diata KAMBIA AREA Moussaya Dando Diaguissa Kébéya BOFFA Sangaréya Kokou Banko PITA 2- 22 APRIL 2015 KoDnionudooliu Forécariah Forécariah DALABA Nafaya Bonko Douma Timbo FORECARIAH Alemaniya Kukuna Sokolon Kambia TELIMELE DABOLA Bérika N Yenguissa ' Doufa 0 Léfuré 3 Kondoya ° FRIA 0 Kébalé 1 FORECARIAH Toumanya Aria Fria Bramaya Sembakounian Haroumaia KAMBIA Farmoréya Nemina Basia Konkouré Koba Koundéyagbé Sangoya Yérémbeli Yenguissa KAMBIA Kimbo Katiya N Dabolatounka ' Sabendé Mooria Sormoréa 0 UNMEER 3 Tondon ° Sangodiya Konta 0 Mamou G U I N E A PORT Tawa 1 Diguila Yékéiakidé ACCESSIBILITY MAP MAMOU Bantagnellé LOKToOumania Toromélun Domiya Kounsouta Tanéné Moléya Kambia May 2015 Sérékoroba Yenyéya Bobiya Dialaman Séguéya Gbafaré Daragbé Barmoi Madiha ^! National Capital Road Network Passaya P Nounkou Donsikira Boketto Kondébounba Mansiramoribaya Administrative Capital Highway Moribaia Kanbian Portofita Boto ! Boavalkourou Town/Village Main Road 2 April 2015 10h35 track Sansanko , Baki Konia Koumbaya DUBREKA Bambaya ¾H ETC FalissSadeécondary Road Bambafouga 2 April 2015 11h01 Rokupr MCHPCCC track GObousnskoumyaaria Sougéta BirissKaychom Kassiri KINDIA Koumandi Féfélabaya Bayagui Kalia 3 April 2015 9h32 Gbalathalan MCHP and Kawula CHP CCC track Mambolo Kirita Koura Koubiya Kaba Bontala Konta Soubétidé Based on available data as at Samaya Kolenté 5 April 2015 8h59 Kakun Bramia CCC track Kondéboun Romeni W5as sMouay 2015. -

G U I N E a Liberia Sierra Leone

The boundaries and names shown and the designations Mamou used on this map do not imply official endorsement or er acceptance by the United Nations. Nig K o L le n o G UINEA t l e a SIERRA Kindia LEONEFaranah Médina Dula Falaba Tabili ba o s a g Dubréka K n ie c o r M Musaia Gberia a c S Fotombu Coyah Bafodia t a e r G Kabala Banian Konta Fandié Kamakwie Koinadugu Bendugu Forécariah li Kukuna Kamalu Fadugu Se Bagbe r Madina e Bambaya g Jct. i ies NORTHERN N arc Sc Kurubonla e Karina tl it Mateboi Alikalia L Yombiro Kambia M Pendembu Bumbuna Batkanu a Bendugu b Rokupr o l e Binkolo M Mange Gbinti e Kortimaw Is. Kayima l Mambolo Makeni i Bendou Bodou Port Loko Magburaka Tefeya Yomadu Lunsar Koidu-Sefadu li Masingbi Koundou e a Lungi Pepel S n Int'l Airport or a Matotoka Yengema R el p ok m Freetown a Njaiama Ferry Masiaka Mile 91 P Njaiama- Wellington a Yele Sewafe Tongo Gandorhun o Hastings Yonibana Tungie M Koindu WESTERN Songo Bradford EAS T E R N AREA Waterloo Mongeri York Rotifunk Falla Bomi Kailahun Buedu a i Panguma Moyamba a Taiama Manowa Giehun Bauya T Boajibu Njala Dambara Pendembu Yawri Bendu Banana Is. Bay Mano Lago Bo Segbwema Daru Shenge Sembehun SOUTHE R N Gerihun Plantain Is. Sieromco Mokanje Kenema Tikonko Bumpe a Blama Gbangbatok Sew Tokpombu ro Kpetewoma o Sh Koribundu M erb Nitti ro River a o i Turtle Is. o M h Sumbuya a Sherbro I. -

Download PDF File

AMOUN TOTAL EMIS CHIEFD LOCATIO SCHOOL ENROL COUNCIL WARD SCHOOL NAME T PER AMOUNT CODE OM N LEVEL MENT CHILD PAID WATERL 45 85 5103-3-09029 WARDC OO 391 WILLIAM ABDUL JALIL ACADEMY PRE-PRIMARY SCHOOL PRE-PRIMARY 10,000 850,000 RURAL STREET KONO DISTRICT TANKOR East DOWN ABDULAI IBN ABASS PRE-SCHOOL PRE PRIMARY 110 1391-1-01995 1,100,000 O BALOP ABERDEE 106 5208-2-10849 FREETOWN CITY COUNCIL ABERDEEN MUNICIPAL PRE-PRIMARY 1,060,000 N KONO DISTRICT NIMIKOR East KOMAO AFRICA COMMUNITY EMPOERMENT DEVELOPMENT PRE PRIMARY 151 1309-1-02125 1,510,000 O KONO DISTRICT GBENSE East YARDU AFRICA COMMUNITY EMPOERMENT DEVELOPMENT PRE PRIMARY 127 1391-1-01802 1,270,000 ROAD MAGBEM 102 3105-1-02506 KAMBIA DISTRICT 201 ROBAT AHMADIYYA MUSLIM PRE PRIMARY SCHOOL-ROBAT PRE-PRIMARY 1,020,000 A 60 2401-1-05230 DANSOGO BUMBUNA PRE-PRIMARY 600,000 TONKOLILI DISTRICT 185 AHMADIYYA MUSLIM PRE-PRIMARY SCHOOL 54 2417-1-05764 YELE YELE PRE-PRIMARY 540,000 TONKOLILI DISTRICT 176 AHMADIYYA MUSLIM PRE-PRIMARY SCHOOL TIKONK 150 311301112 BO DISTRICT 289 KAKUA AHMADIYYA MUSLIM PRE-SCHOOL 10,000.00 1,500,000 O PRE-PRIMARY KHOLIFA MAGBURA 83 2407-1-05340 TONKOLILI DISTRICT ROWALL 170 AHMADIYYA MUSLIM PRE-SCHOOL PRE-PRIMARY 830,000 KA A KUNIKE- 105 2410-1-05521 TONKOLILI DISTRICT 179 MASINGBI AHMADIYYA PRE-SCHOOL PRE-PRIMARY 1,050,000 SANDA MAKENI ROGBOM/ 83 2191-1-04484 BOMBALI DISTRICT 123 ALHADI ISLAMIC NURSERY SCHOOL PRE-PRIMARY 830,000 CITY MAKENI 151 319101126 BO CITY KAKUA BO NO 2 ALHAJI NAZI-ALIE PRE-SCHOOL PRE-PRIMARY 1,510,000 TIMBO/M 80 2191-1-04505 BOMBALI DISTRICT -

Sierra Leone Unamsil

13o 30' 13o 00' 12o 30' 12o 00' 11o 30' 11o 00' 10o 30' Mamou The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply ger GUINEA official endorsemenNt ior acceptance by the UNAMSIL K L United Nations. o l o e l n a Deployment as of t e AugustKindia 2005 Faranah o o 10 00' Médina 10 00' National capital Dula Provincial capital Tabili s a Falaba ie ab o c K g Dubréka Town, village r n a o c M S Musaia International boundary t Gberia Coyah a Bafodia UNMO TS-11 e Provincial boundary r Fotombu G Kabala Banian Konta Bendugu 9o 30' Fandié Kamakwie Koinadugu 9o 30' Forécariah Kamalu li Kukuna Fadugu Se s ie agbe c B Madina r r a e c SIERRA LEONE g Jct. e S i tl N Bambaya Lit Ribia Karina Alikalia Kurubonla Mateboi HQ UNAMSIL Kambia M Pendembu Yombiro ab Batkanuo Bendugu l e Bumbuna o UNMO TS-1 o UNMO9 00' HQ Rokupr a 9 00' UNMO TS-4 n Mamuka a NIGERIA 19 Gbinti p Binkolo m Kayima KortimawNIGERIA Is. 19 Mange a Mambolo Makeni P RUSSIA Port Baibunda Loko JORDAN Magburaka Bendou Mape Lungi Tefeya UNMO TS-2 Bodou Lol Rogberi Yomadu UNMO TS-5 Lunsar Matotoka Rokel Bridge Masingbi Koundou Lungi Koidu-Sefadu Pepel Yengema li Njaiama- e Freetown M o 8o 30' Masiaka Sewafe Njaiama 8 30' Goderich Wellington a Yonibana Mile 91 Tungie o Magbuntuso Makite Yele Gandorhun M Koindu Hastings Songo Buedu WESTERN Waterloo Mongeri Falla York Bradford UNMO TS-9 AREA Tongo Giehun Kailahun Tolobo ia Boajibu Rotifunk a T GHANA 11 Taiama Panguma Manowa Banana Is. -

Local Council Ward Boundary Delimitation Report

April 2008 NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION Sierra Leone Local Council Ward Boundary Delimitation Report Volume One February 2008 This page is intentionally left blank TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword 1 Executive Summary 3 Introduction 5 Stages in the Ward Boundary Delimitation Process 7 Stage One: Establishment of methodology including drafting of regulations 7 Stage Two: Allocation of Local Councils seats to localities 13 Stage Three: Drawing of Boundaries 15 Stage Four: Sensitization of Stakeholders and General Public 16 Stage Five: Implement Ward Boundaries 17 Conclusion 18 APPENDICES A. Database for delimiting wards for the 2008 Local Council Elections 20 B. Methodology for delimiting ward boundaries using GIS technology 21 B1. Brief Explanation of Projection Methodology 22 C. Highest remainder allocation formula for apportioning seats to localities for the Local Council Elections 23 D. List of Tables Allocation of 475 Seats to 19 Local Councils using the highest remainder method 24 25% Population Deviation Range 26 Ward Numbering format 27 Summary Information on Wards 28 E. Local Council Ward Delimitation Maps showing: 81 (i) Wards and Population i (ii) Wards, Chiefdoms and sections EASTERN REGION 1. Kailahun District Council 81 2. Kenema City Council 83 3. Kenema District Council 85 4. Koidu/New Sembehun City Council 87 5. Kono District Council 89 NORTHERN REGION 6. Makeni City Council 91 7. Bombali District Council 93 8. Kambia District Council 95 9. Koinadugu District Council 97 10. Port Loko District Council 99 11. Tonkolili District Council 101 SOUTHERN REGION 12. Bo City Council 103 13. Bo District Council 105 14. Bonthe Municipal Council 107 15. -

District Summary Bombali

DISTRICT SUMMARY FixingFIXING HEALTH Health POSTS PostsBOMBALITO SAVE toLIVES Save LivesADVANCING PARTNERS & COMMUNITIES, SIERRA LEONE STRENGTHENING REPRODUCTIVE, MATERNAL, NEWBORN, AND CHILD HEALTH SERVICES AS PART OF THE POST-EBOLA TRANSITION JUNE 2017 INTRODUCTION Bombali District’s 111 primary health facilities serve an (284 on government payroll, 255 volunteers). Of these, 78 estimated 606,544 people (Statistics Sierra Leone and are state-enrolled community health nurses (SECHN); 335 Government of Sierra Leone, 2016). The primary health are maternal and child health aides (MCH aides); 16 are facilities include 9 maternal and child health posts (MCHP); community health officers (CHOs); 1 a state-registered 71 community health posts (CHPs); 20 community health nurse (SRN); 87 are regular trained nurses; 8 are community centers (CHCs); and 11 private clinics (faith-based and health assistants (CHA); and 14 are midwives (Ministry of others) (Sierra Leone Ministry of Health and Sanitation, Health and Sanitation, Sierra Leone, Directorate of Human WHO, Service Availability and Readiness Assessment [SARA], Resources for Health). 2017). The services are provided by 539 health care workers Table 1. Volume of Selected Health Services Provided in Bombali, 2016 DELIVERIES ANC4 FULLY IMMUNIZED* MALARIA DIARRHEA CASES TOTAL FP U5 TREATED OPD TREATED PHU COMMUNITY PHU OUT-REACH PHU OUTREACH AT THE PHU WITH ACT 14,838 288 10,049 4,226 12,002 6,556 58,915 139,390 12,012 318,226 * Indicates child has received bacillus Calmette-Guérine, oral poliovirus, all 3 doses of pneumococcal conjugate, pentavalent, rotavirus, measles, and yellow fever vaccines according to schedule. ACT: artemisinin-based combination therapy. ANC4: antenatal care 4th visit. -

Kailahun District Constituencies And

NEC: Report on Electoral Constituency Boundaries Delimitation Process Process Delimitation Boundaries Constituency Electoral on Report NEC: 4.1.1 KAILAHUN DISTRICT CONSTITUENCIES AND POPULATION Eastern Region Constituency Maps 1103 a 43,427 m i a g g n K n e i o s T s T i i i s Penguia s K is is Yawei K K Luawa 1101 e 49,499 r 1104 1108 g n 33,457 54,363 o B Kpeje je e Upper West p K Bambara 1102 44,439 1107 Chiefdom Boundary 37,484 Constituency Code Njaluahun Mandu – 1101 Constituency 1 August 2006 August Dea 1102 Constituency 2 Jawie 1103 Constituency 3 1106 Malema 1104 Constituency 4 42,639 1105 Constituency 5 1105 1106 Constituency 6 52,882 1107 Constituency 7 1108 Constituency 8 42,639 Constituency Population PREPARED BY STATISTICS SIERRA LEONE KENEMA DISTRICT CONSTITUENCIES AND POPULATION Gorama Mende 1207 49,953 Wandor 1206 48,429 n u h Simbaru o g Lower le 1208 Dodo Bambara a M 54,312 1205 42,184 Kandu Leppiama 1204 51,486 1202 1201 42,262 Nongowa 43,308 # Small Bo # Kenema # 1203 1209 Town 42,832 44,045 Dama 1210 Niawa 36341 Gaura Langrama Koya 1211 Nomo 42,796 Chiefdom Boundary Constituency Code Tunkia 1201 Constituency 1 1202 Constituency 2 1203 Constituency 3 1204 Constituency 4 1205 Constituency 5 1206 Constituency 6 1207 Constituency 7 1208 Constituency 8 1209 Constituency 9 1210 Constituency 10 1211 Constituency 11 42,796 Constituency Population PREPARED BY STATISTICS SIERRA LEONE NEC: Report on Electoral Constituency Boundaries Delimitation Process – August 2006 NEC: Report on Electoral Constituency Boundaries Delimitation -

9. Ibemenuga and Avoaja

Animal Research International (2014) 11(1): 1905 – 1916 1905 ASSESSMENT OF GROUNDWATER QUALITY IN WELLS WITHIN THE BOMBALI DISTRICT, SIERRA LEONE 1IBEMENUGA, Keziah Nwamaka and 2AVOAJA, Diana Akudo 1Department of Biological Sciences, Fourah Bay College, University of Sierra Leone, Mount Aureol, Freetown, Sierra Leone. 2Department of Zoology and Environmental Biology, Michael Okpara University, Umudike, Abia State, Nigeria. Corresponding Author: Ibemenuga, K. N. Department of Biological Sciences, Anambra State University, Uli, Anambra State, Nigeria. Email: [email protected] Phone: +234 8126421299 ABSTRACT This study assessed the quality of 60 groundwater wells within the Bombali District of Sierra Leone. Water samples from the wells were analysed for physical (temperature, turbidity, conductivity, total dissolved solids and salinity), chemical (pH, nitrate-nitrogen, sulphate, calcium, ammonia, fluoride, aluminium, iron, copper and manganese) parameters using potable water testing kit; and bacteriological (faecal and non-faecal coliforms) qualities. Results show that 73% of the samples had turbidity values below the WHO, ICMR and United USPHS standards of 5 NTU. The electrical conductivity (µµµS/cm) of 5% of the whole samples exceeded the WHO guideline value, 8% of the entire samples had values higher than the WHO, ICMR and USPHS recommended concentration. In terms of iron, 25% of all the samples had values in excess of WHO, ICMR and USPHS recommended value of 0.3mg/l. For manganese, 12% of the entire samples had values more than the WHO and ICMR standards. On the other hand, more water samples (22%) had manganese values above USPHS guideline value. For bacteriological quality, 28% of the wells were polluted by faecal and non-faecal coliforms. -

Continuous Results Monitoring and Support System

Continuous Results Monitoring and Support System Bombali/Sierra Leone First Bimonthly Report September 2016 Continuous Results Monitoring and Support System Report—SIAPS/Sierra Leone, September 2016 This report is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the US Agency for International Development (USAID), under the terms of cooperative agreement number AID-OAA-A-11-00021. The contents are the responsibility of Management Sciences for Health and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. About SIAPS The goal of the Systems for Improved Access to Pharmaceuticals and Services (SIAPS) Program is to ensure the availability of quality pharmaceutical products and effective pharmaceutical services to achieve desired health outcomes. Toward this end, the SIAPS results areas include improving governance, building capacity for pharmaceutical management and services, addressing information needed for decision-making in the pharmaceutical sector, strengthening financing strategies and mechanisms to improve access to medicines, and increasing quality pharmaceutical services. Recommended Citation This report may be reproduced if credit is given to SIAPS. Please use the following citation. Continuous Results Monitoring and Support System Report Bombali/ Sierra Leone, September 2016. Submitted to the US Agency for International Development by the Systems for Improved Access to Pharmaceuticals and Services (SIAPS) Program. Arlington, VA: Management Sciences for Health. Key Words Sierra Leone, Bombali, Continuous Results Monitoring and Support System (CRMS) Report Systems for Improved Access to Pharmaceuticals and Services Pharmaceuticals and Health Technologies Group Management Sciences for Health 4301 North Fairfax Drive, Suite 400 Arlington, VA 22203 USA Telephone: 703.524.6575 Fax: 703.524.7898 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.siapsprogram.org ii CONTENTS Acronyms ...................................................................................................................................... -

Sierra Leone

GOVERNMENT OF SIERRA LEONE Survey of Availability of Modern Contraceptives and Essential Life-Saving Maternal and Reproductive Health Medicines in Service Delivery Points in Sierra Leone VOLUME TWO - TABLES Z2p(1 − p) n = d2 Where n = minimal sample size for each domain Z = Z score that corresponds to a confidence interval p = the proportion of the attribute (type of SDP) expressed in decimal d = percent confidence level in decimal February 2011 UNFPA SIERRA LEONE Because everyone counts This is Volume Two of the results of the Survey on the Availability of ModernContraceptives and Essential Life-Saving Maternal and Reproductive Health Medicines in Service Delivery Points in Sierra Leone. It is published by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Country Office in Sierra Leone. It contains all tables generated from collected data, while Volume One (published separately) presents the Analytical Report. Both are intended to fill the critical dearth of reliable, high quality and timely data for programme monitoring and evaluation. Cover Diagram: Use of sampling formula to obtain sample size in Volume One UNFPA SIERRA LEONE Survey of Availability of Modern Contraceptives and Essential Life-Saving Maternal and Reproductive Health Medicines in Service Delivery Points in Sierra Leone VOLUME TWO - TABLES Survey of Availability of Modern Contraceptives and Essential Life-Saving Maternal and Reproductive Health Medicines in Service Delivery Points in Sierra Leone: VOLUME TWO - TABLES 3 UNFPA SIERRA LEONE 4 Survey of Availability of Modern Contraceptives