Late Iron Age Calleva…

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research News Issue 15

NEWSLETTER OF THE ENGLISH HERITAGE RESEARCH DEPARTMENT Inside this issue... RESEARCH Introduction ...............................2 NEW DISCOVERIES AND INTERPRETATIONS NEWS Photo finish for England’s highest racecourse ...................3 Aldborough in focus: air photographic analysis and © English Heritage mapping of the Roman town of Isurium Brigantium ...........6 Recent work at Marden Henge, Wiltshire .................... 10 Manningham: an historic area assessment of a Bradford suburb .................... 14 DEVELOPING METHODOLOGIES English Heritage Coastal Estate Risk Assessment ....... 18 UNDERSTANDING PLACES Understanding place ............ 20 Celebrating People & Place: guidance on commemorative plaques .................................... 22 NOTES & NEWS ................. 23 RESEARCH DEPARTMENT REPORTS LIST ....................... 27 3D lidar model showing possible racecourse on Alston Common, Cumbria – see story page 3 NEW PUBLICATIONS ......... 28 NUMBER 15 AUTUMN 2010 ISSN 1750-2446 This issue of Research News is published soon after the Government’s Comprehensive Spending Review (CSR) announcement, which for English Heritage means a cut of 32% to our grant in aid over the next four years from 1st April 2011. On a more positive note the Government sees a continuing role for English Heritage and values the independent expert advice it provides. Research Department staff make an important contribution to the organisation’s expertise. Applied research will continue to be an important part of the role of English Heritage and from April 2011 it will be integrated with our designation, planning and advice functions as part of the National Heritage Protection Plan (NHPP). The Plan, published on our website on the 7th December 2010, will focus our research effort and other activities on those heritage assets that are both significant and under threat. In response to the CSR and the NHPP Research News will, from 2011, be published twice rather than three times a year, and focus on reporting on the range of research activities contributing to the Plan. -

Fishbourne: a Roman Palace and Its Garden, 1971, Barry W. Cunliffe, 0801812666, 9780801812668, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1971

Fishbourne: A Roman Palace and Its Garden, 1971, Barry W. Cunliffe, 0801812666, 9780801812668, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1971 DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1O80BJ2 http://goo.gl/Rblvo http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fishbourne_A_Roman_Palace_and_Its_Garden DOWNLOAD http://goo.gl/R4Dxp http://bit.ly/W9p35D The Roman Villa in Britain , Albert Lionel Frederick Rivet, 1969, Pavements, Mosaic, 299 pages. Excavations at Fishbourne, 1961-1969, Issue 26, Volume 1 , Barry W. Cunliffe, 1971, History, 221 pages. Facing the Ocean The Atlantic and Its Peoples, 8000 BC-AD 1500, Barry W. Cunliffe, Jan 1, 2001, History, 600 pages. An illustrated history of the peoples of "the Atlantic rim" explores the inter- relatedness of European cultures that stretched from Iceland to Gibralter.. The Romans at Ribchester discovery and excavation, B. J. N. Edwards, University of Lancaster. Centre for North-West Regional Studies, Jan 1, 2000, History, 101 pages. Germania , Cornelius Tacitus, 1970, History, 175 pages. Offers a portrait of Julius Agricola - the governor of Roman Britain and Tacitus' father-in-law - and an account of Britain that has come down to us. This book provides. The Recent Discoveries of Roman Remains Found in Repairing the North Wall of the City of Chester (A Series of Papers Read Before the Chester Archaeological and Historic Society, Etc., and Reprinted by Permission of the Council.) Extensively Illustrated, John Parsons Earwaker, 1888, Romans, 175 pages. Roman Canterbury, as so far revealed by the work of the Canterbury Excavation Committee , Canterbury Excavation Committee, 1949, History, 16 pages. Roman Silchester the archaeology of a Romano-British town, George C. Boon, 1957, Silchester (England), 245 pages. -

Download the KAFS Booking Form for All of Our Forthcoming Courses Directly from Our Website, Or by Clicking Here

WELCOME TO THE JANUARY NEWSETTER EDITORIAL FROM KAFS MUST SEE STUDY DAYS We will be sending a Newsletter email each month to keep you up to date FIELD TRIPS with news and views on what is planned at the Kent Archaeological Field School and what is happening on the larger stage of archaeology both in BREAKING NEWS this country and abroad. Talking of which we are extremely lucky this year to READING AT THE MOMENT be able to dig with the University of Texas at Oplontis just next door to Pompeii. We have just three places left so hurry with that booking! SHORT STORY COURSES KAFS BOOKING FORM At home we are digging the last of three Bronze Age round barrows at Hollingbourne in Kent where last year in Barrow 2 we found a crouched burial and a complete bovine burial (below). Work will continue on two Roman villa estates, one at Abbey Farm in Faversham, the other at Teston located above the River Medway close to Maidstone. Work will continue on two Roman villa estates, one at Abbey Farm in Faversham, the other at Teston located above the River Medway close to Maidstone. So, look at our web site at www.kafs.co.uk in 2014 for details of courses and ‘behind the scenes’ trips with KAFS. We hear all the time in the press about threats to our woodland and heritage and Rescue has over many years brought our attention to the ‘creeping threat’ of development on our historic wellbeing. Dr Chris Cumberpatch has written this letter to the Times which we need to take notice of: Sir, After your report and letters (Jan 2) it is time to stand back and look at what we may be allowing to be done to this country in the name of development and its presumed role as the solution to our economic woes. -

RULES of PLAY COIN Series, Volume VIII by Marc Gouyon-Rety

The Fall of Roman Britain RULES OF PLAY COIN Series, Volume VIII by Marc Gouyon-Rety T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S 1.0 Introduction ............................2 6.0 Epoch Rounds .........................18 2.0 Sequence of Play ........................6 7.0 Victory ...............................20 3.0 Commands .............................7 8.0 Non-Players ...........................21 4.0 Feats .................................14 Key Terms Index ...........................35 5.0 Events ................................17 Setup and Scenarios.. 37 © 2017 GMT Games LLC • P.O. Box 1308, Hanford, CA 93232 • www.GMTGames.com 2 Pendragon ~ Rules of Play • 58 Stronghold “castles” (10 red [Forts], 15 light blue [Towns], 15 medium blue [Hillforts], 6 green [Scotti Settlements], 12 black [Saxon Settlements]) (1.4) • Eight Faction round cylinders (2 red, 2 blue, 2 green, 2 black; 1.8, 2.2) • 12 pawns (1 red, 1 blue, 6 white, 4 gray; 1.9, 3.1.1) 1.0 Introduction • A sheet of markers • Four Faction player aid foldouts (3.0. 4.0, 7.0) Pendragon is a board game about the fall of the Roman Diocese • Two Epoch and Battles sheets (2.0, 3.6, 6.0) of Britain, from the first large-scale raids of Irish, Pict, and Saxon raiders to the establishment of successor kingdoms, both • A Non-Player Guidelines Summary and Battle Tactics sheet Celtic and Germanic. It adapts GMT Games’ “COIN Series” (8.1-.4, 8.4.2) game system about asymmetrical conflicts to depict the political, • A Non-Player Event Instructions foldout (8.2.1) military, religious, and economic affairs of 5th Century Britain. -

Cunetio Roman Town, Mildenhall Marlborough, Wiltshire

Wessex Archaeology Cunetio Roman Town, Mildenhall Marlborough, Wiltshire Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Ref: 71509 July 2011 CUNETIO ROMAN TOWN, MILDENHALL, MARLBOROUGH, WILTSHIRE Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Prepared for: Videotext Communications Ltd 11 St Andrew’s Crescent CARDIFF CF10 3DB by Wessex Archaeology Portway House Old Sarum Park SALISBURY Wiltshire SP4 6EB Report reference: 71509.01 Path: \\Projectserver\WESSEX\PROJECTS\71509\Post Ex\Report\71509/TT Cunetio Report (ed LNM) July 2011 © Wessex Archaeology Limited 2011 all rights reserved Wessex Archaeology Limited is a Registered Charity No. 287786 Cunetio Roman Town, Mildenhall, Marlborough, Wiltshire Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results DISCLAIMER THE MATERIAL CONTAINED IN THIS REPORT WAS DESIGNED AS AN INTEGRAL PART OF A REPORT TO AN INDIVIDUAL CLIENT AND WAS PREPARED SOLELY FOR THE BENEFIT OF THAT CLIENT. THE MATERIAL CONTAINED IN THIS REPORT DOES NOT NECESSARILY STAND ON ITS OWN AND IS NOT INTENDED TO NOR SHOULD IT BE RELIED UPON BY ANY THIRD PARTY. TO THE FULLEST EXTENT PERMITTED BY LAW WESSEX ARCHAEOLOGY WILL NOT BE LIABLE BY REASON OF BREACH OF CONTRACT NEGLIGENCE OR OTHERWISE FOR ANY LOSS OR DAMAGE (WHETHER DIRECT INDIRECT OR CONSEQUENTIAL) OCCASIONED TO ANY PERSON ACTING OR OMITTING TO ACT OR REFRAINING FROM ACTING IN RELIANCE UPON THE MATERIAL CONTAINED IN THIS REPORT ARISING FROM OR CONNECTED WITH ANY ERROR OR OMISSION IN THE MATERIAL CONTAINED IN THE REPORT. LOSS OR DAMAGE AS REFERRED TO ABOVE SHALL BE DEEMED TO INCLUDE, BUT IS NOT LIMITED TO, ANY LOSS OF PROFITS OR ANTICIPATED PROFITS DAMAGE TO REPUTATION OR GOODWILL LOSS OF BUSINESS OR ANTICIPATED BUSINESS DAMAGES COSTS EXPENSES INCURRED OR PAYABLE TO ANY THIRD PARTY (IN ALL CASES WHETHER DIRECT INDIRECT OR CONSEQUENTIAL) OR ANY OTHER DIRECT INDIRECT OR CONSEQUENTIAL LOSS OR DAMAGE QUALITY ASSURANCE SITE CODE 71509 ACCESSION CODE CLIENT CODE PLANNING APPLICATION REF. -

ARTHUR of CAMELOT and ATHTHE-DOMAROS of CAMULODUNUM: a STRATIGRAPHY-BASED EQUATION PROVIDING a NEW CHRONOLOGY for 1St MIILLENNIUM ENGLAND

1 Gunnar Heinsohn (15 June 2017) ARTHUR OF CAMELOT AND ATHTHE-DOMAROS OF CAMULODUNUM: A STRATIGRAPHY-BASED EQUATION PROVIDING A NEW CHRONOLOGY FOR 1st MIILLENNIUM ENGLAND “It seems probable that Camelot, Chrétien de Troyes’ [c. 1140-1190 AD] name for Arthur's Court, is derived directly from Camelod-unum, the name of Roman Colchester. The East Coast town was probably well-known to this French poet, though whether he knew of any specific associations with Arthur is unclear. […] John Morris [1973] suggests that Camulodunum might actually have been the High-King Arthur's Eastern Capital” (David Nash Ford 2000). "I think we can dispose of him [Arthur] quite briefly. He owes his place in our history books to a 'no smoke without fire' school of thought. [...] The fact of the matter is that there is no historical evidence about Arthur; we must reject him from our histories and, above all, from the titles of our books" (David N. Dumville 1977, 187 f.) I Why neither the habitats of Arthurian Celts nor the cities of their Saxon foes can be found in post-Roman Britain p. 2 II Contemporaneity of Saxons, Celts and Romans during the conquest of Britain in the Late Latène period of Aththe[Aθθe]-Domaros of Camulodunum/Colchester p. 14 III Summary p. 29 IV Bibliography p. 30 Author’s1 address p. 32 1 Thanks for editorial assistance go to Clark WHELTON (New York). 2 I Why neither the habitats of Arthurian Celts nor the cities of their Saxon foes can be found in post-Roman Britain “There is absolutely no justification for believing there to have been a historical figure of the fifth or sixth century named Arthur who is the basis for all later legends. -

Ii. Sites in Britain

II. SITES IN BRITAIN Adel, 147 Brough-by-Bainbridge, 32 Alcester, cat. #459 Brough-on-Noe (Navia), cat. #246, Aldborough, 20 n.36 317, 540 Antonine Wall, 20 n.36, 21, 71, 160, 161 Brough-under-Stainmore, 195 Auchendavy, I 61, cat. #46, 225, 283, Burgh-by-Sands (Aballava), 100 n.4, 301, 370 118, 164 n.32, cat. #215, 216, 315, 565-568 Backworth, 61 n.252, 148 Burgh Castle, 164 n.32 Bakewell, cat. #605 Balmuildy, cat. #85, 284 Cadder, cat. #371 Bar Hill, cat. #296, 369, 467 Caerhun, 42 Barkway, 36, 165, cat. #372, 473, 603 Caerleon (lsca), 20 n.36, 30, 31, 51 Bath (Aquae Sulis), 20, 50, 54 n.210, n.199, 61 n.253, 67, 68, 86, 123, 99, 142, 143, 147, 149, 150, 151, 128, 129, 164 n.34, 166 n.40, 192, 157 n.81, 161, 166-171, 188, 192, 196, cat. #24, 60, 61, 93, 113, I 14, 201, 206, 213, cat. #38, 106, 470, 297, 319, 327, 393, 417 526-533 Caernarvon (Segontium), 42 n.15 7, Benwell (Condercum), 20 n.36, 39, 78, 87-88, 96 n.175, 180, 205, 42 n.157, 61, 101, 111-112, 113, cat. #229 121, 107 n.41, 153, 166 n.40, 206, Caerwent (Venta Silurum), 143, 154, cat. #36, 102, 237, 266, 267, 318, 198 n. 72, cat. #469, 61 7 404, 536, 537, 644, 645 Canterbury, 181, 198 n.72 Bertha, cat. #5 7 Cappuck, cat. #221 Bewcastle (Fan um Cocidi), 39, 61, I 08, Carley Hill Quarry, 162 111 n.48, 112, 117, 121, 162, 206, Carlisle (Luguvalium), 43, 46, 96, 112, cat. -

Pounds Text Make-Up

A HISTORY OF THE ENGLISH PARISH f v N. J. G. POUNDS The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge , UK http: //www.cup.cam.ac.uk West th Street, New York –, USA http://www.cup.org Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne , Australia © N. J. G. Pounds This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeset in Fournier MT /.pt in QuarkXPress™ [] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress cataloguing in publication data Pounds, Norman John Greville. A history of the English parish: the culture of religion from Augustine to Victoria / N. J. G. Pounds. p. cm. Includes index. . Parishes – England – History. Christianity and culture – England – History. England – Church history. Title. Ј.Ј – dc – hardback f v CONTENTS List of illustrations page viii Preface xiii List of abbreviations xv Church and parish Rectors and vicars: from Gratian to the Reformation The parish, its bounds and its division The urban parish The parish and its servants The economics of the parish The parish and the community The parish and the church courts: a mirror of society The parish church, popular culture and the Reformation The parish: its church and churchyard The fabric of the church: the priest’s church The people’s church: the nave and the laity Notes Index vii f v ILLUSTRATIONS The traditional English counties xxvi . -

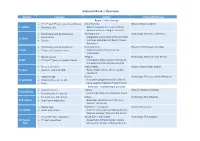

Suburani Book 1 Overview

Suburani Book 1 Overview Chapter Language Culture History/Mythology Roma – life in the city • 1st, 2nd and 3rd pers. sg., present tense Life in the city History: Rome in AD 64 1: Subūrai • Reading Latin Subura; Population of city of Rome; Women at work; Living in an insula • Nominative and accusative sg. Building Rome Mythology: Romulus and Remus • Declensions Geography and growth of Rome; Public 2: Rōma • Gender buildings and spaces of Rome; Forum Romanum • Nominative and accusative pl. Entertainment History: Three phases of ruling 3: lūdī • 3rd pers. pl., present tense Public festivals; Chariot-racing; Charioteers • Neuter nouns Religion Mythology: Deucalion and Pyrrha 4: deī • 1st and 2nd pers. pl., present tense Christianity; State religion; Homes of the gods; Sacrifice; Private worship • Present infinitive Public health History: Rome under attack! 5: aqua • possum, volō and nōlō Baths; Public toilets; Water supply; Sanitation • Ablative case Slavery Mythology: Theseus and the Minotaur 6: servitium • Prepositions + acc./+ abl. How were people enslaved? Life of a • Time slave; Seeking freedom; Manumission Britannia – establishing a province • Imperfect tense London History: Romans invading 7: Londīnium • Perfect tense (-v- stems) Londinium; Made in Londinium; Food • Perfect tense (all stems) Britain Mythology: The Amazons 8: Britannia • Superlative adjectives Britannia; Camulodunum; Resist or accept? The Druids • Dative case Rebellion – hard power History: Resistance 9: rebelliō • Verbs with dative Chain of command; Competing forces; Women and war; Why join the army? • 1st and 2nd decl. adjectives Aquae Sulis – soft power Mythology: The Gorgons 10: Aquae • 3rd decl. adjectives Aquae Sulis; Different gods; Curses; Sūlis Military life; People of Roman Britain Gaul and Lusitania – life in a province • Genitive case The sea History: Pirates in the Mediterranean Sea • -ne and -que Romans and the sea; Underwater 11: mare archaeology; Navigation and maps; Dangers at sea • Imperatives (inc. -

The Battle of Watling Street Took Place in Roman-Occupied Britain in AD 60 Or

THE BATTLE OF WATLING STREET Margaret McGoverne First published in Great Britain in 2017 by Bright Shine Press Brightshinepress.com Copyright © Margaret McGoverne 2017 The right of Margaret McGoverne to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 All rights reserved. No parts of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. For my boy, remembering our drives along the Icknield Way Contents Map of Roman Britain Principal Characters Place Names in Roman Britain Acknowledgements Background Part I Part II Part III Part IV Part V Epilogue Extract from The Bondage of The Soil Map of Roman Britain Principal Characters Dedo A young attendant of Queen Boudicca Boudicca Queen of the Iceni tribe, widow of King Prasutagus Brigomall A noble of the Iceni tribe, advisor to the queen Cata A young maiden in Boudicca’s travelling bodyguard Dias An elder of the village of Puddlehill Nemeta Younger daughter of Boudicca and Prasutagus Prasutagus King of the Iceni tribe, lately deceased Vassinus A young serving lad and friend of Dedo Mallo A mule owned by Dedo Place Names in Roman Britain Albion England Cambria Wales Camulodunum Colchester Durocobrivis Dunstable Hibernia Ireland Lactodurum Towcester Londinium London Magiovinium Fenny Stratford Venta Caistor St Edmund, Suffolk Icenorum Verlamion The Catuvellauni capital Verulamium Saint Albans (formerly Verlamion) Viroconium Wroxeter Cornoviorum Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to a number of people, although this list is by no means exhaustive. -

Roman Roads of Britain

Roman Roads of Britain A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Thu, 04 Jul 2013 02:32:02 UTC Contents Articles Roman roads in Britain 1 Ackling Dyke 9 Akeman Street 10 Cade's Road 11 Dere Street 13 Devil's Causeway 17 Ermin Street 20 Ermine Street 21 Fen Causeway 23 Fosse Way 24 Icknield Street 27 King Street (Roman road) 33 Military Way (Hadrian's Wall) 36 Peddars Way 37 Portway 39 Pye Road 40 Stane Street (Chichester) 41 Stane Street (Colchester) 46 Stanegate 48 Watling Street 51 Via Devana 56 Wade's Causeway 57 References Article Sources and Contributors 59 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 61 Article Licenses License 63 Roman roads in Britain 1 Roman roads in Britain Roman roads, together with Roman aqueducts and the vast standing Roman army, constituted the three most impressive features of the Roman Empire. In Britain, as in their other provinces, the Romans constructed a comprehensive network of paved trunk roads (i.e. surfaced highways) during their nearly four centuries of occupation (43 - 410 AD). This article focuses on the ca. 2,000 mi (3,200 km) of Roman roads in Britain shown on the Ordnance Survey's Map of Roman Britain.[1] This contains the most accurate and up-to-date layout of certain and probable routes that is readily available to the general public. The pre-Roman Britons used mostly unpaved trackways for their communications, including very ancient ones running along elevated ridges of hills, such as the South Downs Way, now a public long-distance footpath. -

Roman Britain | Small Group Tour for Seniors | Odyssey Traveller

Australia 1300 888 225 New Zealand 0800 440 055 [email protected] From $11,995 AUD Single Room $14,195 AUD Twin Room $11,995 AUD Prices valid until 30th December 2021 22 days Duration England Destination Level 2 - Moderate Activity Roman Britain Aug 05 2022 to Aug 26 2022 Explore Roman Britain with Odyssey Traveller Join Odyssey Traveller on this small group tour as we explore the world of Roman Britain, tracing the visible remains of Roman occupation in England and Wales. The Romans occupied Britain for some 400 years and left behind a lasting legacy. While many buildings were pulled down and reused there is still a lot left for us to discover. Join us as we travel in the footsteps of the Roman legions, exploring what remains of their cities, fortresses, villas, bath houses and roads. Roman Britain 06-Oct-2021 1/13 https://www.odysseytraveller.com.au Australia 1300 888 225 New Zealand 0800 440 055 [email protected] Small group tours Roman Britain itinerary This tour begins in London, where we will travel back in time to explore Londinium, roman London, the settlement established on the current site of the city around the year 43. With a private guide we take a walking tour around the London Wall, a defensive wall built by Romans that defined the city’s boundaries until the Late Middle Ages. Though the wall was demolished in the 17th century, the ruins can still be traced through private and public properties. Our London city tour also includes a visit to the remains of an ancient temple devoted to the mystery god Mithras, and a trip to the Museum of London, which houses relics of the original temple.