897 the Emergence of a Normative Principle of Co-Operative Federalism and Its Application I. Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Four Courts of Sir Lyman Duff

THE FOUR COURTS OF SIR LYMAN DUFF RICHARD GOSSE* Vancouver I. Introduction. Sir Lyman Poore Duff is the dominating figure in the Supreme Court of Canada's first hundred years. He sat on the court for more than one-third of those years, in the middle period, from 1906 to 1944, participating in nearly 2,000 judgments-and throughout that tenure he was commonly regarded as the court's most able judge. Appointed at forty-one, Duff has been the youngest person ever to have been elevated to the court. Twice his appointment was extended by special Acts of Parliament beyond the mandatory retirement age of seventy-five, a recogni- tion never accorded to any other Canadian judge. From 1933, he sat as Chief Justice, having twice previously-in 1918 and 1924 - almost succeeded to that post, although on those occasions he was not the senior judge. During World War 1, when Borden considered resigning over the conscription issue and recommending to the Governor General that an impartial national figure be called upon to form a government, the person foremost in his mind was Duff, although Sir Lyman had never been elected to public office. After Borden had found that he had the support to continue himself, Duff was invited to join the Cabinet but declined. Mackenzie King con- sidered recommending Duff for appointment as the first Canadian Governor General. Duff undertook several inquiries of national interest for the federal government, of particular significance being the 1931-32 Royal Commission on Transportation, of which he was chairman, and the 1942 investigation into the sending of Canadian troops to Hong Kong, in which he was the sole commissioner . -

Constitutionalism and the Genetic Non-Discrimination Act Reference Shannon Hale* and Dwight Newman, QC**

31 Constitutionalism and the Genetic Non-Discrimination Act Reference Shannon Hale* and Dwight Newman, QC** I. Introduction In the July 10, 2020 decision in Reference re Genetic Non-Discrimination Act (GNDA Reference),1 the Supreme Court of Canada arrived at a complex three-to-two-to-four outcome, with a slim five-justice majority in two separate judgments upholding challenged portions of the fed- eral Genetic Non-Discrimination Act (GNDA)2 as a valid exercise of Parliament’s criminal law power. The legislation, which some thought fundamentally oriented to the goal of preventing genetic discrimination, seemed to have attractive policy objectives, though we will ultimately suggest that the form of the legislation was not entirely in keeping with these aims. While it may have appeared pragmatically attractive to uphold the legislation, we suggest that the majority’s decision to do so comes at great cost to basic federalism principles, to legal predict- ability, and to prospects for well-informed intergovernmental cooperation. We argue that the courts must properly confine the effects of the GNDA Reference in accordance with established principles on the treatment of fragmented judicial opinions. We also argue that the courts must take significant steps to ensure that federalism jurisprudence remains well-grounded in legal principle, without the actual or apparent influence of extra-legal policy considerations. * BA, MSc, JD, Member of the Ontario bar. Research Associate, University of Saskatchewan College of Law (September 2020 to December 2020 term). ** BA, JD, BCL, MPhil, DPhil, Member of the Ontario and Saskatchewan bars. Professor of Law & Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Rights in Constitutional and International Law, University of Saskatchewan College of Law. -

Canadian Law Library Review Revue Canadienne Des Bibliothèques Is Published By: De Droit Est Publiée Par

CANADIAN LAW LIBRARY REVIEW REVUE CANADIENNE DES BIBLIOTHÈQUES DE DROIT 2017 CanLIIDocs 227 VOLUME/TOME 42 (2017) No. 2 APA Journals® Give Your Users the Psychological Research They Need LEADING JOURNALS IN LAW AND PSYCHOLOGY 2017 CanLIIDocs 227 Law and Human Behavior® Official Journal of APA Division 41 (American Psychology-Law Society) Bimonthly • ISSN 0147-7307 2.884 5-Year Impact Factor®* | 2.542 2015 Impact Factor®* Psychological Assessment® Monthly • ISSN 1040-3590 3.806 5-Year Impact Factor®* | 2.901 2015 Impact Factor®* Psychology, Public Policy, and Law® Quarterly • ISSN 1076-8971 2.612 5-Year Impact Factor®* | 1.986 2015 Impact Factor®* Journal of Threat Assessment and Management® Official Journal of the Association of Threat Assessment Professionals, the Association of European Threat Assessment Professionals, the Canadian Association of Threat Assessment Professionals, and the Asia Pacific Association of Threat Assessment Professionals Quarterly • ISSN 2169-4842 * ©Thomson Reuters, Journal Citation Reports® for 2015 ENHANCE YOUR PSYCHOLOGY SERIALS COLLECTION To Order Journal Subscriptions, Contact Your Preferred Subscription Agent American Psychological Association | 750 First Street, NE | Washington, DC 20002-4242 USA ‖‖ CONTENTS / SOMMAIRE 5 From the Editor The Law of Declaratory Judgments 40 De la rédactrice Reviewed by Melanie R. Bueckert 7 President’s Message Pocket Ontario OH&S Guide to Violence and 41 Le mot de la présidente Harassment Reviewed by Megan Siu 9 Featured Articles Articles de fond Power of Persuasion: Essays -

Canadian Law Library Review Revue Canadienne Des Bibliothèques Is Published By: De Droit Est Publiée Par

CANADIAN LAW LIBRARY REVIEW REVUE CANADIENNE DES BIBLIOTHÈQUES DE DROIT VOLUME/TOME 42 (2017) No. 2 APA Journals® Give Your Users the Psychological Research They Need LEADING JOURNALS IN LAW AND PSYCHOLOGY Law and Human Behavior® Official Journal of APA Division 41 (American Psychology-Law Society) Bimonthly • ISSN 0147-7307 2.884 5-Year Impact Factor®* | 2.542 2015 Impact Factor®* Psychological Assessment® Monthly • ISSN 1040-3590 3.806 5-Year Impact Factor®* | 2.901 2015 Impact Factor®* Psychology, Public Policy, and Law® Quarterly • ISSN 1076-8971 2.612 5-Year Impact Factor®* | 1.986 2015 Impact Factor®* Journal of Threat Assessment and Management® Official Journal of the Association of Threat Assessment Professionals, the Association of European Threat Assessment Professionals, the Canadian Association of Threat Assessment Professionals, and the Asia Pacific Association of Threat Assessment Professionals Quarterly • ISSN 2169-4842 * ©Thomson Reuters, Journal Citation Reports® for 2015 ENHANCE YOUR PSYCHOLOGY SERIALS COLLECTION To Order Journal Subscriptions, Contact Your Preferred Subscription Agent American Psychological Association | 750 First Street, NE | Washington, DC 20002-4242 USA ‖‖ CONTENTS / SOMMAIRE 5 From the Editor The Law of Declaratory Judgments 40 De la rédactrice Reviewed by Melanie R. Bueckert 7 President’s Message Pocket Ontario OH&S Guide to Violence and 41 Le mot de la présidente Harassment Reviewed by Megan Siu 9 Featured Articles Articles de fond Power of Persuasion: Essays by a Very Public 41 Edited by John -

1050 the ANNUAL REGISTER Or the Immediate Vicinity. Hon. E. M. W

1050 THE ANNUAL REGISTER or the immediate vicinity. Hon. E. M. W. McDougall, a Puisne Judge of the Superior Court for the Province of Quebec: to be Puisne Judge of the Court of King's Bench in and for the Province of Quebec, with residence at Montreal or the immediate vicinity. Pierre Emdle Cote, K.C., New Carlisle, Que.: to be a Puisne Judge of the Superior Court in and for the Province of Quebec, effective Oct. 1942, with residence at Quebec or the immediate vicinity. Dec. 15, Henry Irving Bird, Vancouver, B.C.: to be a Puisne Judge of the Supreme Court of British Columbia, with residence at Vancouver, or the immediate vicinity. Frederick H. Barlow, Toronto, Ont., Master of the Supreme Court of Ontario: to be a Judge of the High Court of Justice for Ontario. Roy L. Kellock, K.C., Toronto, Ont.: to be a Justice of the Court of Appeal for Ontario and ex officio a Judge of the High Court of Juscico for Ontario. 1943. Feb. 4, Robert E. Laidlaw, K.C., Toronto, Ont.: to be a Justice of the Court of Appeal for Ontario and ex officio a Judge of the High Court of Justice for Ontario. Apr. 22, Hon. Thane Alexander Campbell, K.C., Summer- side, P.E.I.: to be Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Judicature of P.E.I. Ivan Cleveland Rand, K.C., Moncton, N.B.: to be a Puisne Judge of the Supreme Court of Canada. July 5, Hon. Justice Harold Bruce Robertson, a Judge of the Supreme Court of British Columbia: to be a Justice of Appeal of the Court of Appeal for British Columbia. -

A Decade of Adjustment 1950-1962

8 A Decade of Adjustment 1950-1962 When the newly paramount Supreme Court of Canada met for the first timeearlyin 1950,nothing marked theoccasionasspecial. ltwastypicalof much of the institution's history and reflective of its continuing subsidiary status that the event would be allowed to pass without formal recogni- tion. Chief Justice Rinfret had hoped to draw public attention to the Court'snew position throughanotherformalopeningofthebuilding, ora reception, or a dinner. But the government claimed that it could find no funds to cover the expenses; after discussing the matter, the cabinet decided not to ask Parliament for the money because it might give rise to a controversial debate over the Court. Justice Kerwin reported, 'They [the cabinet ministers] decided that they could not ask fora vote in Parliament in theestimates tocoversuchexpensesas they wereafraid that that would give rise to many difficulties, and possibly some unpleasantness." The considerable attention paid to the Supreme Court over the previous few years and the changes in its structure had opened broader debate on aspects of the Court than the federal government was willing to tolerate. The government accordingly avoided making the Court a subject of special attention, even on theimportant occasion of itsindependence. As a result, the Court reverted to a less prominent position in Ottawa, and the status quo ante was confirmed. But the desire to avoid debate about the Court discouraged the possibility of change (and potentially of improvement). The St Laurent and Diefenbaker appointments during the first decade A Decade of Adjustment 197 following termination of appeals showed no apparent recognition of the Court’s new status. -

A Challenging Wine Trade, Part 2 Chris Wilson

A challenging wine trade, part 2 Chris Wilson 1 External and internal trade challenges B.C., Ontario, Quebec, Nova WTO Challenges Scotia and Federal measures Comeau The Hicken Report (Interprovincial trade) 3 General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade Article III:1 (internal taxes) 1. The contracting parties recognize that internal taxes and other internal charges, and laws, regulations and requirements affecting the internal sale, offering for sale, purchase, transportation, distribution or use of products, and internal quantitative regulations requiring the mixture, processing or use of products in specified amounts or proportions, should not be applied to imported or domestic products so as to afford protection to domestic production. 3 4 General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade Article III:4 (national treatment) The products of the territory of any contracting party imported into the territory of any other contracting party shall be accorded treatment no less favourable than that accorded to like products of national origin in respect of all laws, regulations and requirement affecting their internal sale, offering for sale, purchase, transportation, distribution or use. 4 5 General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade Article XVII:1 (state trading enterprises) Each contracting party undertakes that if it establishes or maintains a State enterprise, wherever located, or grants to any enterprise, formally or in effect, exclusive or special privileges,* such enterprise shall, in its purchases or sales involving either imports or exports, act in a manner consistent with the general principles of non-discriminatory treatment prescribed in this Agreement for governmental measures affecting imports or exports by private traders. 5 6 General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade Article XXIV:12 (regional governments) Each contracting party shall take such reasonable measures as may be available to it to ensure observance of the provisions of this Agreement by the regional and local governments and authorities within its territories. -

Download Download

THE SUPREME COURT’S STRANGE BREW: HISTORY, FEDERALISM AND ANTI-ORIGINALISM IN COMEAU Kerri A. Froc and Michael Marin* Introduction Canadian beer enthusiasts and originalists make unlikely fellow travellers. However, both groups eagerly awaited and were disappointed by the Supreme Court of Canada’s decision in R v Comeau.1 The case came to court after Gerard Comeau was stopped and charged by the RCMP in a “sting” operation aimed at New Brunswickers bringing cheaper alcohol from Quebec across the provincial border to be enjoyed at home.2 Eschewing Gerard Comeau’s plea to “Free the Beer”, the Court upheld as constitutional provisions in New Brunswick’s Liquor Control Act, which made it an offence to possess liquor in excess of the permitted amount not purchased from the New Brunswick Liquor Corporation.3 The Court’s ruling was based on section 121 of the Constitution Act, 1867, which states that “[a]ll articles of Growth, Produce, or Manufacture of any one of the Provinces…be admitted free into each of the other Provinces.”4 In the Court’s view, this meant only that provinces could not impose tariffs on goods from another province. It did not apply to non-tariff barriers, like New Brunswick’s monopoly on liquor sales in favour of its Crown corporation. In so deciding, the Court upheld the interpretation set out in a nearly 100-year-old precedent, Gold Seal Ltd v Attorney- General for the Province of Alberta,5 albeit amending its interpretation of section 121 to prohibit both tariffs and “tariff-like” barriers. The Supreme Court also criticized the trial judge’s failure to respect stare decisis in overturning this precedent. -

225 Watertight Compartments: Getting Back to the Constitutional Division of Powers I. Introduction

GETTING BACK TO THE CONSTITUTIONAL DIVISION OF POWERS 225 WATERTIGHT COMPARTMENTS: GETTING BACK TO THE CONSTITUTIONAL DIVISION OF POWERS ASHER HONICKMAN* This article offers a fresh examination of the constitutional division of powers. The author argues that sections 91 and 92 of the Constitution Act, 1867 establish exclusive jurisdictional spheres — what the Privy Council once termed “watertight compartments.” This mutual exclusivity is emphasized and reinforced throughout these sections and leaves very little room for legitimate overlap. While some degree of overlap is permissible under this scheme — particularly incidental effects, genuine double aspects, and limited ancillary powers — overlap must be constrained in a principled fashion to comply with the exclusivity principle. The modern trend toward flexibility and freer overlap is contrary to the constitutional text. The author argues that while some deviation from the text is inevitable due to the presumption of constitutionality and stare decisis, the Supreme Court should return to a more exclusivist footing in accordance with the text. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................. 226 II. THE EXCLUSIVITY PRINCIPLE .................................. 227 A. FROM QUEBEC TO THE BRITISH PARLIAMENT ................. 227 B. THE NON OBSTANTE CLAUSE AND THE DEEMING PROVISION ...... 231 C. CONCURRENT POWERS ................................... 234 III. PITH AND SUBSTANCE AND LEGITIMATE OVERLAP ................. 235 A. INTERJURISDICTIONAL IMMUNITY ......................... -

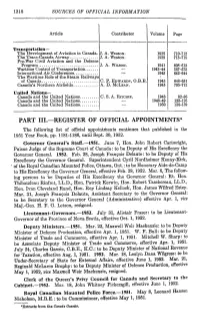

PART III.—REGISTER of OFFICIAL APPOINTMENTS* the Following List of Official Appointments Continues That Published in the 1951 Year Book, Pp

1218 SOURCES OF OFFICIAL INFORMATION Article Contributor Volume Page Transportation— The Development of Aviation in Canada. J. A. WILSON. 1938 710-712 The Trans-Canada Airway J. A. WILSON. 1938 713-715 Pre-War Civil Aviation and the Defence Program J. A. WILSON. 1941 608-612 Wartime Control of Transportation 1943-14 567-575 International Air Conferences 1945 642-644 The Wartime Role of the Steam Railways of Canada C. P. EDWARDS, O.B.E. 1945 648-651 Canada's Northern Airfields A. D. MCLEAN. 1945 705-712 United Nations- Canada and the United Nations C. S. A. RITCHIE. 1946 82-86 Canada and the United Nations 1948-49 122-125 Canada and the United Nations 1950 134-139 PART III.—REGISTER OF OFFICIAL APPOINTMENTS* The following list of official appointments continues that published in the 1951 Year Book, pp. 1181-1186, until Sept. 30, 1952. Governor General's Staff.—1951. June 7, Hon. John Robert Cartwright, Puisne Judge of the Supreme Court of Canada: to be Deputy of His Excellency the Governor General. 1952. Feb. 28, Joseph Francois Delaute: to be Deputy of His Excellency the Governor General. Superintendent Cyril Nordheimer Kenny-Kirk, of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Ottawa, Ont.: to be Honorary Aide-de-Camp to His Excellency the Governor General, effective Feb. 28, 1952. Mar. 6, The follow ing persons to be Deputies of His Excellency the Governor General: Rt. Hon. Thibaudeau Rinfret, LL.D., Hon. Patrick Kerwin, Hon. Robert Taschereau, LL.D., Hon. Ivan Cleveland Rand, Hon. Roy Lindsay Kellock, Hon. James Wilfred Estey. Mar. -

No Free Beer – R. V. Comeau and Its Effects on Inter-Provincial Trade

No Free Beer – R. v. Comeau and its Effects on Inter-Provincial Trade By Paul Chiswell and Robert Martz Today the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) released its decision in R. v. Comeau, 2018 SCC 15 (Comeau), the interprovincial free trade beer case.* The Court expanded the interpretation of section 121 of the Constitution Act by finding that s. 121 prohibits laws that in essence and purpose impede the passage of goods across provincial borders. For those who hoped the decision would constitutionally entrench a Canadian economic union or free trade in Canada, the decision is disappointing. For those who were more tempered in their expectations, the decision balances provincial autonomy with tools to strike down, not only interprovincial tariff barriers, but also "tariff- like" laws. Comeau was initially a case about beer. Mr. Comeau was charged and fined $240 for bringing a few cases of beer from Quebec to his home province of New Brunswick. Rather than pay the fine, Mr. Comeau challenged it as being unconstitutional. When his case was heard by the New Brunswick Provincial Court, Judge Leblanc, agreed and not only vacated the fine, but effectively struck down part of New Brunswick's liquor monopoly laws as unconstitutional. The case went straight to the SCC. At the SCC, Mr. Comeau argued that all trade barriers between provinces were unconstitutional. Had the SCC agreed with Mr. Comeau, this would effectively have meant the end of supply management and provincial liquor monopolies. Not surprisingly, the SCC declined to take such radical action, which could have significant effect on federal and provincial legislative schemes dealing with environmental, heath, commercial and social objectives. -

SCC File No. 37398 in the SUPREME COURT of CANADA

SCC File No. 37398 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA (On Appeal from the New Brunswick Court of Appeal) BETWEEN HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN APPLICANT (Appellant) -AND- GERARD COMEAU RESPONDENT (Respondent) RESPONDENT’S RESPONSE TO APPLICATION FOR LEAVE TO APPEAL (GERARD COMEAU, RESPONDENT) (Pursuant to Rule 27 of the Rules of The Supreme Court of Canada) GARDINER ROBERTS LLP SUPREME ADVOCACY LLP Bay Adelaide Centre, East Tower 340 Gilmour Street, Suite 100 22 Adelaide St. W., Suite 3600 Ottawa, Ontario K2P 0R3 Toronto, Ontario M5H 4E3 Marie-France Major Ian Blue Tel: (613)695-8855 Arnold Schwisberg Fax: (613)695-8580 Mikael Bernanrd Email: [email protected] Tel: (416) 865-2962 Ottawa Agent for Counsel for the Fax: (416) 865-6636 Respondent, Gerard Comeau Email: [email protected] Counsel for the Respondent, Gerard Comeau THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF NEW GOWLING WLG (CANADA) LLP BRUNSWICK Barristers and Solicitors PUBLIC PROSECUTION SERVICES 160 Elgin Street Carleton Place 26th Floor P.O. Box 6000 Ottawa, ON K1P 1C3 Fredericton, NB E3C 5H1 D. Lynne Watt William B. Richards Tel: (613) 786-8695 Kathryn A. Gregory Fax: (613) 788-3509 Tel: (506) 453-2784 Email: [email protected] Fax: (506) 453-5364 Email: [email protected] Ottawa Agent for Counsel for the Applicant Counsel for the Applicant TABLE OF CONTENTS TAB PAGE RESPONSE MEMORANDUM OF ARGUMENT PART I – OVERVIEWAD STATEMENT OF FACTS .................................................................1 Scope of the Comeau Interpretation ....................................................................................2