Getting Around Brown Desegregation, Development, and the Columbus Public Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greater Columbus Arts Council 2016 Annual Report

2016 REPORT TO THE COMMUNITY SUPPORTING ART. ADVANCING CULTURE. LETTER FROM THE BOARD CHAIR AND PRESIDENT In 2016 the Greater Columbus Arts Council made substantial progress toward building 84,031 a more sustainable arts sector in Columbus. An unprecedented year for the bed tax in 2016 resulted in more support to artists and ARTIST PROFILE arts organizations than ever before. Twenty-seven Operating Support grants were awarded totaling $3.1 million and 57 grants totaling $561,842 in Project Support. VIDEO VIEWS The Art Makes Columbus/Columbus Makes Art campaign generated nearly 400 online, print and broadcast stories, $9.1 million in publicity and 350 million earned media impressions featuring the arts and artists in Columbus. We held our first annual ColumbusMakesArt.com Columbus Open Studio & Stage October 8-9, a self-guided art tour featuring 26 artist studios, seven stages and seven community partners throughout Columbus, providing more than 1,400 direct engagements with artists in their creative spaces. We hosted another outstanding Columbus Arts Festival on the downtown riverfront 142% and Columbus’ beautiful Scioto Greenways. We estimated that more than 450,000 people enjoyed fine artists from across the country, and amazing music, dance, INCREASE theater, and local cuisine at the city’s free welcome-to-summer event. As always we are grateful to the Mayor, Columbus in website traffic City Council and the Ohio Arts Council for our funding and all the individuals, corporations and community aided by Google partners who support our work in the arts. AD GRANT PROGRAM Tom Katzenmeyer David Clifton President & CEO Board Chair arts>sports that of Columbus Nonprofit arts attendance home game sports Additional support from: The Crane Group and The Sol Morton and Dorothy Isaac, in Columbus is attendance Rebecca J. -

Columbus Near East Side BLUEPRINT for COMMUNITY INVESTMENT Acknowledgements the PARTNERS ADVISORY COMMITTEE the PACT TEAM President E

Columbus Near East Side BLUEPRINT FOR COMMUNITY INVESTMENT Acknowledgements THE PARTNERS ADVISORY COMMITTEE THE PACT TEAM President E. Gordon Gee, The Ohio State University Tim Anderson, Resident, In My Backyard Health and Wellness Program Trudy Bartley, Interim Executive Director Mayor Michael B. Coleman, City of Columbus Lela Boykin, Woodland Park Civic Association Autumn Williams, Program Director Charles Hillman, President & CEO, Columbus Metropolitan Housing Authority Bryan Brown, Columbus Metropolitan Housing Authority (CMHA) Penney Letrud, Administration & Communications Assistant (CMHA) Willis Brown, Bronzeville Neighborhood Association Dr. Steven Gabbe, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center Reverend Cynthia Burse, Bethany Presbyterian Church THE PLANNING TEAM Goody Clancy Barbara Cunningham, Poindexter Village Resident Council OVERSIGHT COMMITTEE ACP Visioning + Planning Al Edmondson, Business Owner, Mt. Vernon Avenue District Improvement Fred Ransier, Chair, PACT Association Community Research Partners Trudy Bartley, Interim Executive Director, PACT Jerry Friedman, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center Skilken Solutions Jerry Friedman, Associate Vice President, Health Services, Ohio State Wexner Columbus Policy Works Medical Center Shannon Hardin, City of Columbus Radio One Tony Brown Consulting Elizabeth Seely, Executive Director, University Hospital East Eddie Harrell, Columbus Urban League Troy Enterprises Boyce Safford, Former Director of Development, City of Columbus Stephanie Hightower, Neighborhood -

Fall 2008 Inside

the CARDINALSt. Charles Preparatory School Alumni Magazine Fall 2008 Inside September 11 was an especially poignant day for the St. Charles community as it laid to rest Mon- signor Thomas M. Bennett, one of the school’s most beloved figures. Inside you will find a tribute sec- tion to “Father” that includes a biography of his life (page 3) and a variety of photographs and spe- cial memories shared by alumni and parents (pages 4-8). Read about the gifted alumni who were presented the school’s highest honors (pages 9-11) on the Feast of St. Charles Novem- ber 4. Also read about this year’s Borromean Lecture and the com- ments delivered by Carl Anderson (pages 12-13), supreme knight of the Knights of Columbus, just two days later on November 6. In our Student News section we feature 31 seniors who were recognized by the National Merit Corporation as some of the bright- est in the nation (pages 11-12) The St. Charles community didn’t lack for something to do this summer and fall! Look inside for information and photos from the ’08 Combined Class Re- union Celebration (pages 24-25); Homecoming and the Alumni Golf Outing;(pages 28 & 33); and The Kathleen A. Cavello Mothers of St. Charles Luncheon (page 33). Our Alumni News and Class Notes sections (pages 34-45) are loaded as usual with updates, features, photos and stories about St. Charles alumni. In our Development Section read about Michael Duffy, the school’s newest Development Director (page 47) and get a recap of some of the transformational changes accomplished during the tenure of former director, Doug Stein ’78 (page 51). -

The Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia Resource Guide

The Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia Resource Guide This guide contains suggested resources, websites, articles, books, videos, films, and museums. JCM These resources are updated periodically, so please visit periodically for new information. Resources The Jim Crow Museum Virtual Tour https://my.matterport.com/show/?m=8miUGt2wCtB The Jim Crow Museum Website https://www.ferris.edu/HTMLS/news/jimcrow/ The Jim Crow Museum Timeline https://www.ferris.edu/HTMLS/news/jimcrow/timeline/homepage.htm The Jim Crow Museum Digital Collection https://sites.google.com/view/jcmdigital/home The New Jim Crow Museum Video https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=5&v=yf7jAF2Tk40&feature=emb_logo Understanding Jim Crow: using racist memorabilia to teach tolerance and promote social justice (2015) by David Pilgrim Watermelons, nooses, and straight razors: stories from the Jim Crow Museum (2018) by David Pilgrim Haste to Rise (2020) by David Pilgrim and Franklin Hughes Image from The Jim Crow Museum Collection Black Past Websites https://www.blackpast.org Black Past – African American Museums https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-museums-united-states-and-canada/ Digital Public Library of America https://dp.la EDSITEment! https://edsitement.neh.gov Equal Justice Initiative Reports https://eji.org/reports/ Facing History and Ourselves https://www.facinghistory.org Library of Congress https://www.loc.gov National Archives https://www.archives.gov National Museum of African American History & Culture https://nmaahc.si.edu PBS Learning Media https://www.pbslearningmedia.org -

Downtown Hotels and Dining Map

DOWNTOWN HOTELS AND DINING MAP DOWNTOWN HOTELS N 1 S 2 A. Moxy Columbus Short North 3 4 W. 5th Ave. E. 5th Ave. 800 N. High St. 5 E. 4th Ave. B. Graduate Columbus 6 W. 4th Ave. 7 750 N. High St. 8 9 10 14 12 11 W. 3rd Ave. Ave. Cleveland C. Le Méridien Columbus, The Joseph 13 High St. High E. 3rd Ave. 620 N. High St. 15 16 17 18 19 20 E. 2nd Ave. D. AC Hotel Columbus Downtown 21 22 W. 2nd Ave. 517 Park St. 23 24 Summit St.Summit 4th St.4th Michigan Ave. Michigan E. Hampton Inn & Suites Columbus Downtown Neil Ave. W. 1st Ave. A 501 N. High St. 25 Hubbard Ave. 28 26 27 29 F. Hilton Columbus Downtown 32 30 31 33 34 401 N. High St. 37 35 B Buttles Ave. 38 39 36 36 40 G. Hyatt Regency Columbus 42 41 Park St. Park 43 44 45 350 N. High St. Goodale Park 47 46 48 C H. Drury Inn & Suites Columbus Convention Center 50 49 670 51 Park St. Park 54 53 88 E. Nationwide Blvd. 52 1 55 56 D I. Sonesta Columbus Downtown E 57 Vine St. 58 2 4 71 33 E. Nationwide Blvd. 315 3 59 F 3rd St.3rd 4th St.4th J. Canopy by Hilton Columbus Downtown 5 1 Short North 7 6 G H Mt. Vernon Ave. Nationwide Blvd. 77 E. Nationwide Blvd. 14 Neil Ave. 8 10 Front St. Front E. Naughten St. 9 11 I J Spring St. -

Ohio PBIS Recognition Awards 2020

Ohio PBIS Recognition Awards 2020 SST Building District Level District Region Received Award Winners 1 Bryan Elementary Bryan City Bronze 1 Horizon Science Academy- Springfield Silver 1 Horizon Science Academy- Toledo Bronze 1 Fairfield Elementary Maumee City Schools Bronze 1 Fort Meigs Elementary Perrysburg Exempted Village Bronze 1 Frank Elementary Perrysburg Exempted Village Bronze 1 Hull Prairie Intermediate Perrysburg Exempted Village Bronze 1 Perrysburg Junior High School Perrysburg Exempted Village Bronze 1 Perrysburg High School Perrysburg Exempted Village Bronze 1 Toth Elementary Perrysburg Exempted Village Bronze 1 Woodland Elementary Perrysburg Exempted Village Bronze 1 Crissey Elementary Springfield Local Schools Bronze 1 Dorr Elementary Springfield Local Schools Silver 1 Old Orchard Elementary Toledo City Schools Bronze 1 Robinson Achievement Toledo City Schools Silver 2 Vincent Elementary School Clearview Local School District Bronze 2 Lorain County Early Learning Center Educational Service Center of Lorain Bronze County 2 Prospect Elementary School Elyria City Schools Bronze 2 Keystone Elementary School Keystone City Schools Silver 2 Keystone High School Keystone City Schools Silver 2 Keystone Middle School Keystone City Schools Silver 2 Midview East Intermediate School Midview Local School District Bronze 2 Midview High School Midview Local School District Bronze 2 Midview Middle School Midview Local School District Bronze 2 Midview North Elementary School Midview Local School District Bronze 2 Midview West Elementary -

Parks and Recreation Master Plan

2017-2021 FEBRUARY 28, 2017 Parks and Recreation Master Plan 2017-2021 Parks and Recreation Master Plan City of Southfi eld, Michigan Prepared by: McKenna Associates Community Planning and Design 235 East Main Street, Suite 105 Northville, Michigan 48167 tel: (248) 596-0920 fax: (248) 596-.0930 www.mcka.com ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The mission of the Southfi eld Parks and Recreation Department is to provide excellence and equal opportunity in leisure, cultural and recreational services to all of the residents of Southfi eld. Our purpose is to provide safe, educationally enriching, convenient leisure opportunities, utilizing public open space and quality leisure facilities to enhance the quality of life for Southfi eld’s total population. Administration Staff Parks and Recreation Board Terry Fields — Director, Parks & Recreation Department Rosemerry Allen Doug Block — Manager, P&R Administration Monica Fischman Stephanie Kaiser — Marketing Analyst Brandon Gray Michael A. Manion — Community Relations Director Jeannine Reese Taneisha Springer — Customer Service Ronald Roberts Amani Johnson – Student Representative Facility Supervisors Planning Department Pattie Dearie — Facility Supervisor, Beech Woods Recreation Center Terry Croad, AICP, ASLA — Director of Planning Nicole Messina — Senior Adult Facility Coordinator Jeff Spence — Assistant City Planner Jonathon Rahn — Facility Supervisor, Southfi eld Pavilion, Sarah K. Mulally, AICP — Assistant City Planner P&R Building and Burgh Park Noreen Kozlowski — Landscape Design Coordinator Golf Planning Commission Terri Anthony-Ryan — Head PGA Professional Donald Culpepper – Chairman Dan Bostick — Head Groundskeeper Steven Huntington – Vice Chairman Kathy Haag — League Information Robert Willis – Secretary Dr. LaTina Denson Parks/Park Services Staff Jeremy Griffi s Kost Kapchonick — Park Services, Park Operations Carol Peoples-Foster Linnie Taylor Parks Staff Dennis Carroll Elected Offi cials & City Administration Joel Chapman The Honorable Kenson J. -

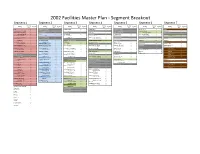

2002 Facilities Master Plan - Segment Breakout Segment 1 Segment 2 Segment 3 Segment 4 Segment 5 Segment 6 Segment 7

2002 Facilities Master Plan - Segment Breakout Segment 1 Segment 2 Segment 3 Segment 4 Segment 5 Segment 6 Segment 7 Planning Planning Planning Planning Planning Planning Planning Building Segment Building Segment Building Segment Building Segment Building Segment Building Segment Building Segment Area Area Area Area Area Area Area FHCC 1 1 Crestview MS (New) 1 2 Colerain (New) 1 3 Cranbrook ES 1 4 Everett MS (New) 1 5 Centennial HS 1 6 NWCC 1 7 New Fort Hayes MS (AIMS) 1 1 Crestview MS 1 2 Colerain 1 3 North Education Center 1 4 Everett MS 1 5 Clinton ES (New) 1 6 Avalon ES 2 7 Weinland Park ES (New) 1 1 Indianola MS 1 2 Medary ES 1 3 Salem ES 1 4 Fifth Alternative ES 1 5 Clinton ES (1922 Main Bldg)1 6 Brentnell ES 2 7 Weinland Park ES 1 1 FHHS 1 2 Winterset ES 1 3 Clinton MS 2 4 Ridgeview MS 1 5 Dominion MS (New) 1 6 East Linden ES (New) 2 1 A.G. Bell 2 2 Alpine ES (New) 2 3 Columbus Alt HS 2 4 Whetstone HS 1 5 Dominion MS 1 6 Ecole Kenwood Alt ES 1 7 East Linden ES 2 1 Gladstone ES (New) 2 2 Alpine ES 2 3 Duxberry Park Alt ES (New) 2 4 Brookhaven HS 2 5 Second Avenue ES 1 6 Hudson ES 2 7 Linden ES (New) 2 1 Gladstone ES 2 2 Arlington Park ES (New) 2 3 Duxberry Park Alt ES 2 4 Cassady Alt ES 2 5 Beechcroft HS 2 6 Innis ES 2 7 Linden ES 2 1 Huy Road ES (New) 2 2 Arlington Park ES 2 3 Gables ES (Ecole Kenwood) 1 4 Linmoor MS 2 5 Liberty ES 3 6 Mifflin HS 2 7 South Mifflin ES (New) 2 1 Huy Road ES 2 2 CSIA (New) 2 3 Indian Springs ES 1 3 Medina MS 2 5 Beery MS 4 6 NECC 2 7 South Mifflin ES 2 1 Indianola Alt ES 1 2 CSIA 2 3 McGuffey ES -

Ohio's 3Rd District (Joyce Beatty - D) Through 2018 LIHTC Properties in Ohio's 3Rd District Through 2018

LIHTC Properties in Ohio's 3rd District (Joyce Beatty - D) Through 2018 LIHTC Properties in Ohio's 3rd District Through 2018 Annual Low Rent or HUD Multi-Family Nonprofit Allocation Total Tax-Exempt Project Name Address City State Zip Code Allocated Year PIS Construction Type Income Income Credit % Financing/ Sponsor Year Units Bond Amount Units Ceiling Rental Assistance Both 30% 1951 PARSONS REBUILDING LIVES I COLUMBUS OH 43207 Yes 2000 $130,415 2000 Acquisition and Rehab 25 25 60% AMGI and 70% No AVE present value 3401 QUINLAN CANAL Not STRATFORD EAST APTS OH 43110 Yes 1998 $172,562 2000 New Construction 82 41 BLVD WINCHESTER Indicated 4855 PINTAIL CANAL 30 % present MEADOWS OH 43110 Yes 2001 $285,321 2000 New Construction 95 95 60% AMGI Yes CREEK DR WINCHESTER value WHITEHALL SENIOR 851 COUNTRY 70 % present WHITEHALL OH 43213 Yes 2000 $157,144 2000 New Construction 41 28 60% AMGI No HOUSING CLUB RD value 6225 TIGER 30 % present GOLF POINTE APTS GALLOWAY OH 43119 No 2002 $591,341 2001 Acquisition and Rehab 228 228 Yes WOODS WAY value GREATER LINDEN 533 E STARR 70 % present COLUMBUS OH 43201 Yes 2001 $448,791 2001 New Construction 39 39 50% AMGI No HOMES AVE value 423 HILLTOP SENIOR 70 % present OVERSTREET COLUMBUS OH 43228 Yes 2001 $404,834 2001 New Construction 100 80 60% AMGI No VILLAGE value WAY Both 30% 684 BRIXHAM KINGSFORD HOMES COLUMBUS OH 43204 Yes 2002 $292,856 2001 New Construction 33 33 60% AMGI and 70% RD present value 30 % present REGENCY ARMS APTS 2870 PARLIN DR GROVE CITY OH 43123 No 2002 $227,691 2001 Acquisition and -

And Justice for All: Indiana’S Federal Courts

And Justice for All: Indiana’s Federal Courts Teacher’s Guide Made possible with the support of The Historical Society of the United States District Court for the Southern District of Indiana, Inc. Indiana Historical Society Heritage Support Grants are provided by the Indiana Historical Society and made possible by Lilly Endowment, Inc. The R. B. Annis Educational Foundation Indiana Bar Association This is a publication of Gudaitis Production 2707 S. Melissa Court 812-360-9011 Bloomington, IN 47401 Copyright 2017 The Historical Society of the United States District Court for the Southern District of Indiana, Inc. All rights reserved The text of this publication may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the written permission of the copyright owner. All inquiries should be addressed to Gudaitis Production. Printed in the United States of America Contents Credits ............................................................................................................................iv Introduction .....................................................................................................................1 Curriculum Connection ..................................................................................................1 Objectives ........................................................................................................................3 Video Program Summary ...............................................................................................3 -

Child Care Access in 2020

Summer 2019 CHILD CARE ACCESS IN 2020: How will pending state mandates affect availability in Franklin County, Ohio? Abel J. Koury, Ph.D., Jamie O’Leary, MPA, Laura Justice, Ph.D., Jessica A.R. Logan, Ph.D., James Uanhoro INTRODUCTION AND PURPOSE Child care provision is a critical service for children and their families, and it can also bolster the workforce and larger economy. For child care to truly be beneficial, however, it must be affordable, accessible, and high quality. A current state requirement regarding child care programming may have enormous implications for many of Ohio’s most vulnerable families who rely on funding for child care. Specifically, by 2020, any Ohio child care provider that accepts Publicly Funded Child Care (PFCC) subsidies must both apply to and receive entry into Ohio’s quality rating and improvement system – Step Up To Quality (SUTQ) (the “2020 mandate”). The purpose of this paper is two-fold. First, we aim to provide an in-depth examination of the availability of child care in Franklin County, Ohio, with a specific focus on PFCC-accepting programs, and explore how this landscape may change in July of 2020. Second, we aim to examine the locations of programs that are most at risk for losing child care sites, highlighting possible deserts through the use of mapping. Crane Center for Early Childhood Research and Policy Improving children’s well-being through research, practice, and policy.1 2020 SUTQ Mandate: What is at stake? According to an analysis completed by Franklin County Jobs and Family Services (JFS), if the 2020 mandate went into effect today, over 21,000 young children would lose their care (Franklin County Jobs and Family Services, 2019). -

African Americans and the Color Line in Ohio, 1915-1930

“Giffin fills an essential gap and takes on a crucial, yet little-studied time period in history. Perhaps more important is the depth and quality of his research combined with his important and nuanced arguments about the hardening of OHIO OHIO OHIO the color line in Ohio urban areas between 1915 and 1930. This book will find STATE STATE STATE sizeable and significant audiences for a long time to come.” —James H. Madison, Indiana University Afric “An exhaustive and fascinating study of race and community.” —Kevin J. Mumford, University of Iowa Writing in true social history tradition, William W. Giffin presents a magisterial study of African Americans focusing on times that saw the culmination of an trends that were fundamentally important in shaping the twentieth century. While many scholars have examined African Americans in the South and such Americ large cities as New York and Chicago during this time, other important urban in Ohio, 1915–1930 areas have been ignored. Ohio, with its large but very different urban cen- ters—notably, Cleveland, Columbus, and Cincinnati—provides Giffin with the wealth of statistical data and qualitative material that he uses to argue that the African Americans “color line” in Ohio hardened during this time period as the Great Migration gained force. His data shows, too, that the color line varied according to urban area—it hardened progressively as one traveled South in the state. In addition, ans and the Color Line whereas previous studies have concentrated on activism at the national level through such groups as the NAACP, Giffin shows how African American men and women in Ohio constantly negotiated the color line on a local level, and the through both resistance and accommodation on a daily and very interpersonal in Ohio, 1915–1930 level with whites, other blacks, and people of different ethnic, class, and racial backgrounds.