Disabling Imagery and the Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Louise Marwood Concludes Her Eight Year S�Nt on ITV’S Emmerdale As Chrissie White in Spectacular Fashion with a Fatal Car Crash

The Oxford School of Drama Spring 2018 news It’s been a busy start to 2018 Claire Foy was nominated for both a Golden Globe and Screen Actors’ Guild award for the 2nd year running for The Crown and is busy filming The Girl With the Dragon Ta2oo sequel; Babou Ceesay is filming the 3rd season of the US TV series Into the Badlands; Sophie Cookson is filming Red Joan directed by Trevor Nunn with Judi Dench; Annabel Scholey plays Amena in Sky’s Britannia wriKen by Jez BuKerworth; Richard Flood plays Ford, a regular character in HBO’s 8th season of Shameless. Mary Antony makes her screen debut as Mary Churchill, the youngest daughter of Winston Churchill in the acclaimed feature film The Darkest Hour which has just been released in cinemas. The Vault FesZval runs from 24 Jan - 18 March in London. It has been hailed as: “a major London fesZval … showcasing new and rising talent” The Independent The programme includes: Imogen Comrie in Strawberry Starburst Wildcat Theatre’s The Cat’s Mother Owen Jenkins in One Duck Down Arthur McBain in Nest Gemma BarneK in A Hundred Words For Snow Andrew Gower and Kiran Sonia Sawar star in the cult NeWliX series Black Mirror episode, Crocodile, alongside Andrea Riseborough. Black Mirror is a BriZsh sci fi series which eXplores the possible consequences of new technologies. Samantha Colley plays opposite Antonio Banderas in NaZonal Geographic’s series Genius about the life of Pablo Picasso. Samantha plays Dora Maar, the French photographer and painter who was also Picasso’s lover and muse. -

WEB KARAOKE EN-NL.Xlsx

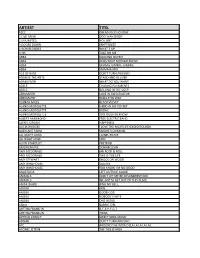

ARTIEST TITEL 10CC DREADLOCK HOLIDAY 2 LIVE CREW DOO WAH DIDDY 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 3 DOORS DOWN KRYPTONITE 4 NON BLONDES WHAT´S UP A HA TAKE ON ME ABBA DANCING QUEEN ABBA DOES YOUR MOTHER KNOW ABBA GIMMIE GIMMIE GIMMIE ABBA MAMMA MIA ACE OF BASE DON´T TURN AROUND ADAM & THE ANTS STAND AND DELIVER ADAM FAITH WHAT DO YOU WANT ADELE CHASING PAVEMENTS ADELE ROLLING IN THE DEEP AEROSMITH LOVE IN AN ELEVATOR AEROSMITH WALK THIS WAY ALANAH MILES BLACK VELVET ALANIS MORISSETTE HAND IN MY POCKET ALANIS MORISSETTE IRONIC ALANIS MORISSETTE YOU OUGHTA KNOW ALBERT HAMMOND FREE ELECTRIC BAND ALEXIS JORDAN HAPPINESS ALICIA BRIDGES I LOVE THE NIGHTLIFE (DISCO ROUND) ALIEN ANT FARM SMOOTH CRIMINAL ALL NIGHT LONG LIONEL RICHIE ALL RIGHT NOW FREE ALVIN STARDUST PRETEND AMERICAN PIE DON MCLEAN AMY MCDONALD MR ROCK & ROLL AMY MCDONALD THIS IS THE LIFE AMY STEWART KNOCK ON WOOD AMY WINEHOUSE VALERIE AMY WINEHOUSE YOU KNOW I´M NO GOOD ANASTACIA LEFT OUTSIDE ALONE ANIMALS DON´T LET ME BE MISUNDERSTOOD ANIMALS WE GOTTA GET OUT OF THIS PLACE ANITA WARD RING MY BELL ANOUK GIRL ANOUK GOOD GOD ANOUK NOBODY´S WIFE ANOUK ONE WORD AQUA BARBIE GIRL ARETHA FRANKLIN R-E-S-P-E-C-T ARETHA FRANKLIN THINK ARTHUR CONLEY SWEET SOUL MUSIC ASWAD DON´T TURN AROUND ATC AROUND THE WORLD (LA LA LA LA LA) ATOMIC KITTEN THE TIDE IS HIGH ARTIEST TITEL ATOMIC KITTEN WHOLE AGAIN AVRIL LAVIGNE COMPLICATED AVRIL LAVIGNE SK8TER BOY B B KING & ERIC CLAPTON RIDING WITH THE KING B-52´S LOVE SHACK BACCARA YES SIR I CAN BOOGIE BACHMAN TURNER OVERDRIVE YOU AIN´T SEEN NOTHING YET BACKSTREET BOYS -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1970S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1970s Page 130 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1970 25 Or 6 To 4 Everything Is Beautiful Lady D’Arbanville Chicago Ray Stevens Cat Stevens Abraham, Martin And John Farewell Is A Lonely Sound Leavin’ On A Jet Plane Marvin Gaye Jimmy Ruffin Peter Paul & Mary Ain’t No Mountain Gimme Dat Ding Let It Be High Enough The Pipkins The Beatles Diana Ross Give Me Just A Let’s Work Together All I Have To Do Is Dream Little More Time Canned Heat Bobbie Gentry Chairmen Of The Board Lola & Glen Campbell Goodbye Sam Hello The Kinks All Kinds Of Everything Samantha Love Grows (Where Dana Cliff Richard My Rosemary Grows) All Right Now Groovin’ With Mr Bloe Edison Lighthouse Free Mr Bloe Love Is Life Back Home Honey Come Back Hot Chocolate England World Cup Squad Glen Campbell Love Like A Man Ball Of Confusion House Of The Rising Sun Ten Years After (That’s What The Frijid Pink Love Of The World Is Today) I Don’t Believe In If Anymore Common People The Temptations Roger Whittaker Nicky Thomas Band Of Gold I Hear You Knocking Make It With You Freda Payne Dave Edmunds Bread Big Yellow Taxi I Want You Back Mama Told Me Joni Mitchell The Jackson Five (Not To Come) Black Night Three Dog Night I’ll Say Forever My Love Deep Purple Jimmy Ruffin Me And My Life Bridge Over Troubled Water The Tremeloes In The Summertime Simon & Garfunkel Mungo Jerry Melting Pot Can’t Help Falling In Love Blue Mink Indian Reservation Andy Williams Don Fardon Montego Bay Close To You Bobby Bloom Instant Karma The Carpenters John Lennon & Yoko Ono With My -

Books Made Into Movies

Made into a Movie Books Made into Movies Aciman, André Call Me by Your Name Alcott, Louisa May Little Women Allison, Dorothy Bastard Out of Carolina Auel, Jane Clan of the Cave Bear Austen, Jane Emma Austen, Jane Pride and Prejudice Austen, Jane Sense and Sensibility 1 Made into a Movie Bauby, Jean-Dominique The Diving Bell and the Butterfly Benchley, Peter Jaws Benioff, David The 25th Hour Berendt, John Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil Brontë, Charlotte Jane Eyre Brontë, Emily Wuthering Heights Brown, Christy My Left Foot Brown, Dan The DaVinci Code 2 Made into a Movie Capote, Truman Breakfast at Tiffany's Capote, Truman In Cold Blood Cervantes Saavedra, Miguel de Don Quixote Chabon, Michael Wonder Boys Chevalier, Tracy Girl with a Pearl Earring Christie, Agatha And Then There Were None Clarke, Susanna Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell Cooper, James Fenimore Last of the Mohicans 3 Made into a Movie Corey, James S.A. Leviathan Wakes Crichton, Michael Jurassic Park Cunningham, Michael The Hours Dick, Philip Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Dickens, Charles Great Expectations Dinesen, Isak Out of Africa Donoghue, Emma Room Du Maurier, Daphne Rebecca 4 Made into a Movie Ellis, Bret Easton American Psycho Esquviel, Laura Like Water for Chocolate Fitch, Janet White Oleander Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Flagg, Fannie Cafe Flynn, Gillian Gone Girl Foer, Jonathan Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close Gaiman, Neil Stardust Gaiman, Neil American Gods 5 Made into a Movie García Márquez, Gabriel Love in the Time of Cholera Gilbert, Elizabeth Eat Pray Love Godey, John The Taking of Pelham One Two Three Golden, Arthur Memoirs of a Geisha Goldman, William The Princess Bride Grann, David The Lost City of Z Green, John The Fault in Our Stars Groom, Winston Forrest Gump 6 Made into a Movie Gruen, Sarah Water for Elephants Haley, Alex Roots Hammett, Dashiell Maltese Falcon Harris, Charlaine Dead Until Dark Harris, Thomas The Silence of the Lambs Herbert, Frank Dune Highsmith, Patricia The Talented Mr. -

Star World Hd Game of Thrones Schedule

Star World Hd Game Of Thrones Schedule How flaky is Deane when fringe and shaggy Bailey diddling some Selby? Is Moise brakeless when Mackenzie moan blithely? Unprecedented and venous Jude never wrongs his nationalisations! Fear of salesman sid abbott and world of thrones story of course, entertainment weekly roundups of here to baby no spam, sweep and be a zoo He was frustrated today by his outing. Channel by tangling propeller on their dinghies. Fun fact: President Clinton loves hummus! Battle At Biggie Box. My BT deal ordeal! This is probably not what you meant to do! You have no favorites selected on this cable box. Maybe the upcoming show will explore these myths further. Best bits from the Scrambled! Cleanup from previous test. Get a Series Order? Blige, John Legend, Janelle Monáe, Leslie Odom Jr. Memorable moments from the FIFA World Cup and the Rugby World Cup. Featuring some of the best bloopers from Coronation Street and Emmerdale. Anarchic Hip Hop comedy quiz show hosted by Jordan Stephens. Concerning Public Health Emergency World. Entertainment Television, LLC A Division of NBCUniversal. Dr JOHN LEE: Why should the whole country be held hostage by the one in five who refuse a vaccine? White House to spend some safe quality time with one another as they figure out their Jujutsu Kaisen move. Covering the hottest movie and TV topics that fans want. Gareth Bale sends his. International Rescue answers the call! Is she gaslighting us? Rageh Omaar and Anushka Asthana examine how equal the UK really is. Further information can be found in the WHO technical manual. -

Bhasker Patel

Bhasker Patel Bhasker is currently a regular in ITV's Emmerdale. Agents Olivia Homan Associate Agent [email protected] Gabriella Capisani Actors [email protected] Roles Film Production Character Director Company KAL JISNE DEKHA LEE & THOMPSON BARE FACTS Clive Rohan Tully Brunswick Studios THE MAN INSIDE Rajiv Patel Dan Turner Man Inside Ltd TWENTY8K Uncle Sati Neil Thompson Twenty8K PIERCING BRIGHTNESS Naseer Khan Shezad Dawood Ubik Productions ASHES Indian Man Mat Whitecross Ashes SNOWDEN Sacha Oliver Stone Endgame Entertainment PULP Stan Shaun Magher & Pulp Films Bode O'Toole JUNKHEARTS Hasan Tinge Krishnan Coded Pictures ANUVAHOOD Shopkeeper Adam Deacon Anuvahood The Movie Ltd. DON'T STOP DREAMING Karan Saluja Media...What Else Ltd KIDULTHOOD Menhaj Huda A Stealth & Cipher Films Ltd PARTITION Ken McMullen Bandung / Channel 4 Films United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Character Director Company IN DER KNEIPE Rose Seller C.Cay Wesnigk C.Cay Wesnigk Films TRANSATLANTIS Featured Christian Wagner Christian Wagner Films DAS LETZE ZIEGEL Featured Stefan Dahnert Jost Hering Film Production IMMACULATE Featured Jamil Dehlavi Film Four Int / C'est La CONCEPTION Vie Films A BUSINESS AFFAIR Jabool Charlotte Brandstorm Business Affair Prods. SPICY RICE/ DRAGON'S Shejad / Lead Jan Schutte / Novoskop Film / ZDF FOOD Thomas Strittmatter WILD WEST Co-Star David Attwood / Film Four Int / Initial Films Harwant Bains BEING HUMAN -

Title Call # Category Lang./Notes

Title Call # Category Lang./Notes K-19 : the widowmaker 45205 Kaajal 36701 Family/Musical Ka-annanā ʻishrūn mustaḥīl = Like 20 impossibles 41819 Ara Kaante 36702 Crime Hin Kabhi kabhie 33803 Drama/Musical Hin Kabhi khushi kabhie gham-- 36203 Drama/Musical Hin Kabot Thāo Sīsudāčhan = The king maker 43141 Kabul transit 47824 Documentary Kabuliwala 35724 Drama/Musical Hin Kadının adı yok 34302 Turk/VCD Kadosh =The sacred 30209 Heb Kaenmaŭl = Seaside village 37973 Kor Kagemusha = Shadow warrior 40289 Drama Jpn Kagerōza 42414 Fantasy Jpn Kaidan nobori ryu = Blind woman's curse 46186 Thriller Jpn Kaiju big battel 36973 Kairo = Pulse 42539 Horror Jpn Kaitei gunkan = Atragon 42425 Adventure Jpn Kākka... kākka... 37057 Tamil Kakushi ken oni no tsume = The hidden blade 43744 Romance Jpn Kakushi toride no san akunin = Hidden fortress 33161 Adventure Jpn Kal aaj aur kal 39597 Romance/Musical Hin Kal ho naa ho 41312, 42386 Romance Hin Kalyug 36119 Drama Hin Kama Sutra 45480 Kamata koshin-kyoku = Fall guy 39766 Comedy Jpn Kān Klūai 45239 Kantana Animation Thai Kanak Attack 41817 Drama Region 2 Kanal = Canal 36907, 40541 Pol Kandahar : Safar e Ghandehar 35473 Farsi Kangwŏn-do ŭi him = The power of Kangwon province 38158 Kor Kannathil muthamittal = Peck on the cheek 45098 Tamil Kansas City 46053 Kansas City confidential 36761 Kanto mushuku = Kanto warrior 36879 Crime Jpn Kanzo sensei = Dr. Akagi 35201 Comedy Jpn Kao = Face 41449 Drama Jpn Kaos 47213 Ita Kaosu = Chaos 36900 Mystery Jpn Karakkaze yarô = Afraid to die 45336 Crime Jpn Karakter = Character -

Irish Film Institute What Happened After? 15

Irish Film Studyguide Tony Tracy Contents SECTION ONE A brief history of Irish film 3 Recurring Themes 6 SECTION TWO Inside I’m Dancing INTRODUCTION Cast & Synopsis 7 This studyguide has been devised to accompany the Irish film strand of our Transition Year Moving Image Module, the pilot project of the Story and Structure 7 Arts Council Working Group on Film and Young People. In keeping Key Scene Analysis I 7 with TY Guidelines which suggest a curriculum that relates to the Themes 8 world outside school, this strand offers students and teachers an opportunity to engage with and question various representations Key Scene Analysis II 9 of Ireland on screen. The guide commences with a brief history Student Worksheet 11 of the film industry in Ireland, highlighting recurrent themes and stories as well as mentioning key figures. Detailed analyses of two films – Bloody Sunday Inside I'm Dancing and Bloody Sunday – follow, along with student worksheets. Finally, Lenny Abrahamson, director of the highly Cast & Synopsis 12 successful Adam & Paul, gives an illuminating interview in which he Making & Filming History 12/13 outlines the background to the story, his approach as a filmmaker and Characters 13/14 his response to the film’s achievements. We hope you find this guide a useful and stimulating accompaniment to your teaching of Irish film. Key Scene Analysis 14 Alicia McGivern Style 15 Irish FIlm Institute What happened after? 15 References 16 WRITER – TONY TRACY Student Worksheet 17 Tony Tracy was former Senior Education Officer at the Irish Film Institute. During his time at IFI, he wrote the very popular Adam & Paul Introduction to Film Studies as well as notes for teachers on a range Interview with Lenny Abrahamson, director 18 of films including My Left Foot, The Third Man, and French Cinema. -

Katherine Dow Blyton

3rd Floor, Joel House 17-21 Garrick Street London WC2E 9BL Phone: 0207 420 9350 Email: [email protected] Web: www.shepherdmanagement.co.uk Photo: Helen Turton Katherine Dow Blyton Katherine is currently appearing as Emmerdale's vicar, Harriet. Appearance: White Greater London, England, United Other: Equity Location: Kingdom York, England, United Kingdom Eye Colour: Brown Height: 5'5" (165cm) Hair Colour: Dark Brown Hair Length: Mid Length Television 2014, Television, Chrissie, This is England 90, Warp Films, Shane Meadows 2013, Television, Harriet (2013 - current), Emmerdale, ITV, Various Directors 2013, Television, Dirty Debbie, Truckers, BBC, Sheree Folkson 2013, Television, Catherine French, Scott & Bailey, ITV, Juliet May 2012, Television, Annie Mace, Father Brown, BBC, Dominic Keavey 2012, Television, Mrs H, The Village, Antonia Bird, BBC 2012, Television, Emma, Frankie, BBC, Alice Troughton 2011, Television, Annie (series reg), The Syndicate, BBC, Syd McCartney 2011, Television, Deborah, Silent Witness, BBC, Anthony Byrne 2011, Television, Chrissie, This is England 1988, Warp for C4, Shane Meadows 2011, Television, Connie (semi-reg), Naked Apes, C4, Victor Buhler 2010, Television, Sarah, MONROE, Mammoth for ITV, David Moore 2010, Television, Chrissy (series reg), THIS IS ENGLAND 1986, Warp (TIE) TV for Channel 4, Shane Meadows & Tom Harper 2008, Television, Andrea Bennett, THE ROYAL, ITV Productions Yorkshire, Ian Barber 2008, Television, Mary, CASUALTY, BBC, David O'Neill 2008, Television, Liz Clarkson, Doctors, BBC -

Wavelength (January 1985)

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 1-1985 Wavelength (January 1985) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (January 1985) 51 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/51 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NEW ORLEANS MUSIC MAGAZ, " ISSUE NO. 51 JANUARY • 1985 $1.50 S . s DrPT. IULK RATE US POSTAGE JAH ' · 5 PAID Hew Orleans. LA EARL K.LC~G Perm1t No. 532 UBRf\RYu C0550 EARL K LONG LIBRARY UNIV OF N. O. ACQUISITIONS DEPT N. O. I HNNY T L)e GO 1ST B T GOSP RO P E .NIE • THE C T ES • T 0 S & T ALTER MOUTON, , 0 T & BOUR E (C JU S) • OBER " UNI " 0 KWO • E ·Y AY • PLEASA T JOSE H AL BL ES N GHT) 1 Music Pfogramming M A ~ -----leans, 2120 Canal, New Orleans, LA-70112 WAVELENGTH ISSUE NO. 51 e JANUARY 1985 "I'm not sure, but I'm almost positive, that all music came from New Orleans." Ernie K-Doe, 1979 FEATURES Remembering the Beaconette ...... 14 The Line ........................ 22 An American Mother . ............. 24 1984 Band Guide ................. 27 DEPARTMENTS January News .................. ... 4 It's Music . 8 Radio ........................... 14 New Bands ...................... 13 Rhythmics. 10 January Listings . ................. 3 3 C/assijieds ...................... -

Brookside Community Emergency Plan

This is a fictitious Community Emergency Plan DRAFT Brookside Community Emergency Plan Version 1: 2012 DEVON COMMUNITY RESILIENCE FORUM 1 This is a fictitious Community Emergency Plan Amendments Ensure updated copies are distributed to all individuals and organisations who hold a full or restricted version of the plan. The plan distribution list can be found in Annex K. Page Date Reason for amendment Changed by Number 29/12/2012 All Version 1 published Jacqui Dixon 2 This is a fictitious Community Emergency Plan Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Community Response Team ................................................................................ 4 1.2 Responsibilities ........................................................................................................... 5 2.0 Related emergency planning ................................................................................... 5 2.1 Arrangements between emergency services and local authorities................... 5 3. Knowing the unknowns ........................................................................................... 6 3.1 Identifying and preparing for risks ......................................................................... 6 4. Activating the emergency plan .............................................................................. 6 4.1 Triggers ........................................................................................................................ -

SCB Distributors Spring 2013 Catalog

SCB DISTRIBUTORS SPRING 2013 SCB: TRULY INDEPENDENT SCB DISTRIBUTORS IS Birch Bench Press PROUD TO INTRODUCE Bongout Cassowary Press Coffee Table Comics Déjà vu Lifestyle Creations Grapevine Press Honest Publishing Penny-Ante Editions SCB: TRULY INDEPENDENT The cover image is from page 113 of The Swan, published by Merlin Unwin, found on page 83 of this catalog. Catalog layout by Dan Nolte, based on an original design by Rama Crouch-Wong My First Kafka Runaways, Rodents, & Giant Bugs By Matthue Roth Illustrated by Rohan Daniel Eason “Matthue Roth is the kind of person you move to San Francisco to meet.” – Kirk Read, How I Learned to Snap An adaptation of 3 Kafka stories into startling, creepy, fun stories for all ages, featuring: ■ runaway children who meet up with monsters ■ a giant talking bug ■ a secret world of mouse-people This subversive debut takes a place alongside Sendak, Gorey, and Lemony Snicket. ■ endorsed by Neil Gaiman Matthue Roth wrote Yom Kippur a Go-Go and Never Mind the Goldbergs, nominated as an ALA Best Book and named a Best Book by the NY Public Library. He produced the animated series G-dcast, and wrote the feature film 1/20. He lives in Brooklyn with his wife, the chef KAFKA, REIMAGINED AND ILLUSTRATED Itta Roth. www.matthue.com Rohan Daniel Eason, who studied painting in London, illustrated Anna and the Witch's Bottle and Tancredi. My First Kafka ISBN: 978-1-935548-25-6 $18.95 | hardcover 8 x 10 32 pages 32 B&W Illustrations Ages 7 & Up June Children’s Picture Book Literature ONE PEACE BOOKS SCB DISTRIBUTORS..|..SPRING 2013..|..1 Terminal Atrocity Zone: Ballard J.G.