SPORTS PROGRAMMING in SMALL MARKET RADIO Eugene Delisio A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roy Sievers “A Hero May Die, but His Memory Lives On” ©Diamondsinthedusk.Com by BILL HASS I Had Missed It in the Sports Section and on the Internet

Roy Sievers “A Hero may die, but his memory lives on” ©DiamondsintheDusk.com By BILL HASS I had missed it in the sports section and on the internet. A friend of my mentioned it to me and sent me a link to the story. On April 3 – ironically, right at the start of the 2017 baseball season – Roy Sievers died at age 90. I felt a pang of deep sadness. After all, no matter how old you get, the little kid in you expects your heroes to live for- ever. As the years passed and I didn’t see any kind of obitu- ary on Sievers, I thought perhaps he might actually do that. I knew better, of course. Sometimes reality has a way of intruding on your impossible dreams, and maybe it’s just as well. I have never been much for having heroes. Oh, there are plenty of people I have admired and some of them have done heroic things. But a hero is someone who stays constant, someone you root for no matter what, and people in sports lend themselves to that. Roy Sievers was a genuine hero for me, and, really, the only athlete I ever put in that category. Let me explain why. In the early 1950s, when I first became aware of baseball, my family lived in the northern Virginia suburbs of Wash- ington, D.C. I rooted for the Washington Senators (known to their fans as the “Nats”), to whom the adjective “downtrod- den” was constantly applied, if not invented. Prior to the 1954 season, the Nats obtained Sievers in a trade with the Baltimore Orioles, formerly the St. -

Yankee Stadium and the Politics of New York

The Diamond in the Bronx: Yankee Stadium and The Politics of New York NEIL J. SULLIVAN OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS THE DIAMOND IN THE BRONX This page intentionally left blank THE DIAMOND IN THE BRONX yankee stadium and the politics of new york N EIL J. SULLIVAN 1 3 Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogotá Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris São Paolo Shanghai Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Copyright © 2001 by Oxford University Press Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available. ISBN 0-19-512360-3 135798642 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper For Carol Murray and In loving memory of Tom Murray This page intentionally left blank Contents acknowledgments ix introduction xi 1 opening day 1 2 tammany baseball 11 3 the crowd 35 4 the ruppert era 57 5 selling the stadium 77 6 the race factor 97 7 cbs and the stadium deal 117 8 the city and its stadium 145 9 the stadium game in new york 163 10 stadium welfare, politics, 179 and the public interest notes 199 index 213 This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgments This idea for this book was the product of countless conversations about baseball and politics with many friends over many years. -

The Cubs Win the World Series!

Can’t-miss listening is Pat Hughes’ ‘The Cubs Win the World Series!’ CD By George Castle, CBM Historian Posted Monday, January 2, 2017 What better way for Pat Hughes to honor his own achievement by reminding listeners on his new CD he’s the first Cubs broadcaster to say the memorable words, “The Cubs win the World Series.” Hughes’ broadcast on 670-The Score was the only Chi- cago version, radio or TV, of the hyper-historic early hours of Nov. 3, 2016 in Cleveland. Radio was still in the Marconi experimental stage in 1908, the last time the Cubs won the World Series. Baseball was not broadcast on radio until 1921. The five World Series the Cubs played in the radio era – 1929, 1932, 1935, 1938 and 1945 – would not have had classic announc- ers like Bob Elson claiming a Cubs victory. Given the unbroken drumbeat of championship fail- ure, there never has been a season tribute record or CD for Cubs radio calls. The “Great Moments in Cubs Pat Hughes was a one-man gang in History” record was produced in the off-season of producing and starring in “The Cubs 1970-71 by Jack Brickhouse and sidekick Jack Rosen- Win the World Series!” CD. berg. But without a World Series title, the commemo- ration featured highlights of the near-miss 1969-70 seasons, tapped the WGN archives for older calls and backtracked to re-creations of plays as far back as the 1930s. Did I miss it, or was there no commemorative CD with John Rooney, et. -

The Texas Observer APRIL 17, 1964

The Texas Observer APRIL 17, 1964 A Journal of Free Voices A Window to The South 25c A Photograph Sen. Ralph Yarborough • • •RuBy ss eII lee we can be sure. Let us therefore recall, as we enter this crucial fortnight, what we iciaJ gen. Jhere know about Ralph Yarborough. We know that he is a good man. Get to work for Ralph Yarborough! That is disputed, for some voters will choose to We know that he is courageous. He has is the unmistakable meaning of the front believe the original report. not done everything liberals wanted him to page of the Dallas Morning News last Sun- Furthermore, we know, from listening to as quickly as we'd hoped, but in the terms day. The reactionary power structure is Gordon McLendon, that he is the low- of today's issues and the realities in Texas, out to get Sen. Yarborough, and they will, downest political fighter in Texas politics he has been as courageous a defender of unless the good and honest loyal Demo- since Allan Shivers. Who but an unscrupu- the best American values and the rights of crats of Texas who have known him for lous politician would call such a fine public every person of every color as Sam Hous- the good and honest man he is lo these servant as Yarborough, in a passage bear- ton was; he has earned a secure place in many years get to work now and stay at it ing on the assassination and its aftermath, Texas history alongside Houston, Reagan, until 7 p.m. -

PRO FOOTBALL HALL of FAME TEACHER ACTIVITY GUIDE 2020-2021 Edition

PRO FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME TEACHER ACTIVITY GUIDE 2020-2021 EDITIOn Quarterback Joe Namath - Hall of fame class of 1985 nEW YORK JETS Team History The history of the New York franchise in the American Football League is the story of two distinct organizations, the Titans and the Jets. Interlocking the two in continuity is the player personnel which went with the franchise in the ownership change from Harry Wismer to a five-man group headed by David “Sonny” Werblin in February 1963. The three-year reign of Wismer, who was granted a charter AFL franchise in 1959, was fraught with controversy. The on-the-field happenings of the Titans were often overlooked, even in victory, as Wismer moved from feud to feud with the thoughtlessness of one playing Russian roulette with all chambers loaded. In spite of it all, the Titans had reasonable success on the field but they were a box office disaster. Werblin’s group purchased the bankrupt franchise for $1,000,000, changed the team name to Jets and hired Weeb Ewbank as head coach. In 1964, the Jets moved from the antiquated Polo Grounds to newly- constructed Shea Stadium, where the Jets set an AFL attendance mark of 45,665 in the season opener against the Denver Broncos. Ewbank, who had enjoyed championship success with the Baltimore Colts in the 1950s, patiently began a building program that received a major transfusion on January 2, 1965 when Werblin signed Alabama quarterback Joe Namath to a rumored $400,000 contract. The signing of the highly-regarded Namath proved to be a major factor in the eventual end of the AFL-NFL pro football war of the 1960s. -

Baseball Day Two Oct 1, 2009 775

766. Wyatt Earp 1870 Signed Subpoena Resourceful, to say the very least, Wyatt Earp wore the hat of farmer, buffalo hunter, miner and boxing referee (among other endeavors) long before embrac- ing his role at the O.K. Corral. The offered display is an incredibly scarce “Wild West” find: a legal docu- ment signed by Earp. To begin with, Earp’s penning is among the most rare of men of his ilk. Sweetening the pot further is the fact that this bold signature was exe- cuted in a lawman’s capacity. All of 21 years old with volumes of lawless activity still years ahead, Earp, acting as the Barton County, Missouri local constable, penned this subpoena to be served to one Mr. Thomas G. Harvey, informing said party that he would have to testify within a fortnight in the case of Missouri vs. Thomas Brown. Arranged in a handsome 25-3/4 x 17- 1/2” wooden frame, the 7-3/4 x 4-3/4” original docu- ment (shown on the reverse, penned entirely in Earp’s hand) is displayed below a photocopy of the front so that both sides can be viewed simultaneously. On the reverse, Earp has inscribed: “I have served the within summons upon the within named Thomas G. Harvey by reading the same to him this Feb 28, 1870 - W.S. Earp, Const.” The black-ink fountain pen content is crisply executed with Earp’s endorsement projecting (“9-10”) quality. The piece is affected by a small tear at the far left, (3) tiny slashes near the upper portion and a horizontal compacting fold. -

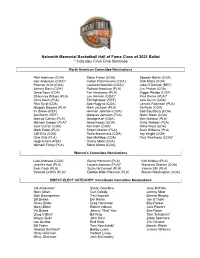

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame Class of 2021 Ballot * Indicates First-Time Nominee

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame Class of 2021 Ballot * Indicates First-Time Nominee North American Committee Nominations Rick Adelman (COA) Steve Fisher (COA) Speedy Morris (COA) Ken Anderson (COA)* Cotton Fitzsimmons (COA) Dick Motta (COA) Fletcher Arritt (COA) Leonard Hamilton (COA)* Jake O’Donnell (REF) Johnny Bach (COA) Richard Hamilton (PLA) Jim Phelan (COA) Gene Bess (COA) Tim Hardaway (PLA) Digger Phelps (COA) Chauncey Billups (PLA) Lou Henson (COA)* Paul Pierce (PLA)* Chris Bosh (PLA) Ed Hightower (REF) Jere Quinn (COA) Rick Byrd (COA) Bob Huggins (COA) Lamont Robinson (PLA) Muggsy Bogues (PLA) Mark Jackson (PLA) Bo Ryan (COA) Irv Brown (REF) Herman Johnson (COA) Bob Saulsbury (COA) Jim Burch (REF) Marques Johnson (PLA) Norm Sloan (COA) Marcus Camby (PLA) George Karl (COA) Ben Wallace (PLA) Michael Cooper (PLA)* Gene Keady (COA) Chris Webber (PLA) Jack Curran (COA) Ken Kern (COA) Willie West (COA) Mark Eaton (PLA) Shawn Marion (PLA) Buck Williams (PLA) Cliff Ellis (COA) Rollie Massimino (COA) Jay Wright (COA) Dale Ellis (PLA) Bob McKillop (COA) Paul Westhead (COA)* Hugh Evans (REF) Danny Miles (COA) Michael Finley (PLA) Steve Moore (COA) Women’s Committee Nominations Leta Andrews (COA) Becky Hammon (PLA) Kim Mulkey (PLA) Jennifer Azzi (PLA) Lauren Jackson (PLA)* Marianne Stanley (COA) Swin Cash (PLA) Suzie McConnell (PLA) Valerie Still (PLA) Yolanda Griffith (PLA)* Debbie Miller-Palmore (PLA) Marian Washington (COA) DIRECT-ELECT CATEGORY: Contributor Committee Nominations Val Ackerman* Simon Gourdine Jerry McHale Marv -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Letter to collector and introduction to catalog ........................................................................................ 4 Auction Rules ............................................................................................................................................... 5 Clean Sweep All Sports Affordable Autograph/Memorabilia Auction Day One Wednesday December 11 Lots 1 - 804 Baseball Autographs ..................................................................................................................................... 6-43 Signed Cards ................................................................................................................................................... 6-9 Signed Photos.................................................................................................................................. 11-13, 24-31 Signed Cachets ............................................................................................................................................ 13-15 Signed Documents ..................................................................................................................................... 15-17 Signed 3x5s & Related ................................................................................................................................ 18-21 Signed Yearbooks & Programs ................................................................................................................. 21-23 Single Signed Baseballs ............................................................................................................................ -

2017 Enshrinement Program

Title goes here 2017 Enshrinement Ceremony Presented by November 8, 2017 Sawgrass Marriott Golf Resort & Spa | Ponte Vedra, Florida YOUR VACATION IN THE M ddle SoTAfR TESV HeERrEywhere Want to squeeze more play out of your Florida getaway? Stay in Central Florida’s Polk County. Home to LEGOLAND® Florida Resort, 554 sparkling lakes and outstanding outdoor recreation, this is the affordable and opportunity-rich paradise you’ve been searching for. And with Tampa and Orlando less than an hour away, you can add white-sand beaches, heart-racing roller coasters and the most magical place on earth to your “must-do” list—because when your dollar goes further, so can you. Your wallet-wise vacation starts at VisitCentralFlorida.com CHoose in 800-828-7655 Very†hing twitter.com/VisitCentralFL E facebook.com/VisitCentralFlorida at the Central Florida Visitor Information Center 101 Adventure Ct., Davenport, FL 33837 Barry Smith Letter from the President ATION IN THE YOUR VAC On behalf of our 249 members, executive director Wayne ARTS HeErREywhere Hogan and our Board of Directors from across the state, T EV I want to personally welcome you to the 56th annual Florida Sof dle Sports Hall of Fame Induction Ceremonies presented by d FANATICS. Tonight we are honoring perhaps the most talented, M accomplished and eclectic classes in our history. The on-the-field and front-office accomplishments of this class speak volumes as we pay tribute to a Heisman Trophy winner, an NFL All-Pro and College All-American, a major golf winner, a Major League Baseball MVP and future first ballot Hall of Famer and a Commissioner who took his sport to new levels of popularity. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. IDgher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & HoweU Information Compaiy 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 OUTSIDE THE LINES: THE AFRICAN AMERICAN STRUGGLE TO PARTICIPATE IN PROFESSIONAL FOOTBALL, 1904-1962 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State U niversity By Charles Kenyatta Ross, B.A., M.A. -

Baseball News Clippings

! BASEBALL I I I NEWS CLIPPINGS I I I I I I I I I I I I I BASE-BALL I FIRST SAME PLAYED IN ELYSIAN FIELDS. I HDBOKEN, N. JT JUNE ^9f }R4$.* I DERIVED FROM GREEKS. I Baseball had its antecedents In a,ball throw- Ing game In ancient Greece where a statue was ereoted to Aristonious for his proficiency in the game. The English , I were the first to invent a ball game in which runs were scored and the winner decided by the larger number of runs. Cricket might have been the national sport in the United States if Gen, Abner Doubleday had not Invented the game of I baseball. In spite of the above statement it is*said that I Cartwright was the Johnny Appleseed of baseball, During the Winter of 1845-1846 he drew up the first known set of rules, as we know baseball today. On June 19, 1846, at I Hoboken, he staged (and played in) a game between the Knicker- bockers and the New Y-ork team. It was the first. nine-inning game. It was the first game with organized sides of nine men each. It was the first game to have a box score. It was the I first time that baseball was played on a square with 90-feet between bases. Cartwright did all those things. I In 1842 the Knickerbocker Baseball Club was the first of its kind to organize in New Xbrk, For three years, the Knickerbockers played among themselves, but by 1845 they I had developed a club team and were ready to meet all comers. -

Miscellaneous

MISCELLANEOUS Phoenix Municipal Stadium, the A’s Spring Training home OAKLAND-ALAMEDA COUNTY COLISEUM FRONT OFFICE 2009 ATHLETICS REVIEW The Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum plays host to concerts, conventions and other large gatherings in addi- tion to serving as the home for the Oakland Athletics and Oakland Raiders. The A’s have used the facility to its advantage over the years, posting the second best home record (492-318, .607) in the Major Leagues over the last 10 seasons. In 2003, the A’s set an Oakland record for home wins as they finished with a 57-24 (.704) record in the Coliseum, marking the most home wins in franchise history since 1931 RECORDS when the Philadelphia Athletics went 60-15 at home. In addition, two of the A’s World Championships have been clinched on the Coliseum’s turf. The Coliseum’s exceptional sight lines, fine weather and sizable staging areas have all contributed to its popularity among performers, promoters and the Bay Area public. The facility is conveniently located adjacent to I-880 with two exits (Hegenberger Road/66th Avenue) leading directly to the complex. Along with the Oracle Arena, which is located adjacently, it is the only major entertainment facility with a dedicated stop on the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) system. The Oakland International Airport is less than a two-mile drive from the Coliseum with shuttle service to several local hotels and restaurants. In October of 1995, the Coliseum HISTORY began a one-year, $120 renovation proj- ect that added 22,000 new seats, 90 luxury suites, two private clubs and two OAKLAND-ALAMEDA COUNTY COLISEUM state-of-the-art scoreboards.