Delhi Metro and the Making of World-Class Delhi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

India 2020 in Review

The impact of COVID-19 on older persons in India 2020 in review Highlights • India reported its first COVID-19 case on 30 January 2020 and its first COVID-19 death on 13 March 2020.1 As on 08 December 2020 India has the second highest number of reported cases of COVID-19 in the world and the third highest number of deaths due to COVID-19 globally.2 However, in terms of per capita mortality rate India is only 78th globally with 9.43 deaths per 100,000 population.3 • The Government of India (GoI) announced a countrywide lockdown from 25 March – 31 May 2020, after which restrictions were eased in a phased manner.4 • As per estimates on 13 October 2020 53 per cent of the deaths have occurred in the age group of 60 and above,5 though they accounted for only 12 per cent of COVID-19 positive cases as per data released in September.6 • A nation-wide survey of older persons in June 2020 indicated that the pandemic has adversely impacted the livelihoods of roughly 65 per cent of the participants. • An independent survey conducted in April 2020 concluded that 51 per cent of older persons surveyed were reported to have been physically or mentally mistreated during the pandemic.7 • India’s real GDP growth rate is expected to decline from 4.2 per cent in 2019 to –10.3 per cent in 2020.8 Data released by the National Statistical Office indicates that India has technically entered a recession, with the GDP of India declining by 7.5 per cent in the July- September quarter (Q2),9 following 23.9 per cent in the April-June quarter (Q1).10 • It is estimated that 400 million workers from India’s informal sector (of which 11 million are expected to be older persons) are likely to be pushed into extreme poverty.11 12 • The COVID-19 lockdown has impacted the livelihoods of a large proportion of the country’s nearly 40 million internal migrants.13 A majority of these migrant workers are daily wage labourers, who were stranded after the lockdown and started fleeing from cities to their native places. -

Government Advertising As an Indicator of Media Bias in India

Sciences Po Paris Government Advertising as an Indicator of Media Bias in India by Prateek Sibal A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the degree of Master in Public Policy under the guidance of Prof. Julia Cage Department of Economics May 2018 Declaration of Authorship I, Prateek Sibal, declare that this thesis titled, 'Government Advertising as an Indicator of Media Bias in India' and the work presented in it are my own. I confirm that: This work was done wholly or mainly while in candidature for Masters in Public Policy at Sciences Po, Paris. Where I have consulted the published work of others, this is always clearly attributed. Where I have quoted from the work of others, the source is always given. With the exception of such quotations, this thesis is entirely my own work. I have acknowledged all main sources of help. Signed: Date: iii Abstract by Prateek Sibal School of Public Affairs Sciences Po Paris Freedom of the press is inextricably linked to the economics of news media busi- ness. Many media organizations rely on advertisements as their main source of revenue, making them vulnerable to interference from advertisers. In India, the Government is a major advertiser in newspapers. Interviews with journalists sug- gest that governments in India actively interfere in working of the press, through both economic blackmail and misuse of regulation. However, it is difficult to gauge the media bias that results due to government pressure. This paper determines a newspaper's bias based on the change in advertising spend share per newspa- per before and after 2014 general election. -

Coronajihad: COVID-19, Misinformation, and Anti-Muslim Violence in India

#CoronaJihad COVID-19, Misinformation, and Anti-Muslim Violence in India Shweta Desai and Amarnath Amarasingam Abstract About the authors On March 25th, India imposed one of the largest Shweta Desai is an independent researcher and lockdowns in history, confining its 1.3 billion journalist based between India and France. She is citizens for over a month to contain the spread of interested in terrorism, jihadism, religious extremism the novel coronavirus (COVID-19). By the end of and armed conflicts. the first week of the lockdown, starting March 29th reports started to emerge that there was a common Amarnath Amarasingam is an Assistant Professor in link among a large number of the new cases the School of Religion at Queen’s University in Ontario, detected in different parts of the country: many had Canada. He is also a Senior Research Fellow at the attended a large religious gathering of Muslims in Institute for Strategic Dialogue, an Associate Fellow at Delhi. In no time, Hindu nationalist groups began to the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation, see the virus not as an entity spreading organically and an Associate Fellow at the Global Network on throughout India, but as a sinister plot by Indian Extremism and Technology. His research interests Muslims to purposefully infect the population. This are in radicalization, terrorism, diaspora politics, post- report tracks anti-Muslim rhetoric and violence in war reconstruction, and the sociology of religion. He India related to COVID-19, as well as the ongoing is the author of Pain, Pride, and Politics: Sri Lankan impact on social cohesion in the country. -

“Everyone Has Been Silenced”; Police

EVERYONE HAS BEEN SILENCED Police Excesses Against Anti-CAA Protesters In Uttar Pradesh, And The Post-violence Reprisal Citizens Against Hate Citizens against Hate (CAH) is a Delhi-based collective of individuals and groups committed to a democratic, secular and caring India. It is an open collective, with members drawn from a wide range of backgrounds who are concerned about the growing hold of exclusionary tendencies in society, and the weakening of rule of law and justice institutions. CAH was formed in 2017, in response to the rising trend of hate mobilisation and crimes, specifically the surge in cases of lynching and vigilante violence, to document violations, provide victim support and engage with institutions for improved justice and policy reforms. From 2018, CAH has also been working with those affected by NRC process in Assam, documenting exclusions, building local networks, and providing practical help to victims in making claims to rights. Throughout, we have also worked on other forms of violations – hate speech, sexual violence and state violence, among others in Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, Rajasthan, Bihar and beyond. Our approach to addressing the justice challenge facing particularly vulnerable communities is through research, outreach and advocacy; and to provide practical help to survivors in their struggles, also nurturing them to become agents of change. This citizens’ report on police excesses against anti-CAA protesters in Uttar Pradesh is the joint effort of a team of CAH made up of human rights experts, defenders and lawyers. Members of the research, writing and advocacy team included (in alphabetical order) Abhimanyu Suresh, Adeela Firdous, Aiman Khan, Anshu Kapoor, Devika Prasad, Fawaz Shaheen, Ghazala Jamil, Mohammad Ghufran, Guneet Ahuja, Mangla Verma, Misbah Reshi, Nidhi Suresh, Parijata Banerjee, Rehan Khan, Sajjad Hassan, Salim Ansari, Sharib Ali, Sneha Chandna, Talha Rahman and Vipul Kumar. -

Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha

` jIvNmu´anNdlhrI Jeevan-muktaananda-lahari (Waves of Delight of One Liberated while alive) Translated by Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha jIvNmu´anNdlhrI Jeevan-muktaananda-lahari (Waves of Delight of One Liberated while alive) Translated by Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha Narayanashrama Tapovanam Jeevan-muktaananda-lahari Author: Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha Published by: © Managing Trustee Narayanashrama Tapovanam Venginissery, P.O. Ammadam Thrissur, Kerala - 680 563 India Website: http://www.swamibhoomanandatirtha.org e-Reprint: Dec 2011 All rights are reserved. No part of this publication may be used, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, distributed or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher. Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha, a knower of the Supreme Truth, has guided numerous seekers towards the invaluable goal of Self-realization, transforming their lives into one of joy and contentment. Swamiji's interpretation of Bhagavadgeeta, Sreemad Bhaagavatam, Upanishads and other spiritual texts, coming from his experiential depth and mastery of Self-realization, inspires seekers with the liberating touch of the transcendental knowledge. Receiving deeksha (spiritual initiation) from Baba Gangadhara Paramahamsa of Dakshinkhanda, West Bengal, Swamiji embraced sannyaasa at the age of 23. Dedicating his life for the welfare of mankind, he has been relentlessly disseminating spiritual wisdom of Vedanta for over 50 years, with rare clarity, practicality and openness, to seekers all over the world. In his mission to reveal to people that "there is a way of living in this world without being bound or troubled by it," Swamiji has been travelling throughout the world like a moving university. -

Hindu Mahasabha to Organise 'Gaumutra Party'

Home / National / Hindu Mahasabha to organise 'gaumutra party' to fight coronavirus in India: Report The Mahasabha president Chakrapani Maharaj said a ‘gaumutra party’ on the lines of tea parties will be held DH Web Desk, MAR 04 2020, 19:41PM IST UPDATED: MAR 05 2020, 03:24AM IST Representative image (DH Photo) While the world is looking for ways and means to control the spread of the novel coronavirus, the Hindu Mahasabha has now popped up a new idea to contain the disease. Coronaviru… Total Confirmed 109.835 Confirmed Cases by Country/Regi on 80.699 Ma The Mahasabha president Chakrapani Maharaj said a ‘gaumutra party’ on the lines of tea parties will be held, according to a report by ThePrint. “Just like we organise tea parties, we have decided to organise a gaumutra party, wherein we will inform people about what is coronavirus and how, by consuming cow-related products, people can be saved from it,” Maharaj told the online news channel. Follow DH live coverage of coronavirus here “The event will have counters that will provide gaumutra for people to consume. At the same time, we will also put cow products like cow-dung cakes and agarbatti made from that. Upon using these, the virus will die immediately.” The Mahasabha president further told ThePrint that a big event will be organised in Delhi just past Holi to raise awareness among people as they believe the killing of animals was the cause of the spread of the disease. “We want to create awareness about jeev hatya (killing of beings), which is the main cause of coronavirus. -

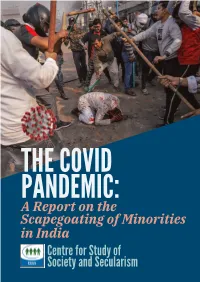

THE COVID PANDEMIC: a Report on the Scapegoating of Minorities in India Centre for Study of Society and Secularism I

THE COVID PANDEMIC: A Report on the Scapegoating of Minorities in India Centre for Study of Society and Secularism i The Covid Pandemic: A Report on the Scapegoating of Minorities in India Centre for Study of Society and Secularism Mumbai ii Published and circulated as a digital copy in April 2021 © Centre for Study of Society and Secularism All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including, printing, photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher and without prominently acknowledging the publisher. Centre for Study of Society and Secularism, 603, New Silver Star, Prabhat Colony Road, Santacruz (East), Mumbai, India Tel: +91 9987853173 Email: [email protected] Website: www.csss-isla.com Cover Photo Credits: Danish Siddiqui/Reuters iii Preface Covid -19 pandemic shook the entire world, particularly from the last week of March 2020. The pandemic nearly brought the world to a standstill. Those of us who lived during the pandemic witnessed unknown times. The fear of getting infected of a very contagious disease that could even cause death was writ large on people’s faces. People were confined to their homes. They stepped out only when absolutely necessary, e.g. to buy provisions or to access medical services; or if they were serving in essential services like hospitals, security and police, etc. Economic activities were down to minimum. Means of public transportation were halted, all educational institutions, industries and work establishments were closed. -

Hindutva Watch

UNDERCOVER Ashish Khetan is a journalist and a lawyer. In a fifteen-year career as a journalist, he broke several important news stories and wrote over 2,000 investigative and explanatory articles. In 2014, he ran for parliament from the New Delhi Constituency. Between 2015 and 2018, he headed the top think tank of the Delhi government. He now practises law in Mumbai, where he lives with his family. First published by Context, an imprint of Westland Publications Private Limited, in 2020 1st Floor, A Block, East Wing, Plot No. 40, SP Infocity, Dr MGR Salai, Perungudi, Kandanchavadi, Chennai 600096 Context, the Context logo, Westland and the Westland logo are the trademarks of Westland Publications Private Limited, or its affiliates. Copyright © Ashish Khetan, 2020 ISBN: 9789389152517 The views and opinions expressed in this work are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by him, and the publisher is in no way liable for the same. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher. For Zoe, Tiya, Dani and Chris Contents Epigraph Preface Introduction 1 A Sting in the Tale 2 Theatre of Masculinity 3 The Ten-foot-tall Officer 4 Painting with Fire 5 Alone in the Dark 6 Truth on Trial 7 Conspirators and Rioters 8 The Gulbarg Massacre 9 The Killing Fields 10 The Salient Feature of a Genocidal Ideology 11 The Artful Faker 12 The Smoking Gun 13 Drum Rolls of an Impending Massacre 14 The Godhra Conundrum 15 Tendulkar’s 100 vs Amit Shah’s 267 16 Walk Alone Epilogue: Riot after Riot Notes Acknowledgements The Big Nurse is able to set the wall clock at whatever speed she wants by just turning one of those dials in the steel door; she takes a notion to hurry things up, she turns the speed up, and those hands whip around that disk like spokes in a wheel. -

Research Update (July-Dec 2020)

Azim Premji University Research Update (July-Dec 2020) 1 Note from the Research Centre 2020 has been one of the most difficult of years. It was listed by the UN as the “International Year of Plant Health” and by the World Health Organization as the “Year of the Nurse and Midwife”. Sadly, the main thing the year will be remembered for is the COVID-19 Pandemic. As the year draws to an end, it is time for us to look forth with hope and expectation to a very different 2021. For the past two years, Azim Premji University has brought out a newsletter at regular intervals, to keep us updated on the research we collectively conduct. What started as a simple exercise of collation became more than a summary, as we experimented with different sections, and added new formats. As 2020 draws to a close, we have changed the format to a ‘magazine-like’ version. In this issue, you will find the regular newsletter coverage of articles, journal papers, research, etc. In addition, you will also find a new thematic focus: with some crystal ball-gazing into the future, we collectively engage in “Heralding 2021”. We have tried to make it as readable and visually rich as possible. As said earlier, we are evolving with time, and if you have any comments to share on the content, format or look n feel, do drop us a mail on [email protected] In the end, as we ring in the new year – 2021, declared as the “International Year of Peace and Trust,” and “the International Year of Creative Economy for Sustainable Development” by the UN, one can only hope and pray that it does not get stamped by one label or defined by one trend. -

December 2020 Page 1

DECEMBER 2020 PAGE 1 Globally Recognized Editor-in-Chief: Azeem A. Quadeer, M.S., P.E. DECEMBER 2020 Vol 11, Issue12 Release Ahmed Patel Guantanamo dies at 70 Prisoners Page 11 The oldest prisoner at the Guantanamo Bay detention center went to his latest review board hearing with a GHMC degree of hope, something that has been scarce dur- Elections ing his 16 years locked up without charges at the U.S. P-38 base in Cuba. Saifullah Paracha, a 73-year-old Pakistani P - 20 with diabetes and a heart condition, had two things going for him that he didn’t have at previous hearings: a favorable legal develop- ment and the election of Joe The Correct Way to Biden. Deal with President Donald Trump had effectively ended the Blasphemy P-6 Obama administration’s practice of reviewing the cases of men held at Guan- tanamo and releasing them if imprisonment was no longer deemed necessary. Coolie No. 1 Now there’s hope that will P-40 resume under Biden. HYDERABAD I am more hopeful now simply because we have an Maradona - the administration to look for- lengend passes FLAT FOR SALE ward to that isnt dead set on ignoring the existing review away process,” Paracha’s attorney, P-15 SAARA HOMES Shelby Sullivan-Bennis, said by phone from the base on RING ROAD Nov. 19 after the hearing. The simple existence of that PILLAR #174 on the horizon I think is hope for all of us.” 3BR 2BA 1010 SFT Guantanamo was once a source of global outrage and 29 LAKHS a symbol of U.S. -

Be What You Are

Be What You Are Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha Be What You Are Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha Narayanashrama Tapovanam www.swamibhoomanandatirtha.org Be What You Are Author: Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha Published by © Managing Trustee Narayanashrama Tapovanam Venginissery, Paralam, P.O. Paralam Thrissur, Kerala 680 563, INDIA Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.swamibhoomanandatirtha.org First Edition 1991 eBook Reprint Jun 2013 All rights are reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher. Foreword The association we seek, in ignorance, with worldly minded people leads to bondage. But the same association, if cultivated with holy men, leads to non- attachment .... [Srimad Bhaagavatam, Canto 3, Chapter 23, Shloka 55] A distinct urge to seek clear and correct answers to genuine questions is an indication that a person is now ready to tread the path of seeking and eventual fulfillment. The only requirement is that the seeker must develop genuine sraddha (attention) to find answers and do sadhana regularly. In our age-old Guru-sishya parampara (teacher- student tradition), involved in the ancient Gurukula mode of imparting spiritual wisdom, it is enjoined on the students to approach the Guru with utmost humility and earnestness. The Gita says: “With reverential salutations do you approach them- the wise men who have known the Truth. Serve them, and enquire from them with due respect, until your doubts are clarified. These wise men will impart the knowledge of this divine Truth to you.” (Chapter 4, sloka 34).