Iguana Iguanaenglishbrianbockedited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cyclura Or Rock Iguanas Cyclura Spp

Cyclura or Rock Iguanas Cyclura spp. There are 8 species and 16 subspecies of Cyclura that are thought to exist today. All Cyclura species are endangered and are listed as CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) Appendix I, the highest level of pro- tection the Convention gives. Wild Cyclura are only found in the Caribbean, with many subspecies endemic to only one particular island in the West Indies. Cyclura mature and grow slowly compared to other lizards in the family Iguani- dae, and have a very long life span (sometimes reaches ages of 50+ years). The more common species in the pet trade in- clude the Rhinoceros Iguana (Cyclura cornuta cornuta), and Cuban Rock Iguana (juvenile), the Cuban Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila nubila). Cyclura nubila nubila Basic Care: Habitat: Cyclura care is similar to that of the Green Iguana (Iguana iguana), but there are some major differences. Cyclura Iguanas are generally ground-dwelling lizards, and require a very large cage with lots of floor space. The suggested minimum space to keep one or two adult Cyclura in captivity is usually a cage that is at the very least 10’X10’. Because of this space requirement, many cyclura owners choose to simply des- ignate a room of their home to free-roaming. If a male/female pair are to be kept to- gether, multiple basking spots, feeding stations, and hides will be required. All Cyclura are extremely territorial and can inflict serious injuries or even death to their cage- mates unless monitored carefully. The recommended temperature for Cyclura is a basking spot of about 95-100F during the day, with a temperature gradient of cooler areas to escape the heat. -

Xenosaurus Tzacualtipantecus. the Zacualtipán Knob-Scaled Lizard Is Endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of Eastern Mexico

Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus. The Zacualtipán knob-scaled lizard is endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of eastern Mexico. This medium-large lizard (female holotype measures 188 mm in total length) is known only from the vicinity of the type locality in eastern Hidalgo, at an elevation of 1,900 m in pine-oak forest, and a nearby locality at 2,000 m in northern Veracruz (Woolrich- Piña and Smith 2012). Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus is thought to belong to the northern clade of the genus, which also contains X. newmanorum and X. platyceps (Bhullar 2011). As with its congeners, X. tzacualtipantecus is an inhabitant of crevices in limestone rocks. This species consumes beetles and lepidopteran larvae and gives birth to living young. The habitat of this lizard in the vicinity of the type locality is being deforested, and people in nearby towns have created an open garbage dump in this area. We determined its EVS as 17, in the middle of the high vulnerability category (see text for explanation), and its status by the IUCN and SEMAR- NAT presently are undetermined. This newly described endemic species is one of nine known species in the monogeneric family Xenosauridae, which is endemic to northern Mesoamerica (Mexico from Tamaulipas to Chiapas and into the montane portions of Alta Verapaz, Guatemala). All but one of these nine species is endemic to Mexico. Photo by Christian Berriozabal-Islas. amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 01 June 2013 | Volume 7 | Number 1 | e61 Copyright: © 2013 Wilson et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Com- mons Attribution–NonCommercial–NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License, which permits unrestricted use for non-com- Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 7(1): 1–47. -

West Indian Iguana Husbandry Manual

1 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 4 Natural history ............................................................................................................................... 7 Captive management ................................................................................................................... 25 Population management .............................................................................................................. 25 Quarantine ............................................................................................................................... 26 Housing..................................................................................................................................... 26 Proper animal capture, restraint, and handling ...................................................................... 32 Reproduction and nesting ........................................................................................................ 34 Hatchling care .......................................................................................................................... 40 Record keeping ........................................................................................................................ 42 Husbandry protocol for the Lesser Antillean iguana (Iguana delicatissima)................................. 43 Nutrition ...................................................................................................................................... -

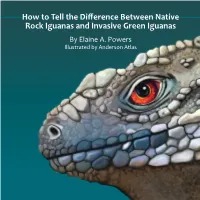

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas by Elaine A

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas By Elaine A. Powers Illustrated by Anderson Atlas Many of the islands in the Caribbean Sea, known as the West Rock Iguanas (Cyclura) Indies, have native iguanas. B Cuban Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila), Cuba They are called Rock Iguanas. C Sister Isles Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila caymanensis), Cayman Brac and Invasive Green Iguanas have been introduced on these islands and Little Cayman are a threat to the Rock Iguanas. They compete for food, territory D Grand Cayman Blue Iguana (Cyclura lewisi), Grand Cayman and nesting areas. E Jamaican Rock Iguana (Cyclura collei), Jamaica This booklet is designed to help you identify the native Rock F Turks & Caicos Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata), Turks and Caicos. Iguanas from the invasive Greens. G Booby Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata bartschi), Booby Cay, Bahamas H Andros Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura), Andros, Bahamas West Indies I Exuma Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura figginsi), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Exumas BAHAMAS J Allen’s Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura inornata), Exuma Islands, J Islands Bahamas M San Salvador Andros Island H Booby Cay K Anegada Iguana (Cyclura pinguis), British Virgin Islands Allens Cay White G I Cay Ricord’s Iguana (Cyclura ricordi), Hispaniola O F Turks & Caicos L CUBA NAcklins Island M San Salvador Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi), San Salvador, Bahamas Anegada HISPANIOLA CAYMAN ISLANDS K N Acklins Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi nuchalis), Acklins Islands, Bahamas B PUERTO RICO O White Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi cristata), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Grand Cayman D C JAMAICA BRITISH P Rhinoceros Iguana (Cyclura cornuta), Hispanola Cayman Brac & VIRGIN Little Cayman E L P Q Mona ISLANDS Q Mona Island Iguana (Cyclura stegnegeri), Mona Island, Puerto Rico Island 2 3 When you see an iguana, ask: What kind do I see? Do you see a big face scale, as round as can be? What species is that iguana in front of me? It’s below the ear, that’s where it will be. -

Suggested Guidelines for Reptiles and Amphibians Used in Outreach

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR REPTILES AND AMPHIBIANS USED IN OUTREACH PROGRAMS Compiled by Diane Barber, Fort Worth Zoo Originally posted September 2003; updated February 2008 INTRODUCTION This document has been created by the AZA Reptile and Amphibian Taxon Advisory Groups to be used as a resource to aid in the development of institutional outreach programs. Within this document are lists of species that are commonly used in reptile and amphibian outreach programs. With over 12,700 species of reptiles and amphibians in existence today, it is obvious that there are numerous combinations of species that could be safely used in outreach programs. It is not the intent of these Taxon Advisory Groups to produce an all-inclusive or restrictive list of species to be used in outreach. Rather, these lists are intended for use as a resource and are some of the more common species that have been safely used in outreach programs. A few species listed as potential outreach animals have been earmarked as controversial by TAG members for various reasons. In each case, we have made an effort to explain debatable issues, enabling staff members to make informed decisions as to whether or not each animal is appropriate for their situation and the messages they wish to convey. It is hoped that during the species selection process for outreach programs, educators, collection managers, and other zoo staff work together, using TAG Outreach Guidelines, TAG Regional Collection Plans, and Institutional Collection Plans as tools. It is well understood that space in zoos is limited and it is important that outreach animals are included in institutional collection plans and incorporated into conservation programs when feasible. -

Bibliography and Scientific Name Index to Amphibians

lb BIBLIOGRAPHY AND SCIENTIFIC NAME INDEX TO AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES IN THE PUBLICATIONS OF THE BIOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF WASHINGTON BULLETIN 1-8, 1918-1988 AND PROCEEDINGS 1-100, 1882-1987 fi pp ERNEST A. LINER Houma, Louisiana SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE NO. 92 1992 SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE The SHIS series publishes and distributes translations, bibliographies, indices, and similar items judged useful to individuals interested in the biology of amphibians and reptiles, but unlikely to be published in the normal technical journals. Single copies are distributed free to interested individuals. Libraries, herpetological associations, and research laboratories are invited to exchange their publications with the Division of Amphibians and Reptiles. We wish to encourage individuals to share their bibliographies, translations, etc. with other herpetologists through the SHIS series. If you have such items please contact George Zug for instructions on preparation and submission. Contributors receive 50 free copies. Please address all requests for copies and inquiries to George Zug, Division of Amphibians and Reptiles, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC 20560 USA. Please include a self-addressed mailing label with requests. INTRODUCTION The present alphabetical listing by author (s) covers all papers bearing on herpetology that have appeared in Volume 1-100, 1882-1987, of the Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington and the four numbers of the Bulletin series concerning reference to amphibians and reptiles. From Volume 1 through 82 (in part) , the articles were issued as separates with only the volume number, page numbers and year printed on each. Articles in Volume 82 (in part) through 89 were issued with volume number, article number, page numbers and year. -

CARE of the GREEN IGUANA

Client Education—Green Iguana CARE of the GREEN IGUANA Iguanas in the Wild The green or common iguana (Iguana iguana) is a tree-dwelling reptile native to the tropical and subtropical regions of central and South America and parts of Mexico. The iguana is a solitary creature. Soon after hatching, the young go off to live alone. Iguanas come together only during the breeding season. The green iguana is a strict vegetarian, feeding primarily on vines, stems, leaves and flowers. The iguana also has a good sense of sight, smell and hearing. It tends to be a wary creature and will hide or flee at the first sign of danger. During the day, iguanas bask on tree branches that hang over the water. When threatened or frightened, the iguana will drop into the water or the ground below. Keeping a Pet Iguana Unlike domestic pets that have lived with human beings for multiple generations, pet reptiles, (even those that are captive bred) are still essentially wild animals. Our goal for keeping iguanas in captivity should be to copy their natural environment and diet as closely as possible. With proper care, iguanas can live for up to 12 to 15 years and reach six feet in length. Your Iguana’s Environment Iguanas are asocial, territorial animals and should be housed singularly. Young iguanas may seem to coexist well at first, but problems soon arise since the larger, more aggressive iguana will physically intimidate its cage mates and monopolize food and heat sources. Iguanas, particularly those less than 2 years of age, should be confined to their enclosure. -

THE ORIGIN and EVOLUTION of SNAKE EYES Dissertation

CONQUERING THE COLD SHUDDER: THE ORIGIN AND EVOLUTION OF SNAKE EYES Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment for the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Christopher L. Caprette, B.S., M.S. **** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Thomas E. Hetherington, Advisor Approved by Jerry F. Downhower David L. Stetson Advisor The graduate program in Evolution, John W. Wenzel Ecology, and Organismal Biology ABSTRACT I investigated the ecological origin and diversity of snakes by examining one complex structure, the eye. First, using light and transmission electron microscopy, I contrasted the anatomy of the eyes of diurnal northern pine snakes and nocturnal brown treesnakes. While brown treesnakes have eyes of similar size for their snout-vent length as northern pine snakes, their lenses are an average of 27% larger (Mann-Whitney U test, p = 0.042). Based upon the differences in the size and position of the lens relative to the retina in these two species, I estimate that the image projected will be smaller and brighter for brown treesnakes. Northern pine snakes have a simplex, all-cone retina, in keeping with a primarily diurnal animal, while brown treesnake retinas have mostly rods with a few, scattered cones. I found microdroplets in the cone ellipsoids of northern pine snakes. In pine snakes, these droplets act as light guides. I also found microdroplets in brown treesnake rods, although these were less densely distributed and their function is unknown. Based upon the density of photoreceptors and neural layers in their retinas, and the predicted image size, brown treesnakes probably have the same visual acuity under nocturnal conditions that northern pine snakes experience under diurnal conditions. -

Iguanas in Florida N Green and Spinytail Iguanas Are Native to Central and South America, but Are Commonly Found in the Exotic Pet Trade

Iguana fast facts n Iguanas are large lizards that can grow over 4 feet in length. Iguanas in Florida n Green and spinytail iguanas are native to Central and South America, but are commonly found in the exotic pet trade. n Iguanas bask in open areas and are often seen on sidewalks, docks, patios, decks, in trees or open mowed areas. n They can run or climb swiftly when frightened and dive into water or retreat into burrows or thick foliage. n Green iguanas can range from green to Black spinytail iguana, Adam G. Stern grayish black in color and have a row of spikes down the center of the head and back. n During the breeding season, adult male green iguanas can sometimes take on an orange hue. n Spinytail iguanas can range from gray to dark tan in color with black bands and have whorls of spiny scales on the tail. n Green iguanas are mainly herbivores and feed primarily on leaves, flowers and fruits of Mexican spinytail iguana, Kenneth L. Krysko various broad-leaved herbs, shrubs and trees, but will feed on other items opportunistically. If you have further questions or need more n Spinytail iguanas are omnivorous, eating help, call your regional Florida Fish and primarily vegetation, but have been Wildlife Conservation Commission office: documented eating small animals and eggs. Three members of the iguana family are now established in South Florida and occasionally observed in other parts of Florida: the green Main Headquarters iguana, the Mexican spinytail iguana, and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission black spinytail iguana. -

RHINOCEROS IGUANA Cyclura Cornuta Cornuta (Bonnaterre 1789)

HUSBANDRY GUIDELINES: RHINOCEROS IGUANA Cyclura cornuta cornuta (Bonnaterre 1789) REPTILIA: IGUANIDAE Compiler: Cameron Candy Date of Preparation: DECEMBER, 2009 Institute: Western Sydney Institute of TAFE, Richmond, NSW, Australia Course Name/Number: Certificate III in Captive Animals - 1068 Lecturers: Graeme Phipps - Jackie Salkeld - Brad Walker Husbandry Guidelines: C. c. cornuta 1 ©2009 Cameron Candy OHS WARNING RHINOCEROS IGUANA Cyclura c. cornuta RISK CLASSIFICATION: INNOCUOUS NOTE: Adult C. c. cornuta can be reclassified as a relatively HAZARDOUS species on an individual basis. This may include breeding or territorial animals. POTENTIAL PHYSICAL HAZARDS: Bites, scratches, tail-whips: Rhinoceros Iguanas will defend themselves when threatened using bites, scratches and whipping with the tail. Generally innocuous, however, bites from adults can be severe resulting in deep lacerations. RISK MANAGEMENT: To reduce the risk of injury from these lizards the following steps should be followed: - Keep animal away from face and eyes at all times - Use of correct PPE such as thick gloves and employing correct and safe handling techniques when close contact is required. Conditioning animals to handling is also generally beneficial. - Collection Management; If breeding is not desired institutions can house all female or all male groups to reduce aggression - If aggressive animals are maintained protective instrument such as a broom can be used to deflect an attack OTHER HAZARDS: Zoonosis: Rhinoceros Iguanas can potentially carry the bacteria Salmonella on the surface of the skin. It can be passed to humans through contact with infected faeces or from scratches. Infection is most likely to occur when cleaning the enclosure. RISK MANAGEMENT: To reduce the risk of infection from these lizards the following steps should be followed: - ALWAYS wash hands with an antiseptic solution and maintain the highest standards of hygiene - It is also advisable that Tetanus vaccination is up to date in the event of a severe bite or scratch Husbandry Guidelines: C. -

NAME: Land Iguana and Marine Iguana – Both in the Family Iguanidae CLASSIFICATION: Land: Ge- Nus Conolophus; Species (Two) Su

Grab & Go NAME: Land Iguana and Marine Iguana – both in the Family Iguanidae CLASSIFICATION: Land: Ge- nus Conolophus; Species (two) subcristatus and pallidus Marine: Genus Amblyrhynchus; Species cristatus MAIN MESSAGES: The Galapagos are a quintessential example of islands as living laboratories of evolution. ✤ Beginning with Darwin and Wallace, the study of islands has provided insight into how organisms colo- nize new environments and, through successive genera- tions, undergo changes that make their descendants more suited to thrive in the new environment CAS has made research ex- peditions to the Galapagos and has been involved in conservation efforts there for over 100 years. ✤ CAS collections from the Galapagos are the best in the world. Today, the Academy continues its research in the Galapagos and maintains the best collection of Galapagos materials in the world. Scientists at CAS collect plants and animals on research expedi- tions around the world. Their work and Academy collections provide invaluable baseline information about human impacts and change over time. DISTRIBUTION AND HABITAT: All are inhabitants of the Galapagos Islands. A spiny- tailed Central American Iguana may be ancestral to all three, but the marine species evolved from the terrestrial iguanas and thus is endemic to the Galapagos. Further, it is the only sea-going iguana in the world, and spends its entire life in the intertidal/sub- tidal zones. Although the land iguanas live on several islands, they are mostly seen on Plaza Sur. More widespread, the marine iguanas are seen in the channel between Isa- bella and Fernandina and along the cliffs of Espanola. DESCRIPTION AND DIET: Marine iguanas may range from 2 to 20 lbs, usually with a blackish color. -

Carbajal Et Al 15-17 2015

REVISTA MEXICANA DE HERPETOLOGÍA VOL. 1, NO. 1 :15–17 Loxocemus bicolor (SERPENTES: LOXOCEMIDAE): ELEVATIONAL AND GEOGRAPHIC RANGE EXTENSION IN MICHOACAN, MEXICO Rubén Alonso Carbajal-Márquez1 *, Jose Carlos Arenas-Monroy2 , Marco Antonio Domínguez- De la Riva3 and Eric Abdel Rivas-Mercado3 1Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste, La Paz, Baja California Sur, 23096, México. 2Laboratorio de Herpetología, Museo de Zoología, Departamento de Biología Evolutiva, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 04510. Distrito Federal, México. 3Universidad Autónoma de Aguascalientes, Centro de Ciencias Básicas, Departamento de Biología, Aguascalientes, Aguascalientes 20131, México. *Correspondent: [email protected] Abstract.— We document the occurrence of Loxocemus bicolor in the arid tropical scrub forest at Hoyo del Aire, Municipality of Taretan, Michoacan, an adult specimen that represents a new municipality record, which increases the geographic range and elevational gradient of the species in the state. Keywords.— Mexican Burrowing Python, Taretan, Squamata. Resumen.— Se registra la presencia de Loxocemus bicolor en el bosque tropical caducifolio de Hoyo del Aire, municipio de Taretan, Michoacán; un ejemplar adulto que representa un nuevo registro municipal y que incrementa la distribución geográfica y el gradiente de altitud para la especie en el estado. Palabras clave.— Pitón de Madriguera Mexicano, Taretan, Squamata The Mexican burrowing python is the only iguana eggs (Greene 1983, Mora and species in the monotypic genus Loxocemus and Robinson 1984, Mora 1987). This is an family Loxocemidae (Uetz 2013). It lives in oviparous species, with the largest dry forests and savannas, from sea level up documented clutch of four eggs (Köhler to ~600 m, from Nayarit, Mexico to Costa 2003).