People S Participation Under MGNREGS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Champhai District, Mizoram

Technical Report Series: D No: Ground Water Information Booklet Champai District, Mizoram Central Ground Water Board North Eastern Region Ministry of Water Resources Guwahati October 2013 GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET CHAMPHAI DISTRICT, MIZORAM DISTRICT AT A GLANCE Sl. ITEMS STATISTICS No. 1. GENERAL INFORMATION i) Geographical Area (sq.km.) 3,185.8 sq km ii) Administrative Divisions (as on 2011) There are four blocks, namely; khawjawl,Khawbung,Champai and Ngopa,RD Block.. iii) Population (as per 2011 Census) 10,8,392 iv) Average Annual Rainfall (mm) 2,794mm 2. GEOMORPHOLOGY i) Major Physiographic Units Denudo Structural Hills with low and moderate ridges. ii) Major Drainages Thhipui Rivers 3. LAND USE (sq. km.) More than 50% area is covered by dense forest and the rest by open forest. Both terraced cultivation and Jhum (shifting) tillage (in which tracts are cleared by burning and sown with mixed crops) are practiced. 4. MAJOR SOIL TYPES Colluvial soil 5. AREA UNDER PRINCIPAL CROPS Fibreless ginger, paddy, maize, (sq.km.) mustard, sugarcane, sesame and potato are the other crops grown in this area. 6. IRRIGATION BY DIFFERENT SOURCES N.A (sq.km.) Other sources Small scale irrigation projects are being developed through spring development with negligible command area. 7. PREDOMINANT GEOLOGICAL Lower Tertiary Formations of FORMATIONS Oligocene and Miocene Age 8. HYDROGEOLOGY i) Major water Bearing Formations Semi consolidated formations of Tertiary rocks. Ground water occurs in the form of spring emanating through cracks/fissures/joints etc. available in the country rock. 9. GROUND WATER EXPLORATION BY CGWB (as on 31.03.09) Nil 10. -

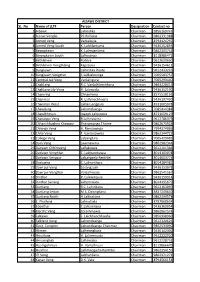

SL. No Name of LLTF Person Designation Contact No 1 Aibawk

AIZAWL DISTRICT SL. No Name of LLTF Person Designation Contact no 1 Aibawk Lalrindika Chairman 9856169747 2 Aizawl Venglai PC Ralliana Chairman 9862331988 3 Armed Veng Vanlalbula Chairman 8794424292 4 Armed Veng South K. Lalthlantuma Chairman 9436152893 5 Bawngkawn K. Lalmuankima Chairman 9862305744 6 Bawngkawn South Lalrosanga Chairman 8118986473 7 Bethlehem Rohlira Chairman 9612629630 8 Bethlehem Vengthlang Kapzauva Chairman 9436154611 9 Bungkawn Lalrindika Royte Chairman 9612433243 10 Bungkawn Vengthar C.Lalbiaknunga Chairman 7005583757 11 Centtral Jail Veng Vanlalngura Chairman 7005293440 12 Chaltlang R.C. Vanlalhlimchhana Chairman 9863228015 13 Chaltlang Lily Veng H. Lalenvela Chairman 9436152190 14 Chamring Chhanhima Chairman 8575518166 15 Chanmari R. Lalhmachhuana Chairman 9436197490 16 Chanmari West Lalliansangpuia Chairman 8731005978 17 Chawilung Lalnuntluanga Chairman 7085414388 18 Chawlhhmun Joseph Lalnunzira Chairman 8731059129 19 Chawnpui Veng R.Lalrinawma Chairman 9612786379 20 Chhanchhuahna Khawpui Thangmanga Thome Chairman 9862673924 21 Chhinga Veng H. Ramzawnga Chairman 7994374886 22 Chite Veng F. Vanlalsawma Chairman 9862344723 23 College Veng Lalsanglura Chairman 7005429082 24 Dam Veng Lawmawma Chairman 9862982344 25 Darlawn Chhimveng Lalfakzuala Chairman 9612201386 26 Darlawn Venghlun C. Lalchanmawia Chairman 8014103078 27 Darlawn Vengpui Lalsangzela Renthlei Chairman 8014603774 28 Darlawng C. Lalnunthara Chairman 8014184382 29 Dawrpui Veng Zosangzuali Chairman 9436153078 30 Dawrpui Vengthar Vanlalhruaia Chairman 9862541567 31 Dinthar R. Lalawmpuia Chairman 9436159914 32 Dinthar Sairang Lalremruata Chairman 8014195679 33 Durtlang R.C. Lalrinliana Chairman 9612163099 34 Durtlang Leitan M.S. Dawngliana Chairman 8837209640 35 Durtlang North H.Lalthakima Chairman 9862399578 36 E. Phaileng Lalruatzela Chairman 8787868634 37 Edenthar C.Lalramliana Chairman 9436360954 38 Electric Veng Zorammawia Chairman 9862867574 39 Falkawn F. Lalchhanchhuaha Chairman 9856998960 40 Falkland Veng Lalnuntluanga Chairman 9612320626 41 Govt. -

Mizoram State Roads II – Regional Transport Connectivity Project (Funded by the World Bank)

Resettlement Action Plan and Indigenous Peoples Development Plan for Champhai – Zokhawthar Road Public Disclosure Authorized Mizoram State Roads II – Regional Transport Connectivity Project (funded by The World Bank) Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized RESETTLEMENT ACTION PLAN AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES DEVELOPMENT PLAN Public Disclosure Authorized OF CHAMPHAI – ZOKHAWTHAR ROAD February 2014 Mizoram State Roads II – Regional Connectivity Project Page 1 Resettlement Action Plan and Indigenous Peoples Development Plan for Champhai – Zokhawthar Road TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................. 7 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................. 10 Chapter 1 – Project Identification ............................................................................................ 1 1.1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Existing Road Conditions ................................................................................................. 2 1.3 Salient Features of the Project Road ................................................................................. 2 Chapter 2 – Objectives and Study Methodology .................................................................... 5 2.1 Objectives ......................................................................................................................... -

Project Staff

Project Staff Thanhlupuia : Research Officer Ruth Lalrinsangi : Inspector of Statistics Lalrinawma : Inspector of Statistics Zorammawii Colney : Software i/c Lalrintluanga : Software i/c Vanlalruati : Statistical Cell Contents Page No. 1. Foreword - (i) 2. Preface - (ii) 3. Message - (iii) 4. Notification - (iv) Part-A (Abstract) 1. Dept. of School Education, Mizoram 2009-2010 at a Glance - 1 2. Number of schools by management - 2 3. Enrolment of students by management-wise - 3 4. Number of teachers by management-wise - 4 5. Abstract of Primary Schools under Educational Sub-Divisions - 5-9 6. Abstract of Middle Schools under Educational Sub-Divisions - 10-16 7. Abstract of High Schools under Educational Districts - 17-18 8. Abstract of Higher Secondary Schools under Educational Districts - 19-23 Part-B (List of Schools with number of teachers and enrolment of students) PRIMARY SCHOOLS: Aizawl District 1.SDEO, AizawlEast - 25-30 2.SDEO, AizawlSouth - 31-33 3.SDEO, AizawlWest - 34-38 4. SDEO, Darlawn - 39-41 5.SDEO, Saitual - 42-43 Champhai District 6.SDEO, Champhai - 44-47 7. SDEO, Khawzawl - 48-50 Kolasib District 8. SDEO, Kolasib - 51-53 9. SDEO, Kawnpui - 54-55 Lawngtlai District 10. EO, CADC - 56-59 11. EO, LADC - 60-64 Lunglei District 12.SDEO, LungleiNorth - 65-67 13.SDEO, LungleiSouth - 68-70 14.SDEO, Lungsen - 71-74 15. SDEO, Hnahthial - 75-76 Mamit District 16. SDEO, Mamit - 77-78 17. SDEO, Kawrthah - 79-80 18.SDEO, WestPhaileng - 81-83 Saiha District 19. EO, MADC - 84-87 Serchhip District 20. SDEO, Serchhip - 88-89 21. SDEO, North Vanlaiphai - 90 22.SDEO, Thenzawl - 91 MIDDLE SCHOOLS: Aizawl District 23.SDEO, Aizawl East - 93-97 24.SDEO, AizawlSouth - 98-99 25. -

Synfocity=573

Synod Information & Publicity Department, Synod Office (Third Floor), Mission Veng, Aizawl Synfocity = 573 th mail us at : [email protected]; [email protected] - Phone - 2314648 18 February, 2016 1 Mission Board w PCI kaltlanga CWM hnuaia thawktu kan tirh Dr. Ramdinthara Sailo te chhungkua chu CWM hnuaia an thawh hun chhung a tawp hnuah an thawhna Kohhranten thawk zui leh turin an ngen a. An ngen anga engemaw chen an thawhzui hnuah lo chhuakin, January 30, 2016 khan Mizoram an rawn thleng a,. Dr. Ramdinthara Sailo te nupa hi Synod Officers' Meeting (OM) ruahman angin John William Hospital, Lunglei-ah an thawk tawh ang. w February 19 - 21, 2016 chhunga Damparengpuia Bru Convention neih tum chu remchan zawkna avangin April 1 - 3, 2016-ah sawn a ni. w Rawngbawlnaa kan thawhpui Interserve India nen thawhhona Thuthlung (Partnership Agreement) chu kum 3 chhung (2016 - 2018) atan ziah thar a ni. 1 Finance Dept February 20, 2016 (Inrinni) khian Electric Veng Kohhranah Account Training neih a ni dawn a, Tv Zaihmingthanga, Accountant leh T/Upa David Lalnunfela O/A te an kal ang. 1 Zin w February 18, 2016 (Ningani) hian Silchar-ah Barak Area Committee neih a ni a, he mi hun hmang hian Rev. H. Lalrinmawia, Synod Moderator, Rev. Lalramliana Pachuau, Sr. Executive Secretary, Rev. B. Sangthanga, Executive Secretary, Upa H Ronghaka, Synod Secretary (Sr), Rev. K Lalrinmawia, Secretary, Synod Mission Board, Rev. H Laltlanchhunga, Rev. TC Laltlanzova, Rev. K Lalthangmawia leh Upa J Lalhlima te an kal. w February 18 - 21, 2016 chhung hian Champhai, Khuangleng leh Kelkang ah te Presbyterian English School tlawh leh programme hrang hrang hmang turin Upa DP Biakkhuma, Supervisor of Schools, Synod Office a kal ang. -

Gazette" .Jtilthority

---..,. " The Mizoram Gazette" " �- EXTRA ORDINARYJ ' .... Publi·shed by' - .JtilthoritY REGN. NO. N.E.-313 (MZ) Rs. 2/- per ISsue Vo 1. XXXVI Aizawl. Friday. 25.5.2007. Jyaistba 4, S.E. 1929, Issue No. 152 NOTIFICATION No. G. 280 14i54/2006-PLG, the 17th May, 2007. As per provision of article 243 ZD of th� Indian Constitution, the Governor of Mizoram is pleased to - constitute CHAMPHAI DISTRICT PLANNING COMMITTEE to prepare draft Developmental Plan for the District as a whole with immediate effect and until further order� ' Th� CH \.MPHAI DISTRICT PLANNING COMMITTEE shall, in preparing the draft D=velopmental Plan. ha ve regard to: Matters 1) of cC'mmon hterest including spatial planning sharing of water and other phYSical and na tural resources, tne integrated Development of infrastructure and environment conservation. II) The extent and type of available resourceS whether financial or otherwise. rganization Ill) and consult such instilutions and o as the Governor,' may, by order, specify. T�e CHA MPHAI DISTRICT PLANNING COMMITTEE shall have the fo Howi ng members: 1. Chairman D�puty Commissioner, Champhai District. � �. Secret ary Project Director, DRDA, Champhai. 3. Member Pu K. ya�lalauv� MLA, Khawbung. Constituency 4. Member Pu Vdnnhana Sallo, MLA, Kbawhal Constituency. 5. Member Pu Andr ew Laiherliana, MLA, Khawzawl r Constituency. 6. Member Pu H. �Rohluna, MLA, Ngopa Con$tituency. 7. Member Preside nt . 1\fHlP Sub. Hqrs. Champhai. 8. Member J!resident, YMA Champhai Group. Ex-152j2007 2 9. Member President, AMFU, Champhai District Hqrs. 10. Member Manager. SBI, Champhai Branch. 11. Member District Agriculture. Officer, Champhai District. -

Resutls for Gramin Dak Sevak for North Eastern Circle

Resutls for Gramin Dak Sevak for North Eastern Circle S.No Division HO Name SO Name BO Name Post Name Cate No Registration Selected Candidate gory of Number with Percentage Post s 1 Manipur Imphal H.O Chakpikarong Gobok B.O GDS BPM UR 1 R1DC82FB64C36 SOWNDERYA M S.O (92.8) 2 Manipur Imphal H.O Chakpikarong Sajik Tampak GDS MD UR 1 R018457C4E49D THIYAM INAO S.O B.O SINGH (91.2) 3 Manipur Imphal H.O Chandel S.O Mittong B.O GDS BPM UR 1 R4C18B72F4591 KHUTLEIBAM MD KANOON HAQUE (91.8) 4 Manipur Imphal H.O Churachandp South Kotlein GDS BPM UR 1 R84F8FBA8DA21 PUKHRAMBAM ur S.O B.O VASKAR SINGH (91.2) 5 Manipur Imphal H.O Lamlong S.O Huidrom B.O GDS MD OBC 1 R24756BB59EAD SANGEETH M P (92.8889) 6 Manipur Imphal H.O Lamlong S.O Nongoda B.O GDS BPM SC 1 R1AC74CAF5489 CHINGTHAM LOYALAKPA SINGH (95) 7 Manipur Imphal H.O Litan S.O Semol B.O GDS BPM UR 1 R8723E884ED43 RUHANI ALI (91.2) 8 Manipur Imphal H.O Litan S.O Thawai B.O GDS BPM UR 1 R3A6764E447F4 SHYJIMOL C (94.6) 9 Manipur Imphal H.O Mao S.O Mao S.O GDS MD UR 1 R74DBE3D94C4B MD SARIF (91.2) 10 Manipur Imphal H.O Moreh S.O Bongjoi B.O GDS BPM UR 1 R5DB3F6B4AAF3 MD YAKIR HUSSAIN (91.2) 11 Manipur Imphal H.O Nambol S.O Bungte Chiru GDS BPM UR 1 R52EAF9243942 THOUDAM B.O MICHEAL SINGH (95) 12 Manipur Imphal H.O Nambol S.O Manamayang GDS BPM UR 1 R7AFF761A47A4 KUMAR MANGLAM B.O (93.1) 13 Manipur Imphal H.O Singhat S.O Behiang B.O GDS BPM UR 1 R53B454F6511B RITEZH THOUDAM (95) 14 Manipur Imphal H.O Yairipok S.O Angtha B.O GDS BPM OBC 1 R03184F4ECDC8 KOHILA DEVI G (95) 15 Manipur Imphal H.O Yairipok -

MIZORAM Email: [email protected]

OFFICE OF THE PRINCIPAL INSTITUTE OF ADVANCED STUDIES IN EDUCATION AIZAWL : : MIZORAM www.iasemz.edu.in email: [email protected]. No. 8794002542 Fax: 0389-2310565 PB.No.46 No.J.14011/2/2021-EDC(IASE) Dated 19th July, 2021 LIST OF CANDIDATES ELIGIBLE FOR PERSONAL INTERVIEW (B.ED.) FOR THE ACADEMIC SESSION 2021-2023 Sl. Registered NAME Father’s/Mother’s/Guardian’s Address No. Sl. No. Name 1 2 ABRAHAM C.Thanhranga Electric Veng,Lawngtlai VANLALMALSAWMTLUANGA CHINZAH 2 3 AKASH KUSUM CHAKMA Basak Chandra Chakma Kamalanagar, Chawngte 3 4 ALBERT LALLAWMSANGA R.Lalmuanchhana Kawnveng,Darlawn 4 5 ALICE MALSAWMTHANGI H.Lalngaizuala Chaltlang Lily Veng 5 8 AMAR JYOTI CHAKMA Basak Chandra Chakma Kamalanagar Iv, Chawngte 6 9 AMITA RANI ROY Kartik Roy Raj Bhawan,Aizawl 7 11 ANDREW F LALRINSANGA F.Lalhmingliana Upper Kanan 8 17 ANNETTE MALSAWMZUALI Lalsanglura Phq, Khatla, Aizawl 9 18 ANTHONY SAIDINGPUIA Stephen Lalzirliana Anthony Saidingpuia 10 21 R. VANLALHMUNMAWII R. Lalsawma Hnahthial Bazar Veng 11 28 BABY LALBIAKSANGI T.Lalnunmawia Salem Veng 12 30 BABY LALRUATSANGI R.Laltanpuia Kawnpui 13 31 BARBARA LALRUATDIKI T.Vanlalpara Darlawn 14 34 BEIHNIARILI SYUHLO Bl Syuhlo College Vaih-I, Siaha 15 36 BENJAMIN LALRINAWMA K. Vanlalmuanpuia N. E. Khawdungsei 16 46 BRENDA TLAU Lalchungnunga Ramhlun Vengthlang Aizawl 17 47 BRIGIT RAMENGMAWII Joseph Dawngliana 4/63 A Kulikawn, Aizawl 18 50 C. LALMALSAWMA C. Zohmingthanga Durtlang Mualveng, Aizawl 19 51 C. LALREMRUATA Lalzemawia Dinthar Veng, Serchhip 20 57 C.LALAWMPUII C.Lalnidenga Bungkawn Dam Veng 21 59 C. LALCHHANCHHUAHI C. Rammawia Zohmun 22 61 C LALCHHUANMAWII C Lalhmachhuana H-48zemabawk Zokhawsang Veng 23 62 C. -

SDEO CHAMPHAI Sl

SELECTED CANDIDATES FOR TEMPORARY ENGAGEMENT OF MIDDLE SCHOOL HINDI TEACHERS UNDER CSS WITH PLACE OF POSTING, 2020-2021 UNDER SDEO CHAMPHAI Sl. Name of Name and Address Qualification Remarks Name Of School Place of Posting No Training Hindi General Lalkhawngaihkimi Praveen Hindi Shikshan 1 D/o Nghakliana HSSLC Govt Vangchhia M/S SDEO Champhai (Mizoram) Diploma Khuangthing H/No V-57 Jenny Lalrinmawii Praveen Hindi Shikshan 2 D/o B.Chhuahkhama HSSLC Govt Hmunhmeltha M/S SDEO Champhai (Mizoram) Diploma Hmunhmeltha, Champhai Lynda Zomuanpuii Praveen Hindi Shikshak Govt Middle School,New 3 D/o M.Liana HSSLC SDEO Champhai (Mizoram) Diploma Hruaikawn Bungkawn AW-31(A) C.Zalianpari Praveen 4 D/o C.Lalmuana B.A Parangat Govt Mualkawi M/S SDEO Champhai (Mizoram) Mualkawi,Champhai District Lalhriattiri D/o Kepliana Praveen Hindi Shikshak 5 HSSLC Thekpui UPS SDEO Champhai Farkawn,Theirekawn (Mizoram) Diploma Champhai Dist. Nangkapliana Praveen Hindi Shikshak 6 S/o SB Sawngkhawzama HSSLC Govt. Border M/S, Sesih SDEO Champhai (Mizoram) Diploma Ramhlun South, H/No Y-106 S.Kapkhandova Praveen Hindi Shikshan 7 S/o S.Hauzanang B.A Govt Melbuk M/S SDEO Champhai (Mizoram) Praveen Melbuk, Champhai F.Zodinpuii Praveen Hindi Shikshak 8 D/o Tlangchhana HSSLC Govt Khuangleng M/S SDEO Champhai (Mizoram) Diploma Khuangleng James Lalmalsawma S/o Siamhnuna Praveen Hindi Shikshak 9 HSSLC Presby.Eng.School,Hnahlan SDEO Champhai Durtlang Leitan, Ramthar (Mizoram) Diploma H/No LV/C-74 Vungsailiani Praveen Hindi Shikshak 10 D/o Ngindothanga HSSLC Govt Leisenzo M/S SDEO -

SELESIH 2 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl

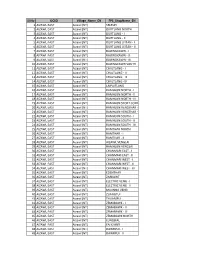

Sl No DCSO Village_Name_EN FPS_ShopName_EN 1 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) SELESIH 2 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) DURTLANG NORTH 3 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) DURTLANG - I 4 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) DURTLANG - II 5 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) DURTLANG LEITAN - I 6 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) DURTLANG LEITAN - II 7 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) BAWNGKAWN - I 8 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) BAWNGKAWN - II 9 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) BAWNGKAWN - III 10 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) BAWNGKAWN SOUTH 11 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) CHALTLANG - I 12 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) CHALTLANG - II 13 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) CHALTLANG - III 14 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) CHALTLANG -IV 15 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) LAIPUITLANG 16 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) RAMHLUN NORTH - I 17 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) RAMHLUN NORTH - II 18 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) RAMHLUN NORTH - III 19 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) RAMHLUN SPORT COMPLEX 20 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) RAMHLUN VENGTHAR - I 21 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) RAMHLUN VENGTHAR - II 22 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) RAMHLUN SOUTH - I 23 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) RAMHLUN SOUTH - II 24 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) RAMHLUN SOUTH - III 25 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) RAMTHAR NORTH 26 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) RAMTHAR - I 27 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) RAMTHAR - II 28 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) AIZAWL VENGLAI 29 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) RAMHLUN VENGLAI 30 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) CHANMARI EAST - I 31 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) CHANMARI EAST - II 32 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) CHANMARI WEST - I 33 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) CHANMARI WEST - II 34 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) CHANMARI WEST - III 35 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) EDENTHAR 36 AIZAWL -

Sc No 105/2013 Crl.Tr.145/2013 U/S 376(I) IPC, Champhai P.S Case No.86/2013

IN THE COURT OF ADDL.DISTRICT & SESSIONS JUDGE-I AIZAWL JUDICIAL DISTRICT, AIZAWL Sc No 105/2013 Crl.Tr.145/2013 U/S 376(i) IPC, Champhai P.S Case No.86/2013 State of Mizoram : Complainant Vrs Lalneihchhunga : Accused. BEFORE Vanlalmawia Addl District & Sessions Judge, Aizawl Judicial District, Aizawl. PRESENT For the Opposite party : R. Lalremruata, Addl. P.P. For the Accused : Lalramhluna, Advocate. Date of Order : 7.3.2017 ORDER The prosecution story of the case in brief is that , on dt.11.6.2013 at 11:50 am, a written report was received from Lalruatmawia S/o Vanlalngura (L) of Vaphai Village, Champhai District to the effect that on 10.6.2013 at around 11:30 am, his sister Lalsangpuii (38) D/o Vanlalngura (L) of Vaphai Village who was mentally retarded was rape by Lalneihchhunga (32) S/o Thanglianchhuma of Vaphai Village inside the house of his younger brother PC Lalnghakliana s/o Vanlalngura(L) of Vaphai Village who was living next door to their house. Hence, CPI PS Case No.86/2013 dt.11.6.2013 u/s 376(1) IPC was registered and duly investigated into. 2. During investigation, the complainant was thoroughly examined and recorded his statement. The PO was visited but no physical clue was found at the Page 1 of 15 PO. The victim Lalsangpuii (38) D/o Vanlalngura (L) of Vaphai Village was forwarded to the Medical Officer, PHC Khawbung for medical examination by observing all legal formalities,. According to the Medical Examination report, the doctor opined that the victim sustained old torn hymen which may be as a result of previous penetration which does not rule out recent penetration. -

Sl.No Name Father's/Mother's/Guardi An's Name Gender Address 1

XI COMMERCE GOVT G.M. HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL, CHAMPHAI MIZORAM Father's/Mother's/Guardi Sl.No Name Gender Address an's Name 1 Agnes Chinghawihchiangi Francis Tuangzachina Female Champhai, Vengthar 2 B Lalpekhlua B Laldinsanga Male Vengsang, Champhai 3 C. Vanlalhmuaki C. Lalbuatsaiha Female Champhai Electric Veng 4 Chinghaumawii Kapliankhupa Female Vengthar, Champhai 5 Emmanuel Lalruatsangi J. Lallawmthanga Female Kanan Veng, Champhai 6 Esther Lalrinpuii Lalremruata Female Champhai, electric 7 F.Vanlalthlamuana Vanlalhriata Male champhai venglai 8 Helen. Thlahleihhniangi R. T. Biakcheuva Female Zokhawthar 9 Hmingthanzauvi Lalropuii Female Vanzau 10 Isak Remruatfela H.C Rohmingmawia Male Vengsang,Champhai 11 JOHAN LALRUATFELA Lalthanzama Male Buang (Kanan Veng, Champhai) 12 K. Malsawmtluangi K. Lalthasanga Female Vengthlang, Champhai 13 K.Laltanpuii Lalhmangaiha Female Khawhai 14 KIM THAWN MANG DAI NGAIH MAN Male KAWNPUI , NGAIZAWL 15 Lalbiakdiki Lalnunmawia kawlni Female Vengthlang North 16 Lalhriatrengi Vanlalkhara Female Zion veng 17 Lalmihriati Manglawma Female Venglai,Champhai 18 Lalnuntluanga Zothanpuii Male Champhai Kahrawt XI COMMERCE 19 Lalnuntluanga Vanlalhnema Male Kanan Veng,Champhai 20 Lalrammuanawma Hrangchuana Male Champhai, Zotlang 21 Lalrinawma Lalthlennghaka Male Champhai Electric 22 Lalrindiki Laltlanzama Female Vengsang Champhai 23 Lalrinmawii Lalengliana Female Champhai,Bethel 24 Lalrinngheti Laltlanmawia Female Champhai kahrawt 25 Lalrinpuii Laldingngheti Female Vengthlang, Champhai 26 Lalrochawia B.Lalbiaklawma Male