Ancient Calendars and Constellations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Babylonian Populations, Servility, and Cuneiform Records

Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 60 (2017) 715-787 brill.com/jesh Babylonian Populations, Servility, and Cuneiform Records Jonathan S. Tenney Cornell University [email protected] Abstract To date, servility and servile systems in Babylonia have been explored with the tradi- tional lexical approach of Assyriology. If one examines servility as an aggregate phe- nomenon, these subjects can be investigated on a much larger scale with quantitative approaches. Using servile populations as a point of departure, this paper applies both quantitative and qualitative methods to explore Babylonian population dynamics in general; especially morbidity, mortality, and ages at which Babylonians experienced important life events. As such, it can be added to the handful of publications that have sought basic demographic data in the cuneiform record, and therefore has value to those scholars who are also interested in migration and settlement. It suggests that the origins of servile systems in Babylonia can be explained with the Nieboer-Domar hy- pothesis, which proposes that large-scale systems of bondage will arise in regions with * This was written in honor, thanks, and recognition of McGuire Gibson’s efforts to impart a sense of the influence of aggregate population behavior on Mesopotamian development, notably in his 1973 article “Population Shift and the Rise of Mesopotamian Civilization”. As an Assyriology student who was searching texts for answers to similar questions, I have occasionally found myself in uncharted waters. Mac’s encouragement helped me get past my discomfort, find the data, and put words on the page. The necessity of assembling Mesopotamian “demographic” measures was something made clear to me by the M.A.S.S. -

Chapter 6: India

Chapter 6: India Subhash Kak Our understanding of archaeoastronomical sites in India is based not only on a rich archaeological record and texts that go back thousands of years, but also on a living tradition that is connected to the past. Conversely, India has much cultural diversity and a tangled history of interactions with neighbouring regions that make the story complex. The texts reveal to us the cosmological ideas that lay behind astronomical sites in the historical period and it is generally accepted that the same ideas also apply as far back as the Harappan era of the third millennium BC. In the historical period, astronomical observatories were part of temple complexes where the king was consecrated. Such consecration served to confirm the king as the foremost devotee of the chosen deity, who was taken to be the embodiment of time and the universe. For example, Udayagiri, located a few km from Vidisha in central India, is an astronomical site connected with the Classical age of the Gupta dynasty (320–500 AD). The imperial Guptas enlarged the site, an ancient hilly observatory going back at least to the 2nd century BC, at which observations were facilitated by the geographical features of the hill, into a sacred landscape to represent royal authority. Indian astronomy is characterised by the concept of ages of successively longer durations, which is itself an instance of the pervasive general idea of recursion, or repetition of patterns across space, scale and time. An example of this is the division of the ecliptic into 27 star segments ( nakshatras ), with which the moon is conjoined in its monthly circuit; each of these segments is further divided into 27 sub-segments ( upa-nakshatras ), and the successive divisions of the day into smaller measures of 30 units. -

The Calendars of India

The Calendars of India By Vinod K. Mishra, Ph.D. 1 Preface. 4 1. Introduction 5 2. Basic Astronomy behind the Calendars 8 2.1 Different Kinds of Days 8 2.2 Different Kinds of Months 9 2.2.1 Synodic Month 9 2.2.2 Sidereal Month 11 2.2.3 Anomalistic Month 12 2.2.4 Draconic Month 13 2.2.5 Tropical Month 15 2.2.6 Other Lunar Periodicities 15 2.3 Different Kinds of Years 16 2.3.1 Lunar Year 17 2.3.2 Tropical Year 18 2.3.3 Siderial Year 19 2.3.4 Anomalistic Year 19 2.4 Precession of Equinoxes 19 2.5 Nutation 21 2.6 Planetary Motions 22 3. Types of Calendars 22 3.1 Lunar Calendar: Structure 23 3.2 Lunar Calendar: Example 24 3.3 Solar Calendar: Structure 26 3.4 Solar Calendar: Examples 27 3.4.1 Julian Calendar 27 3.4.2 Gregorian Calendar 28 3.4.3 Pre-Islamic Egyptian Calendar 30 3.4.4 Iranian Calendar 31 3.5 Lunisolar calendars: Structure 32 3.5.1 Method of Cycles 32 3.5.2 Improvements over Metonic Cycle 34 3.5.3 A Mathematical Model for Intercalation 34 3.5.3 Intercalation in India 35 3.6 Lunisolar Calendars: Examples 36 3.6.1 Chinese Lunisolar Year 36 3.6.2 Pre-Christian Greek Lunisolar Year 37 3.6.3 Jewish Lunisolar Year 38 3.7 Non-Astronomical Calendars 38 4. Indian Calendars 42 4.1 Traditional (Siderial Solar) 42 4.2 National Reformed (Tropical Solar) 49 4.3 The Nānakshāhī Calendar (Tropical Solar) 51 4.5 Traditional Lunisolar Year 52 4.5 Traditional Lunisolar Year (vaisnava) 58 5. -

The Indian Luni-Solar Calendar and the Concept of Adhik-Maas

Volume -3, Issue-3, July 2013 The Indian Luni-Solar Calendar and the giving rise to alternative periods of light and darkness. All human and animal life has evolved accordingly, Concept of Adhik-Maas (Extra-Month) keeping awake during the day-light but sleeping through the dark nights. Even plants follow a daily rhythm. Of Introduction: course some crafty beings have turned nocturnal to take The Hindu calendar is basically a lunar calendar and is advantage of the darkness, e.g., the beasts of prey, blood– based on the cycles of the Moon. In a purely lunar sucker mosquitoes, thieves and burglars, and of course calendar - like the Islamic calendar - months move astronomers. forward by about 11 days every solar year. But the Hindu calendar, which is actually luni-solar, tries to fit together The next natural clock in terms of importance is the the cycle of lunar months and the solar year in a single revolution of the Earth around the Sun. Early humans framework, by adding adhik-maas every 2-3 years. The noticed that over a certain period of time, the seasons concept of Adhik-Maas is unique to the traditional Hindu changed, following a fixed pattern. Near the tropics - for lunar calendars. For example, in 2012 calendar, there instance, over most of India - the hot summer gives way were 13 months with an Adhik-Maas falling between to rain, which in turn is followed by a cool winter. th th August 18 and September 16 . Further away from the equator, there were four distinct seasons - spring, summer, autumn, winter. -

Calendar 2020

MARCH 2020 Phalguna 2076 - Chaitra 2077 Shukla Paksha Shashthi Shukla Paksha Chaturdashi Krishna Paksha Saptami Krishna Paksha Trayodashi Shukla Paksha Panchami Festivals, Vrats & Holidays Phalguna Phalguna Chaitra Chaitra Chaitra 3 Holashtak १ ८ १५ २२ २९ Sun 1 21 8 29 15 7 22 13 29 20 Masik Durgashtami, Rohini Vrat Krittika Ashlesha Anuradha Shatabhisha 20, Chaitra 6 Amalaki Ekadashi रव. Mesha Kumbha Karka Kumbha Vrishchika Meena Kumbha Meena Vrishabha Meena Narasimha Dwadashi Shukla Paksha Saptami Purnima, Chhoti Holi Krishna Paksha Ashtami Krishna Paksha Chaturdashi Shukla Paksha Shashthi 7 Pradosh Vrat, Shani Trayodashi Phalguna Phalguna Chaitra Chaitra Chaitra 8 Birthday Of Hazrat Ali २ ९ १६ २३ ३० MON 2 22 9 30 16 8 23 14 30 21 International Women's Day Krittika Purva Phalguni Jyeshtha Purva Bhadrapada Rohini 9 Chhoti Holi, Holika Dahan सोम. Vrishabha Kumbha Simha Kumbha Vrishchika Meena Kumbha Meena Vrishabha Meena Vasanta Purnima, Dol Purnima, Shukla Paksha Ashtami Krishna Paksha Pratipada Krishna Paksha Navami Amavasya Shukla Paksha Saptami Phalguna Purnima, Chaitanya Phalguna Chaitra Chaitra Chaitra Mahaprabhu Jayanti, ३ १० १७ २४ ३१ TUE 3 23 10 17 9 24 15 31 22 10 HOLI Rohini Uttara Phalguni Mula Uttara Bhadrapada Mrigashirsha 11 Bhai Dooj, Bhratri Dwitiya मंगल. Vrishabha Kumbha Kanya Kumbha Dhanu Meena Meena Meena Mithuna Meena 12 Shivaji Jayanti, Bhalachandra Shukla Paksha Navami Bhai Dooj Krishna Paksha Dashmi Chaitra Navratri Subh Muhurat Sankashti Chaturthi Phalguna Chaitra Chaitra Starts Marriage: 2, 3, 4, 8, 13 Rang Panchami ४ ११ १८ २५ WED 4 24 11 2 18 10 25 16 11, 12 14 Meena Sankranti Mrigashirsha Hasta Purva Ashadha Revati 15 Sheetala Saptami, World बुध. -

Hindu Calendar Banaras up India

2017 Hindu Calendar Based on Longitude Latitudes of Banaras UP India (For use in UP, Bihar, Punjab, Hariyana Kashmir, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh Delhi, Uttarakhand, Jharkhand) HINDU CALENDRIC SYSTEM IMPORTANT THINGS TO REMEMBER LUNAR MONTH NAMES DAY BEGINS AT SUNRISE NOT MIDNIGHT CHITRA, VAISHAKHA, JYESHTHA, ASHAADH, SHRVANA, BHADRAPADA, AASHVAYUJA (ASHWIN), KARTIKA, MONTH SYSTEMS MARGASIRA, PAUSHA (PUSHYA), MAGHA, PHALGUNA o LUNAR AND SOLAR MONTHS o DIFFERENT SYSTEMS IN DIFFERENT PARTS OF INDIA THITHI (PHASES OF MOON) LUNAR MONTH SYSTEMS (CHANDRAMANA) EACH LUNAR MONTH HAS TWO HALVES – SHUKLA PAKSHA (WAXING MOON), KRISHNA PAKSHA (WANNING MOON). EACH PAKSHA HAS 15 TITHIS. THITHIS IN SHUKLA PAKSHA END WITH PURNIMA (FULL MOON) AND AMAVASYANT MONTH SYSTEM THITHIS IN KRISHNA PAKSHA END WITH AMAVASYA (NEW MOON) HASES OF OONS LIKE ULL MOON ALF MOON EW OON AND OTHERS OCCUR DUE TO THE MONTHS ENDS ON AMAVASYA P M F - , H - , N -M MOON’S POSITION IN ORBIT AROUND THE EARTH. MONTHS BEGIN WITH SHUKLA PAKSHA EACH PHASE IS TITHI. MONTHS ENDS WITH KRISHNA PAKSHA THE LENGTH OF EACH TITHI IS 12 DEGREES POPULAR IN: o MAHARASTRA (SHALIWAHAN ERA) LENGTH OF TITHI CAN RANGE FROM 19 TO 26 HOURS. o GUJARAT (VIKRAM ERA) TITHIS DON’T HAVE A FIX STARTING AND ENDING TIME. o KARNATAKA (SHALIWAHAN ERA) THEY END AT THE SAME INSTANCE ALL OVER THE WORLD. o ANDHRA PRADESH (SHALIWAHAN ERA) THITHI NAMES o PRATIPADA (PRATHAMA), DWITIYA (VIDIYA), TRITIYA (TADIYA), CHATURTHI (CHAVITHI), PURNIMANT MONTH SYSTEM PANCHAMI, SHASTHI, SAPTAMI, ASHTAMI, NAVAMI, DASHAMI, -

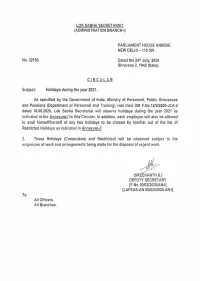

Circular No. 32155

LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT . (ADMINISTRATION BRANCH-I) PARLIAMENT HOUSE ANNEXE NEW DELHl-110 001. No.32155 Dated the 24th July, 2020 Shravana 2, 1942 (Saka). CIRCULAR Subject: Holidays during the year 2021. As specified by the Government of India; Ministry of Personnel, Public .Grievances and Pensions (Department of Personnel and Training) vide their OM F.No .. 12/9/2020-JC:A-2 dated 10.06.2020, Lok Sabha Secretariat will observe holidays during the year 2021 as indicated in the Annexure-1 to this Circular. In addition, each employee will also be allowed to avail himself/herself of any two holidays to be chosen by him/her out of the list of Restricted Holidays as indicated in Annexure-11. 2. These Holidays (Compulsory and Restricted) will be observed subject to the exigencies of work and arrangements being made for the disposal of urgent work. ~ (SREEKANTH S.) DEPUTY SECRET ARY [F .No.10/02/2020/AN-1] [LAFEAS-AN 1020/2/2020-AN··I] To All Officers. All Branches. \, -(2)- ANNEXURE-1 LIST OF HOLIDAYS DURING THE YEAR 2021 FOR ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICES OF CENTRAL GOVERNMENT LOCATED AT DELHI / NEW DELHI S.No. Holiday Date Saka Date Day 1942 SAKA ERA 1. Republic Day January 26 Magha 06 Tuesday 2. Holi March 29 Chaitra 08 Monday 1943 Saka Era 3. Good Friday April 02 Chaitra 12 Friday 4. Ram Navami April 21 Vaisakha 01 Wednesday 5. Mahavir Jayanti ~pril 25 Vaisakha 05 Sunday 6. d-ul-Fitr May 14 Vaisakha 24 Friday 7. Budha Pumima May 26 Jyaishtha 05 Wednesday 8. d-ul-Zuha (Bakrid) lluly 21 Ashadha 30 Wednesday 9. -

Discoveries at Nineveh by Austen Henry Layard, Esq., D.C.L

Discoveries At Nineveh Discoveries At Nineveh by Austen Henry Layard, Esq., D.C.L. ¡ ¢ £ ¤ ¥ ¦ § ¨ ¨ ¢ ¤ © ¢ ¨ ¢ § ¦ © . Austen Henry Layard. J. C. Derby. New York. 1854. Assyrian International News Agency Books Online www.aina.org 1 Discoveries At Nineveh Contents PREFACE TO THE ABRIDGMENT .................................................................................................................... 3 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Chapter 1................................................................................................................................................................. 8 Chapter 2............................................................................................................................................................... 13 Chapter 3............................................................................................................................................................... 23 Chapter 4............................................................................................................................................................... 32 Chapter 5............................................................................................................................................................... 40 Chapter 6.............................................................................................................................................................. -

Temple Timings Saturday and Sunday Monday

Temple Timings Saturday and Sunday 9:00 am - 8:30 pm Monday - Friday 9:30 am - 12:30 pm 5:30 pm - 8:30 pm Temple Priest Sankaramanchi Nagendra Prasad (Sharmaji) was born in 1967 East Godavari District, India. His ancestors from thirteen generations were members of the priest class and for centuries had been in charge of the temple in their village Tapeshwaram. At the age of 9, Sharmaji entered the priesthood, as had many previous family members from Amaravati. He graduated from Sri Venkateshwara Vedic School, Tirupathi and came to US in 1994 to Aurora Temple, Chicago. In 1997, he was asked by Datta Yoga Center through Ganapathi Sachidanda Swa. miji's blessings to accept a position as Head Priest in Datta Temple, Baton Rouge, LA. He continued his career in Datta Temple as a registered Hindu priest with East Baton Rouge Clerk of Court. In august 2007, he got relieved from his responsibilities as Head priest from Datta Temple. During this time he performed many pujas in temple and with devotees all around the nation for many festivals and special occasions. Beginning August 2007, he independently started performing all religious ceremonies as a step towards building his personal service to the community. He started his first religious service with Lord Ganesh Puja on Vinayaka Chavithi on 09/15/2007 with all the support from devotees and friends. We expect full support and encouragement from all the devotees in his future developments just as much in the past. Being true believers of ancestors and pious culture with utmost admiration and whole hearted dedication, Sharmaji is participating in propagating the Vedic culture for all devotees. -

(2008) a Bibliography of Neo-Assyrian Studies

State Archives of Assyria Bulletin Volume XVII (2008) A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF NEO-ASSYRIAN STUDIES (1998–2006) Mikko Luukko – Salvatore Gaspa Introductory notes In a way, this bibliography is a continuation of the previous bibliographies compiled by Hämeen-Anttila 1 and Mattila – Radner. 2 The difference between Hämeen-Anttila’s bibliography and the present one, however, is that we have tried to provide both the pro- fessional Assyriologist and the student of Assyriology with a considerable selection of secondary literature too. Therefore, this bibliography does not only list Neo-Assyrian text editions or studies that almost exclusively deal with the various linguistic aspects of Neo-Assyrian. One of the main reasons for this decision is simply the fact that during the last ten-twenty years the Neo-Assyrian data have often been approached in an inter- disciplinary way. Hence, without listing titles belonging to relevant secondary literature, the viewpoint on Neo-Assyrian studies would remain unsatisfactory. Moreover, one could even maintain that during the last ten years, at the latest, the focus of Neo-Assyr- ian studies has somewhat shifted from its traditional philological roots to more interdis- ciplinary studies, at least quantitatively. Doubtless, this shift has affected the applied methods and methodologies in an unprecedented way. Nevertheless, many readers may still be puzzled when seeing titles listed here that refer to biblical, Aramaic, Greek, Median, Neo-Babylonian, Neo-Elamite, Phoenician and Urar\ian topics, but do not mention Neo-Assyrian at all. This results from an attempt to see Neo-Assyrian studies as part of a bigger picture. * We would like to thank G.B. -

Assyrian Imperial Administration 680-627 BCE : a Comparison Between Babylonia and the West Under Esarhaddon and Assurbanipal

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses : Honours Theses 2007 Assyrian Imperial Administration 680-627 BCE : A Comparison Between Babylonia and the West Under Esarhaddon and Assurbanipal Ivan Losada-Rodriguez Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons Part of the Islamic World and Near East History Commons Recommended Citation Losada-Rodriguez, I. (2007). Assyrian Imperial Administration 680-627 BCE : A Comparison Between Babylonia and the West Under Esarhaddon and Assurbanipal. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/1398 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/1398 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. ASSYRIAN IMPERIAL ADMINISTRATION 680-627 BCE A Comparison Between Babylonia and the West Under Esarhaddon and Assurbanipal By Ivan Losada-Rodriguez A dissertation submitted as partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts (History) - Honours Edith Cowan University International, Cultural and Community Studies Faculty of Education and Arts Date of Submission: 12 November 2007 USE OF THESIS The Use of Thesis statement is not included in this version of the thesis. -

Proquest Dissertations

The sun, moon and stars of the southern Levant at Gezer and Megiddo: Cultural astronomy in Chalcolithic/Early and Middle Bronze Ages Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Gardner, Sara Lee Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 23:39:58 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/280233 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. ProQuest Information and Leaming 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 THE SL'N.